What Queen Esther can teach us about intermarriage

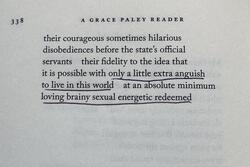

“She was trying as hard as she could not to be beautiful. But she had a brightness on her, made stronger by the fact that she wanted to hide it; thinking if it was seen, somehow, it would make him choose her, and of course it did.”

I wrote this about the Persian Queen Esther just before Purim, the year my son’s father and I got divorced. When Esther first married the PersianKing Ahaseurus, he did not know she was Jewish. By the time he discovered her faith he didn’t care, having fallen in love with a brightness that could only have come from his queen’s willingness to meet life head on.

I am at a Purim celebration on Grand Avenue, thinking of Esther. My son Josh is dancing with other children and then settles to watch a Purim play. My friend Melody sits next to me, having brought her daughter, who is Josh’s age. “I always feel bad on Jewish holidays,” she says.

“What do you mean?” I ask.

“Because I didn’t marry someone Jewish.”

Of course, I think. This is the story of our generation, of those who married outside the Jewish faith. When I was growing up it wasn’t quite forbidden, but close. There were hushed conversations my mother had about this or that one who fell in love with a Catholic—in my youth they were always Catholic—and the heartbreaking dilemma faced by the couple, especially the Jewish half.

Some families sat shiva over intermarried sons and daughters, mourning them as though they were dead. Others gossiped about couples of differing faiths, calling the women “shiksas.” But it would be unfair to say that Jewish misgivings about intermarriage are restricted to older generations. There is still a very real atmosphere of discomfort for people who choose to “marry out,” as the saying goes. I found it in my former spouse’s synagogue, where a congregant said Jews who marry Christians “are finishing what Hitler started” because they are destroying Judaism for future generations.

Okay, she gets no points for the Hitler analogy. But I do see how intermarriage can result in a watering-down of the culture, where a couple’s children might end up knowing little or nothing about Judaism. Because our religion is matrilineal, Jewish women may have it easier in terms of whether their children are considered Jews in rabbinic law. This is not the case for Jewish men, who sometimes ask their brides to convert. I have to say, though, that doesn’t always work out so well, either.

So no matter how you slice it, intermarriage is still a prickly subject. I know writers like Philip Roth have a lot of fun with the ideas I’m raising here, but for people in orthodox and conservative Jewish communities, the stigma remains.

It had been almost two years since I separated from Josh’s father, about eight months since the divorce became final. Now, like my friend, I was seeing someone who wasn’t Jewish, though it had not been my intention to “get involved.” In fact I had tried hard not to—as Esther did, centuries ago. Perhaps she and I had something in common.

Read the rest at TC Jewfolk