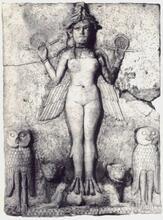

Judith Plaskow

The first Jewish feminist to identify herself as a theologian, Judith Plaskow has created a distinctively Jewish theology that is at once academically rigorous, politically leftist and firmly woman-centered. The best known Jewish feminist theologian in both Jewish and non-Jewish circles, she appears here in 2004.

Photographer: Martha Ackelsberg

Institution: Judith Plaskow

The first Jewish feminist to identify herself as a theologian, Judith Plaskow created a distinctively Jewish theology acutely conscious of its own structure and categories and in dialogue with the feminist theologians of other religions. Plaskow received a classical Reform religious education, emphasizing the universalism of ethical monotheism and the liberal vision of social justice attributed to the prophets. Introduced to feminism while a student in religious studies at the Yale Graduate School, she quickly applied it to her dissertation and to institution-building. Her feminist theology has had a profound effect on Jewish women’s theological conversations in every decade since the 1970s. She is currently in her fifth decade of producing courageous, innovative, and broadly conceived feminist theology.

Judith Plaskow is the first Jewish feminist theologian to identify herself as a theologian. Deeply learned in classical and modern Christian theology yet deeply committed to her own Judaism, Plaskow created a distinctively Jewish theology acutely conscious of its own structure and categories and in dialogue with the feminist theologies of other religions. In shaping this theology, at once academically rigorous, politically leftist, and firmly woman-centered, Plaskow has distinguished herself as one of the most significant constructive theologians of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Family and Education

Judith Plaskow was born in Brooklyn March 14, 1947, to Vivian Cohen Plaskow (1920-1979) and Jerome Plaskow (1918-2002). Her mother was a remedial reading teacher, her father a Certified Public Accountant. The couple had another daughter, Harriet (b. 1950). The Plaskows moved to Long Island, New York, where Judith grew up during the 1950s. Her religious education was classical Reform, emphasizing the universalism of ethical monotheism, the Jewish mission to be “a light unto the nations,” and the liberal vision of social justice attributed to the prophets. “I fully embraced this version of Judaism,” she reports, “without worrying about either its internal coherence or whether it really distinguished us from anyone around us” (Plaskow 2005). Her first theological questions as a teenager—about good and evil, the nature of God, and the nature of human beings—were provoked by studying the Holocaust. As a sixteen-year-old she attended the 1963 March on Washington with others from her congregation and heard Martin Luther King deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech. The vision of a world transformed by racial equality becomes in Plaskow’s work a vision of a world transformed by the full and equal status and contributions of women.

Plaskow received her B.A. from Clark University, magna cum laude, in 1968, and did her graduate work at Yale Graduate School, where in 1975 she produced a doctoral thesis later published as Sex, Sin, and Grace: Women’s Experience and the Theologies of Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. Plaskow observes, “I got a doctorate in Protestant theology because there was no place to study Jewish theology in the late '60s and I wanted to be a theologian.”

Introduction to Feminism

At Yale, Plaskow received her introduction to feminism as a member of the Yale Women’s Alliance. She quickly applied feminism, not only to her dissertation but also to institution-building. She was co-chair of the fledgling Women and Religion Group of the American Academy of Religion from 1972 to 1974 and a member of its steering committee once it became regularized as the Women and Religion Section. In 1981, she co-founded the pioneering Jewish feminist group B’not Esh. She was also co-founder of the Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion and served as co-editor from 1983 to 1994. Ultimately, she served two terms as associate director of the American Academy of Religion (1992-94 and 1998-99), as well as a term as vice president (1995-96), as president-elect and as president (1996-97 and l997-98) of that august institution.

From 1976 to 1979, Plaskow was an assistant professor of religion at Wichita State University in Kansas. Beginning in 1979, she taught at Manhattan College in New York, rising from assistant to associate (1984-90) to full professor (1990-2013). She retired in 2013.

Relationships and Friendships

In 1969, Plaskow married rabbinics scholar Robert Goldenberg; their son, Alexander Goldenberg, was born in 1977. Plaskow and Godenberg separated in 1984. Plaskow came out as a lesbian in the 1980s. In 1986 she and Martha Ackelsberg, a government professor at Smith College, celebrated their commitment ceremony; following a health scare, they were legally married in Massachusetts in 2013.

Intellectual friendships formed through feminist gatherings and institutions have been especially influential in Plaskow’s life and thought. She met Carol Christ, with whom she edited the groundbreaking anthology Womanspirit Rising (1979) and several subsequent works, through the Yale Women’s Alliance. At the 1972 Conference on Women Exploring Theology at the ecumenical center at Grailville, Plaskow met Elisabeth Schussler-Fiorenza, with whom she edited the Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion and whose book on women in early Christianity, In Memory of Her (1983), had a profound effect on Plaskow’s expansive concept of Jewish women’s history. The women of B’not Esh, among them Martha Ackelsberg, Marcia Falk, Drorah Setel, and Sue Levi Elwell, stimulated Plaskow’s determination to create Jewish theology that was both authentically rooted and transformative.

Plaskow’s Feminist Theology

Plaskow’s theology has had a profound effect on Jewish women’s theological conversations in every decade since the 1970s. Both in the Jewish and the non-Jewish worlds, she is the best-known Jewish feminist theologian. The dialectic that distinctively marks Plaskow’s thought counterpoises the tensions and complementarities between Jewish thought and feminist religious thought in general. This dialectic is visible in Plaskow’s earliest work, “The Coming of Lilith” (1972), which originated in a group exercise at the conference on Women Exploring Theology at Grailville. “The Coming of Lilith” rewrites an ancient midrash by portraying the two wives of Adam, the outcast rebel Lilith and the more tractable Eve, encountering each other and forming a creative sisterly bond that exposes the unexamined bond between God and Man. In the culmination of their encounter, they resolve to transform the Garden. In retrospect, Plaskow sees the impact of non-Jewish thought on “The Coming of Lilith,” and the dearth of Jewish theological language and understandings (1999), but she also sees in it “my first incorporation of Jewish modes of thinking into my attempts to theologize” (2005). The importance of “The Coming of Lilith” can be gauged by the number of times it has been reprinted in both interfaith and Jewish feminist collections.

While “The Coming of Lilith” uses A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrashic narrative to expose the patriarchal template Judaism uses to shape its reality, Plaskow’s electrifying article, “The Right Question Is Theological” (1982), exposes The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhahas a patriarchal construction. Written in response to “Notes Toward Finding the Right Question,” by Cynthia Ozick (1979), Plaskow insists that theology rather than halakhah is primary. Halakhah results from theological presumptions about the fundamental otherness of women. Rather than waste time trying to mend an unmendable halakhah, Plaskow argues, women should remake theological discourse.

In Plaskow’s masterwork, Standing Again at Sinai (1990), all of the tensions, between being a woman, a feminist, a historically grounded person, a post-colonialist, on the one hand, and being a Jew, on the other, are merged into a feminist synthesis in which a dynamic, non-essentialist theology emerges from a unified feminist Jewish self. In Standing Again at Sinai, Plaskow breaks open and moves past all the previously intractable areas of struggle: patriarchal hegemony over the construction of Jewish history and sacred text, patriarchal privilege defining the community of Israel and distributing power in it, patriarchal monopolies justifying exclusively masculine God-language, and patriarchal understandings of body and sexuality.

Using the Rosenzweigian theological formulation God, Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, and Israel, Plaskow employs these terms in her own distinctive way. In her chapter on Torah, Plaskow argues for the use of feminist historical methodologies to uncover Jewish women’s history and cultures, yet she asserts that these will be inadequate without the use of feminist midrash and liturgy to reshape Jewish memory both in the past and in the present. She emphasizes the pluralism of the Jewish past as well as the pluralism of women’s experiences. Regarding halakhah, she is less negative than in “The Right Question Is Theological.” Rejecting both the anti-Judaic bias against law as a religious structure and the essentialist view that law is a distinctively masculine form, she regards law as a necessary element of all human cultures. “Perhaps what distinguishes feminist Judaism from traditional rabbinic Judaism,” she concludes, “is not so much the absence of rules from the former as a conception of rule-making as a shared communal process” (Sinai 71).

Plaskow’s chapter on Israel explores creating a community in which Jewish women would be present, equal, and responsible. The concern with responsibility leads Plaskow to trace oppression in both Diaspora communities and the state of Israel: sexual and economic hierarchies, Ashkenazis versus Jews of Sefardic or Middle Eastern origins, Israelis and diasporic Zionists versus the Palestinian Other.

Plaskow’s chapter on God challenges the hegemony of masculine metaphors for God. As in “The Right Question Is Theological,” she relies on the anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s account of how religious language and symbols function to legitimate social systems. If God is portrayed as father, human fathers will be viewed as God-like. If God is viewed as a dominating male, human institutions are likely to be male dominated. Hence, for Plaskow, the exploration of God language is inextricably tied to justice and authority in the human realm. Plaskow also critiques feminist God language. She argues for pluralistic imagery within monotheism, contesting pagan feminists’ charges that monotheism is essentially masculine and monopolistic. But she observes that the aspect of God that feminists have been least successful in translating into imagery is “the presence of God in empowered, egalitarian community” (Sinai, 155).

In the chapter following, Plaskow introduces an unorthodox topic: theology of sexuality. This addition to more traditional theological rubrics is necessary because, for Plaskow, sexuality is not a physical detail but an inherent part of our identity and experience. Drawing from traditional sources, she argues that Jewish tradition is ambivalent toward sexual expression and sexuality as an attribute. If feminist theology were able to overcome the dualisms inscribed in patriarchal sexuality, Plaskow argues, and if women were able to claim their own sexuality, we would come to understand our world as body-mediated, and our humanity as sensuous as well as rational. We would then perceive the erotic and the spiritual as interpenetrating categories. Awareness of how sexuality connects us to all things would help us to sanctify it and not misuse it. In the resulting new ethics, all sexual relationships would not base obligations on ownership or hierarchy, but on mutuality and joint empowerment.

This theme of embodiment and sexuality as the human characteristics most laden with implications for theology and ethics becomes a consistent thread throughout Plaskow’s lifework, notably in Goddess and God in the World: Conversations in Embodied Theology (2016), which she co-authored with the Christian feminist theologian Carol Christ, and in the articles comprising Judith Plaskow: Feminism, Theology, and Justice (2014). For Plaskow, problems of theodicy and evil, political justice both in the state of Israel and in the United States, and the possibilities for redemption and the repair of the world are inextricable from our understandings of human embodiment and sexuality. God is best understood as the ground of all the possibilities embodied humans can bring into being, both for good and for evil. She states her theology most clearly herself:

In technical theological language, I am a panentheist: I believe in

a God who is present in everything and yet at the same time is not

identical with all that is. . .To me, believing in God means believing

that, despite the fractured, scattered, and conflicted nature of our

experience of both the world and ourselves, there is a unity that

embraces and contains our diversity and that connects all things to

one another. (God and Goddess in the World 184-185).

As of 2020, Judith Plaskow is in her fifth decade of producing courageous, innovative, and broadly conceived feminist theology.

Selected Works by Judith Plaskow

“The Coming of Lilith: Toward a Feminist Theology.” In Women Exploring Theology at Grailville. Church Women United, 1972. Reprinted in Rosemary Ruether, ed., Religion and Sexism: Images of Women in the Jewish and Christian Traditions. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1974.

with Carol J. Christ, eds. Womanspirit Rising. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1979.

“The Right Question is Theological.” In On Being a Jewish Feminist, edited by Susannah Heschel. New York: Schocken Books, 1983. Preprinted as “God and Feminism,” Menorah Journal: Sparks of Jewish Renewal, Feb. 1982.

Standing Again At Sinai. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1992.

“Lilith Revisited.” In Eve & Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Readers on Genesis and Gender, edited by Kristin E. Dvam, Linda S. Shearing, and Valerie Ziegler. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1999.

The Coming of Lilith: Feminism, Judaism, and Sexuality 1983-2003. Boston: Beacon Press, 2005.

“Gender Theory and Gendered Realities—An Exchange Between Tamar Ross and Judith Plaskow.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies and Gender Issues 13 (Spring 2007): 207-251.

“Contemporary Reflection” on Vayeira, Yitro, Acharei Mot, and Ki Teitzei. The Torah: A Women’s Commentary, ed. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, 107-8, 423-24, 696-97, 1187-88. New York: URJ Press, 2008.

“Calling All Theologians.” In New Jewish Feminism: Probing the Past, Forging the Future, ed. Rabbi Elyse Goldstein, 3-11. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights, 2009.

“Dismantling the Gender Binary Within Judaism: The Challenge of Transgender to Compulsory Heterosexuality.” Heterosexism in Contemporary World Religion: Problem and Prospect, ed. Marvin Ellison and Judith Plaskow, 13-36. Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press, 2007. Reprinted in Balancing on the Mechitza: Transgender in the Jewish Community, ed. Noach Dzmura, 187-210. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2010.

“Remapping the Road from Sinai.” Co-authored with Elliot Rose Kukla. Sh’ma 38/646 (December 2007): 2-5. Reprinted in Balancing on the Mechitza: Transgender in the Jewish Community, ed. Noach Dzmura, 134-140. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2010.

“Beyond Sarah and Hagar: Muslim and Jewish Reflections on Feminist Theology.” Co-authored with Aysha Hidayatullah. In Muslims and Jews in America: Commonalities, Contentions, and Complexities, ed. Reza Aslan and Aaron J. Hahn Tapper, 159-172. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

“Wrestling with God and Evil.” In Chapters of the Heart: Jewish Women Sharing the Torah of Our Lives, ed. Sue Levi Elwell and Nancy Fuchs Kreimer, 85-93. Wipf & Stock, 2013.

“Feminist Jewish Ethical Theories.” In The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Ethics and Morality, ed. Elliot Dorff and Jonathan Crane, 272-286. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

With Carol P. Christ. Goddess and God in the World: Conversations in Embodied Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016.

Ozick, Cynthia. “Notes Toward Finding the Right Question.” Lilith Magazine no. 6 1979. Reprinted in On Being a Jewish Feminist, edited by Susannah Heschel New York: Schocken Books, 1983.

Schussler-Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In Memory of Her: Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Herder & Herder, 1994.

Ruether, Rosemary, ed. Womanguides: Readings Toward a Feminist Theology. Boston: Beacon, 1985.

Umansky, Ellen and Dianne Ashton, eds. Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality. Boston: Beacon, 1992.