Organizing

Excerpt from Pauline Newman’s unpublished memoir, in which she recalls the beginning of the 1909 garment workers’ strike

Despite these inhuman working conditions the workers – including myself – continued to work for this firm. What good would it do to change jobs since similar conditions existed in all garment factories of that era? There were other reasons why we did not change jobs – call them psychological, if you will. One gets used to a place even if it is only a work shop. One gets to know the people you work with. You are no longer a stranger and alone. You have a feeling of belonging which helps to make life in a factory a bit easier to endure. Very often friendships are formed and a common understanding established. These, among other factors made us stay put, as it were…

During the early part of November an unknown (to me) source provided the money for calling a mass meeting of the shirt waist makers in the historic Cooper Union hall. The place was packed. There were many prominent speakers among them the President of the American Federation of Labor – Samuel Gompers, and Mary Dreier of the Women’s Trade Union League. The workers were urged to join the union and put an end to their exploitation. In the midst of all the admirable speeches a girl worker – Clara Lemlich by name, got up and shouted “Mr. Chairman, we are tired of listening to speeches. I move that we go on strike now!” and other workers got up and said “We are starving while we work, we may as well starve while we strike.” Pendimonium [sic] broke lose [sic] in the hall. Shouts, cheering, applause, confusion and shouting of “strike, strike” was heard not only in the hall but outside as well. There were many workers who could not get into the hall. There were no loud-speakers in those days, but word was carried to them and they joined in the cry for a strike. As one of them said, “Why not, we have nothing to lose and we may have something to gain.”

It was the 22nd of November when the strike was called. I remember the day – a grey sky, chilly winds and the winter just around the corner. However, neither the cold wind nor the cloudy sky prevented the strikers from cheering their own courage and daring as they left shop after shop to join their co-workers on the streets of New York. Despair turned to hope – marching from virtual slavery to the promise of freedom and decency. Five thousand, ten thousand, twenty thousand filled every hall available. That day was indeed a red letter day for the strikers and for the union. On this day young women laid the foundation for the powerful, constructive and influential union in the American Labor Movement, the ILGWU. As women they never did get the credit for what they contributed to the building of the present structure known all over the world as the most progressive labor organization in existence. That, however, did not prevent them from proving (and in those days to prove was essential) that women without experience can and did rise from their slumber to fight for a happier existence with determination and without fear.

During the weeks and months of the strike most of them would go hungry. Many of them would find themselves without a roof above their heads. All of them would be cold and lonely. But all of them also knew and understood that their own courage would warm them; that hope for a better life would feed them; that fortitude would shelter them; that their fight for a better life would lift their spirit. They were ready and willing to endure hardship of any kind until victory was in sight. And fight they did.

Rose Schneiderman’s Women’s Trade Union League Report

I commenced my work as East Side organizer on the 1st of April, 1908, and for a period of four months felt that I had attempted one of the most difficult industrial problems, in a most critical time of the struggle of the working class. For a time I felt that all was hopeless and dark, and that it were better for me to return to the factory. It is a very difficult thing to tell people who are starved for the lack of work, “Organize now as you never did before and endeavor by the might of your numbers to prevent industrial panics in the future!” The answer comes, “I am hungry! Give me work, and then we will speak of what is to be done.” I therefore began to visit East Side unions which had women in them and simply stated that the Women’s Trade Union League had put an organizer into the field and that she was always ready to do all in her power to help to bring the girls of the trade into the organization; also, that the League was prepared to open English classes, where trades-unionism would be taught together with the English language.

The White Goods Union

I visited the White Goods Union which, twenty-eight months ago had a membership of three hundred, and found that all that they were left with, were the officers. We conferred together, and they asked whether the League would assist them financially in holding mass-meetings. I said that it would, and we decided that a concert be arranged. This was a failure, as very few of the girls attended. We then decided to have a May Dance for the East Side women unionists, and invitations were distributed among the unions…Thought the attendance was not as large as we anticipated, good work was done, as those who came listened to the gospel of trade unionism from the lips of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, John Dych and Jacob Pankin, and when the girls left, they were much wiser as to woman’s place in industry….

The Dress Makers’ Strike

In the beginning of November last, the League was called to assist the dress makers of a Fifth Avenue shop, who were striking to resist a change of system from “piece work” to “week work.” The girls were alone, inexperienced and without any reserve funds. Brother Pine of the United Hebrew Trades, to whom they applied for assistance, was not in the position to give them all the aid they needed…The first thing we did, was to organize the girls into a Union. We found that the girls of other factories understood that the fight was theirs as well, as a principle was involved which would have a vital effect upon them. They, therefore, responded to an appeal for assistance by making collections among themselves…Little by little the girls found employment at other shops and the strike gradually dwindled away. At present, we have a Dressmakers and Costumers’ Local #60 of the Garment workers, of which I have the honor of being president, and there is good promise for the development of a big, strong organization in the near future….

In conclusion, I would say that the organization of women with its many difficulties – the different nationalities and the passive toleration of many wrongs – is a great problem, which requires constant vigilance and attention besides personal labor of everyone interested in the movement, for its solution. I would also suggest that perhaps, we, who are trying our best to solve this problem, have not considered seriously enough the joyless life of the working woman, and that, perhaps, wee have not done all that is necessary to make the labor organization a social as well as an economic attraction. We have insisted on the business-side of labor organization, forgetting the while, that women are not as yet wholly business-like, thank goodness! Let us idealize more the trade union movement, show that it is the way towards the emancipation of the worker, and with that aim in view and a great deal of hard, earnest, perservering [sic] work, the victory will be ours. Respectfully submitted, Rose Schneiderman

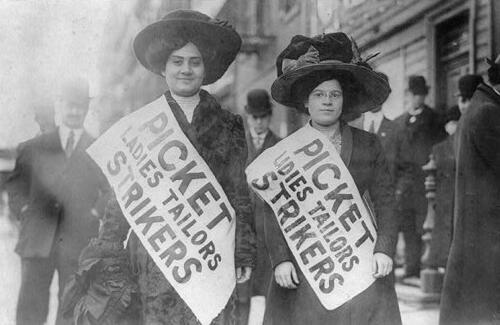

Ladies Tailors Strikers, February 1909

Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Sarah Rozner discusses striking and making a living

The three of us were striking, my brother Dave, my sister Fanny, and me. Fanny was 15 and she’d be on the corner selling papers for the strike. She had a good time; she was young and gay and singing. My brother’s first wife was my girlfriend, and we had one good skirt between us. If she went on the picket line, we raised the hem, because she was much shorter than I; when I went on the picket line, I’d let the hem down. That’s the way we lived.

Fanny got a couple of pennies from selling the socialist papers, enough for a couple of loaves of bread. But we were hungry. They didn’t feed us in the strike hall. Sedosky, a Jewish writer, had a restaurant where for 15 cents they used to get some strike tickets for a full meal. But that was only for single men. They finally did give us some tickets to a storehouse. It was on Maxwell or Jefferson Street and was a storehouse for strikers who had family responsibilities. They had food of various sorts: bread, herring, beans, rice. None of the family wanted to go there, so I went alone. I brought home the “bacon.”

Discussion Questions

- What were the conditions that caused workers to organize?

- Why did the speakers/writers decide to join a union? Give specific examples from the documents.

- How do the writers/speakers describe the feeling of working collectively with others to demand changes in their working conditions?

- Look at the picture. What do you see going on in the picture? Based on the accounts given in this document study, what conclusions can you draw about these women?

- What kinds of activities did the labor organizers engage in to get women workers to join unions? What kinds of arguments did they make?