Exploring My Identity

Explore the complexities of our own identities, and how these identities shape the way we view and act in the world.

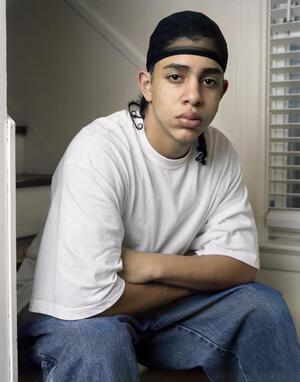

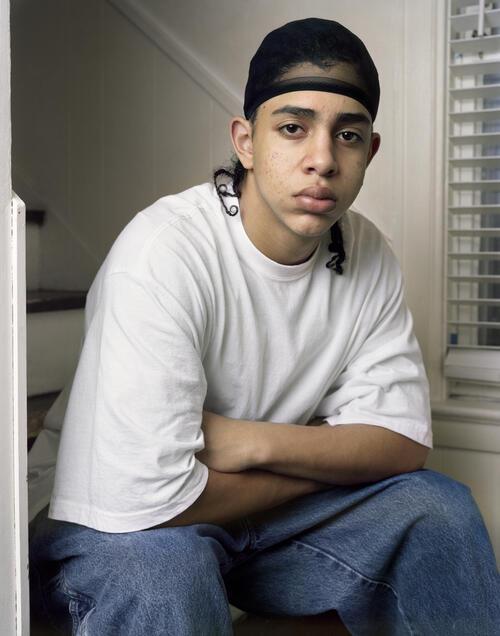

Jacob, by Dawoud Bey, 2005. Pigment Print, with interview by Dan Collison and Elizabeth Meister.

Courtesy of Dawoud Bey. Commissioned by the Jewish Museum for the exhibition The Jewish Identity Project: New American Photography.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- Our identities are complex and shifting, and shape the way we move through the world.

- Jewish identity is not simple and homogenous, but complex and changing.

Essential Questions

- What are the parts of your identity?

- What are the factors that influence our own identities (those identities that we choose and those that are imposed on us by others)?

- How does your identity change, or how might parts of your identity come into conflict, in different contexts?

- What stereotypes do we have about Jews in America?

Materials Required

- 3 x 5 or 4 x 6 index cards (some colored)

- Unlined white paper

- Copies of one of the document studies

Notes to Teacher

This lesson explores issues of identity, race, and Jewishness. Therefore, the documents intentionally focus on the experiences of Jews who are not white. There are many other facets of Jewish identity worthy of exploration which are not addressed directly in this lesson.

Prior to class, review the introductory essay and the four different Document Studies. Choose one Document Study to use with your class, based on which you think will lead to the most productive conversation. The discussion questions for each document can be found in each Document Study. Alternatively, you can divide your class into four groups and have each group focus on a different document and then come back together to share and discuss larger themes. (The directions in Part II of this lesson are for using one document with the whole class, but can be easily adapted.)

The "Defining My Identity" index card activity can be done before or after the Document Study. It is designed to introduce concepts of identity to students who have not yet engaged in identity exploring activities; if your students have already done identity exploration work, you may want to skip this activity entirely.

American Jews, Race, Identity, and the Civil Rights Movement

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy Unit 1, Lessons 1-4

In every generation, people shape their sense of themselves and their place in society within the frameworks defined by their local community and the larger national community. What does it mean to be white? What constitutes Jewishness? (Is it a race? An ethnicity? A religion? A nationality?) The answers to these questions are not fixed but rather are constantly shifting, especially in a modern context in which people have multiple, sometimes competing, identities.

Race may, at first glance, seem to be the most immutable identity – existing "in the blood" or written on one's skin – but it is actually fluid. Before the mid-19th century, European immigrants to the United States were mostly absorbed into the white population, and Jews – though considered religiously "other" and often socially separate – were not viewed in racial terms. But the rise of mass immigration from Europe, beginning in the 1840s, brought in a new wave of immigrants too large to be easily assimilated, and this new social reality of large urban populations with a heavy European immigrant flavor led to a recasting of racial categories and relations. The ruling elite classes (predominantly wealthy, American-born Protestants) expressed their fears of "race suicide" as the "native" stock was infiltrated and overrun by these "inferior races" first from Ireland and then from Eastern and Southern Europe. This immigration wave brought nearly 2 million Jews to the United States, outnumbering the German Jewish elite who had arrived in the mid-19th century and transforming the American Jewish community, which had been predominantly Sephardic (of Spanish/Portuguese origin), into a predominantly Ashkenazi population, as it remains today.

The new racism that arose in response to the immigration wave was rooted in supposed science – intelligence tests and a eugenics movement that focused on breeding "better" people, as opposed to the "feebleminded" Eastern Europeans, Mexicans, Asians, Native Americans, and African Americans. This "scientific racism" justified the passage of legislation that outlawed Chinese immigration (Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882) and heavily restricted immigration except from Northern Europe (Johnson Act of 1924). The government and businesses limited the social mobility of those "inferior races" who had already settled in the US through policies such as quotas in higher education, corporate hiring restrictions, and, in the postwar period, federal housing loan policies that enforced racial segregation and subsidized the suburbanization of white populations.

In this context of changing perceptions of race, the racial identification of Jews underwent significant shifts. On one level, most Jews were always considered white in that they were permitted to become naturalized citizens – a right reserved only for "free white persons," according to the 1790 law set in place by the first Congress. But during the years of the large wave of immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe (roughly 1880-1924), Jews were counted among the many European groups (the 1911 Dillingham Commission Report on Immigration identified 36 different European races) classified as not quite white, or racially "other." (Some Jews, for example, were classified as "Hebrew.") Who fell into this racially suspect category depended on who was seen as different, unassimilable, or a threat to the nation, as well as who was perceived as providing essential (though devalued) labor. In the 1860s, the Irish were singled out for their savagery and racial weakness; by the end of the 19th century, Jews often bore the brunt of anti-immigration racism, targeted as the racial scourge overrunning and infecting urban areas. Political cartoons, for example, often depicted Jews as dirty, diseased, and criminal. Though expressed in racial terms, this anti-immigrant sentiment also intersected with fears of the rising working class and of political radicalism.

This racial definition of Jewishness, though derogatory when applied by non-Jews, could also serve a positive purpose for Jews. Many Jews embraced race as something that united them – a kind of identity deeper than belief or religious practice, something primal, defying assimilation. Racial identification resonated with a Jewish sense of peoplehood – an identification that was not entirely captured by the definition of Jewishness as solely a religious identity – and fulfilled the desire to preserve a minority identity.

Soon after the Johnson Act effectively closed the door on immigration from anywhere but Northern Europe, conventional wisdom on racial classification moved toward the recognition of three main races: Caucasian, Mongoloid, and Negroid. This meant that the many different European races – including Jews – were consolidated into a monolithic category of Caucasian whiteness, and the primary racial distinction in America became the black/white binary.

Several factors led to this consolidation of whiteness. In light of the severe immigration restriction, those formerly considered "racially other" now posed less of a threat. Without a steady stream of new immigrants, the Eastern and Southern European populations were now predominantly American born, not immigrants themselves, and thus seemed less different and more easily assimilable. At the same time, the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to urban North and West between 1910s and 1940s threw the distinction between black and white into sharper relief.

The involvement of African Americans in World War II also caused a major shift in racial issues on the home front. The dissonance African Americans experienced between fighting for democracy abroad but being denied its benefits at home led to a surge in civil rights activism, particularly around segregation of the armed forces and the defense industries. As segregation (also known as "Jim Crow") became the central American racial issue, racial differences among whites became less important. By emphasizing the black/white binary, Jim Crow could work to solidfy the whiteness of certain groups, such as Jews, who had previously been considered ambiguously white. Finally, Nazi Germany served as a sharp reminder of the horrific dangers of race-based classifications.

After World War II, Jewishness remained a social distinction but no longer a racial one. For example, Jews were allowed to move into white suburban neighborhoods that the Federal Housing Authority policy determined were only for people of the "same social and racial classes" (though some communities instituted housing covenants that excluded Jews). "Ethnicity" became the new language to describe difference among whites, now seen as cultural – a distinction that further entrenched the black/white divide by implying that racial differences go deeper than cultural differences. The new racial system defined whiteness as the "normal" American state, and blackness as a racial problem.

Many scholars have argued that Jews in the South were the first Jews to see themselves as white, but the case of Leo Frank makes clear that they occupied an ambiguous middle category of racial outsider. In April 1913, a 14-year-old white girl was murdered in a pencil factory in Atlanta, and Leo Frank, a Jewish part-owner and manager of the factory, was convicted of the crime based on the testimony of a black janitor. When his sentence was commuted by the Governor in August 1915, a mob pulled him out of the prison where he was being held and lynched him. That a supposedly white man could be convicted based on the testimony of a black man, and the use of lynching as the method of (illegally) meting out his punishment, demonstrates the contingency of Frank's perceived whiteness.

Throughout the postwar period, the social position of Jews in the South was precarious, despite the fact that Southern Jews were among those Jews with the longest roots in the US. Jews in the South were accepted as part of the social fabric, and in many cities were prominent business people who often ran the local store, but they were also seen as different from other whites and somewhat suspect, and in some cases excluded along with blacks. They had to work hard to fit in, and many Jews were reluctant to take action that would set them apart from the other white community leaders. They felt they needed to assure their own equality and security first, and therefore were often hesitant to engage in overt, public civil rights activism, though some supported civil rights in quiet, private ways.

While for some Southern Jews, association with the Civil Rights Movement confirmed for their white neighbors a lingering sense that Jews were racially tainted, for many Northern Jews, involvement in the Civil Rights Movement served to further solidify Jewish whiteness. Allying themselves with blacks cast into sharper relief the whiteness of Jews – ironically, since many Jews were motivated to civil rights activism by a sense of identification with African Americans and a persistent sense of "otherness" despite having, by and large, "made it" in America.

Today, many American Jews retain an ambivalence about whiteness, despite the fact that the vast majority have benefited and continue to benefit from white privilege. This ambivalence stems from many different places: a deep connection to a Jewish history of discrimination and otherness; a moral imperative to identify with the stranger; an anti-universalist impulse that does not want Jews to be among the "melted" in the proverbial melting pot; an experience of prejudice and awareness of the contingency of whiteness; a feeling that Jewish identity is not fully described by religion but has some ethnic/tribal component that feels more accurately described by race; and a discomfort with contemporary Jewish power and privilege.

And of course, while there is a tendency in the US, where the majority of Jews are of Eastern European descent, to assume a shared white racial identity for Jews, many Jews are in fact not white. Throughout history, Jews have come in all colors and from all places, and have almost always lived multicultural lives. The "mixed multitude" of the Jewish people include Jews from Arab lands (Mizrahi Jews), Jews with roots in Spain and Portugal (Sephardic Jews), and Jews from India, Asia, and Africa, some of whose ancestors may have been separated from the rest of the Jewish community many centuries ago. There are many Jews of color whose families have been Jewish for generations, if not centuries. In an American context that increasingly values diversity, the backgrounds and colors of the Jewish community are also enriched by adoption, intermarriage, and conversion. The Institute for Jewish and Community Research, an organization that studies the demography of the Jewish people, estimates that at least 20% of the American Jewish population is what they term "racially and ethnically diverse, including African, African American, Latino (Hispanic), Asian, Native American, Sephardic, Mizrahi and mixed-race Jews by heritage, adoption, and marriage."

Just as the definition of racial categories in America is always shifting, as illustrated by changes in the options for racial self-definition on the US Census, so, too, does the definition of Jewish identity and the image of what Jewish looks like continue to change.

Defining My Identity

- Hand out one colored index card to each student. Ask your students:

- If I were to ask you right now "Who are you?" what are the first five things that would come into your head? "I am a…." Write these five things down on your index card.

- Explain to your students: Today we’ll be talking about identity, a term that’s often thrown around without much exploration. The exercise we just did on the index cards is meant to help us think more concretely about the concept of identity by naming some aspects of our own lives by which we define ourselves. The five things we each listed on our cards represent facets of our identities and should help us understand that our identities are complex and change over time and in different contexts.

- Have each student find someone else in the class with which they share at least one thing in common from their list. Give each pair a piece of white paper and have the students draw a Venn diagram of their identity lists showing in what ways their identities are similar (overlap) and in what ways they are different. Once the diagrams are drawn have your students discuss whether there are things from the other person's list that they would have added to their list if they could have written down more than five things? Write these items next to the Venn diagram.

- Have your students come back together as a class and ask a few of the groups to share their Venn diagrams. Ask your class:

- What about the similarities and/or differences we found in each other's identities surprised you?

- Think to yourself: what things came to mind that you chose not to include in your list or Venn diagram?

- Ask your students to return to their index card and think about which things they would remove or add if they were filling it out in a different setting: at their school; while doing their favorite activity or hobby; while in their own neighborhood; at synagogue; at camp.

- When all of your students have had a chance to write down their new identity list, ask the following questions:

- What things remained the same when you revised your list?

- What did you delete or add when you revised your list?

- If your lists are different, why do you think this is?

- How do you think a setting/group of people might change the way you think about your identity?

- How do you think a setting/group of people might change the way you choose to present your identity? (i.e. are there times that you would choose to wear or not wear a piece of jewelry with a Jewish star? What other examples can you think of with other aspects of your identity?)

- What assumptions do people make about you – accurately or inaccurately? What parts of your identity do most people "see" from looking at or speaking with you?

- Which parts of your identity are only "visible" if you choose to express them?

- What do you think this means about our identities?

- Remind students to consider again:

- What did you think of, but choose not to say aloud?

- If you are teaching Unit 1, Lesson 2, collect your students' index cards and Venn Diagrams and keep them to be used for the beginning of that lesson.

Document Study

- Hand out the Document Study you chose for your class.

- As a class, discuss the first set of questions that precede the chosen article or portrait. (Discuss these questions before reading any of the text. The discussion will be based on the title of the article or on visual analysis of the photograph.) You may want to list your students' assumptions about this individual on a chalk board, white board, or chart paper at the front of the class so that they can be referred to later in this activity.

- Have a couple of students read aloud the text (article or transcript) featured in the Document Study.

- As a class, discuss the second set of questions (which follow the article or transcript). Try to draw out from the discussion the following main themes: how the person feels about his/her identity, are any parts of his/her identity in conflict and why, to what degree does s/he have a choice about his/her identity, and do other people see him/her the way s/he sees herself. Give your students as many opportunities as possible to also reflect on their own experiences related to identity.

Conclusion

Reiterate to your students some of the following ideas:

- Just because we are all Jews doesn't mean we are all identical or all value the same things.

- Like all of you and [name of the person whose document you studied], Jewish people have always had and will continue to have complex identities.

- Some parts of Jews' identities have been chosen, and some parts of their identities have been imposed by others. (You may want to give some examples here taken from individuals your class has already studied during the year.)

- Whether chosen by them or given by others, these identities have affected how Jews—and all people—have seen themselves and how they've acted in the world around them.

My Personal Story: Kimchee on the Seder Plate

Discussion Questions (Part 1) - Before Reading

- How does the image this title conjures up fit with your idea of a Passover seder? How is it similar or different?

- What might be some reasons to have kimchee on a seder plate?

- What assumptions might someone make about the author of this article just based on her name and the title of the article?

My Personal Story: Kimchee on the Seder Plate

One year my mother put kimchee, a spicy, pickled cabbage condiment, on our seder plate. My Korean mother thought it was a reasonable substitution since both kimchee and horseradish elicit a similar sting in the mouth, the same clearing of the nostrils. She also liked kimchee on gefilte fish and matza. “Kimchee just like maror, but better,” she said. I resigned myself to the fact that we were never going to be a “normal” Jewish family.

I grew up part of the “mixed multitude” of our people: an Ashkenazi, Reform Jewish father, a Korean Buddhist mother. I was born in Seoul and moved to Tacoma, Washington, at the age of five. Growing up, I knew my family was atypical, yet we were made to feel quite at home in our synagogue and community. My Jewish education began in my synagogue preschool, extended through cantorial and rabbinical school at Hebrew Union College (HUC), and continues today. I was the first Asian American to graduate from the rabbinical program at HUC, but definitely not the last--a Chinese American rabbi graduated the very next year, and I am sure others will follow.

As a child, I believed that my sister and I were the “only ones” in the Jewish community--the only ones with Asian faces, the only ones whose family trees didn’t have roots in Eastern Europe, the only ones with kimchee on the seder plate. But as I grew older, I began to see myself reflected in the Jewish community. I was the only multiracial Jew at my Jewish summer camp in 1985; when I was a song-leader a decade later, there were a dozen. I have met hundreds of people in multiracial Jewish families in the Northeast through the Multiracial Jewish Network. Social scientist Gary Tobin numbers interracial Jewish families in the hundreds of thousands in North America.

As I learned more about Jewish history and culture, I found it very powerful to learn that being of mixed race in the Jewish community was not just a modern phenomenon. We were a mixed multitude when we left Egypt and entered Israel, and the Hebrews continued to acquire different cultures and races throughout our Diaspora history. Walking through the streets of modern-day Israel, one sees the multicolored faces of Ethiopian, Russian, Yemenite, Iraqi, Moroccan, Polish, and countless other races of Jews--many facial particularities, but all Jewish. Yet, if you were to ask the typical secular Israeli on the street what it meant to be Jewish, she might respond, “It's not religious so much, it's my culture, my ethnicity.” If Judaism is about culture, what then does it mean to be Jewish when Jews come from so many different cultures and ethnic backgrounds?

As the child of a non-Jewish mother, a mother who carried her own distinct ethnic and cultural traditions, I came to believe that I could never be “fully Jewish” since I could never be “purely” Jewish. I was reminded of this daily: when fielding the many comments like, “Funny, you don’t look Jewish,” or having to answer questions on my halakhic status as a Jew. My internal questions of authenticity loomed over my Jewish identity throughout my adolescence into early adulthood, as I sought to integrate my Jewish, Korean, and secular American identities.

It was only in a period of crisis, one college summer while living in Israel, that I fully understood what my Jewish identity meant to me. After a painful summer of feeling marginalized and invisible in Israel, I called my mother to declare that I no longer wanted to be a Jew. I did not look Jewish, I did not carry a Jewish name, and I no longer wanted the heavy burden of having to explain and prove myself every time I entered a new Jewish community. She simply responded by saying, “Is that possible?” It was only at that moment that I realized I could no sooner stop being a Jew than I could stop being Korean, or female, or me. I decided then to have a giyur (conversion ceremony), what I termed a reaffirmation ceremony in which I dipped in the mikvah and reaffirmed my Jewish legacy. I have come to understand that anyone who has seriously considered her Jewish identity struggles with the many competing identities that the name “Jew” signifies.

What does it mean to be a “normal” Jewish family today? As we learn each other’s stories we hear the challenges and joys of reconciling our sometimes competing identities of being Jewish while also feminist, Arab, gay, African-American, or Korean. We were a mixed multitude in ancient times, and we still are. May we continue to see the many faces of Israel as a gift that enriches our people.

Discussion Questions (Part 2) - After Reading

- If Angela Warnick Buchdahl were to do the 5 part identity activity we did earlier, how might she have filled out her card?

- What made Angela uncomfortable with her identity?

- Has there ever been a situation in which your identity has made you uncomfortable or the actions of others have caused you to question some part of your identity?

- Do you agree or disagree with Angela's mother? Is it possible to change your identity? Why or why not?

- Angela Warnick Buchdahl describes a changing Jewish community. Do you think if she were a child today she would be more comfortable with her identity? What role do you think community plays in identity?

- Angela mentions the "many competing identities that the name 'Jew' signifies." What do you think some of these identities might be? Do you struggle with any of them?

- Revisit the assumptions made about Angela Warnick Buchdahl and her article before you read it. How many of the assumptions were correct? How many were inaccurate? To what degree do we judge someone else's identity by visual clues and/or names?

Ashkenazi Eyes

Discussion Questions (Part 1) - Before Reading

- What kind of image does this title conjure up? What do you think "Ashkenazi eyes" look like? Do you think this description is positive or negative?

- What assumptions might someone make about the author of this article based on her name and the title of the article?

- "Ashkenazi Eyes" is part of a book entitled The Flying Camel: Essays on Identity by Women of North African and Middle Eastern Jewish Heritage. What images and perspectives does this title conjure up for you? What impact does this have on your responses to the previous questions?

Ashkenazi Eyes

When I was a child, I had a hard time saying I was American. If pressed, I said I was Californian. Los Angeles, where I grew up among diverse cultures, felt more accessible and familiar than the great expanse of America, with my images of Dick-and-Jane families who were far away from my frames of reference. My world was multicultural—from the intimacy of my home, shared with my Iraqi-Indian Jewish father and Russian-American Jewish mother, to our circles of friends, to my schools.

My Jewishness factored significantly into my struggle with claiming American identity. My neighbor, for example, regularly reminded me that I was not welcome in her house on Christmas Day, though she was happy to be my best friend the other 364 days a year. My early idealism also factored into the equation: even at a young age, I was painfully aware that America had not lived up to its credos. I stopped saying “and justice for all” during the Pledge of Allegiance once I learned about the experience of African Americans.

Discussions with my immigrant father, who appreciated the freedoms he found in this country, forced me to question my distancing from American identity. As I learned about the history of activism in this country, I came to see that the very struggles to realize America’s promise of democracy, liberty, and equality are in fact a quintessential part of what it means to be American. This perspective afforded me a window through which I might comfortably claim being American.

When I traveled to other parts of the world, I realized that I had no choice but to identify as American—both because of personal experiences of feeling foreign and because through the eyes of people of other nationalities, there was little chance I would be mistaken for anything but American.

Still, “American” continues to fall short of representing my cultural identity or even nationality. Even “American Jew” does not fully describe me, because the term conjures up images that reflect only half of me—bagels and lox, Woody Allen, the Holocaust, yarmulkes, and ancestors from Eastern European shtetls. People do not seem to realize that “American Jew” also means chiturni for dinner, a hamsa around the neck to ward off the Evil Eye, a henna party before marriage, and ancestors from Poona, India and Basra, Iraq.

I have hazel-green eyes—“Ashkenazi eyes,” people tell me. These eyes and light skin conceal my Iraqi-Indian heritage, rendering half of me invisible. Before speaking with me about my experience or background, most people presume I am Jewish, and by that they mean Ashkenazi or white. Because I am especially close to my father’s side of the family, it is difficult to have my ethnicity defined by others in a way that does not recognize my Mizrahi identity. People who are dark-skinned or still hold traces of an accent may tire of the question, “Where are you from?” But I would welcome the rare opportunity to round out people’s perceptions of me.

Julie Iny, "Ashkenazi Eyes," The Flying Camel: Essays on Identity by Women of North African and Middle Eastern Jewish Heritage, ed. by Loolwa Khazzoom, (New York: Seal Press, 2003).

Discussion Questions (Part 2) - After Reading

- If Julie Iny were to do the 5 part identity activity we did earlier, how might she have filled out her card?

- With what part of her identity was Julie uncomfortable? Why?

- Has there ever been a situation in which your identity has made you uncomfortable or the actions of others have caused you to question some part of your identity?

- What experiences and knowledge help Julie Iny come to terms with part of her identity? Why did she need to come to terms with it? Is it possible to change one's identity?

- With what part of her identity does Julie still struggle? How do the actions of strangers reinforce this struggle?

- What kinds of assumptions might people make about your identity?

- Revisit the assumptions made about Julie Iny and her article before you read it. How many of the assumptions were correct? How many were inaccurate? To what degree do we judge someone else's identity by visual clues and/or names?

Claire

Claire

"Claire" by Dawoud Bey, 2004

Dawoud Bey, Claire, 2004. Pigment Print, with interview by Dan Collison and Elizabeth Meister.

Image courtesy of Dawoud Bey.

Commissioned by the Jewish Museum for the exhibition The Jewish Identity Project: New American Photography.

Claire Saxe Interview excerpts

My name’s Claire Saxe, I’m 16 years old.

My father is mostly Russian, and my mom is I think about half Russian, my grandmother is part Native American. She’s Ojibwe and lives on an Indian reservation in northern Wisconsin.

I’m not very religious. I think 3/4 of my family either is or was Jewish at one point in their life, but I’m not really religious at all. Whenever people ask what religion I am, I mention that parts of my family are Jewish but I’m not religious, but I think culturally I identify more with being part Native American than I do with being part Jewish. Which is interesting, because I’m such a small percentage Native American, but I think just because I’ve been to the reservation every year since I was a baby, I’m so familiar with the culture and everything because of my grandma, it feels closer to me than Judaism does.

In 6th grade I did research on Ojibwe religion, ‘cause when all my friends were getting Bat Mitzvahed and I was like well, maybe I can find something of my own. And it wasn’t really what I had sort of romanticized it to be, but there’s still something that it has been in my head all these years that I like, and I’m not really sure what you’d call that. I mean, I really like the idea of being connected to nature and your surroundings, and acknowledging the life of everything around us, and it’s sort of spirit and existence. I find that really comforting, you know feeling at home, and feeling like I’m not alone when I’m in a forest surrounded by trees, because everything around me is alive…

When I was about 13 and all my friends were getting Bat Mitzvahed I was kind of upset, and I asked my mom why she hadn’t made me Jewish when she had the chance. And I guess part of me does still want that a lot, sort of wants to have that identity, to have that part of myself more concretely. But religion now isn’t a part of my identity so much, because I didn’t have any sort of religious experience growing up. So I don’t think I need it, I’m not dependent on it. But if I grow up and find something that feels right, I think I would like to have that as part of who I am, and to pass on to my children, so they do have that. And since such a large part of my family and a large part of my ancestors were Jewish, I’d probably investigate that first. But it’s not something that I'm yearning for and that I need, because it's not something that I've had my whole life.

An excerpt from an interview with Claire Saxe, 2004, conducted by Dan Collusion and Elizabeth Meister, which accompanies the photograph Claire by Dawoud Bey.

Discussion Questions (Part 1) - Looking at the Photograph

- Describe what you see in this picture. How is this girl posed? What is she wearing? Where is she sitting? How would you describe her expression?

- What do you think this girl is communicating to you as the viewer?

- Does she seem approachable? Reserved? Other?

- Based upon what you see in the picture, what assumptions might someone make about the identity of this girl? What is the basis for those assumptions?

Discussion Questions (Part 2) - After Reading Transcript

- If Claire Saxe was to do the 5 part identity activity we did earlier, how might she have filled out her card?

- What parts of her identity have caused Claire to do research about her people and religion? Do you think the research has helped her become more comfortable with who she is? Why or why not?

- Describe a situation in which what others were doing has caused you to question some part of your identity.

- Only a fraction of Claire's heritage is Ojibwe but this is the strongest part of her identity. What has reinforced this part of her identity? How do you think experiences in our lives help shape our identity?

- What is an experience that has helped shape your identity?

- Revisit the assumptions made about Claire Saxe before you read her transcript. How many of the assumptions were correct? How many were inaccurate? To what degree do we judge someone else's identity by visual clues and/or names?

Jacob

Jacob

Jacob, by Dawoud Bey, 2005

Jacob, by Dawoud Bey, 2005. Pigment Print, with interview by Dan Collison and Elizabeth Meister.

Courtesy of Dawoud Bey. Commissioned by the Jewish Museum for the exhibition The Jewish Identity Project: New American Photography.

Jacob Goldstein interview excerpt

My name is Jacob Goldstein and I’m 15.

My father was Belizean, my mom is American, and I’m Jewish. So I’m one of a kind, you could say. I didn’t know my dad because he died when I was little. But I grew up with my mom, and she’s raised me all by herself, and she’s done a great job.

A lot of people thought I was adopted. but, when people think I’m adopted, I really don’t think anything of it, I just have to tell them that, no she’s my mom and my dad was Black.

I identify myself as being Black, but I also identify myself as being Jewish too. I think of myself more as an individual than like any other person, because I’m both, like I’m Jewish and I’m black, so I’m different than most other people. I like being different than other people, I like being a leader, I don’t like to follow other people and, what they do.

People base too much on the way people look, like the way people dress, like they look at me, and might think, like, I’m in a gang or something. That’s just because of the way I dress. You can’t really put an identity on someone that you don’t really know. When people don’t know that much about you and you’re just like, oh, I forgot to tell you, I’m Jewish, they’re like, what? That’s something they’d never expect.

An excerpt from an interview with Jacob Goldstein, 2005, conducted by Dan Collusion and Elizabeth Meister, which accompanies the photograph Jacob by Dawoud Bey.

Discussion Questions (Part 1) - Looking at the Photograph

- Describe what you see in this picture. How is this boy posed? What is he wearing? Where is he sitting? How would you describe his expression?

- What do you think this boy is communicating to you as the viewer?

- Does he seem approachable? Reserved? Other?

- Based upon what you see in the picture, what assumptions might someone make about the identity of this boy? What is the basis for those assumptions?

Discussion Questions (Part 2) - After Reading Transcript

- If Jacob Goldstein was to do the 5 part identity activity we did earlier, how might he have filled out his card?

- Jacob says that people often make assumptions about him based on his skin color or the way he dresses (e.g. that he is adopted or that he is a member of a gang). He also says that people are surprised to learn that he's Jewish. How do you think these experiences shape the ways that Jacob thinks about and expresses his identity?

- How might people judge you based on what they can see? How does that influence the ways you think about and express your identity?

- Why does Jacob think of himself as an individual/different? Do you agree with Jacob? Is he different?

- Jacob says he likes to be different. In what ways do you like to be different? In what ways, do you want to blend in with others?

- Revisit the assumptions made about Jacob Goldstein before you read his transcript. How many of the assumptions were correct? How many were inaccurate? To what degree do we judge someone else's identity by visual clues and/or names?

Choices in Little Rock

More identity exploration exercises and texts can be found in Part 1 of Facing History and Ourselves “Choices in Little Rock” curriculum.

The Hebrew Mamita

"The Hebrew Mamita" by Vanessa Hidary, a spoken word performance reflecting on what it means to "look Jewish." Video is available on Youtube: www.youtube.com/user/hebrewmamita#p/u/7/VoENRgzP_VI. (Contains profanity.)

How Jews Became White Folks

Brodkin, Karen. How Jews became white folks and what that says about race in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998.

Be'chol Lashon (In Every Tongue)

The website of the organization Be'chol Lashon (In Every Tongue) includes resources, research, and advocacy related to Jewish diversity.

The Jewish Identity Project: New American Photography

The Jewish Identity Project: New American Photography catalogue, from the traveling exhibition created by the Jewish Museum in New York. (Includes the photographs Claire (2004) and Jacob (2005) by Dawoud Bey.) Information on the exhibition and catalogue: www.thejewishmuseum.org/exhibitions/JewishIdentityProject.

Photographer Dawoud Bey's website

Photographer Dawoud Bey's website, www.dawoudbey.net, contains images of other works similar to Claire and Jacob (though not necessarily of Jewish students), under photographs: class pictures.

For a great lesson on Jewish identity, I used the story of Senda Berenson (Ì¢âÂÒMother of WomenÌ¢âÂã¢s BasketballÌ¢âÂå) from the JWAÌ¢âÂã¢s Ì¢âÂÒThis Week in HistoryÌ¢âÂå (http://jwa.org/thisweek/Mar/22..., along with a New York TimeÌ¢âÂã¢s story about Drew Lovejoy, the seventeen-year-old three-time winner of the all-Ireland dancing championship (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03.... My seventh graders loved it!