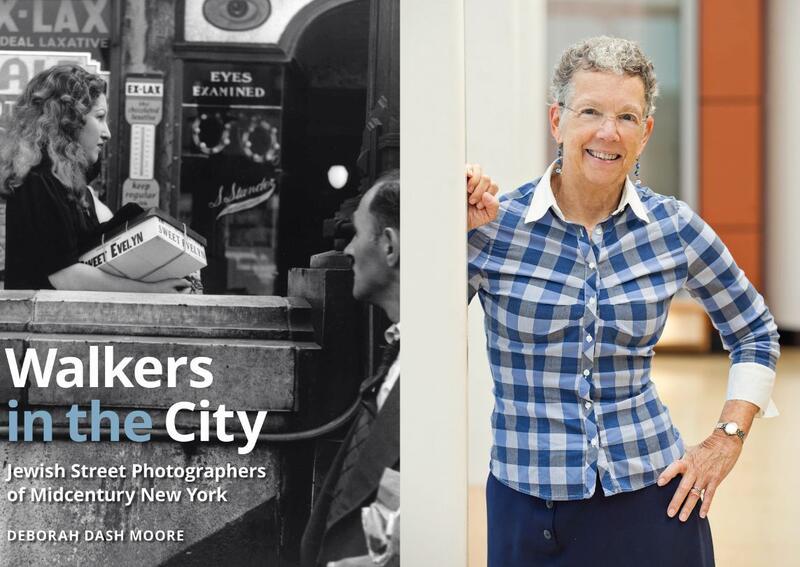

Q & A with Deborah Dash Moore about her New Book, "Walkers in the City"

Photographer Anne Vetter talks with Deborah Dash Moore about her new book, Walkers in the City: Jewish Street Photographers of Midcentury New York. The book recently received a National Jewish Book Award.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Anne Vetter: Even as someone who knows photo history, I learned so much through this book. There was so much that I just had not considered. And I think one of the things that really stuck out to me, that I guess I knew, but I had never put words to, is the idea that documentary [photography] at the time was leftist and that was just kind of a part of it. And I was really interested in the tension that's kind of throughout the book, of the photographers being, like, “We're not doing this because we're Jewish. We're doing this because we're leftists.”

Something that I was really interested in also was how, even though there's this denial, denial, denial [that] the work is about Jewishness, that Jewishness gives the photographers this really specific point of view where they're visually unmarked enough to move through spaces and have power, but also have the experiences of being minorities and of being marginalized. And so that they're attuned to and asking questions that maybe other photographers of similar visual dispositions wouldn't think to ask, places they wouldn't think to look.

Deborah Dash Moore: Yes, the whole business about being visually unmarked, I think, is really crucial. Although you do have to recognize that in the New York of '30s, '40s [and] '50s, um, most New Yorkers could look at people who we would classify today as white [and] figure out exactly their ethnicity. This one's Irish. This one's Jewish. I mean, they just—they knew how to decode what later scholars talk about [as] a kind of uniform whiteness.

AV: Yes. And that's interesting, when you talk about that in the prewar era versus the postwar era, where there became this really rapid ushering in of Jews into whiteness And that shift through the book is really interesting.

But I want to go back to the idea of Jewishness and leftist identity. One of my favorite quotes in the book was a George Gilbert quote that says, “I realized the camera was a tool for convincing people there had to be a better way to live.” And I'm really curious about what you see as the connection between Jewishness and these photographers and leftist politics.

DDM: The Gilbert quote, I think, is really important, because it relates to how these photographers saw what they were doing and the relationships that they established with the people they were photographing. And that's important. In the '30s, prior to World War II, there were these collective projects, right? It wasn't just about individual expression and whatnot. It was collective. And they sort of mapped out how you photograph a neighborhood, but then you want the people to see the photographs. And you want them to come to—in seeing themselves, as it were, or their neighborhood through the eyes of photographers, you want to give them the power to make changes. Most of the time, we go through life and we don't really see what we're doing. There was a belief that photography could let you see, and by seeing the world, you could become empowered to change the world.

Which is why, among the things that they don't show, is they don't show “bums”—they're not interested in the down and out. There's not this sort of exotic otherness that they're taking pictures of. These are people like them. And so there's an empathetic relationship. And those photographs are exemplary of that.

Lou Bernstein, Father and Child, 1943. 2005 loubernsteinlegacy.com. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Irwin Bernstein, irwinbernstein@bellsouth.net

AV: Yes, absolutely. There's two photos in particular that I'm thinking of. One is of the Black children at the pool. I think that's in the chapter “Looking.” And then in the chapter “Letting Go,” there's the photo of the Black father. It's taken from above and he has his child on his chest. And it's just this really beautiful photo. And I think that, yeah, there is really this egalitarian way of looking that I see, in so many of these photographs, of the photographer wanting to see themselves reflected back and wanting to see their own humanity reflected back.

And I think that that is such a Jewish thing, of being like, I want you to see me as whole. Because Jews had experienced this thing of like, you're just going to be looked at as a Jew, or you're going to be looked at as an other and then being like, “No, like, this is where I am. I'm an American. This is where I live. This is where I'm from.” Especially these Jews who were born in America, even if their parents were immigrants. And you write about this. This is them making their sense of identity, claiming themselves as Americans, but more than Americans, as New Yorkers.

DDM: Yeah. So the Lou Bernstein photo of the father, you know, in the sand, looking out with the girl, I think that's the one you're referring to, right? You feel that, in how he pictures his neighbors, and in this case, how he pictures the father and child…He only got a camera when his first child was born. So I think he was particularly attuned to the father-child relationship.

AV: One of the things that I was really interested in, as we talk about looking, is that progression from these unaffected people being like, The photos have to be just as you see them, they can't really have an artistic point of view, towards these more really beautifully composed, really artistically shot photos that are still within the realm of street photography. And I think that no one today would struggle to see these as documentary photos, but they really were quite a progression away. I'd be really curious to hear you talk more about that shift and then also the tension that existed within these communities around how [you] should compose a photograph.

DDM: Right. So Sid Grossman is a good example of that, because he does take the photo of the kids in the Harlem swimming pool. And then he crops it. I show both the original with the blurred figure, um, entering into the frame, and and the crop, which turns it into a vertical photo and catches the kids really looking at him in a sense, looking back. And the lines of, the cement steps that they're stretched out on relates more to the Sid Grossman who, emerges after World War II, as someone who sees the expressive potentials of photography, the personal expressive, where his politics—he'd been a Communist and he lets it go in the postwar years, and instead is drawn very much to the ways in which photography can engage with these wonderful expressions, both of the people being pictured, but also how he felt. He's an example of these shifting attitudes that occur after the war, where the possibilities of documentary photography, come to include this more expressive, personal form.

AV: Yes. I think that if you have a marginalized identity, people immediately make your work about identity and they immediately say that it's subjective. Which is something that I come across as a queer photographer, a nonbinary photographer, a Jewish photographer, where like, of course, I'm making work about identity because I'm not normative in these ways. But everyone is making work about identity, whether or not you are saying that it is, in the same way that all of this work was incredibly self-reflexive. It was always about what is this person interested in looking at? Even if you're not choosing how to frame, you're still choosing to look, you're still choosing to be there and press the shutter. It's always an act of reflection of who you are and what you're interested in looking at.

You do say something about this in the book, about how photographs are as much made in the edit and in the crop as they are when you're out in the camera. It's like this choice-making that eventually creates this narrative that feels like truth. Photography, more than any other medium, has a way of making viewers believe that it is true. It's such a powerful medium. And I can see how powerful it was for these Jewish photographers as a source of laying their claim over identity and laying their claim over a point of view that really has—you look back at these photos, these photos shaped street photography in the United States.

DDM: Oh, yes. I think that's definitely true. I'm so glad you're a photographer, because I haven't talked about this with other photographers, that the choices that get made each time are really important.

And at the same time, you recognize these are very young people. These are teenagers. And so it's also, you know, they're not fully formed adults, as it were, yet. The sense of discovery that occurred through these photographs…Engel's photographs that he takes as a teenager are just great, you know, that you really feel what he's like as a young man trying to figure things out, in part, through the photography.

AV: And it was such a time where finally having a form of expression that was accessible…You talk about how the camera was this really accessible thing. Wasn't it a nickel to use the dark room or something?

DDM: You had to pay ten cents for the chemicals.

AV: Yeah. That was amazing, that people could just come in and create in a way that was just impossible before. And so you have this really interesting overlap between a changing America, these children of Jewish immigrants coming in, having to figure out, what does it mean to be a Jewish American? And then also, you give them all a bunch of cameras. Like, what an amazing time for Jewish history and also for photo history.

I also would love to talk about—the book really delves into race politics, class politics, and gender politics, and one of the things I was so interested in was talking about how the camera became a form of permission for women photographers in the Photo League to look at things and to go places that maybe—that no, definitely they would not be able to have done without. And I'm really curious to talk about the camera as a form of permission.

DDM: So, yeah, I use the phrase, “The camera gives you a license to stare.” [That was] especially true for women who—one has to remind people today— how constrained women were on the streets of the city. They went out, of course, by themselves. But there were real constraints on, um, where they could go and how they had to be dressed and, you know, how they had to walk the streets, which is why, of course, the cover image, the Engel “Sweet Evelyn” is so great, because of the way it lets you see this woman navigating the streets of the city, even as she's surely aware that this man is looking at her.

But once a woman could get a camera, then indeed, she could go places and she could look at things that she wasn't really able to look at otherwise. Because the camera gave her that kind of license, and she could take on assignments that introduced her to worlds that would otherwise have been closed to her.

As a photographer, the streets, because the streets were filled with kids, [were] a place where women felt pretty comfortable, relatively speaking, and they could, uh, because the kids ignored them, they could take a lot of photographs of children. So Helen Levitt's, uh, studies of children are really wonderful. Someone like, uh, Rebecca Lepkoff, you know, hung around her own neighborhood a lot, the Lower East Side, to take pictures there.

And again, children are a relatively easy thing to do, but the more you hang around, the more people sort of ignore. You know, you'd be in the street, and so the fact, then, that you have the camera is something that they get used to. And as I mentioned, many of these photographers interacted with the people with whom they took photographs, and therefore gave them copies of the photographs. That was part of the deal, you know? Most people did not have cameras, you know, it's the complete opposite of what it is today, everybody has a phone with a camera. Attitudes towards cameras, therefore, were different. So I think that the gender dimensions were really important.

AV: I was reflecting on how it's not just, like, the permission behind the camera, but the photographers are really witnessing the permission in front of the camera, of the differences between where men and women can go and be. There's a photo at the end of that chapter, the Levinstein photo, [of] the three men looking at one woman that is, I think, one of the most interesting photos in the book. And you write about how he's witnessing these men looking, but also he's reflecting back his own sense of voyeurism. I'd be really curious to hear you expand more on that photograph.

DDM: All right, so the Levinstein photograph—yeah, he comes to photography not as a teenager, [but] later, after World War II, um, and photography is for him an opportunity to be a voyeur, and he's really conscious of that, how he sees people, and in the process of taking their picture, they become his. So the voyeurism, uh, for Levenstein becomes this means to create for him an ersatz family, as it were, right?

AV: Is there anything else you would like to share about this book?

DDM: So I think, you know, readers would be really interested in discovering some of the women photographers, most of whom, you know, they may have a book or two, but they're really not well-known, and they're wonderful photographers. Some of them are in the encyclopedia [at the end of the book]. I don't think Vivian Cherry is, and she's a great—she's a political one and you can see it in, um, the photographs of the kids playing games of lynching.

AV: Oh my God. Those were wild.

DDM: . Yeah. Yeah, the press was actually very nervous about publishing that.

AV: Didn't Time not want to include—

DDM: Oh yeah. That's correct. They rejected it because they said, what was the redeeming quality about it? It's like, excuse me!

AV: Because it shows that the children are aware of these things!

DDM: That's right. Yes.

AV: They are embodying it and having to process it through play. It's so political.

DDM: It's very political. That's correct. Yes. So she's a great photographer that I think people should check out. I think more broadly that photography has allowed women to find modes of self-expression, which are really important, and that they should be aware of it.

At the same time, I'm well aware that many of the women photographers in the book—with the exception of someone like Helen Levitt, who never married—that when they married and had kids, they stopped taking pictures for a long time. It was just too hard. As a photographer, you go out in the daytime, you take your photos, but then you spend your nights, you know, developing in a darkroom, you know, and printing. We're in an age when people are not aware of the fact that when you took pictures back then, you didn't know what you had. Because everybody's so used to taking a picture and then looking at it and saying, “Oh yeah, I like that. I don't like it.” [Back then] you didn't know. And that's important also to remember in terms of the creative process, of what was involved.