Gertrude Weil

This web exhibit was made possible by the generous gifts of a group of Smith College alumnae.

"It is so obvious that to treat people equally is the right thing to do."

Gertrude Weil's passion for equality and justice shaped the course of her long life. Inspired by Jewish teachings that "justice, mercy, [and] goodness were not to be held in a vacuum, but practiced in our daily lives," Weil stood courageously at the forefront of a wide range of progressive and often controversial causes, including women's suffrage, labor reform and civil rights. She worked tirelessly to extend political, economic and social opportunities to those long denied them.

Weil attempted to better society in countless ways. From the 1910s, when she organized women's suffrage leagues, to the 1960s, when she convened a bi-racial council in her home; from championing child labor legislation to creating parks and pools for underprivileged African-American neighborhoods; from teaching religious school to helping rescue Jewish refugees in the 1930s and 1940s, she expressed her dedication to social justice and social welfare.

A lifelong resident of Goldsboro, NC, Weil was strongly committed to improving the life of her hometown, her state and her region. Although her work certainly had national implications, she focused the greatest part of her attention on Goldsboro and North Carolina. She critiqued her society from within, taking advantage of her position as a prosperous white Southern woman to challenge the racism and sexism that characterized much of Southern culture. As member, advisor, leader or benefactor, she took an active role in every aspect of her town's life. Like many other women across the South and the nation, Weil shaped the political and social culture of her community, helping to make it into a vital and meaningful home for all its inhabitants.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "It is so obvious…." from Frank Warren, "Miss Gertrude Weil," Goldsboro News-Argus, December 6, 1964.

- Quotation beginning "Justice, mercy, goodness…." from Gertrude Weil, "Talk at Beth Or Temple, Sisterhood Sabbath," May 12, 1944, in the Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

A Southern Jewish Childhood

Like most Southern Jews, Gertrude Weil's life revolved around a small-town community, in this case Goldsboro, NC. Her father, Henry, and his brothers had arrived in North Carolina from Germany around the time of the Civil War, while her mother, Mina, grew up in an observant Jewish family in Wilson, NC. By the time of Gertrude's birth on December 11, 1879, the Weils occupied a prominent and influential position in the new but rapidly developing town of Goldsboro.

Although their affluence allowed them to enjoy a privileged white lifestyle—Henry and Mina employed a cook, a housemaid, a nurse, and a "mother's helper"—the family always maintained a sense of responsibility towards the larger community. Indeed, Gertrude made her first foray into public service work at the age of seven, helping her mother at a charity bazaar in aid of victims of an earthquake in Charleston, SC. Highly committed to fostering the political, social, economic and cultural well-being of their town and their state, the extended Weil family taught Gertrude at an early age to value social welfare and civic involvement. Weil was strongly influenced by her mother's and her aunts' many philanthropic and social service activities, as well as by her father's and her uncles' extensive civic and political work.

In 1883, only 17 years after the formation of North Carolina's first Jewish congregation, Gertrude's parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles helped to form Goldsboro's Congregation Oheb Sholom. The Weil family's integration into their town's social and economic life did not diminish their commitment to Judaism and Jewish life. As a girl, Gertrude attended religious school, observed Jewish holidays, and participated in Goldsboro's small but vibrant Jewish community.

Notes:

- Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "The Emerging Political Consciousness of Gertrude Weil: Education and Women's Clubs, 1897–1914," MA thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986, 1–6.

- Margaret Supplee Smith and Emily Herring Wilson, North Carolina Women: Making History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 258–259.

- Moses Rountree, Strangers in the Land: The Story of Jacob Weil's Tribe (Philadelphia: Dorrance & Company, 1969), 86.

Horace Mann

In part because of its large number of German and Jewish immigrants, Goldsboro was ahead of much of North Carolina in the establishment of public education. In 1881, the town opened its first public school, modeled on the advanced German system. As a student, Gertrude wrote for the school newspaper, belonged to the Sigma Phi Literary Club, and participated in the social welfare work of the Ladies' Benevolent Society.

Luckily for Gertrude, Henry and Mina Weil prized education for girls as highly as they did for boys. In 1895, when she was 16, they sent Gertrude to New York City's Horace Mann School, the preparatory high school and teaching laboratory for Columbia Teachers College. Not only was it rare for Southern children—particularly girls—to attend school outside the region, but the co-educational Horace Mann was one of the most progressive high schools in the nation. Its rigorous course of study and the opportunities and examples it provided its female students challenged many of the traditional expectations for late 19th-century women.

Weil made the most of her two years at Horace Mann. The fact that she had close family in New York offered her parents some degree of reassurance, but she roamed the city relatively freely. In addition to studying math, English, science, Latin, Greek, German and drawing, she played sports, listened to lectures, and helped to operate a kindergarten for poor neighborhood children. Her numerous letters home to her "dear ones"—her mother required her to write home at least three times each week—were filled with descriptions of these activities and of the countless museums, plays and concerts she attended. Weil also related her impressions of the rabbis and services of the synagogues she visited regularly.

Notes:

- Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "The Emerging Political Consciousness of Gertrude Weil: Education and Women's Clubs, 1897-1914," MA thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986, 7-8, 11-14.

- Letters from Weil to her family in the Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

Smith College

"Hip! Hip! Hurray!!! Let the joyful news be spread! Gertrude Weil is a member of the class of 1901!" Although higher education for women was still rare in the late 1890s, Weil's high school experiences, her family's support, and her own inquiring mind pushed her to attend college. In 1901, she became North Carolina's first alumna of Smith College.

Smith awakened Weil to a world of new opportunities for women. The strong, independent women she saw around her—professors, fellow students, and those in the Northampton community—defied traditional norms of feminine behavior and gave her an intense respect for women's collective action. Although Weil was constantly warning her parents that she was about to fail an exam or a course, her education taught her how to learn and how to question the political and economic system. Well into her 80s, she would impress her family and friends with her insightful analyses of politics, literature, the arts, and many other subjects.

Smith also reinforced lessons Weil's family had instilled in her. In addition to attending college-sponsored programs on social and political topics, Weil volunteered for Northampton's Home Culture Club, teaching writing to working men and women. A school trip to New York's teeming immigrant neighborhoods brought intense poverty before her own eyes, further intensifying her belief in the importance of social service work. And despite the challenges of being Jewish at Smith, Weil maintained her commitment to Judaism throughout her college years.

Even among women's colleges, Smith was unusual in the late 19th century for the attention it devoted to women's history, economics, and political issues. A series of lectures on the economic status of women and "Schemes of Reform in Women's Wages" were central to Weil's understanding of the relationship between social and economic conditions. By the time she graduated, Weil was an "avowed suffragist," convinced that women's political disabilities lay at the root of a broad range of contemporary problems.

Notes:

- Quotation from letter from Gertrude Weil to her family, September 23, 1897, in the Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

- Additional information from Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "The Emerging Political Consciousness of Gertrude Weil: Education and Women's Clubs, 1897-1914," MA thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986, 20-37; Margaret Supplee Smith and Emily Herring Wilson, North Carolina Women: Making History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 259; and conversation with Emily Weil, April 2001.

Federation Gertie

Following her graduation from Smith, Weil hoped to become a kindergarten teacher, but her mother wanted her home. Bowing to Mina's arguments that she could be of as much service to people in need in a small Southern town as elsewhere, Weil returned to Goldsboro.

Weil immediately became involved with the new Goldsboro Woman's Club, established by her mother in 1899. Part of a growing nationwide movement of women's clubs, the Club educated its members in a variety of subjects, including home economics, health, literature and civics. Club members also worked to foster civic improvement through such projects as traveling libraries, constructing a town pavilion and strengthening relations between parents and local schools.

Clubwork offered Weil an outlet for her social reform impulses, and she threw herself into it with gusto. The committees she chaired were always lively and innovative, and within a few years, she became president of the Goldsboro Club. President again during World War I, she had members study the war's underlying political and social issues while organizing a giant vegetable garden to feed soldiers' families.

Sallie Southall Cotten, founder of the North Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs, quickly recognized Weil's talents. Witty, persuasive and modest, Weil was a popular speaker, and her zeal for clubwork and civic reform soon earned her the nickname "Federation Gertie." Over the years, she served the Federation in numerous capacities. Through her extensive involvement with the organization, Weil honed her leadership skills and gained an intimate knowledge of the political process, assets that would serve her well over her subsequent decades of reform work.

Notes:

- Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "The Emerging Political Consciousness of Gertrude Weil: Education and Women's Clubs, 1897-1914," MA thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986, 52-58.

- Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "Women and the Transformation of American Politics: North Carolina, 1898-1940," Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1995, 28-44.

- Anne Firor Scott, "Gertrude Weil and her Times," unpublished paper delivered at "Women Working For Social Change: The Legacy of Gertrude Weil," Symposium presented by the Women's Studies Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, March 17, 1984, 9-10.

Suffrage

The passion with which Smith students debated the candidates and issues in a mock presidential election in 1900 heightened Weil's consciousness of women's exclusion from the political process. She became convinced that the economic and social problems she encountered through her studies, as well as through her work with the Woman's Club movement, could not be resolved without addressing women's political disabilities. "I wondered why people made speeches in favor of something so obviously right," she later recalled. "Women breathed the same air, got the same education; it was ridiculous, spending so much energy and elocution on something rightfully theirs."

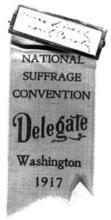

Despite the opposition of her mother and other relatives to women's suffrage, Weil helped found the Goldsboro Equal Suffrage Association in 1914 and served as its first president. By 1917, she was an officer in the North Carolina Equal Suffrage League, becoming president in 1919. The same year, she declined a nomination for the presidency of the North Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs to concentrate on the fight for suffrage.

During the crucial years of 1919 and 1920, Weil navigated the complicated racial and states' rights issues that swirled around suffrage in the South. She was a powerful motivator. Working closely with Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, she gathered thousands of names on petitions, obtained endorsements from prominent North Carolina men and traveled the state to rally supporters. Despite Weil's best efforts, however, the North Carolina legislature failed to lend its support to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

Despite rumors that she would run for office, Weil limited herself to working to improve the political system. In 1920, she established the North Carolina League of Women Voters, dedicated to educating women about the political system and their newly won rights. She also became a leader in the Legislative Council of North Carolina, organized to advance progressive social reforms. In 1922, she made headlines when she destroyed stacks of previously marked ballots intended to be stuffed into ballot boxes to fix an election.

Notes:

- Quotation from Moses Rountree, Strangers in the Land: The Story of Jacob Weil's Tribe (Philadelphia: Dorrance & Company, 1969), 133.

- Additional information from Margaret Supplee Smith and Emily Herring Wilson, North Carolina Women: Making History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 260; Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "Women and the Transformation of American Politics: North Carolina, 1898-1940," Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, 1995, 219, 310; Anne Firor Scott, "Gertrude Weil and her Times," unpublished paper delivered at "Women Working For Social Change: The Legacy of Gertrude Weil," Symposium presented by the Women's Studies Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, March 17, 1984, 10-11.

Labor Reform

Weil's interest in issues of labor reform had deep roots. Not only had her mother fought for child labor legislation, but Weil's own education showed her the dire poverty endured by many working people and convinced her that women's political and economic disabilities were intimately entwined. North Carolina's labor laws, moreover, were extremely weak. In the early 1920s, women could legally work an 11-hour day and a 60-hour week, with supervisors often demanding much more. In opposition to those who argued that protective legislation would put women workers at a disadvantage, Weil believed such laws could protect women from the most exploitative industrial practices.

In 1916, Weil called for a survey of women's working conditions, believing it would be a crucial first step in reforming the worst aspects of industrialization in the state. In the 1920s, the North Carolina League of Women Voters, the Legislative Council of North Carolina Women, and the state Federation of Women's Clubs—in all of which Weil took a leading role—lobbied vigorously for the survey before legislative committees and elsewhere. Their efforts brought them into conflict with powerful North Carolinian industrial and political interests, who likened them to Trotskyite and Leninist radicals, undermining the fabric of the country.

In 1929, female textile workers in North Carolina went on strike to protest long hours, low wages, and poor working conditions. Although manufacturers opposed unionization, the state's women's groups, with Weil in the lead, strongly supported the strikes. In 1930, Weil was a leading participant in a group of progressive citizens who issued a manifesto in support of collective bargaining and free speech; nearly one-third of the manifesto's 439 signatories were women. In 1931, the women's Legislative Council finally won shorter hours for women workers, the prohibition of night work, and other industrial reforms.

Notes:

- Marion Roydhouse, "'Our Responsibilities are for Women': Gertrude Weil and Labor Reform," unpublished paper delivered at "Women Working For Social Change: The Legacy of Gertrude Weil," Symposium presented by the Women's Studies Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, March 17, 1984.

Social Service

"Social welfare—that's the chief interest I have ever had," Weil asserted in 1964. "People are wrong in thinking that the best incentive is competition," she said. "Competition is good, but only as the instrument for the common good." Wishing to prevent poverty, not just alleviate it, Weil emphasized strongly the need to reform basic social structures. Beginning with her philanthropic activities as a child and continuing through her adult work as a volunteer, an activist and a paid professional, she devoted significant amounts of time, effort and money to serving "the common good."

For many years, Weil provided vital assistance to needy families through the Goldsboro Bureau of Social Service. As president in 1927, she directed the Bureau to "look beyond the immediate problem of the special case to the underlying physical and social conditions that lead to dependence and maladjustment"; as chair of the Decisions Committee during the Depression, she made recommendations about how best to help struggling families. In 1933, "because of [her] record of social service and [her] influence in [her] community," Weil was appointed a Director of Federal Public Relief Work, responsible for administering local New Deal relief efforts.

Weil was also a longtime member of the North Carolina Conference for Social Service, founded in 1912 to address some of the state's most urgent social issues. Through the Conference, Weil explored such issues as the juvenile justice system, race relations, social services for the indigent, and the desirability of the laws requiring physical exams before marriage. Work with the organization allowed her to attempt to formulate solutions to treat some of the many social problems she had studied years earlier at Smith.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "Social welfare...." from Frank Warren, "Miss Gertrude Weil," Goldsboro News-Argus, 1964.

- Quotation beginning "People are wrong..." from Margaret Supplee Smith and Emily Herring Wilson, North Carolina Women: Making History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 261.

- Additional information from Sarah Wilkerson-Freeman, "Women and the Transformation of American Politics: North Carolina, 1898-1940," Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, 1995, 168 and the Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

Interracial Cooperation

Long before the boycotts, demonstrations and sit-ins generally associated with the civil rights movement, Weil's dedication to social justice led her to challenge the segregation, disenfranchisement and lynchings that marked the lives of Southern blacks. While she was not alone in her early civil rights work, her consistent efforts to improve race relations took considerable courage in the highly segregated South.

Weil first immersed herself in civil rights work in 1930, participating in the Anti-Lynching Conference of Southern White Women and subsequently joining the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. As a group, these women contested the prevailing argument that lynchings of black men were necessary to protect white women from the supposed sexual threat of black men. Weil and her colleagues insisted they had no desire to be "protected" in this way.

In 1932, Governor O. Max Gardner appointed Weil to the North Carolina Commission on Interracial Cooperation. Composed of white and black leaders, the Commission aimed to foster communication and mutual trust between the two communities. Through the Commission, Weil became involved in some of the most critical race issues of the era, as she advocated legal, economic, political and educational equality for black North Carolinians.

Well into her 80s, Weil championed attempts to integrate schools and other Southern facilities. Long after most white families had left the area, she continued to live in downtown Goldsboro, inviting her black neighbors into her home in defiance of powerful Southern norms. In 1963, she convened a Bi-Racial Council in her home. The same year, when many whites refused to bow to African-American demands that they remove statues of black delivery boys from their lawns, Weil painted hers white to underscore the ridiculousness of the situation.

Notes:

- Episode of delivery boy statues from Frank Warren, "Miss Gertrude Weil," Goldsboro News-Argus, December 6, 1964.

- Additional information from Margaret Supplee Smith and Emily Herring Wilson, North Carolina Women: Making History (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 261, and the Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

What Judaism Means to Me

Weil's commitment to social justice was strongly rooted in her concept of Judaism. She often commented that her religion taught that "justice, mercy, goodness were not to be held in a vacuum, but practiced in our daily lives." Believing Judaism to be "a religion of this world," one that emphasizes the "expression of righteousness in the here and now," she argued that "every...act should be an expression of the God, or goodness, in us." Her work for social reform emerged out of this long Jewish tradition of tikkun olam and prophetic justice.

For decades, Weil was a mainstay of Jewish life in Goldsboro. She taught Sunday School, conducted adult Bible study groups and presided over the Temple Sisterhood. Once, local officials had to reveal that she was the recipient of the town's distinguished citizen's award in order to convince her to attend the ceremonial dinner, held on a Friday evening when she would normally have been at services. As she grew older, Weil became increasingly serious in her own study of Jewish history and religion.

Unlike most Southern Reform Jews, Weil, her mother, and her siblings were strong Zionists. Henrietta Szold, Hadassah's founder, was a personal friend of Mina Weil; Gertrude and Mina were founding members of Goldsboro's Hadassah chapter and Gertrude served as president of both the local and regional groups. She also presided over the North Carolina Association of Jewish Women, sat on the board of the North Carolina Home for the Jewish Aged, worked for the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods, and helped to raise money for numerous Jewish charities. In the 1930s and 1940s, she and her mother devoted much time and effort to rescuing Jewish refugees from persecution in Europe. In her widespread Jewish activities, Weil demonstrated the same energy and active commitment as she did in her work in the broader community.

Notes:

- Quotations from Gertrude Weil, "Talk at Beth Or Temple, Sisterhood Sabbath," May 12, 1944, in Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

- Additional information from Mrs. N.A. Edwards, "In Love with Life," draft of article for American Jewish Times, October 1956, in the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Elna C.G. Grissom, "Jewish Relief and Other Philanthropies of the Weil Family of Goldsboro, North Carolina, 1935-1945," M.A. thesis, Wake Forest University, 1984.

Local Change

As member, advisor, leader or benefactor, Weil took an active role in every facet of her community's life. As the president of Smith College said in awarding her one of the first four Smith College medals in 1964, Weil's "career of public service [was] so extensive that it is difficult to find in the State of North Carolina a cultural, charitable, welfare, civic or educational organization with which [her] name...has not been connected." Her affiliations ranged from the local Woman's Club and Temple Sisterhood, to state suffrage organizations and Jewish groups, to the Art Society and the Literary and Historical Association. In addition to countless private acts of philanthropy, she financed a county nurse before a public health system existed, created parks and pools for underprivileged African-American neighborhoods, provided scholarships for poor students, taught religious school, and worked with Girl Scouts.

Weil's active involvement in the most pressing issues of her day created effective change at the local and state levels. As the Chancellor of the University of North Carolina commented in 1952 when awarding Weil an honorary Doctorate of Human Letters, she was "in the forefront of every forward movement looking toward a progressive social and economic program for North Carolina.... [a]lways generous in the giving of her time, effort and money in the promotion of various enterprises for the good of the city." Like many women in small towns and small Jewish populations, Weil played an integral role in shaping her local society, helping to make it into a vital and meaningful home for all its inhabitants.

Notes:

- Speech given at the awarding of the Smith College Medal, 1964, text in "The Smith Medal," Smith Alumnae Quarterly, November 1964, p. 24.

- Notes for Citation of Gertrude Weil for the honorary degree of Doctor of Human Letters, conferred by the Women's College of the University of North Carolina, June 2, 1952, at the North Carolina Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Legacy

In 1900, Gertrude Weil's mother wrote, "My greatest desire for my children is to feel...that the world will be better for their having lived, not great things but good is what I wish them to do." Gertrude certainly fulfilled her mother's hopes. Drawing upon the family tradition of civic involvement, she became "a woman of deep convictions and fearless in their defense, and one whose honesty and integrity of purpose is never questioned." Her longstanding career as a dedicated "citizen-activist" created significant progressive change.

Weil exerted a powerful influence on all those around her. Her friends and family "just adored her," remembering her for her generosity and compassion and her electric conversation. Community members vied for invitations to her lunch table, at which the latest books and political and social issues were discussed; food was slow in getting around the table because everyone was so engrossed in what Weil had to say. Guests always left wanting to read what she suggested and get involved in the issues discussed. Her interest in each person with whom she spoke was deep and sincere and won her many intensely loyal admirers. Although she never held elective office, Weil had a stronger impact on her community than the vast majority of political officials.

On May 6, 1971, the North Carolina General Assembly ratified the 19th Amendment, for which Weil had worked so hard in 1920. Exactly two weeks later, Weil died in the same house in which she had been born 91 years earlier. Her legacy lives on in all those, in North Carolina and beyond, who continue to take inspiration from her extraordinary commitment to making her world a better, more just, and more inclusive place.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "My greatest desire" from letter from Mina Weil to Gertrude Weil, September 21, 1900, Gertrude Weil Papers at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, cited in Anne Firor Scott, "Gertrude Weil and her Times," unpublished paper delivered at "Women Working For Social Change: The Legacy of Gertrude Weil," Symposium presented by the Women's Studies Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, March 17, 1984, 4.

- Quotation beginning "a woman of deep convictions" from Notes by Edward K. Graham, Chancellor of the University of North Carolina, in the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Additional information from conversation with Emily and David Weil, Goldsboro, NC, April 25, 2001.

Media

Timeline

Born on December 11 in Goldsboro, NC, to Mina (Rosenthal) and Henry Weil

Graduates from Horace Mann High School at Columbia Teachers College in New York

Participates in mock presidential election at Smith College, sparking her interest in the cause of woman's suffrage

Graduates from Smith College, Northampton, MA, becoming North Carolina's first Smith alumna

Joins Goldsboro Woman's Club, later serving three terms as president

Helps establish and becomes president of Goldsboro Equal Suffrage League

Elected First Vice President of North Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs

Begins fight for state-wide survey of women's labor conditions

Becomes president of North Carolina Equal Suffrage League

Founds and serves as first president of North Carolina League of Women Voters

Elected to first of three terms as president of North Carolina Association of Jewish Women

Begins decades of work with North Carolina Conference for Social Service

Becomes president of Goldsboro Bureau of Social Service

Joins North Carolina Commission on Interracial Cooperation, serving on it and its successor organization for over 25 years

Serves as president of Temple Oheb Sholom Sisterhood, Goldsboro

Appointed Director of Federal Public Relief Work for Goldsboro, responsible for administering local New Deal relief efforts

With her mother, begins years of efforts to rescue Jewish refugees from persecution in Europe

Receives honorary doctorate from University of North Carolina-Greensboro

Organizes Bi-Racial Council for City of Goldsboro

Receives Smith College Medal in its first year, "for a lifetime of service to the cultural, charitable, religious and political welfare of her state"

Dies on May 30 at the age of 91, in same house in which she was born

Bibliography

Published Sources

"Miss Gertrude Weil is not a Candidate." Raleigh Times, July 31, 1922.

"Miss Weil Not a Candidate Any Ticket," Raleigh Times, July 31, 1922.

Rountree, Moses. Strangers in the Land: The Story of Jacob Weil's Tribe. Philadelphia: Dorrance & Company, 1969.

Smith, Margaret Supplee and Emily Herring Wilson. North Carolina Women: Making History. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

"The Smith Medal," Smith Alumnae Quarterly, November 1964, 24.

Walker, Harriette Hammer. Busy North Carolina Women. Asheboro, NC, 1931.

Warren, Frank. "Miss Gertrude Weil." Goldsboro News-Argus, December 6, 1964.

Weil, Emily. Temple Oheb Sholom, Goldsboro, North Carolina. Temple Oheb Sholom, 2000.

Unpublished Sources

Antler, Joyce. "Passing the 'Torch of idealism': Gertrude Weil as Southern Jewish Citizen-Activist." Keynote address presented at the 26th Annual Meeting of the Southern Jewish Historical Society, Norfolk, VA, November 1, 2001.

Conversation with Emily Weil, Goldsboro, NC, April 25, 2001.

Conversation with Elmer Oettinger, Chapel Hill, NC, April 27, 2001.

Grissom, Elna C.G. "Jewish Relief and Other Philanthropies of the Weil Family of Goldsboro, North Carolina, 1935-1945," Master's thesis, Wake Forest University, 1984.

Roydhouse, Marion. "'Our Responsibilities are for Women': Gertrude Weil and Labor Reform." Paper presented at "Women Working For Social Change: The Legacy of Gertrude Weil," Symposium presented by the Women's Studies Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, March 17, 1984.

Scott, Anne Firor. "Gertrude Weil and her Times." Paper presented at "Women Working For Social Change: The Legacy of Gertrude Weil," Symposium presented by the Women's Studies Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, March 17, 1984.

Wilkerson-Freeman, Sarah. "The Emerging Political Consciousness of Gertrude Weil: Education and Women's Clubs, 1897-1914." Master's thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986.

——. "Women and the Transformation of American Politics: North Carolina, 1898-1940." Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, 1995.

Archival Sources

North Carolina Office of Archives and History: Gertrude Weil Papers. Extensive correspondence, invitations and announcements, notebooks, souvenirs, diaries, magazine and newspaper clippings, notes, essays, photographs, brochures, telegrams, calendars, etc., relating to the Weil family.

Smith College Archives: Photographs, alumnae information, and records relating to Weil's receipt of the Smith College Medal in 1964.

Love this! Beautifully organized.