Bella Abzug

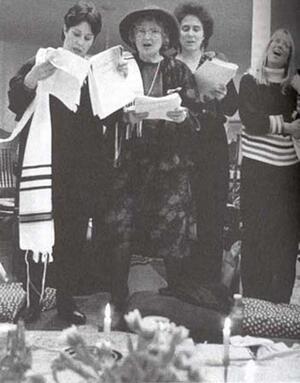

Feminist seders have provided an important context for developing women’s spirituality. In 1975, a group of Israeli and American women decided to create their own Passover seder based on their experiences as Jewish women. Now an annual event held in Manhattan, it has been attended by Esther Broner, Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Bella Abzug, Grace Paley and several other "Seder Sisters" who have played important roles in the development of Jewish feminism. Shown here are Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler and Letty Cottin Pogrebin at the Women's Seder in 1991.

Photo: Joan Roth

A formidable leader of the women’s movement, Bella Abzug fought to pass the Equal Rights Amendment and other vital legislation for the rights of women. Early in her career, Abzug earned distinction as one of the few attorneys willing to stand up to the House Un-American Activities Committee. During her three terms in Congress, she advocated for groundbreaking bills, including the Equal Rights Amendment and crucial support of Title IX. In 1977, she presided over the historic first National Women’s Conference in Houston. Towards the end of her career, she focused on global issues of women’s rights and human rights, ensuring that those issues were continually addressed by the United Nations.

Introduction

Born in the Bronx on July 24, 1920, Bella (Savitzky) Abzug predated women’s right to vote by one month. A tireless and indomitable fighter for justice and peace, equal rights, human dignity, environmental integrity, and sustainable development, Bella Abzug advanced human goals and political alliances worldwide.

As co-creator and president of the Women’s Environmental and Development Organization (WEDO), a global organization, Abzug galvanized and helped transform the United Nations agenda regarding women and their concerns for human rights, economic justice, population, development, and the environment. WEDO represented the culmination of her lifelong career as public activist and stateswoman.

Family and Education

Known by her colleagues as a “passionate perfectionist,” Abzug believed that her idealism and activism grew out of childhood influences and experiences. From her earliest years, she understood the nature of power and the fact that politics is not an isolated, individualist adventure. A natural leader, although a girl among competitive boys, she delighted in her prowess at marbles, or “immies.” When the boys tried to beat her or steal her marbles, Abzug defended herself fiercely with unmatched skill. She also played checkers, traded baseball cards, climbed trees, became a graffiti artist, and understood the nuances, corners, and risks of city streets, which were her playground.

In synagogue with her maternal grandfather, Wolf Taklefsky, who was her babysitter and first mentor, Bella used her beautiful voice and keen memory to delight the elders with the brilliance of her prayers, and with her ability to read Hebrew and daven [pray]. Although routinely dispatched to the women’s place behind the Synagogue partition between men and womenmehizah, by the time she was eight she was an outstanding student in the Lit. "study of Torah," but also the name for organizations that established religious schools, and later the specific school systems themselves, including the network of afternoon Hebrew schools in early 20th c. U.S.Talmud Torah school she attended, and a community star.

Her Hebrew school teacher, Levi Soshuk, recruited her to a left-wing labor Zionist group, Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir [the young guard]. By the time she was eleven, Abzug and her gang of socialist Zionists planned to go to Israel together as a A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kevuzah. In the meantime, they were inseparable and traveled throughout New York City, hiked in the countryside, danced, and sang all night, and went to free concerts, museums, the theater, picnics, and meetings. Above all, they raised money for a Jewish homeland—with Abzug in the lead. At subway stops, she gave impassioned speeches, and people tended to give generously to the earnest, well-spoken girl. From her first gang, Abzug learned about the power of alliances, unity, and alternative movements.

Hitler came to power the year her father, Emanuel, died, and Abzug emerged as an outspoken thirteen-year-old willing to break the rules. Although prohibited by tradition from saying Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.kaddish for her father in synagogue, Abzug did so anyway. Every morning before school for a year, she attended synagogue and davened. The congregants looked askance and never did approve, but nobody ever stopped her. She simply did what she needed to do for her father, who had no son—and thus learned a lesson for life. Be bold, be brazen, be true to your heart, she advised others: “People may not like it, but no one will stop you.”

Abzug never doubted that her father would have approved. Manny Savitzky adored his daughters. The butcher whose shop bore his personal mark of protest during and after World War I— “The Live and Let Live Meat Market” in the Clinton-Chelsea section of Manhattan—had a profound impact on his daughter’s vision. Protest was acceptable; activism took many forms. After all, he had learned to tolerate Abzug’s pack of socialist Zionist friends who kept her out all night from the age of eleven. There was always music in her parents’ home. Her father sang with gusto, her sister, Helene (five years older), played the piano—the grand piano that filled the parlor—and Bella played the violin. Every week, the entire family, including grandparents, congregated around music, led in song by her father.

Abzug’s mother also supported her rebellion—all her rebellions. Esther Savitzky appreciated her younger daughter’s talents and encouraged her every interest. By the age of thirteen, a leader in the crusade for women’s rights, equal space, dignity, and empowerment for girls was in active training. According to her mother, “Battling Bella” was born bellowing. A spirited tomboy with music in her heart and politics in her soul, Abzug was both vastly popular and determinedly studious.

She continued violin lessons through high school. From Talmud Torah she went to Florence Marshall Hebrew High School after classes at Walton, and to the Teachers Institute at the Jewish Theological Seminary after classes at Hunter College. She earned additional money for her family by teaching Hebrew, and also committed herself to political activities. Elected class president at Walton High School in 1937 and student government president of Hunter College in 1941, Abzug made a profound impression on teachers, contemporaries, and history.

As student council president at Hunter College, she opposed the Rapp-Coudert committee, which sought to crush public education and was on a witch-hunt against “subversive” faculty. A political science major, Abzug was active in the American Student Union and was an early and ardent champion of civil rights and civil liberties. At Hunter, she was at the center of a permanent circle of friends who remained political activists and lifelong champions of causes for women, peace, and justice. Journalist Mim Kelber, who first met Abzug at Walton, was editor of Hunter’s student newspaper the Bulletin, remained a political partner, co-founded WEDO, and now edits its impressive newsletter and publication series.

With her brilliant college record and leadership awards, Abzug won a scholarship to Columbia University Law School. (Harvard, her first choice, turned her down; its law school did not accept women until 1952.) Her record at Columbia was splendid. She became an editor of the Law Review, and her reputation as tough, combative, diligent, and dedicated grew. In addition, two new enthusiasms entered Bella’s life during law school: poker and Martin Abzug.

Marriage

She met Martin Abzug while visiting relatives in Miami after her graduation from Hunter. At a Yehudi Menuhin concert for Russian war relief, she saw a young man staring and smiling at her. They met; they dated; he left for military service; they corresponded. Upon his return, he wanted to party. She wanted to study. He would meet her at midnight at the law library. A writer, Martin Abzug knew how to type; she never did. He typed her briefs and promised that even when they married and had children she would continue to work—her major concern at the idea of marriage.

They married on June 4, 1944. The son and partner of an affluent shirt manufacturer (A Betta Blouse Company), who published two novels and later became a stockbroker, Martin Abzug encouraged all of his wife’s interests and ambitions—including those that were demonstrably dangerous during the McCarthyite years of the Cold War. He admired her integrity, vision, and combative style, and until his death remained her steadfast supporter. For forty-two years, their marriage, based on love, respect, and a generosity of spirit unrivaled in political circles, enabled Abzug’s activities. His death in 1986 affected her deeply and she published a moving article about him, entitled “Martin, What Should I Do Now?”

Immediately after law school, Abzug joined a labor law firm that represented union locals. Routinely overlooked when she entered an office to represent the United Auto Workers, or the Mine, Mill and Smelting Workers, or local restaurant workers, she decided to wear hats. Hats made all the difference when it came to recognition and even respect, and they became her trademark.

For fifteen years, Abzug, her husband, and their two daughters—Eve Gail, called Eegee, born in 1949, now a sculptor and social worker; and Isobel Jo, called Liz, born in 1952, now an attorney and political consultant—lived in Mount Vernon, an integrated suburb that the parents believed the girls would benefit from. When the family moved to Greenwich Village, a center of urban activity, everybody was happier.

Law Career

During the 1950s, Abzug was one of very few independent attorneys willing to take “Communist” cases. With her husband’s encouragement, she opened her own office, defending teachers, entertainment, radio, and Hollywood personalities assaulted during the witch-hunt.

She also defended Willie McGee. In an internationally celebrated case, McGee, a black Mississippian, was falsely accused of raping a white woman with whom he had had a long-term consensual relationship. Abzug appealed the case before the Supreme Court and achieved two stays of execution when she argued that “Negroes were systematically excluded from jury service.” But she did not achieve a change of venue, and after the third trial and conviction, all appeals were denied.

On her trip south to Jackson for the special hearing board appointed by Mississippi’s governor, Abzug never thought much about her personal safety, even though she was pregnant at the time. She realized she was in trouble, however, when the hotel room she had booked was denied her and no other room made available. When a taxi driver offered to take her fifteen miles out into the country to find a place to stay, she returned to Jackson’s bus station and spent an unsettling night.

At court the next morning, she argued fervently for six hours on behalf of racial justice, protesting the clear conspiracy to deny Willie McGee’s civil rights, as well as the long tradition of race prejudice and unfair discrimination. Canceling his death sentence, Abzug argued in 1950, would restore faith in U.S. democracy throughout the world. Despite worldwide publicity, protest marches, and Abzug’s passionate plea to prevent another legal lynching, McGee went to the electric chair. Abzug had a miscarriage, but her dedication to the cause of justice was strengthened by her days in Mississippi.

In 1961, Abzug and her Hunter circle (Mim Kelber, Amy Swerdlow, and Judy Lerner) joined others (including Dagmar Wilson, Claire Reid, and Lyla Hoffman) to create Women Strike for Peace. During the next decade, they lobbied for a nuclear test ban treaty, mobilized against Strontium-90 in milk and protested against the war in Indochina. In the 1960s, Abzug became a prominent national speaker against the war and against poverty, racism, and violence.

Congress

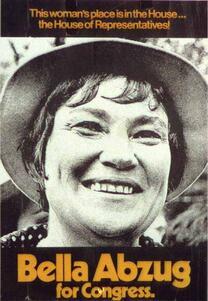

A leading reform Democrat, a successful attorney, a popular grass-roots activist, Abzug was urged to run for Congress, which she agreed to do at the age of fifty in 1970. Stunning and galvanizing, with her hats and her homilies, she became a household symbol for dramatic change. Representing Greenwich Village, Little Italy, the Lower East Side, the West Side, and Chelsea, she was the first woman elected to Congress on a women’s rights/peace platform and the second Jewish women elected to the House. New York agreed, “This woman’s place is in the House—the House of Representatives.”

In the House, she cast her first vote for the Equal Rights Amendment. As a member of the Committee on Public Works and Transportation, she brought more than six billion dollars to New York State in economic development, sewage treatment, and mass transit, including ramps for people with disabilities and buses for the elderly.

As chair of the Subcommittee on Government Information and Individual Rights, she coauthored three important pieces of legislation: the Freedom of Information Act, the Government in the Sunshine Act, and the Right to Privacy Act. Abzug’s bills exposed many secret government activities to public scrutiny for the first time. They allowed her and others to conduct inquiries into covert and illegal activities of the CIA, FBI, and other government agencies. The first member of Congress to call for Nixon’s impeachment, Abzug helped journalists, historians, and citizens to combat the disinformation, misinformation and generally abusive tactics that marked so much of the Cold War and blocked for so long the path toward human rights.

Above all, Abzug achieved splendid victories for women. She initiated the congressional caucus on women’s issues, helped organize the National Women’s Political Caucus, and served as chief strategist for the Democratic Women’s Committee, which achieved equal representation for women in all elective and appointive posts, including presidential conventions. She wrote the first law banning discrimination against women in obtaining credit, credit cards, loans, and mortgages, and introduced pioneering bills on comprehensive childcare, Social Security for homemakers, family planning, and abortion rights. In 1975, she introduced an amendment to the Civil Rights Act to include gay and lesbian rights.

Reelected for three terms, Abzug served from 1971 to 1977 and was acknowledged by a U.S. News & World Report survey of House members as the “third most influential” House member. In a 1977 Gallup poll, she was named one of the twenty most influential women of the world. The pipe-smoking Republican member of the House, Millicent Fenwick, once said that she had two heroes, two women she admired above all: Eleanor Roosevelt and Bella Abzug. They shared one thing, Fenwick said: They meant it! Women of vast integrity, they spoke from the heart, and they spoke truth to power. Although she agreed politically with Abzug on virtually nothing, Fenwick explained, Abzug was her ideal.

Post-Congressional Career

After Abzug was defeated in a four-way primary race for the Senate in 1976 by less than one percent, President Carter appointed her chair of the National Commission on the Observance of International Women’s Year and, later, co-chair of the National Advisory Commission for Women.

Active in the UN Decade of Women conferences in Mexico City (1975), Copenhagen (1980) and Nairobi (1985), Abzug became an esteemed leader of the international women’s movement. She also led the fight against the Zionism Is Racism resolution passed in 1991, which was repealed in 1985 in Nairobi. Long active in supporting Israel, especially in Congress and in Israeli-U.S.-Palestine peace efforts, she insisted that Zionism was a liberation movement.

In November 1991, WEDO convened the World Women’s Congress for a Healthy Planet. Fifteen hundred women from eighty-three nations met in Miami, Florida, to produce the Women’s Action Agenda for the twenty-first century. This agenda became the focus of UN conferences throughout the preparations for the UN Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing in 1995 and created an international women’s caucus that transformed the thinking and policies of the UN community. Abzug promoted the program around the world.

Later Life and Legacy

In the face of personal medical challenges, including breast cancer and heart disease, Abzug continued to confront global problems of poverty, discrimination, and the violent fallout of this “bloodiest century in human history.” As chair of New York City’s Commission on the Status of Women (1993–1995), and in partnership with Greenpeace and WEDO, she launched a national grass-roots campaign against cancer called “Women, Cancer and the Environment: Action for Prevention.”

She ate macrobiotically, swam regularly, and played poker fiercely, maintained a loving relationship with her daughters, with whom she shared a vacation home, and entertained her countless and loving friends (her “extended family”) with her great good humor and her love of song. Her friendships with people from Hollywood to New York are legion. Woody Allen directed her in Manhattan, she played alongside Shirley MacLaine in Madame Sousatzka, and her magical rendition of “Falling in Love Again” inspired feminist troubadour Sandy Rapp to compose a ballad, “When Bella Sings Marlene.” One line of the song reads, “On the second refrain of ‘moths to the flame,’ spirits fill the room.”

Shameless about enlisting her friends and colleagues to her causes, Abzug was also known for her boundless generosity. She remained an optimist, and her mission, her challenge and her legacy are clear:

It’s not about women joining the polluted stream. It’s about cleaning the stream, changing the stagnant pools into fresh, flowing waters.

Our struggle is [against] violence, intolerance, inequality, injustice.

Our struggle is about creating sustainable lives, and attainable dreams.

Our struggle is about creating violence-free families… violence-free streets, violence-free borders.

Our call is to stop nuclear pollution. Our call is to build real democracies not hypocrisies. Our call is to nurture and strengthen all families. Our call is to build communities, not only markets. Our call is to scale the great wall around women everywhere.

Bella Abzug’s understanding of the need for an international network of women working across this troubled planet for decency, justice, and peace fortified a global sisterhood never before imagined. With a song in her throat and a very high heart, she was a boundless source of hope for the future. Abzug, who died on March 31, 1998, lived every day to the fullest and blessed every day with the spiritual fervor of her responsibility and commitment to all people—one life, one weave.

Faber, Doris. Bella Abzug (1976).

The Bella Abzug Reader. Edited by Mim Kelber and Libby Bassett. New York: Mim Kelber, 2003.

Gates, Trevor G., and Margery C. Saunders. "Bella Abzug, queer rights, and disrupting the status quo." Journal of Social Change 7, no. 1 (2015): 6.

Kelber, Mim. "Carter and Women: The Friday Night Massacre." The Nation. 4 February l979.

Levine, Suzanne, and Mary Thom. Bella Abzug: How one tough broad from the Bronx fought Jim Crow and Joe McCarthy, pissed off Jimmy Carter, battled for the rights of women and workers, rallied against war and for the planet, and shook up politics along the way: An oral history. Macmillan, 2007.

Levy, Alan H. The Political Life of Bella Abzug, 1920–1976: Political Passions, Women's Rights, and Congressional Battles. Lexington Books, 2013.

Masaya, Sato. "Bella Abzug's Dilemma: The Cold War, Women's Politics, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict in the 1970s." Journal of Women's History 30, no. 2 (2018): 112-135.

Rodgers, Kathy. "Bella Abzug: A leader of vision and voice." Colum. L. Rev. 98 (1998): 1145.

Swerdlow, Amy. Women Strike for Peace: Traditional Motherhood and Radical Politics in the 1960s (1993).

Zarnow, Leandra. "Braving Jim Crow to Save Willie McGee: Bella Abzug, the Legal Left, and Civil Rights Innovation, 1948–1951." Law & Social Inquiry 33, no. 4 (2008): 1003-1041.

Zarnow, Leandra Ruth. Battling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug. Harvard University Press, 2019.