Q & A with Artist Giselle Beiguelman

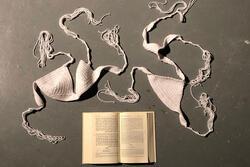

JWA talks to Brazilian artist Giselle Beiguelman about her "Botannica Tirannica" exhibition, which explores how common botanical names both mirror and perpetuate societal prejudices.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JWA: According to the exhibit description, you were inspired to create this exhibition after receiving a plant called the “Wandering Jew” as a gift. What were you feeling in that moment, and when did you know you needed to express those feelings through artistic practice?

Giselle Beiguelman: At that moment [in 2021], I was chilled. This name is a traumatic trigger for many Jews, due to the antisemitic power it possesses. Astonished, I remember arriving home and searching for it on the internet. I couldn't believe it was true that a plant could have this name. But it was. A Google search returned not only various editions of the book Wandering Jew by Eugene Sue, illustrated by Gustave Doré, but also numerous links, in different languages, about this plant (where to buy your Wandering Jew, how to get rid of Wandering Jew, etc.). Disconcerted, I began to research the relationships between botanical taxonomy and nomenclature with antisemitism. It took no more than fifteen minutes to figure out that the problem was broader, encompassing different groups that have been targeted throughout history, like Black people and Indigenous peoples, Romani (derogatorily called "gypsies"), and women.

JWA: Tell us more about the historical and botanical research that went into the creation of “Botannica Tirannica.”

GB: “Botannica Tirannica” involves research in different fields of knowledge. In addition to countless hours of research in herbaria and consultations with repositories and libraries specialized in botany, the research draws on a vast bibliography related to science and colonialism, with special emphasis on the issue of eugenics; botany; arts and artists who operate at the interface between nature and aesthetics; antisemitism; eugenics; and artificial intelligence. The research, especially on plants and their racist, antisemitic, and misogynistic names, is constantly updated. With each new exhibition, I incorporate new perspectives, dialoguing with local prejudices and how they're projected in the popular and scientific nomenclature of plants.

The first expansion of the thematic cores occurred at the end of the first exhibition in São Paulo, with the incorporation of plants associated with the history of homophobia. An entire line of feminist investigation and queer studies is devoted to calling attention to the forms of concealment of these dynamics throughout history. At the same time, these works divest the prejudiced associations between gay people and floral symbolism, giving them new connotations and positivity. Among these terms are the pansy flower, a synonym of "sissy," and the violet, known as the Sapphic flower, or the flower of Sappho.

Other important flowers among LGBTQIA+ symbols are the green carnation of the writer Oscar Wilde and the lavender, whose purple coloring is one of the symbols of LGBTQIA+ movements, but has also been used to exacerbate discrimination since the 1920s. The high point of this anti-gay crusade was Operation Lavender Scare, in the 1950s in the US government, which targeted homosexuals in civil service and led to the mass dismissal of over 5,000 people. In a historic turnaround, in 1969, crowds carried lavender branches in New York in one of the most important marches of the period to affirm the rights of homosexuals, transforming the lavender branch into a symbol of empowerment for these groups.

It was in this direction, in an appropriation of derision and offense to transform it into an agenda for liberation, that I accepted the assignment of “wandering” to Jews as a sign of strength and resilience. In line with some presumptions of contemporary philosophy, I used "wandering" as a derivation of "nomad," which is the social condition that embodies the capacity for change, the deterritorialized body that flows and escapes from the processes of domination.

JWA: You engaged several collaborators on this project, including biologist Jonathan Ferrier, gardener Isaac Crosby, and composer Gabriel Francisco Lemos. Why was it important to you to bring these folks onto the project?

GB: The dialogue with Isaac Crosby and Jonathan Ferrier was crucial in formulating a consistent approach to issues related to Indigenous peoples in Canada, with an emphasis on Ontario. “Botannica Tirannica” was greatly enriched by the ethnobotanical perspectives of both. On the other hand, they repeatedly emphasized that my work illuminated a series of issues that had not yet been considered as themes or problems for them and that have now become intrinsic to their practices. I am a university professor, a researcher-listener. All my work is based on exchanges and sharing of knowledge. The soundscape by Gabriel Francisco Lemos, for example, is not a soundtrack, but the result of a dialogue about my aesthetic methodologies, which, combined with Lemos' individuality, create an immersive environment and a very particular state of suspension in the exhibition space.

JWA: Part of the exhibition includes AI-generated images of hybrid plants, representing a “post-natural, decolonized garden.” How did you decide to include artificial intelligence in the project? What are the benefits of using AI in art?

GB: [AI is used in] photography and audiovisual production to create figures that are more real than real, enabling the substitution of humans by models or actors that do not exist, making politicians say things they never said, or creating revisionist discourses that deny anything from the Holocaust to the lunar landing. These are called “deepfakes,” and they are made using AI that creates new data based on other data, identifying and combining internal patterns while downplaying dissonance. The process of generative imaging, created with AI, is shockingly similar to that which Francis Galton used in his study of eugenics, for which he created a photographic method: composite portraiture. In this process, Galton superimposed different photos and erased their differences to identify the generic criminal or the generic Jew. This is basically what a Generative Neural Network does: it recognizes patterns, in detriment to particularities. But what about things that fall outside the pattern? This is the question behind the post-natural garden.

In my recent work, I use AI to create images that break traditional norms. I fed the system data from plants with names [that are] offensive to various marginalized groups, forcing it to generate new, non-realistic images. This led to my series “Flora Rebellis,” which features videos showing AI processing vast datasets and creating patterns from them. This project helped me understand AI's latent space, where data interactions occur beyond human visibility. Through this process, I realized the importance of learning from machines and bridging the gap between nature and culture, inspired by Donna Haraway's cyborg manifesto. This understanding was pivotal for my series “Flora Mutandis,” where I categorized plants based on personal criteria, creating unique classifications that reflect my artistic vision.

JWA: “Botannica Tirannica” has been shown in museums in Brazil, Pakistan, and Italy, before traveling to its first North American host, Koffler Arts in Toronto. What have some of the international responses to the exhibition been?

GB: “Botannica Tirannica” has had a strong impact on the public and the media everywhere it has been exhibited. People are surprised by the combination of real and fictional plants, and this is a consistent reaction. However, the most common reaction is the shock people feel when they realize how they have naturalized prejudice, using names like “Wandering Jew” without ever feeling any discomfort, or being unaware of the colonial weight and histories of oppression that our national symbols carry.

Brazil prides itself on being the only country in the world named after a plant, [but] this obscures the fact that Pau-Brasil (Brazilwood) was the first product expropriated by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century. By renaming this plant, they performed a typical colonizer's gesture of erasing the histories of the original inhabitants. The plant, in Tupi, one of the Indigenous languages, is called “ibirapitanga” (red wood). The same happens in Canada, which has its beautiful flag illustrated with a leaf from [the maple tree], a tree of great significance to the local Indigenous peoples. Upon being conquered, they saw not only their culture expropriated, but also turned into a symbol of the colonizer's power: the nation. Many plants of great cultural, religious, and social significance to the Indigenous peoples of Canada also have scientific names with “canadensis,” which reiterates the logic of expropriation and one of the statements of the exhibition: taxonomy is a technology of power, and nomenclature (especially scientific) is a ritual of erasure.

JWA: What do you hope viewers take away from the exhibit?

GB: Visitors always bring new contributions to the project, prompting me to research new points and directions. I ask: Please do not hesitate to question me! But yes, I hope everyone leaves this experience with more doubts than certainties. The strength of colonialism lies in how it intertwines with our imagination. The little attention we give to the plant world, treating it as inert and reducing it to a mere supplier of food and ornaments for our gardens, reflects the separation between culture and nature (the latter taken as something to be conquered and dominated) operated by colonialist anthropocentrism itself. We need to open ourselves to other intelligences (plant, animal, and machine), to think in multiple ways. The environmental catastrophe is evidence of the disastrous operation that configured the opposition between nature and culture.

JWA: The subject matter of “Botannica Tirannica” is woven in with your identity and the identities of your collaborators. How do you manage that vulnerability?

GB: This aspect, in relation to the collaborators, was more concretely realized in the working experience with Isaac Crosby and Jonathan Ferrier. We [Isaac Crosby, Jonathan Ferrier, and I] were three people with life stories marked by traumatic pasts and presents because of who we are. I am Jewish, Isaac is Black and Indigenous, and Jonathan Ferrier carries the memory of the bloody past of the Ojibwe People. Both [Isaac and Jonathan] are Canadians. We had moments of great empathy, happiness, and enlightenment, but also many moments of shared pain, confronting our pasts and our presents.

"Botannica Tirannica" can be seen at Koffler Arts in Toronto until October 20, 2024.