Facing Holofernes: How to Live Up to a Name Like Judith

I used to hate my name. I thought it was “an old lady name” (no matter how many times my mom told me otherwise). It didn’t help that I rarely met another Judith who was under the age of 60.

I had friends whose Hebrew names translated to “Lion,” “Life,” “Dove,” “Happiness,” and “Hope.” My name translated to “Jewish Girl.” I was a Jewish girl in real life, and I wanted a name that represented something different.

But as I grew older, I began to understand that names are a huge source of power in Judaism. Consider Sarah, the original Jewish matriarch, who changed her name to prove her devotion to Judaism. This wasn’t merely a name change, but an unbreakable vow to God and her faith. When a Jewish person is critically ill, they may change their name in order to alter their fate. The Hebrew word for “soul,” neshamah, and “name,” shem, share two central letters—one’s name is inextricably linked to their soul.

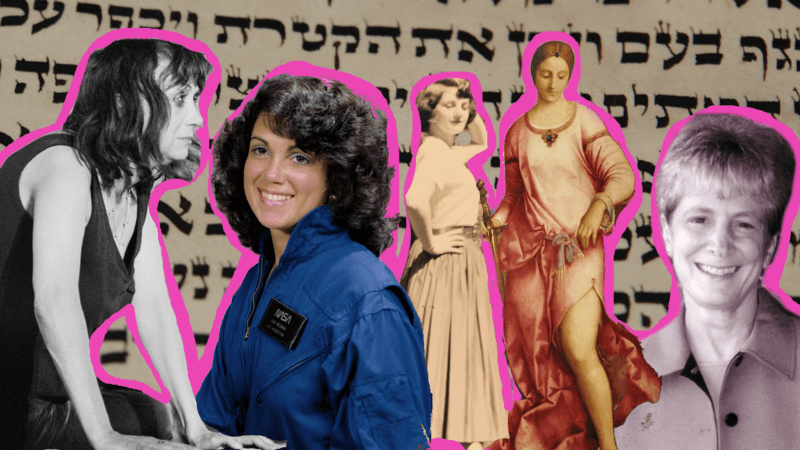

It was only after learning about all of the Judiths who came before me that I really fell in love with my name, and it all started with the original Judith of ancient times. The stakes for the first Judith could not have been higher: she faced a bloodthirsty and powerful Assyrian army that sought to wipe out the Jewish people. Frustratingly, her small town of Bethulia planned to surrender to the opposing general, Holofernes, in five days. Against all odds, Judith and her maid left Bethulia and went into the belly of the beast—Holofernes’s camp. Judith seduced him, got him drunk, and beheaded him with his own sword. The severed head of Holofernes inspired the Jews to launch a surprise attack on the Assyrians, driving them out of Bethulia. If the Jews hadn’t attacked, the Assyrian army would have plowed through Bethulia all the way to Jerusalem, enslaving and converting every Jew they crossed.

Judith’s tale serves as a call to action for every Judith who has come after her. She reminds me not just to recognize injustice in the world, but to actively seek out ways to eradicate it, come hell or high water. When I hear her story, I’m reminded not to let myself be complicit (although that may not translate into me beheading someone).

Another in this mosaic of Judiths is the revolutionary pacifist and actress Judith Malina. Rising tides of German antisemitism forced Malina’s family to flee Germany when she was very young. She grew up to co-found a radical political theater troupe that pushed the boundaries of contemporary theater. Instead of letting the experiences of antisemitism she faced overtake her, Malina weaponized her anger and turned it into stunning, unprecedented pieces of theater that broke every rule in the book.

Judith Resnik was the first Jewish American woman to go to space. As soon as she heard NASA was recruiting women and minorities, she jumped at the chance to put her love for science to good use. But before 1977, she hadn’t shown any interest in the space program. Perhaps the social changes and rise of feminist activism taking place in the U.S. inspired her; perhaps she was motivated by a yearning to explore the unknown. I may never know exactly what convinced Resnik to go to space; she died tragically in the 1986 Challenger explosion. But now, every time I learn about the stars and the planets, I think of her, and her curiosity and bravery inspires me in my own academic journey.

Judiths are not just pioneers in biblical stories, political theater, and astronomy, but have also made their mark in the field of theology. Judith Plaskow grew tired of seeing Jewish theology so heavily influenced by the patriarchy. So, she created a groundbreaking system of Jewish religious thought based on feminist theory. Instead of trying to fix the patriarchal hegemony over Jewish law, Plaskow preached that women should start from scratch and interpret Jewish law themselves. Her work was revolutionary, and completely changed the study of Jewish theology. And to think, when she first started publishing her work, she was going up against a 2,000-year-old patriarchal system. In the face of immense adversity, Plaskow’s work has thrived.

The last Judith I want to talk about is my grandmother. She’s not as well known as Malina, Resnik, and Plaskow. In fact, I actually know very little about her. I don’t know what her voice sounded like, or even what she looked like. I’ve managed to scrape together bits and pieces of information about her. I know she loved Bruce Springsteen and Meat Loaf (the band, not the food). I know she had her pilot’s license. I know she loved the song “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor. I also know that my grandmother faced difficult odds.

The original Judith battled a massive Assyrian army. My grandmother faced a myriad of health problems beginning at birth. I know that she had to still her vocal chords, and that her joy—teaching—was ripped away from her when this happened. I know she could only speak in a raspy whisper for the remainder of her life. And although she was fighting a rapidly decaying body, I think that her greatest battle was against her male doctors and spouses. My mom always says that she was too smart for them, and she’s right; the male-dominated world wasn’t ready for my grandmother. The doctors who kept secrets from her and misprescribed her medication, the men who abused her and tried to keep her down—these were Judith Koren’s Holofernes. Despite everything in the world weighing down on her shoulders, my grandmother soared. I wouldn’t want to be named after anyone else.

There are 2,140,274 Judiths in the world. We are students, anarchists, astronauts, scholars, pacifists, writers, pilots, warriors, grandmothers, daughters, and mothers. All of us have our own personal Holofernes that haunts us: he rears his ugly head in every oppressive institution that exists today. In order to live up to a name like Judith, we must lift up our swords—whether it be a pen, a camera, a megaphone, or a spaceship—and face Holoferneses head on.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

great article! great name! thank you for the encouragement.

My friend sent me this article. I LOVED it. Thank you so much for writing it. Your first paragraph is exactly what I always say about our name. HA!

This is beautifully written. It makes me want to look into my name, which like you when I was young, I did not care for