Sources about Activists and Allies

Exodus/Shemot 22:20

20 You shall not wrong a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think the stranger, widow and orphan are grouped together for special consideration for protection?

- Why do you think a reason is given for not wronging a stranger, while no reason is given for not ill treating the widow and orphan?

- Why do you think a punishment is given for wronging the widow and orphan, when it is rare that Torah cites specific punishments for wrong-doing?

- Looking at the phrasing in the last sentence (verses 22-26), what is the effect of comparing the widow and the orphan in general to the wife and child of the reader?

- What do these verses of Torah teach about our responsibility to others?

"A Challenge to Know and Tell"

From the schoolroom where I had been giving a lesson in bed-making, a little girl led me one drizzling March morning. She had told me of her sick mother, and gathering from her incoherent account that a child had been born, I caught up the paraphernalia of the bed-making lesson and carried it with me.

The child led me over broken roadways — there was no asphalt, although its use was well established in other parts of the city, — over dirty mattresses and heaps of refuse... between tall, reeking houses whose laden fire-escapes, useless for their appointed [intended] purpose, bulged with household goods of every description. The rain added to the dismal appearance of the streets and to the discomfort of the crowds which thronged them, intensifying the odors which assailed me from every side...

The child led me on through a tenement hallway... up into a rear tenement, by slimy steps whose accumulated dirt was augmented that day by the mud of the streets, and finally into the sickroom.

All the maladjustments of our social and economic relations seemed epitomized in this brief journey and what was found at the end of it. The family to which the child led me was neither criminal nor vicious. Although the husband was a cripple, one of those who stand on street corners exhibiting deformities to enlist compassion, and masking the begging of alms by a pretense at selling; although the family of seven shared their two rooms with boarders — who were literally boarders since a piece of timber was placed over the floor for them to sleep on — and although the sick woman lay on a wretched, unclean bed, soiled with a hemorrhage two days old, they were not degraded human beings, judged by any measure of moral values.

In fact, it was very plain that they were sensitive to their condition, and when at the end of my ministrations they kissed my hands (those who have undergone similar experiences will, I am sure, understand), it would have been some solace if by any conviction of the moral unworthiness of the family I could have defended myself as a part of a society which permitted such conditions to exist. Indeed, my subsequent acquaintance with them revealed the fact that, miserable as their state was, they were not without ideals for the family life and for society of which they were so unloved and unlovely a part.

That morning’s experience was a baptism of fire. Deserted were the laboratory and the academic work of the college. I never returned to them. On my way from the sickroom to my comfortable student quarters my mind was intent on my own responsibility. To my inexperience it seemed certain that conditions such as these were allowed because people did not know, and for me there was a challenge to know and to tell. When early morning found me still awake, my naïve conviction remained that, if people knew things — and “things” meant everything implied in the condition of this family — such horrors would cease to exist, and I rejoiced that I had had a training in the care of the sick that in itself would give me an organic relationship to the neighborhood in which this awakening had come...

Within a day or two a comrade from the training-school, Mary Brewster, agreed to share in the venture. We were to live in the neighborhood as nurses, identify with it socially, and, in brief, contribute to it our citizenship. That plan contained in embryo all the extended and diversified social interests of our settlement group to-day.

Discussion Questions

- What does Lillian Wald mean when she says the family are not “degraded human beings”? Why does she feel it is necessary to explain this?

- What does Wald see as her responsibility as an ally to this family?

- What does she mean by having an “organic relationship to the neighborhood” and identifying “with it socially”? How is this an important part of the project?

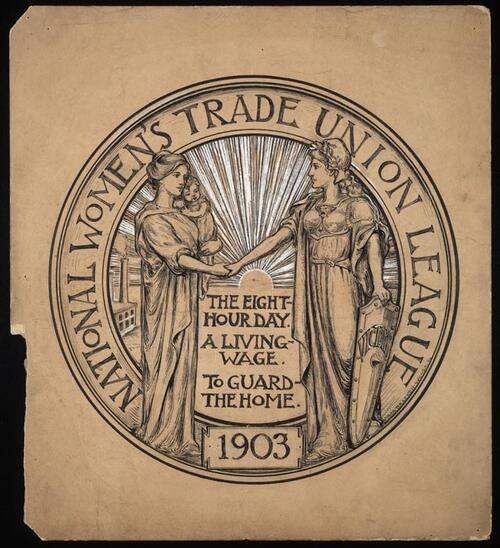

Seal of the National Women's Trade Union League, 1908-1909

Institution: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. LC-DIG-ppmsca-02954 (scan from b&w copy photo in Publishing Office)

Discussion Questions

- Who are the two women in the image? What does this image and the way these women are depicted tell us about the Women’s Trade Union League?

- The seal lists three goals: the eight hour day, a living wage, and “to guard the home.” What does each of these refer to, and why were these so important to the Women’s Trade Union League? Why would a women’s organization in particular address these three issues?

Sarah Rozner's role in the 1915 strike

Sarah was a Jewish immigrant garment worker from Hungary living in Chicago, who became involved in labor activism in the 1910s. In this excerpt, she recalls her role providing support through the union during a 1915 strike.

“Not only did I got out on strike, but I became the chairlady of the strike hall. I was there day and night, taking care of a multitude of people: feeding them, sending them out on the picket line, and being on the picket line. Not only that. I had to distribute money, aid, help, whatever was necessary. I remember a canvas baster from my shop who earned, I think, five or six dollars a week. I made it my business to give him eight dollars in strike funds because I knew that he was scabbing-inclined.”

Discussion Questions

- What kind of aid did the union provide? Why?

- Why do you think Sarah would give more money to someone who was inclined to scab?

"What We Learned at Unity House."

A trade union is something more than an organization to fight for our rights, to increase our wages in the shop. It is also a great cooperative group which should spend together as well as earn together, which should enjoy together as well as suffer together, which should learn together as well as fight together… We learned at Unity House that there is a mysterious bond between working sisters just as there is between sisters in a family. And we only wished that devotion and that sisterhood would have more opportunity to lift its head in our shops.

Discussion Questions

- What kinds of activities does Newman think should ideally be part of a union?

- Why do you think Newman believes workers in a union together should engage in these activities beyond the workplace?

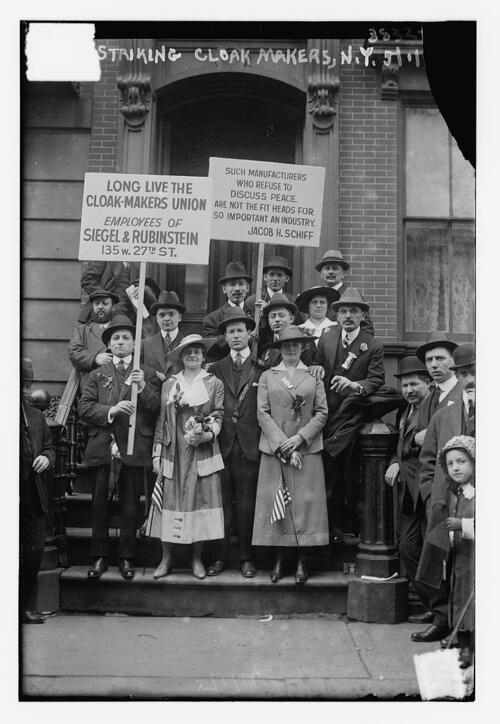

Strike of Cloak Makers, May 1, 1916

Institution:U. S. Library of Congress' Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ggbain 21569.

Discussion Questions

- What is going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that?

- In some cases, the owners of factories that exploited workers and treated laborers unfairly were Jewish. This was the case in the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, as well as in the case of this particular cloak shop strike. How (if at all) does this change your understanding of Jewish involvement in labor struggles?

- One of the signs held by a striking worker contains a quote from the Jewish philanthropist Jacob Schiff. What does Schiff say about the responsibility of manufacturers (the heads of factories)? What do you think this meant to the strikers? Do you agree with Schiff?

- Do you think it is important to learn about Jewish injustice as well as Jewish support for social justice? Why or why not?

- Can you think of any other examples of times when some Jews were working against justice, rather than for it?