Abigail: Bible

Abigail, the intelligent and beautiful wife of the wealthy but boorish Nabal, eventually marries David, the future king of Israel, after Nabal’s death. While running a “protection racket” in the area of Carmel, David asks for provisions for himself and his men but Nabal refuses, so the young warrior prepares for slaughter. Abigail quickly intervenes, sending a feast ahead and greeting David on the way. In an eloquent speech, she persuades him to shed no blood and prophesies that he will be king. Upon hearing what she has done, Nabal dies. David then sends for Abigail to become his wife as she intimated. She bears David a son, who never becomes a contender for the throne, and though a prophet and wise woman, she plays no further role in court history

Abigail, the wife of Nabal of Carmel, is the only woman in the Hebrew Bible who is described as both intelligent and beautiful. After enumerating Nabal’s enormous wealth in flocks (1 Sam 25:2), the narrative introduces her in contrast to him. She is “of good sense and beautiful in looks,” while he is “hard and evil in his deeds” (v. 3). As Abigail later asserts (v. 25), his character befits his name, Nabal, meaning “fool” or “boor” (see Prov 17:7, 21, and Isa 32:6). He is also identified as a Calebite, perhaps a rival clan for the Judean monarchy. (David has not yet been publicly anointed king). Alternatively, according to the written text (ketiv), he is just “like his heart [ke-libo].” Later, the narrative recounts that “his heart [lev] died within him and he became like stone” (v. 38). Mean and inhospitable, he meets his fate, measure-for-measure, in the petrification of his hard heart. This characterization explains why Nabal responds so rudely to David’s request for sustenance, likening him to a runaway servant (vv. 10–11), and why one of his own young men turns to Abigail to save them all, explaining: “he is such a nasty fellow that no one can speak to him” (v. 17). Further, it accounts for Abigail’s motivation: why she intervenes secretly to provide a feast for David and his men without consulting her husband. In a subtle twist, she simultaneously saves her household and allies herself with David, eventually in matrimony when she is fortuitously widowed.

Abigail’s Intervention Prevents a Bloodbath

The chapter is set during the sheep-shearing festival, a time renowned for feasting and revelry. David requests food for himself and his band of six hundred men who, while in flight from the mad King Saul, have been operating a kind of “protection racket” against marauders for the shepherds and flocks in the area (vv. 5–8, corroborated by the report of Nabal’s own servant in vv. 15–16). When Nabal refuses, insulting David and his band as riffraff (vv. 10–11), the young warrior and four hundred of his men gird themselves for bloodshed. Enraged, David swears on oath: “May God do thus and more to David, if by morning, I leave a single pisser against the wall!” (v. 22). In this crude expression, we are privy to the first glimpse of evil in David’s character.

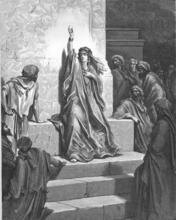

Overhearing the dialogue, one of the servants runs to Abigail, begging her to intervene. She quickly assembles an elaborate feast, which is loaded up on donkeys and sent in advance. She then intercepts David to persuade him against fulfilling his violent oath (which the reader only hears retroactively, after she is seen approaching, v. 20). Before we are struck by the full force of the oath, we anticipate its undoing.

Abigail’s Eloquent Speech

Abigail alights from her donkey and prostrates herself before David. In her long, eloquent speech (vv. 24–31)—repeatedly addressing David as “lord” and herself as “maidservant”—she appeals to him to shed no blood. She promises that, if he restrains himself from bloodguilt, then God will dispatch David’s enemies (v. 29), alluding to the death of Nabal, and perhaps to Saul’s as well. She further portends that God will establish a “sure house” for David (v. 28), foreshadowing Nathan’s prophecy of an everlasting dynasty for the king (2 Samuel 7). She ends her speech with a hint: “when the LORD has dealt well with my lord, then remember your handmaid” (2 Sam 25:31). David then praises her good sense and expresses gratitude that she restrained him from bloodshed, uttering an oath to counter the prior violent one (v. 34). As in the encounters with King Saul that frame this story (chs. 24 and 26), David’s restraint from slaying his rival demonstrates his worthiness of kingship. Yet it also anticipates his darker side, when David does not restrain himself from adultery and murder in the story of Bathsheba and Uriah (2 Samuel 11–12). His folly there does become the “cause of grief and pangs of conscience for having shed blood without cause” (v. 31).

Based on her prescience, the Talmud identifies Abigail as one of the seven female prophets in the Hebrew Bible (b. Megillah 15a). More likely, she is keenly perceptive about the shifting tides of history.

Nabal’s Death and Abigail’s Marriage to David

When Abigail returns home, she finds her husband drunk from feasting “like a king” and waits until the morning to tell him what she has done (v. 36). His heart then strangely turns to stone and he dies ten days later, struck by “the Lord” (God) (v. 38). David, hearing that she has been widowed, sends for her. She obsequiously prostrates herself, calling David “lord” and herself “maidservant prepared to wash [his] servants’ feet”; though, ironically, she follows the messenger with five maids on donkeys in tow (vv. 41-42). She then becomes his wife. Because of the hint to David (v. 34), the mysterious cause of Nabal’s death, and no record of mourning her boorish husband, some scholars and modern creative renditions have read Abigail as conniving. Yet, there is no hint of illicit behavior on her part. Rather, the story stands in stark contrast to the Bathsheba episode, when the king takes a woman married to another man (Uriah) while he is serving the king, fighting “the Lord’s battles.” And David has him killed on the front in order to cover for the adultery. In the Abigail story, on the other hand, the woman is married to an evil husband and prevents him from murdering Nabal (and all the males of the household), as David acknowledges (vv. 33–34). As Adele Berlin points out: “The Abigail story contains no illicit sex, though the opportunity was present; the Bathsheba story revolves around an illicit relationship. In the Abigail story, David, the potential king, is seen as increasingly strong and virtuous, whereas in the Bathsheba story, the reigning monarch shows his flaws ever more overtly and begins to lose control of his family.”

Epilogue

Abigail becomes David’s third wife, after Ahinoam of Jezreel (1 Sam 25:43) and Michal, daughter of Saul (1 Sam 18:27). Unlike Michal, whom David leaves behind when fleeing from King Saul (19:11–17), Abigail and Ahinoam accompany him to Gath (1 Sam 27:3). When David is away, the Amalekites attack Ziklag and carry off the wives, David’s people, and his possessions, but David is able to rescue them (1 Sam 30:1–5, 18).

Abigail is present with David in Hebron when he is publically inaugurated king, and she bears him a son called Chileab, meaning “according to the father” (2 Sam 3:3; Daniel in 1 Chr 3:1)—perhaps to assert David’s paternity as unambiguous. The meaning of her own name then takes on new resonance, meaning “my father’s joy” or “my father rejoices,” from the Hebrew root g-y-l “to rejoice.” Yet the son, Chileab, never becomes a contender for the throne and, beyond this episode, Abigail plays no role in the court history.

Adelman, Rachel. The Female Ruse: Women’s Deception and Divine Sanction in the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2015.

Bach, Alice. The Pleasure of Her Text. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1990.

Berlin, Adele. “Abigail.” In Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books and the New Testament, edited by Carol Meyers, Toni Craven, and Ross S. Kraemer, 43–44. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Bodi, Daniel, ed. Abigail, Wife of David, and Other Ancient Oriental Women. Hebrew Bible Monographs 60. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013.

Garsiel, Moshe. “Wit, Words and a Woman: I Samuel 25.” In On Humour and the Comic in the Hebrew Bible, edited by Yehuda Radday and Athalya Brenner, 163–68. Sheffield: Almond, 1990.

Levenson, Jon D. “1 Samuel 25 as Literature and History.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 40 (1978): 11–28.

Polzin, Robert. “Providential Delays (2 Sam. 24:7-26:25).” In Samuel and the Deuteronomist: A Literary Study of the Deuteronomic History, Part 2, 1 Samuel, 205–15. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Shalev, Meir. “Protection in Carmel.” In Tanakh ‘Akhshav [The Bible Today], 19–23. [In Hebrew.] Tel Aviv: Schocken, 1985.

Shields, Mary. “A Feast Fit for a King: Food and Drink in the Abigail Story.” In The Fate of King David: The Past and Present of a Biblical Icon, edited by Tod Linafelt, Timothy Beal, and Claudia V. Camp, 38–54. New York and London: T&T Clark, 2010.