Emma Lazarus

"Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free."

Emma Lazarus's famous lines captured the nation's imagination and continues to shape the way we think about immigration and freedom today. Written in 1883, her celebrated poem, "The New Colossus," is engraved on a plaque in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. Over the years, the sonnet has become part of American culture, inspiring everything from an Irving Berlin show tune to a call for immigrants' rights.

One of the first successful Jewish American authors, Lazarus was part of the late nineteenth century New York literary elite and was recognized in her day as an important American poet. In her later years, she wrote bold, powerful poetry and essays protesting the rise of antisemitism and arguing for Russian immigrants' rights. She called on Jews to unite and create a homeland in Palestine before the title Zionist had even been coined.

As a Jewish American woman, Emma Lazarus faced the challenge of belonging to two often conflicting worlds. As a woman she dealt with unequal treatment in both. The difficult experiences lent power and depth to her work. At the same time, her complicated identity has obscured her place in American culture.

Childhood & Background

Emma Lazarus was the fourth child in a wealthy family of seven children. Born in 1849 to Moses and Esther Nathan Lazarus, she grew up around New York's vibrant Union Square. Her siblings included Josephine Lazarus who was also a well known writer and a featured speaker at the 1893 Jewish Women's Congress.

Emma's early poems and translations show she had a strong classical education and a mastery of German and French. Her father Moses Lazarus recognized his young daughter's talent and began to encourage her work. In 1866, when Emma was seventeen, he privately published her first book, Poems and Translations Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Seventeen.

The Lazarus family traced their ancestry back to America's first Jewish settlers. As descendants of this pioneering group of Sephardic (Spanish and Portuguese) Jews, Emma's family belonged to a distinct Jewish upper class. From them, Emma inherited a rich pride in her Sephardic heritage, and often wrote about the medieval scholars and poets of her ancestors' land.

A prosperous sugar refiner, Moses Lazarus was eager to see his family more integrated into Christian society. He moved in wealthy Christian circles, joined the exclusive Union club, and founded, together with Vanderbilts and Astors, the elite Knickerbocker club. He also built his family a summer "cottage" in Newport with the rest of fashionable society.

Notes:

- For chronological material and Moses Lazarus' Christian society contacts see Bette Roth Young, Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995) 6-7.

- On the Lazarus family and Sephardic history see Stephen Birmingham, "Our Crowd”: The Great Jewish Families of New York (New York: Harper and Row, 1967) 29.

Anti-Semitism & the Elite

Explicit acts of discrimination were rare during the early years of Emma's life. However, in 1877 the highly publicized refusal of the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga, NY. to admit Joseph Seligman, a wealthy Jewish banker of German extraction, was a sign of change. Anti-semitism had begun to sweep over Europe; as the rates of Eastern European Jewish immigration climbed, the American climate became less tolerant.

Judge Henry Hilton, the Grand Union Hotel's owner, explained he had no objection to the Sephardic elite. Those like Emma Lazarus' family, who had lived in America since before the Revolution, were the refined, "true Hebrews." According to Hilton, only the dirty, greedy, German immigrant "Seligman Jews" were unwanted.

While Emma's devout ancestors and relatives were actively involved with the Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue, her immediate family was "outlawed" among the extended Lazarus clan because it was no longer religiously observant. Moses Lazarus, Emma's father, sought to secure a place for his family among the Christian elite.

Although Emma's friends were almost all Christian, she was usually referred to and seen as a "Jewess." As Emma knew, prejudice often lurked beneath the polite surface of wealthy society. Despite her father's efforts and her elite Sephardic background, her outsider status was never entirely erased. As she wrote in one letter, "I am perfectly conscious that this contempt and hatred underlies the general tone of the community towards us..."

Notes:

- On the Sephardic community's privilege and elevated position, see Stephen Birmingham, "Our Crowd: The Great Jewish Families of New York (New York: Harper and Row, 1967) 29, 127.

- On shifting American attitudes towards Jews, see Francine Klagsbrun, forward, Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters by Bette Roth Young (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995) xi .

- On the Grand Union Hotel and Hilton, see "Hotel Discrimination," New York Times (June 20, 1877): 1.

- For Lazarus's religious background, as well as her outsider status, see Ellen Emerson, "My dear Edith," 6 September 1876, The Letters of Ellen Tucker Emerson, vol. 2, ed. Edith E.W. Gregg (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1982) 225. Also see Young, 44-5.

- For Lazarus's quote on the community's contempt see her letter in Philip Cowen, "A Budget of Letters," American Hebrew 33 (Dec. 9, 1887): 8.

Emerson as Mentor

In 1868 the precocious young Emma Lazarus sent Ralph Waldo Emerson a copy of her first book. Over the next few years, Emerson became a trusted mentor, offering notes on her poems that ranged from enthusiastic praise to pointed criticism. But whether complimenting or criticizing, Emerson remained a supportive reader.

Lazarus assumed her poems would be included in her mentor's 1874 anthology entitled Parnassus. Instead she was surprised and angry to find her work missing from Emerson's selections. She sent him a strong letter demanding an explanation. "Your favorable opinion having been confirmed by some of the best critics of England and America," she wrote, "I felt as if I had won for myself by my own efforts a place in any collection of American poets, and I find myself treated with absolute contempt in the very quarter where I had been encouraged to build my fondest hopes."

There is no record of Emerson's response, but their friendship seemed to have survived this rift. Lazarus's respect for Emerson remained constant, and she often praised him in essays and poems. Emerson also invited his "dear friend" to Concord in 1876, and again in 1879.

Notes:

- For Emerson's comments to Lazarus, see Letters to Emma Lazarus in the Columbia University Library, Ralph L. Rusk, ed. (New York: New York Public Library, 1949) 3-16. For example, see "My dear friend," 19 November 1868, p. 9 and "My dear friend," 7 June 1869, p.11.

- For the quote of Lazarus' letter to Emerson, see Emma Lazarus, "My dear Mr. Emerson," 27 December 1874, included in Max I. Baym, "Emma Lazarus and Emerson," Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 38 (1948): 269-270.

- For Lazarus's thoughts on Emerson, see Emma Lazarus, "Emerson's Personality," Century 24 (February 1883): 454-455 and "To R.W.E." Critic 5 (August 1884): 5-6.

- On Lazarus's visits, see Rusk 16 and Young 72. For Ellen Emerson's letter, see Ellen Emerson, "My dear Edith," 6 September 1876, The Letters of Ellen Tucker Emerson, vol. 2, ed. Edith E.W. Gregg (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1982) 225.

Success

Emma Lazarus's second book, Admetus and Other Poems, was published in 1871 to excellent reviews. Illustrated London News declared, "Miss Lazarus must be hailed by impartial literary criticism as a poet of rare original power."

Her only novel, Alide: An Episode in Goethe's Life, appeared three years later. An adaptation of the German writer's autobiography, this book was also highly praised. The famous Russian author Turgenev told Lazarus that, "An author who writes as you do...is not far from being himself a master."

Throughout the 1870's, Lazarus published poetry in popular magazines, most frequently in Lippincott's. By 1882, over 50 of her poems and translations had appeared in mainstream periodicals. In 1876, she also completed a drama, The Spagnoletto. While the play was praised by friends like Thomas W. Higginson, it was privately published and never performed.

In 1881, her translations of the German Jewish poet Heine garnered Lazarus the best reviews yet. The Critic called her Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine, "... a copy of an artist's work made by an artist's hand."

Notes:

- Illustrated London News is quoted in an ad placed in Emma Lazarus, Songs of a Semite: The Dance to the Death and Other Poems (New York: The American Hebrew, 1882).

- For Turgenev's letter, see Turguéneff, Ivan, "Dear Miss Lazarus," in Letters to Emma Lazarus in the Columbia University Library 16.

- On Lazarus' magazine publications, see Young 7 and the selected bibliography in Dan Vogel, Emma Lazarus (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980) 174-6.

- Higginson's praise is noted in Lazarus's letter to him, 4 November 1876 (courtesy of Boston Public Library.) Quoted in Baym 273 footnote 25.

- For quotes praising Lazarus's Heine translation, see Aaron Kramer, "The Link Between Heinrich Heine and Emma Lazarus," Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 45 (1955): 250-1.

Literary Lions

Emma Lazarus moved comfortably in New York's elite social and artistic circles. She was a fixture at her good friends the Gilders' famous Friday night salons. Recalling one of those nights, Lazarus wrote, "Helena's 'Friday Evngs.' grow more & more brilliant- last Friday she had about 50 people, literary, artistic, social 'lions' of all kinds."

Lazarus's correspondents included many American intellectual figures of the day, and their letters to her are marked with deep respect. E.C. Stedman, who was one of the most influential poets and critics of the time, thanked her for a recent critique, remarking, "There is no opinion I value more than that of one whom I recognize as a true artist, as a genuine member of my own guild."

Her busy European travels also put her in contact with luminaries like Robert Browning and William Morris. As Henry James wrote her, "You appear to have done more in three weeks than any lightfooted woman before; when you ate or slept I have not yet made definite."

Lazarus' social life was filled with cultural events. With her friends she shared concerts, plays, and galleries, and constantly discussed literature. Her letters home from overseas are full of exuberant experiences, "drinking in with every sense the spirit of the antique world and the beauty of life." As she wrote, "My own curiosity and interest are insatiable."

Notes:

- For Lazarus' quote on the Gilders, see Emma Lazarus, "My dear Rose," 29 January 1884 in Young 199.

- On the Gilders' Friday nights see John Arthur, The Best Years of the Century: Richard Watson Gilder, Scribners Monthly and Century Magazine, 1870-1909 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981) 2.

- For the quote from E.C. Stedman see his letter to Lazarus, 2 January 1885 in Letters to Emma Lazarus in the Columbia University Library 28. On E.C. Stedman's reputation see Young 272.

- James' quote is from Henry James, "Dear Miss Lazarus," 5 February 1884 in Young 212-3.

- Quotes from Lazarus' letters home from Europe to her friend Helena deKay Gilder can be found in: "My dear Helena (& Richard!)," 23 February 1886 in Young 144 and "My dear Helena," 29 June 1886 in Young 155.

Heinrich Heine

In the German Jewish poet Heine, Emma Lazarus found an important kinship and inspiration. Her interest in him spanned the course of her career. From her early translations to her essay "The Poet Heine," which appeared in The Century three years before her death, he was a constant subject.

His work, like her own, ranged from the romantic to the overtly political and satirical. She also described Heine's Jewish identity much as she described her own: "No enthusiast for the Hebrew faith,...he was none the less eager to proclaim himself an enthusiast for the rights of the Jews and their civil equality."

As Lazarus explains, Heine felt the pressure and pull of different worlds on his art:

He was a Jew, with the mind and eyes of a Greek....In Heine the Jew there is a depth of human sympathy, a mystic warmth and glow of imagination... an indomitable resistance to every species of bondage.... On the other hand, the Greek Heine...[possesses] a pure and healthy love of art for art's own sake, with which the somber Hebrew was in perpetual conflict.

This description provides a useful key towards understanding Emma Lazarus's own work. She too moved between celebrating Greek myths like Admetus and legendary Hebrew scholars like Rashi. And she believed in both the ideals of art for art's sake and poetry that called for social justice.

Notes:

- For Lazarus's quote on Heine's Jewish identity, see Selections from Her Poetry and Prose, ed. Morris U. Schappes (New York: Cooperative Book League, 1944) 87. (Note: page numbers vary in later reprints of Selections; see p. 91 in 1967 edition)

- On Lazarus's own feelings about her Jewish identity, see Emma Lazarus, "My dear Doctor Gottheil," 25 February 1877, The Letters of Emma Lazarus, 1868-1885, ed. Morris U. Schappes (New York, New York Public Library, 1949) 21.

- For Lazarus's quote on Heine's dual nature, see Selections 90. (see p.93 in 1967 edition)

American Author

Publishing in mainstream magazines like The Century, Lazarus often dealt with the question of her country's unique cultural development. In her essay "American Literature" she passionately defended the fresh, distinctly American tradition she found emerging in authors like Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Her short story, "The Eleventh Hour," pointed to how some people mistakenly bring "the miniature standard of Europe...to measure and judge a colossal experiment." Her main character, Richard Bayard, states that "art and beauty must and will survive" on this new continent, although it is too soon to know what new forms they will take.

And in the poem "How Long," Lazarus urged American poets to find their new forms and no longer hail leaders "from overseas." American writers must reflect the beauty of the land in which they live, not dully echo what was created for England's landscape.

Lazarus hoped that an American "genius" would arrive to bring this new tradition to greater heights. In a letter to her friend E.C. Stedman, a respected and influential poet and critic, she criticized his thesis that American culture lacked the great themes necessary to inspire genius. As she explained, "I have never believed in the want of a theme. Wherever there is humanity, there is the theme for a great poem."

Notes:

- For Lazarus's essay, see "American Literature," Critic 1 (June 1881): 164.

- For quotes and a reading of "The Eleventh Hour," see Young 256. For the story itself, see Emma Lazarus, "The Eleventha Hour," Scribners 16 (June 1878): 252-56.

- Lazarus's quote on no want of great themes is from the letter "My dear Mr. Stedman," Summer [?] 1881 in The Letters of Emma Lazarus, 1868-1885 67-8.

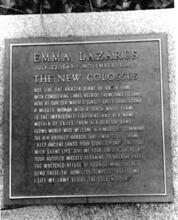

The New Colossus

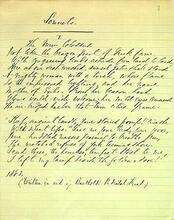

Emma Lazarus wrote "The New Colossus" in 1883 for an art auction "In Aid of the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund." While France had provided the statue itself, American fundraising efforts like these paid for the Statue of Liberty's pedestal. In 1903, sixteen years after her death, Lazarus' sonnet was engraved on a plaque and placed in the pedestal as a memorial.

The famous sonnet echoes many of the conflicting identities and ideals Lazarus dealt with in her own life. As an American author, she felt that ancient lands could keep their old traditions and "storied pomp." At the same time, Lazarus invoked her ancient Greek ideals by transforming the "brazen giant " into a "Mother of Exiles" who retains Greek majesty, beauty and defiance as a new Colossus. The compassion of the lines "huddled masses yearning to breathe free" welcomes the tired immigrants, but the following image of the "wretched refuse of your teeming shore" hints at the condescension these refugees were to suffer. And while this Mother of Exiles' eyes command, and she stands alone beacon to all the world, she is still an ambiguous figure of power, speaking only with "silent lips."

Struggling beneath the poem's surface, these tensions—between ancient and modern, Jew and American, voice and silence, freedom and oppression—give Emma Lazarus's work meaning and power. As James Russell Lowell wrote, her " sonnet gives its subject a raison d'etre."

Notes:

- See the analysis of the "New Colossus" in Diane Lichtenstein, Writing Their Nations: The Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Women Writers (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).

- For Lowell's quote see his letter to Lazarus, 17 December 1883, Letters to Emma Lazarus in the Columbia University Library, ed. Ralph L. Rusk (New York: New York Public Library, 1949) 74.

Poet or Poetess?

Many late nineteenth century American women writers, including Julia Ward Howe and Harriet Beecher Stowe, found success as authors. Still, they were often seen as a "damned mob of scribbling women." A well respected "poetess" like Lazarus was always placed one notch below male poets.Even admirers condescended to her—"She spoke like a man, but felt like a true woman."

Lazarus was well aware of her predicament, as poems like "Echoes" and "Sympathy" illustrate. But in spite of her view of the limits on women writers, Lazarus was outspoken about so-called manly themes like literature, war and religion. Her series of articles, "Epistle to the Hebrews," the poems of Songs of a Semite, and her impassioned defense of American literature are just a few examples of her influential writings.

After Lazarus's death, however, her embarrassed family scrambled to fit her memory into a more demure and feminine form. Her older sister Josephine published a memorial essay painting Emma as a painfully shy, "withdrawn" spinster, and "a true woman, too distinctly feminine to wish to be exceptional or to stand alone and apart, even by virtue of superiority. " Her younger sister Annie worked to erase Emma's vocal Jewish identification. As literary executor—and an Anglo-Catholic convert—she refused to grant permission in 1926 to reprint Emma's Jewish poems, finding them unseemly "sectarian propaganda."

Notes:

- On late nineteenth century American women writers, as well as a citing of the Hawthorne quote, see Klagsbrun.

- For the "Spoke like a man..." quote, see Rabbi G. Gottheil, "Dr. Gottheil's Eulogy at Temple Emanu-El," American Hebrew 33 (Dec. 9, 1887): 78.

- For Josephine Lazarus's memorial essay quote, see "Emma Lazarus," Century 36 (October 1888): 877. Also reprinted in Josephine Lazarus, Introduction, The Poems of Emma Lazarus, by Emma Lazarus, vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1889) 8.

- Annie Lazarus's quote is cited in Emma Klein, Introduction, Emma Lazarus: Poet of the Jewish People, by Emma Lazarus, ed. Emma Klein (Arthur James, 1997) 32.

Early Jewish Themes

One persistent misunderstanding of Emma Lazarus is that she moved overnight from complete ignorance of her people to absolute devotion. In reality, Lazarus often treated Jewish themes before she became an outspoken advocate in the early 1880s. For example, her translations from German to English of medieval Hebrew poets were published in the magazine The Jewish Messenger in 1879 and also in Rabbi Gustav Gottheil's 1887 book of hymns. And her play, The Dance to Death, which dealt with the persecution of Jews in medieval Germany, was completed years before its 1882 publication.

An 1867 poem, "In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport," shows how Lazarus's treatment of Jewish themes changed over the course of her career. Modeled after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Jewish Cemetery at Newport," her poem significantly revises his conclusion. While Longfellow's last stanzas insist that "dead nations never rise again," Lazarus concentrates on the synagogue and its living power—"The sacred shrine is holy yet."

When Lazarus shifted her attention from the Hebrew past to the present plight of Jewish immigrants, she spoke again of Longfellow's poem. In an 1882 essay, she lambasted his final stanzas, arguing that the Jewish people's current suffering in Eastern Europe, "prove[s] them to be very warmly and thoroughly alive." Using the same material, Lazarus moved from carefully crafted irony to an outspoken cry against ethnic prejudice.

Notes:

- For the argument that Lazarus often treated Jewish themes before 1882, see Morris U. Schappes, appendix ("Emma Lazarus's Interest in the Jews") in Selections from her Poetry and Prose 105.

- For the quote from Lazarus's essay on Longfellow see Selections from her Poetry and Prose 98.

Spokesperson & Prophet

A particularly vicious wave of anti-Semitism swept Eastern Europe in the 1880's. Organized Russian massacres of Jews called pogroms sparked mass Jewish flight to America. Lazarus responded with some of her most powerful work. Because her popularity enabled her to reach a broad audience, she became both a spokesperson for and a fiery prophet of the American Jewish community.

In secular magazines, she railed against international anti-Semitism as well as the false stereotypes that fostered dangerous prejudice against Jews everywhere—even in America. At the same time, she used Jewish publications to inspire passion for a new homeland in Palestine.

Her serial articles, "Epistle to the Hebrews," appeared in American Hebrew, a journal popular among middle-class American Jews. Lazarus called on her readers to join in creating a new nation, reminding them that, "Until we are all free, we are none of us free." While Lazarus's language sometimes reflected her elitism and social Darwinist beliefs—in one poem immigrant Jews crawl, "blinking forth from the loathsome recesses of the Jewry..."—her forward thinking ideas contributed to what was soon to be termed Zionism.

Lazarus's book Songs of a Semite was published in 1882 and celebrated by many as her best work. It consisted of Jewish themed poems as well as a lyric drama. Lazarus dedicated the play, The Dance to Death, to English author George Eliot (pictured, right), a source of inspiration for her ideal of a new Jewish nation.

Notes:

- For Lazarus's work in secular magazines, see for example "The Jewish Problem." Century, 25 (February 1883): 602-11 (in particular p. 608) and "Russian Christianity versus Modern Judaism." Century 24 (May 1882): 48-56. These essays are also printed, in part, in Selections from her Poetry and Prose.

- For Lazarus's quote from "Epistle to the Hebrews" see Selections from her Poetry and Prose 80 (p.84 in 1967 edition). The entire article series is reprinted in An Epistle to the Hebrews, ed. Morris U. Schappes (New York : Jewish Historical Society of New York, 1987).

- For Lazarus's poem including quote on "blinking forth from the loathsome recesses...", see "By the Waters of Babylon: Little Poems in Prose." Century 33 (March 1887): 801-3.

- On Lazarus's beliefs as a precursor to Zionism, see Young 9.

- For Lazarus's Hebrew poems and lyric drama, see Songs of a Semite: The Dance to the Death and Other Poems (New York: The American Hebrew, 1882).

Advocacy

In the 1880's, Emma Lazarus became increasingly convinced that "the time has come for actions rather than words." She visited Russian refugees, who lived in miserable conditions on Ward's Island in New York harbor, and volunteered at the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. Moved by the exiles' struggles, she was also aware of how little she had in common with them. While working among Russian immigrants, she would sometimes joke, "What would my society friends say if they saw me here?"

Lazarus's ideas on the importance of manual labor helped lead to the establishment of the Hebrew Technical Institute. These views also reflected her upper-class status as she spoke of "the wretched quality of work performed by the vast majority of American mechanics and domestic servants."

In 1883, Lazarus also formed the Society for the Improvement and Colonization of East European Jews. On her 1883 European trip, she met with Jewish philanthropists like Claude Montefiore to gather support. However, much to her disappointment, the organization collapsed in 1884.

Emma Lazarus's advocacy included secular causes as well as Jewish ones. She corresponded with the activist Henry George and published a sonnet in honor of his book, Progress and Poverty. She also wrote of her discussions with William Morris in an article in Century. While sympathetic to Morris' socialist ideas, Lazarus felt his theories were not applicable to America where "the avenues to ease and competency broad and numerous."

Notes:

- On Lazarus's work with Russian immigrants, and her quote about "society friends," see Philip Cowen, "A Budget of Letters," American Hebrew 33 (Dec. 9, 1887): 7.

- On Lazarus's role in the founding of Hebrew Technical Institute, see Philip Cowen, "Recollections of Emma Lazarus," American Hebrew (July 5, 1929): 240.

- For Lazarus's views on manual labor, see An Epistle to the Hebrews, ed. Morris U. Schappes (New York: Jewish Historical Society of New York, 1987) 17.

- On Lazarus's formation of the Society for the Improvement and Colonization of East European Jews, see Young 106 and, for example, "Dear Mr. Seligman," 6 February 1883 in Young 202.

- For the sonnet "Progress and Poverty," see New York Times (2 October 1881): 3.

- For quotes on William Morris, see "A Day in Surrey with William Morris," in Selections from Her Poetry and Prose 94-5. (p. 95-7 in 1967 edition)

Legacy

When Emma Lazarus died at the age of thirty-eight, she left behind a rich legacy. Memorial issues of both The Critic and American Hebrew were filled with tributes to her. John Hay mourned that her early death was not only an, "affliction to those of her own race and kindred," but also "an irreparable loss to American literature." Lazarus was one of the first renowned Jewish writers in American literary history.

She was also an important forerunner of the Zionist movement. Lazarus argued for the creation of a Jewish homeland thirteen years before Herzl began to use the term Zionism. Her "Epistle to the Hebrews" was reprinted by the Federation of American Zionists in 1900. As Henrietta Szold wrote in American Hebrew, "With her own hand she has sown the seeds that shall transform her grave into a garden..."

The memory of Emma Lazarus has continued to inspire activists throughout the years. The "New Colossus" itself is the quintessential statement for immigrant rights and freedom. The Emma Lazarus Federation of Jewish Woman's Clubs is another example of her influence. From 1951 to 1989, members of this organization fought anti-Semitism and racism while celebrating Jewish culture and striving to provide, "leadership to women in the Jewish communities in our time in the same spirit as Emma Lazarus did in hers."

Notes:

- For John Hay's remarks, see American Hebrew 33 (Dec. 9, 1887): 6.

- On Lazarus as Zionist forerunner, see Charles Angoff, Emma Lazarus, Poet, Jewish Activist, Pioneer Zionist (New York: Jewish Historical Society of New York, 1979) and also Young 9.

- For Henrietta Szold's quote, see American Hebrew 5.

- The Emma Lazarus Federation's quote is cited in Joyce Antler, The Journey Home: Jewish Women and the American Century (New York: The Free Press, 1997) 251. See Antler also for general information on the Federation.

Defining Emma Lazarus

No mystery has been more elusive than that of Emma Lazarus' private life. Biographies have been few and far between, due in part to a lack of primary sources. Most biographical works were written in the late 1940's when the hundredth anniversary of Lazarus' birth led to a renewed interest in her life. The myth of her private world is colored as much by these scholars' often unfounded opinions as by any evidence. Writings on Lazarus' love life and her choice to remain unmarried illustrate this confusion.

H.E. Jacob's 1949 biography explained that Lazarus never married because her emotional world was "fixed so firmly on her father ..." Jacob used Lazarus' play The Spagnoletto, which deals with a father's obsessive control over his daughter, as his "proof." On the other hand, Max Baym decided Emma was romantically obsessed with Emerson. "But what was Concord to her?" Baym asked, "It was Emerson and his opinion of her work—it was all!" In 1951, Arthur Zeiger not only repeated both men's ideas, but also took an unpublished manuscript poem, "Assurance," as evidence of Lazarus' "lesbian fantasy."

More recently, Bette Roth Young's 1995 book has suggested that Lazarus and Charles deKay (brother of Emma's friend, Helena deKay Gilder) were lovers. But unlike her predecessors, Young admits the evidence merits only a suggestion. The secrets of Emma Lazarus' private life remain hidden.

Notes:

- For Jacob's argument and quotes, see Heinrich E. Jacob. The World of Emma Lazarus. (New York: Schocken Books, 1949) 28, 70-1.

- For Baym's argument and quote, see Max I Baym, "Emma Lazarus and Emerson." Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 38 (1948): 271-2.

- Zeiger's dissertation is quoted in Young 18.

- On Lazarus and Charles de Kay, see Young 44-5.

- One notable biography missing from this discussion is Eve Merriam's 1957 Emma Lazarus: Woman with a Torch largely because it was not obtainable.

Media

| Title | Institution | Publication | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| A quote from Epistle to the Hebrews | |||

| Excerpts from Emerson | |||

| Letter from Henry James to Emma Lazarus | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University | ||

| Letter to E.R.A. Seligman from Emma Lazarus | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University | ||

| Transcription of a Letter from Ellen Emerson | |||

| Transcription of a Letter from Emma Lazarus to Philip Cowen, c.1883 | |||

| Transcription of a Letter to Helena deKay Gilder from Mary Hallock Foote | |||

| "A Hint to the Hebrews" | image/jpeg | ||

| "Assurance" from Emma Lazarus' Copy Book | American Jewish Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| "First View of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives Coming from Bethany" | Jewish Theological Seminary of America Library | image/jpeg | |

| "Plunge 4," a Photo of a Pogrom | YIVO Institute for Jewish Research | image/jpeg | |

| 1492 | image/jpeg | ||

| A Sensation at Saratoga | image/jpeg | ||

| Advertisement Featuring Reviews of Emma Lazarus | Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University | image/jpeg | |

| American Literature | image/jpeg | ||

| Cover page for "Admetus and Other Poems" | image/jpeg | ||

| Cover page for "Poems and Translations Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Seventeen" | Harvard University - Houghton Library | image/jpeg | |

| Cover page for "Songs of A Semite" | Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University | image/jpeg | |

| Cover Page for The Century Illustrated Monthly | image/jpeg | ||

| Cover page for The Spagnoletto | Harvard University - Houghton Library | image/jpeg | |

| Dedication page for The Dance to Death | Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University | image/jpeg | |

| Echoes | image/jpeg | ||

| Ellis Island, U.S. Immigration Station; Aliens entering the building for examination | The New York Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Emma Lazarus | University of Virginia Library | image/jpeg | |

| Emma Lazarus in bowtie outfit | American Jewish Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Emma Lazarus, 1874 | American Jewish Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Emma Lazarus, Engraving | The New York Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Excerpts from "Russian Christianity Versus Modern Judaism" | image/jpeg | ||

| Excerpts from Emerson | image/jpeg | ||

| Grave Marker for Emma Lazarus, Cypress Hill Cemetery | The New York Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Heinrich Heine | image/jpeg | ||

| Helena de Kay Gilder and Son in the Gilders' Studio | The Library of Congress - Manuscripts Division | image/jpeg | |

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow | image/jpeg | ||

| How Long | image/jpeg | ||

| In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport | image/jpeg | ||

| Interior of Turo Synagogue | John T. Hopf | image/jpeg | |

| Jewish Messenger cover page | image/jpeg | ||

| Joseph Seligman | American Jewish Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Letter from Henry James to Emma Lazarus | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University | image/jpeg | |

| Letter from Ivan Turgenev to Emma Lazarus | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University | image/jpeg | |

| Letter from John Hay to editor of American Hebrew, Nov. 26 | American Jewish Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Letter to E.R.A. Seligman from Emma Lazarus | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University | image/jpeg | |

| Lippincotts Magazine Cover Page | image/jpeg | ||

| Map of Sephardic Immigration | image/jpeg | ||

| Photo of immigrants on boat looking at the statue of liberty | The Mariners' Museum Research Library | image/jpeg | |

| Portrait of George Eliot | Sophia Smith Collection | image/jpeg | |

| Postcard of Immigrants Looking at the Statue of Liberty | YIVO Institute for Jewish Research | image/jpeg | |

| Progress and Poverty | image/jpeg | ||

| Ralph Waldo Emerson | David R. Godine, Publisher | image/jpeg | |

| Statue of Liberty | The New York Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Sympathy | image/jpeg | ||

| The Emma Lazarus Federation of Jewish Women's Clubs | American Jewish Archives | image/jpeg | |

| The Jewish Cemetery at Newport | image/jpeg | ||

| The Lazarus' Newport Summer Home, "The Beeches" | Redwood Library and Athenaeum | image/jpeg | |

| The New Colossus, from Emma Lazarus' Copy Book | American Jewish Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Title page for Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine | image/jpeg | ||

| To R.W.E. | image/jpeg | ||

| Union Square, East Side at Fourth Avenue | The New York Historical Society | image/jpeg | |

| Venus of the Louvre | image/jpeg |

Timeline

1849

Born in New York City on July 22

1866

Poems and Translations Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen; Begins correspondence with Ralph Waldo Emerson

1871

1874

Alide: An Episode in Goethe's Life (novel)

1876

The Spagnoletto (drama)

1877

Begins translations of medieval Hebrew poets from German to English

1881

Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine

1882

"An Epistle to the Hebrew" published serially in American Hebrew

1883

Travels to Europe

"New Colossus" written for Bartholdi Pedestal Fund

Founds Society for the Improvement and Colonization of Eastern European Jews

1885

Father dies

Travels to Europe

1887

"By the Waters of Babylon", a prose poem published in Century

Returns from Europe in September, terminally ill

Dies November 19 in New York City

1888

The Poems of Emma Lazarus, two-volume selection published posthumously by her sisters

1903

Bronze tablet of "New Colossus" is placed in the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty

Bibliography

Published Sources

American Hebrew 33(Dec. 9, 1887).

Angoff, Charles. Emma Lazarus, Poet, Jewish Activist, Pioneer Zionist. New York: Jewish Historical Society of New York, 1979.

Antler, Joyce. The Journey Home: Jewish Women and the American Century. New York: Free Press, 1997.

Arthur, John. The Best Years of the Century: Richard Watson Gilder, Scribner's Monthly and Century Magazine, 1870-1909. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

Baym, Max I. "Emma Lazarus and Emerson". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 38(1948):261-87.

——. "Emma Lazarus' approach to Renan in Her Essay 'Renan and the Jews.'". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 37(1947): 17-29.

Birmingham, Stephen. "Our Crowd": The Great Jewish Families of New York. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

The Century 4(1889).

Cowen, Philip. "Recollections of Emma Lazarus." American Hebrew (July 5, 1929): 229, 240-1.

——. Memories of an American Jew. New York: International Press, 1932.

The Critic 11 (Dec.10,1887).

Duyckinick, Evert A. Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America. New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873.

Elazar, Daniel J. The Other Jews. New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, 1989.

Emerson, Ellen Tucker. The Letters of Ellen Tucker Emerson. 2 vols. Edith E.W., Gregg, ed. Kent Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1982.

Grinstein, Hyman B. The Rise of the Jewish Community of New York 1654-1860. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1945.

Jacob, Heinrich E. The World of Emma Lazarus. New York: Schocken Books, 1949.

Kessner, Carole S. "Matrilineal Dissent: The Rhetoric of Zeal in Emma Lazarus, Marie Syrkin, and Cynthia Ozick." Women of the Word : Jewish Women and Jewish Writing. Judith R. Baskin, ed. Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 1994.

Klagsbrun, Francine. Forward. Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters. By Bette Roth Young Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995. ix-xv.

Kramer, Aaron. "The Link Between Heinrich Heine and Emma Lazarus". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. 45(1955).

Emma Lazarus: Collections of Poetry and Letters:

- Emma Lazarus: Poet of the Jewish People. Klein, Emma, ed. Arthur James, 1997.

- Selections from Her Poetry and Prose. Edited with an introduction by Morris U Schappes. New York: Cooperative Book League, 1944.

- The Letters of Emma Lazarus, 1868-1885. Edited with an introduction by Morris U. Schappes. New York, New York Public Library, 1949.

Emma Lazarus: Books:

- Admetus and Other Poems. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1871.

- Alide: An Episode in Goethe's Life. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1874.

- An Epistle to the Hebrews. With introduction and notes by Morris U.Schappes. New York: Jewish Historical Society of New York, 1987.

- Poems and Ballads of Heinrich Heine. New York: R. Worthington, 1881.

- The Poems of Emma Lazarus. vol 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1889.

- The Poems of Emma Lazarus. vol 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1889.

- Poems and Translations, Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Seventeen. Boston: Printed for Private Circulation, 1866.

- Songs of a Semite: The Dance to the Death and Other Poems. New York: The American Hebrew, 1882.

- The Spagnoletto. Private Printing, 1876.

Emma Lazarus: Essays, Articles, Poems:

- "American Literature". The Critic 1 (June 1881):164.

- "Banner of the Jew". The Critic 2(1882).

- "By the Waters of Babylon: Little Poems in Prose". The Century 33 (March 1887): 801-3.

- "The Eleventh Hour." Scribner's 16 (June 1878): 252-56.

- "Emerson's Personality". The Century 24 (February 1883): 454-455.

- "To R.W.E." The Critic 5 (August 1884): 5-6.

- "Gems from Judah Hallevi." Jewish Messenger, Feb. 14, 1879.

- "The Jewish Problem." The Century, 25 (February 1883), 602-11.

- "A June Night." Lippincott's Magazine 21 (June 1878) 734.

- "Meditation." Jewish Messenger, Feb. 21, 1879.

- "Progress and Poverty." The New York Times (2 October 1881): 3.

- "Russian Christianity versus Modern Judiasm." The Century 24 (May 1882), 48-56.

- "The Sacrifice." Lippincott's Magazine 10 (Aug 1872):162.

Lazarus, Josephine. "Emma Lazarus". The Century 36(October 1888):887. Reprinted in The Poems of Emma Lazarus. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1889.

Letters to Emma Lazarus in the Columbia University Library. Ralph L. Rusk, ed. New York: New York Public Library, 1949.

Lichtenstein, Diane. Writing Their Nations: The Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Women Writers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

——. "Emma Lazarus." Jewish Women In America. Vol. 1. Paula E. Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore, eds. New York : Routledge, 1997. 806-808.

Lippincott's Magazine. 20(1877)

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. The Poetical Works. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1874.

Mordell, Albert. "Some Final Words on Emma Lazarus.'" Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 39 (1950): 321-7.

New-York Historical Society. Old New York in Early Photographs, 1853-1901. Mary Black, ed. New York: Dover Publications, c1976.

Ruchames, Louis. "New Light on the Religious Development of Emma Lazarus." Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 42 (1952): 83-8.

Schappes, Morris U. "Songs of a Semite Back in Print." Jewish Currents (Oct. 1979): 20-1.

"Sensation at Saratoga". The New York Times. June 19, 1877.

Swerdlow, Tess. "The Emmas: Progressive Jewish Women." Jewish Currents (November, 1975): 18-21.

Szold, Henrietta. "Emma Lazarus." Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1904. 7:651-2

Vogel, Dan. Emma Lazarus. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980.

Young, Bette Roth. Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters, Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995

Archival Sources

American Jewish Archives. Cincinnati Campus, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion.

American Jewish Historical Society. New York, NY.

Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. New York, NY.

Collection of the New York Historical Society. New York, NY.

David R. Godine Publishers. Boston, MA.

Emma Lazarus Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. New York, NY.

Houghton Library, Harvard University. Cambridge, MA.

John T. Hopf.

Levick Collection, the Mariners' Museum. Newport News, VA.

Library of Congress. Washington, DC.

Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. New York, NY.

Redwood Library and Athenaeum. Newport, RI.

Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. Cambridge, MA.

Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College. Northampton, MA.

Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library. Charlottesville, VA.

Amazing

Only thing that talks about antisemitism

This is terrible

Most informative article on Emma Lazarus, her literary influence and social activism. Exhaustive bibliography allows for deeper research.

slayed

Maybe add about her struggles?

I personally think it is too long. Please make this page shorter. Thanks!:(

Very intresting

she sounds like an awesome woman