Scandalous Dance Scenes, Romance Plots, and Jewish Literary Modernity

The hit show Bridgerton, which is about to launch its much-anticipated third season, has everyone talking about representation in romance fiction. Set in Regency England, this adaptation of Julia Quinn's beloved eight-book series about the marriage choices of eight aristocratic siblings has gotten attention for its steamy scenes and alternate universe with racially diverse British nobility (although without any Jewish characters, despite the fact that Quinn is herself Jewish). People who are new to the genre might be surprised to learn that there is an ongoing conversation about the extent to which historical romance novels include characters who don’t fit the mold of straight, white, able-bodied lords and ladies.

It’s a topic that offers writers an irresistible challenge: How do you write a compelling, convincing story about socially marginalized characters in which the fantasy isn’t completely overwhelmed by real historical trauma?

Romance novelists have challenged the frequent focus on the British aristocracy by working from alternative premises, including Beverly Jenkins's’ depictions of New Orleans’ Black elite, Alyssa Cole’s daring Loyal League spies of the Civil War, Vanessa Riley’s well-to-do mixed-race characters from the West Indies, Adriana Herrera’s Caribbean heiresses, and Courtney Milan’s delightful Wedgeford, a fictional, mostly Asian nineteenth-century English town. Romance novels tend to reflect the desires, fears, and values of the era in which they’re written, and these novels fuse our real-world concerns about racial justice with timeless entertainment: engaging characters, passion, and a happy ending.

Most of the romance authors listed above write for American audiences, and their discussions of race are deeply connected to the way this issue is addressed in the US today. Novels that examine the diversity of nineteenth-century England or the way the British aristocracy benefited financially from the slave trade do important work in uncovering a complex historical reality and helping readers process their no less fraught present.

But if we assume that light, formulaic fiction reflects both its historical setting and the time in which it was written, how might the discussion of race in historical romance novels shift when portraying Jews, a minority group that, in the twenty-first century US, is seen by many as white?

For many nineteenth-century Europeans, this wasn’t the case; Jews were seen as belonging to their own, non-white racial category, and their status was hotly contested. Jews confronted a variety of questions as they negotiated the possibility of social acceptance: Should they give up their religious customs and use of Yiddish to gain civil rights? What occupations should (or could) they pursue? Would Jewish women be invited to dance at balls? Were they appropriate marriage partners for Christian men?

These questions had serious consequences for European Jews, and although historical romance novels with Jewish themes remain rare, authors such as Felicia Grossman and Rose Lerner write about nineteenth-century Jewish topics in their romance fiction. Case in point: in a piece in Kveller in 2021, Alina Adams describes her 1995 novel The Fictitious Marquis as the “first Jewish Regency romance” and reflects on how expectations of representation have changed over the past 25 years.

Adams’s debut novel may be the first instance of a contemporary historical romance novel to feature a Jewish protagonist, but The Fictitious Marquis was not the first Jewish historical romance. Already in the nineteenth century, Jewish (and sometimes non-Jewish) writers delighted readers with romantic stories about Jews.

It was a time when Jews were shifting how they felt about arranged marriages, and the romantic choices of Jewish women were a topic of deep fascination. As scholars such as Naomi Seidman and Jonathan Hess have shown, romances set in biblical times, Spain around the time of the Inquisition, or even in the nineteenth century could become bestsellers. And bourgeois German writers often created a sense of intriguing distance by setting their works in traditionally-observant Yiddish-speaking small towns they referred to (somewhat problematically) as “ghettos.”

The Jewish romances in these works might not satisfy contemporary readers’ appetites for emotional development, female pleasure, or fluid prose. They often don’t even have a happy ending––especially when Jews and Christians fall in love. But just like contemporary novels, they give us a glimpse at what was on the minds of readers.

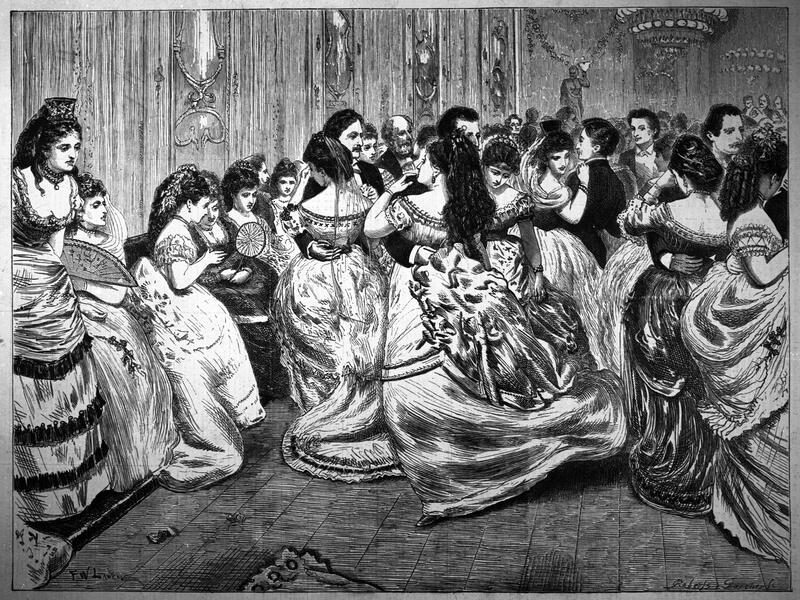

In the roughly 150-year period between 1780 and 1939, European Jews faced a dizzying array of social changes: religious reform and the development of neo-Orthodoxy, shifting ideas about women’s place in society, immigration to the US, war, migration from towns to European cities, and debates about whether they should have civil rights. Yet these dramatic changes didn’t always make for the most titillating fiction, at least not on their own. Fortunately, writers had another idea about how to convey these concerns while entertaining their readers: scandalous dancing.

Contemporary popular culture often portrays Jewish mixed-sex dancing as either absolutely forbidden in religious communities or as the punchline of a dirty joke. Yet long before Fiddler on the Roof, Jewish writers used partner dance as a powerful metaphor for social changes that transformed Jewish communities between the Enlightenment and the Holocaust.

Scandalous partner dances, like the waltz in the early nineteenth century, challenged notions of proper intimacy for couples on the dance floor. For many Jews, especially those who no longer felt as strictly bound by traditional religious law, mixed-sex dancing was an enjoyable marker of acculturation and a preferred way to meet potential romantic partners without the involvement of parents or a matchmaker. At a time when most European Jews faced legal barriers to full integration, an invitation to a non-Jewish ball offered the seductive possibility of social acceptance––at least for one night.

The appeal of dance was nearly universal, in life and in the literary imagination. Dancing took place in a variety of venues, from working-class taverns to elite balls. Patriots danced to celebrate their monarch’s birthday, while radicals attended Yom Kippur balls. Salon hostess Fanny von Arnstein and anarchist Emma Goldman both attended balls. Austrian Jewish writer Arthur Schnitzler saw dancing as part of being a member of the Viennese bourgeoisie, while Yiddish writer and journalist Abraham Cahan saw it as part of his participation in radical politics in Vilna. Social dancing was everywhere, and collectively writers described encounters on the dance floor in all the genres in which they wrote: novels, novellas, memoirs, short stories, plays, poetry, and more.

Between the Enlightenment and the Holocaust, the mixed-sex dance floor became a prominent Jewish space in a context of shifting gender expectations. Where men and women once studied, worked, prayed, and socialized in separate groups, young people increasingly mingled with members of the opposite sex in salons, cafés, political organizations, universities, and dance halls.

Memoirs from this period note the traditional expectation that men and women live separate lives and give dancing as an example of an officially forbidden activity. Writing in the early 1940s, Zionist feminist Puah Rakovsky, who was born in Bialystock in 1865, recalls, “Fifty or sixty years ago, Jewish girls from pious houses didn’t know anything about flirting, didn’t sit in coffee houses with suitors, didn’t go to dance classes. . . . A girl was only allowed to talk with boys who were close relatives, and even then they could converse only in the presence of her parents.” Mixed-sex dancing became a metaphor for changing gender norms in Jewish communities during the modern era. In literature, the dance floor was the most thrilling setting for young people to explore their newfound freedoms with the opposite sex.

In my book, It Could Lead to Dancing: Mixed-Sex Dancing and Jewish Modernity, I discuss how mixed-sex dance scenes—and fascination with the taboo itself—repeat throughout Jewish literature in a variety of languages during this pivotal period. Even more recently, novels like Kerry Greenwood’s 2007 Raisins and Almonds: A Phryne Fisher Mystery include intimate dancing. Greenwood opens with a scene at a foxtrot competition in a Jewish social club in 1920s Melbourne, Australia. Not surprisingly, more contemporary works also represent a definite step up in terms of female empowerment.

After I read Adams’s piece in Kveller, I quickly ordered The Fictitious Marquis and was rewarded with a scene in which the conman hero dances a scandalous waltz with the Jewish but passing-as-gentile heroine. While the book doesn’t acknowledge Jewish prohibitions on men and women dancing, it provides a delicious example of how the waltz offended notions of early nineteenth-century bourgeois morality.

The first Jewish Regency novel may be a revolutionary step in terms of Jewish inclusion in the romance genre, and yet at the same time, it can’t escape the allure, intrigue, and enjoyable predictability of a good mixed-sex dance scene. Bridgerton also celebrates the power (and spectacle) of the ballroom, and the third season would be a great opportunity for the writers to show how Jewish characters fit into the racially-inclusive universe of the series, both on and off the dance floor.