Q & A with Author Jennifer Lang

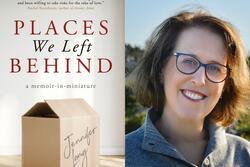

For most authors, completing one memoir would be a life’s work. During years of writing, revision, and soul-searching, Jennifer Lang, the California-born founder of Israel Writers Studio in Tel Aviv and a serious yoga student and teacher, realized she needed two separate memoirs to explore distinct parts of her journey towards accepting Israel as her home. I read both, and am hoping for a third, as life in Israel continues to change. Lang’s unconventional, sharp, and funny storytelling offers an individual frame and an honest lived experience amid the barrage of headlines.

The memoirs were written initially as one, covering Lang’s years of struggle over where to live with her husband, who preferred Israel, and their three children, who Lang felt more comfortable raising in the United States. Lang set the larger work aside when she realized she had a “huge overwritten manuscript” that spent too many pages on her marital conflicts over where to live and how to practice Judaism. She began writing her story anew, focusing on the heart of her personal journey. The result was Landed: A yogi’s memoir in pieces & poses, about her seven-year search, on and off the yoga mat, to find peace and home in the Middle East. The book was published on October 15. During the submission process for Landed, Lang reshaped the earlier chapters/years into a second, separate memoir, which was published first.

Jodie Sadowsky: Your micro-memoir, Places We Left Behind: a memoir-in-miniature was released a month before the atrocities of October 7. What was it like to be on tour last fall for a book about coming to terms with moving to Israel?

Jennifer Lang: The irony was great. On October 2, I was at my childhood synagogue in Northern California speaking about my book, and five days later, my entire life changed. My husband was in Israel, and I couldn’t reach him because it was Shabbat; his phone was off until sundown.

My next event was canceled, but I attended a solidarity event on October 8 at Congregation Sherith Israel in San Francisco. Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi spoke, as well as other elected officials and several rabbis. The temple was so full I needed to sit in the balcony, overlooking the gorgeous stained glass windows. My 26-year-old daughter who has settled in NYC was with me. She was so stoic. We held hands, and I kept telling her not to hold it in. To my right, I spotted a young man bent over, sobbing and shaking. I couldn’t stay seated, approached, asking if I could sit in the empty seat next to him. He nodded. I sat and rubbed his back, like I would do for my own son. We didn’t speak, but I had a whole storyline going in my head; maybe he was Israeli, maybe he had family he couldn’t reach on a kibbutz.

When we rose for Hatikvah, I collapsed into my chair, sobbing and shaking. This stranger sat and rubbed my back. After seeing him lean into the man next to him and their matching wedding rings, I felt relieved he wasn’t alone and wordlessly returned to my seat.

On October 9, as planned, I headed to New York for events: libraries, bookstores, writing classes, book groups. I chucked the prepared script and spoke from the heart. We sat in circles, and people shared their connections to Israel, about their children on gap year programs or in the IDF. We cried on and off together. That’s how those early days were.

JS: When did you return to Israel and what was it like?

JL: My husband knew how hard I’d worked planning my book tour and didn’t ask me to change my plans. I returned, as scheduled, in late October, steeling myself for war. In the car en route from the airport, I asked my husband what we’d do if there was a siren and, as usual, he pooh-poohed me; minutes later, a siren. Everyone stopped. It was my first time [hearing a siren] on the road, in the open, so vulnerable. He reassured me that staying put under the overpass was safer than crouching near the highway barriers. My right leg dangled outside, my left in the car, like a standing straddle pose in yoga. Fear gripped me. There was an enormous emotional gap between me and family and friends who’d been in Israel since October 7, and it took me several weeks to close it.

JS: You are a self-proclaimed “structure geek.” How did you arrange the complex parts of your story in Landed?

The book takes place over a seven-year period, from 2011 to 2018, in the present, past, and [yoga] poses. The yoga poses and my narrative are in the present tense, but I jump back in time thematically, using the past tense, indicating the year and place. For example, when I’m discussing our marital religious issues, I harken back to my Reform Jewish upbringing. Like a fisherwoman, I kept reeling back, tightening the rod to focus my story on certain points.

The book is divided into seven long chapters, each separated by a story of me learning the seven chakras, starting from the first/root and working to the top. In a way, this structure mirrors the “enlightenment” I was reaching (except I'm still searching for enlightenment); with each year, my resistance to living in Israel and my growth to accept my obstacles and change was getting clearer and clearer.

JS: Yours is not simply a story about adjusting to the sirens and threats and your kids being drafted in the IDF. There is much inner, personal growth to admire, as you write, “Sometimes marriage is so hard. Marriage in midlife is even harder. Maturing and seeing one’s own shortcomings: the worst.”

JL: I feel strongly that all memoirists must turn the camera on themselves as much as possible. It took many years of writing and iterations of the story to admit I’m at fault, too. In the moment, it was impossible to step back and own my part. A lot of my impetus to reflect on my role was watching my parents' marriage fall apart. As I got older, I understood the need to take responsibility for the decisions we’d made, to prevent the same from happening to my marriage, to change.

JS: In Landed, you write about a friend who asked whether you felt how “the shared history and communal loss binds you” to Israel, even if you didn’t love everything about the country. In response, you nodded and wondered if one day, you would “share that sensibility: understand that connection of being firmly rooted to Israel.” Did that happen after October 7?

JL: Since the 7th, it’s clear now that Israel is home, that I can't live with all of this history and this experience elsewhere. I used to feel so proud of my Northern Californian roots, but now I feel cautious.

JAS: Some of your reflections in Landed are ominous, almost prophetic of what was to come, or of history painfully repeating itself. In a section about 2014, you wrote, “Nobody believes this ceasefire will stick. Nobody supports the government leaving Gaza with suspected tunnels of terror underneath us.” In another chapter, you wrote, “This region remains trapped in its own Catch-22: neither side capable of nor willing to refrain from violence and embrace peace, forever entwined in a game of tit-for-tat.” What changes did you make to the text after October 7?

JL: By the winter of 2023, I was doubting the book, worried I was/am setting Landed—and myself—up for failure. Nina Lichtenstein, my very wise writing friend, helped me see Landed like a first or false landing, when, in fact, I really landed after October 7.

I had trouble connecting with the narrator in those early years. She seemed whiny and immature. Compared to what happened on October 7, she’d endured nothing. The wimp of wimps. I spent weeks reading and once again revisioning the manuscript through this new lens to address/incorporate October 7, adding notes in a few very select places to highlight how I felt about what I had written all those years ago.

JS: There’s a scene in the book where Ayat, your Muslim, Arab-Israeli yoga student, gives you the words to describe where you live and who you are: “Hard, but beautiful.” For you, what are the hardest and most beautiful parts of your life in Israel?

JL: The beautiful part that was in front of me all along: my husband, our children, our home in the center of Tel Aviv. I feel lucky to be here. For me, it’s been about changing my reference point. I stopped being the California girl.

On the hard side: it’s in the book. How’s that for a teaser?

Watching the world unravel is painful and lonely. A dear American friend explained it perfectly: Israelis are used to being hated. For them, this isn't new. Even for Europeans, antisemitism is not new. But for me, for us, being loathed and demonized and cut off (think American Airlines stopping flights to Israel) makes me lose sleep. A profound, visceral sadness that will take years—decades—to shed.

That said, I’ve felt moments of hope. In December, my daughters and I drove to FeelBeit, an Arab Cultural Center on the edge of West Jerusalem, to hear the Jerusalem Youth Chorus perform. They're a choral and dialogue program for Palestinian and Israeli high schoolers, who recently appeared on America's Got Talent. They sing in three languages: Hebrew, Arabic, and English. The room was full of people, who probably, like me, found it hard to be there but knew it was important. We came in hesitant and left on a high. It gives me hope that people in both places can sit in a room together, listen to music, and hope.