Peace Movement in the United States

Throughout the twentieth century, Jewish women played a major role in American peace organizations and movements. Protesting against issues like nuclear proliferation and the Vietnam War, these groups also expanded their interests to align with the civil rights and women’s liberation movements. Jewish women have also been in prominent roles advocating for peace between Israel and Palestine, both in the Knesset and with private organizations, especially after the 1982 war in Lebanon. In the many international women’s peace conferences in the late twentieth century, Jewish women were featured guests; these gatherings often brought together Palestinian and Israeli Jewish women to discuss their experiences.

The contemporary American Jewish women’s peace movement draws its roots from several earlier movements and organizations: the early work of the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW); women’s peace groups such as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) and Women Strike for Peace (WSP); the various movements for social justice in the United States, especially the civil rights and anti–Vietnam War movements; the feminist movement, and the development of a specifically Jewish feminism; Jewish groups in the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.diaspora formed to question Israeli policies regarding war, peace, and the Palestinians; and, especially, the Israeli women’s peace movement.

A Long History of Organizing for Peace

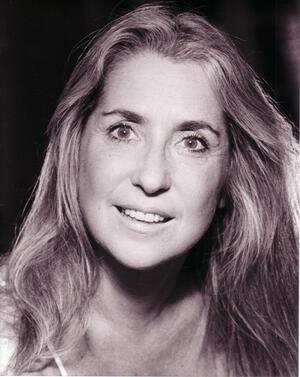

Educator and founder of the World Affairs Council and Center at the University of Minnesota, Fanny Fligelman Brin (1884–1961).

Image courtesy of the University of Minnesota Alumnae Association via The Washington Nuclear Museum and Education Center.

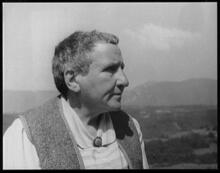

Bella Abzug at a New York press conference in 1972.

Copyright © Diana Mara Henry, dianamarahenry.com

As early as 1908, more than a decade before other national Jewish organizations addressed the problem, the National Council of Jewish Women created a Committee on Peace and Arbitration to study the causes of war. Under the leadership of Fanny Brin, the committee brought pacifist ideas before the membership through articles placed in NCJW publications, resolutions calling for the abolition of war, and speeches by well-known pacifists. Jeannette Rankin, the first woman member of Congress and a pacifist who voted against World War I, and suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt were among the keynote speakers at NCJW assemblies.

NCJW affiliated with the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, founded in 1915 to promote cooperation among women of all nations in pursuing peace based on social and economic justice. In 1925, NCJW participated with eleven other women’s organizations in a National Conference on the Cause and Cure of War. Representing millions of women, the coalition lobbied for United States endorsement of the World Court and the League of Nations and called for international legislation against war. With WILPF, NCJW called on the government to reduce military budgets, worked for passage of a law outlawing chemical and biological weapons, and demanded a prohibition against United States declarations of war without a national referendum.

In addition to the NCJW’s organizational involvement in peace efforts, individual Jewish women have long been active in peace organizations such as WILPF, WSP, and the movement to end American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Women Strike for Peace began on November 1, 1961, when thousands of mothers staged a national one-day protest to “End the Arms Race, Not the Human Race.” WSP protested the toxic effects of nuclear testing and was influential in the signing of the first international test ban treaty; initiated the measurement of radiation resulting from nuclear test emissions and focused public attention on the radiation contamination of milk; established a Clearing House on the Economics of Disarmament, which challenged the popular belief that military spending is good for the economy; and demonstrated the benefits of conversion to a peace-oriented economy.

When the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), attempting to discredit the peace movement, served subpoenas on fourteen members of WSP in 1962, the organization used media savvy, ridicule, humor, and theater so creatively that they struck a crucial blow at HUAC itself. WSP members filled the audience, brought babies into the hearing room, gave roses to the subpoenaed witnesses, and scolded the hearing officers in schoolmarm tones, simultaneously proclaiming their moral opposition to the arms race. Portions of the press, already becoming critical of HUAC, gave WSP substantial and favorable coverage.

By 1967, WSP was demonstrating against the Vietnam War, uniting its antiwar activities with the struggle for civil rights, and occasionally practicing civil disobedience. They formed a new women’s antiwar coalition named the Jeannette Rankin Brigade in honor of the eighty-seven-year-old pacifist’s militant nonviolent stance against war and conducted a “die-in,” a sit-in, and a Women’s March on the Pentagon.

Among the notable Jewish members of Women Strike for Peace were Amy Swerdlow, Bella Abzug (who won election to Congress with WSP support), Pearl Willen (former president of the NCJW), and Cora Weiss, a leading member of WILPF. They joined such prominent civil rights leaders as Rosa Parks, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Coretta Scott King in the endeavor.

WSP explicitly stressed women’s concerns, practices, and philosophical approaches to questions of war and peace. Having begun with conventional, middle-class housewives’ conceptions of the social role of women, basing their political efforts outside the home on their roles as mothers, WSP members gradually came to question those traditional definitions. By the 1970s, their daughters’ generation was forming the second wave of the feminist movement and challenging war as “masculinist” behavior, related to the subordination of women.

Simultaneously, Jewish women, many of whom were participants in the feminist second wave, began to challenge the subordination of women within the Jewish religion, American Jewish communities and organizations, and Israeli society. As a peace movement developed within Israel, Israeli women expressed dissatisfaction with their exclusion from important roles within it.

Jewish Peace Movements and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

An explicitly Jewish peace movement emerged out of a confluence of forces in the 1970s. The 1967 war and Israel’s annexation of the West Bank, Gaza, Sinai, and Golan changed the physical and political terrain of Israel. It altered the relationship between the United States and Israel, newly focusing the attention of United States Jews on Israel. It transformed the nature of Palestinian political movements and fostered peace movements within Israel and the diaspora.

Although Tandi, the “Movement of [Palestinian and Jewish] Democratic Women in Israel,” had formed as early as 1948 to work for peace and equal rights for women and children, it stood largely alone until a number of Israeli peace movements organized in the 1970s. In 1975, Marcia Freedman, an American-born member of the Israeli Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset, elected with the support of the Israeli women’s movement, advocated a “two-state solution” to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, that is, negotiations toward a Palestinian state alongside Israel. In 1978, Peace Now formed in Israel, and American Friends of Peace Now in the United States.

Within the United States, Jews began to form organizations such as Breira (1973–1978), proposing that the Israeli Labor Party pursue peace more affirmatively. In 1980, New Jewish Agenda formed as “a progressive voice within the Jewish community and a Jewish voice within the Left community.” A multi-issue group, it, too, soon focused on promoting the two-state solution.

The 1982 war in Lebanon created a turning point in the formation of Israeli-Palestinian peace movements. The massacres at Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps of hundreds of Palestinians, predominantly women and children, by Lebanese Falange forces under Israeli military supervision caused painful soul-searching and protest demonstrations by Jewish women and men in Israel and in the diaspora. Four hundred thousand Israelis, constituting 10 percent of the Israeli people, demonstrated against the war and the massacres. Thousands of Jews and non-Jews demonstrated throughout the diaspora.

The International Jewish Peace Union (IJPU), formed in Paris in 1982 in response to the Lebanon War, was quite male-oriented. Among the organizers of American chapters, however, were Ellen Siegel, who had practiced nursing (and seen conditions firsthand) in Lebanon, Hannah Davis (also a member of New Jewish Agenda), and Ellisa Sampson, an observant Jew with a long history of activism and political analysis dating back to her experiences living in Israel from 1972 to 1978. Sampson led the New York chapter.

The IJPU initially concentrated on the Israeli incursion into Lebanon and supported Yesh Gvul, a movement of Israeli soldiers who refused to serve in the occupied territories. Later, influenced by an increasingly female membership and by the activities of the Israeli, Palestinian, and Jewish American women’s peace movements, the IJPU also organized medical relief in Lebanon and the territories, most of whose recipients were women.

Feminism, Peace, and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict moved Jewish women to act for peace in their own name as Jews and as women. Initially, however, the response to this conflict brought about splintering within the feminist movement, within peace groups, and among Jews themselves. Many Jews who had been very active in fighting against the Vietnam War were disturbed when their fellow peace activists championed Palestinian rights, criticized Israeli policies, or attacked Zionism.

Confrontations regarding Zionism and Palestinian-Israeli relations roiled the United Nations Decade for Women conferences in Mexico (1975) and Copenhagen (1980), and numerous other feminist conferences, newspapers, and other institutions. Fierce disagreements agitated the Jewish caucus of the (U.S.) National Women’s Studies Association and several International Women’s Day celebrations. Eventually, however, although strong disagreement remained, many Jewish women (along with Arab women) took a leading role in promoting peace in the Middle East.

In 1985 Reena Bernards, executive director of New Jewish Agenda, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, an editor of Ms. Magazine, and Gail Pressberg, director of Middle East programs at the American Friends Service Committee, together with Alice Shalvi, organized a Dialogue Group to plan for more constructive relations between Jews and Arabs at the forthcoming “End-of-Decade” UN Conference on Women. They invited prominent Jewish women from mainstream United States Jewish organizations, women from the Arab American Anti-Discrimination Committee, and leaders of the Feminist Arab Network. They succeeded in creating a model for discussion of grievances allowing for genuine communication.

By then American Jewish feminists and lesbian feminists had published a number of influential anthologies, poems, and essays on various themes. Letty Cottin Pogrebin’s pivotal article “Anti-Semitism in the Women’s Movement” addressed controversies about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz published interviews with Israeli peace activists Chaya Shalom, Galia Golan, and Lil Moed. Evelyn Torton Beck published Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology, including some reflections by United States and Israeli Jews about Israel.

Six prominent poets and writers formed Di Vilde Chayes to express their support for Israel as a Jewish state, their chagrin at Israeli treatment of Palestinians (particularly within the occupied territories of the West Bank and Gaza), and their anger at antisemitism expressed among some of those activists opposing the occupation and the war in Lebanon.

Influence of the Israeli Women’s Peace Movement

A specifically Jewish women’s peace movement in the United States formed in support of women in Israel organizing against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and in favor of a negotiated settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Israeli Women in Black formed in response to the Israeli government’s reaction to the Palestinian Intifada. A popular uprising in the West Bank and Gaza, the Intifada began December 9, 1987, in response to an incident between a Jewish driver and Palestinian workers. Begun by children throwing stones at Israeli soldiers in the occupied territories, it continued as coordinated strikes in which Palestinian shopkeepers closed stores, and workers periodically stayed away from their jobs within green-line Israel.

When Yizhak Rabin, who was then defense minister, declared an “Iron Fist” policy of “force, might, the breaking of bones” against young Palestinian stone-throwing protesters (a policy articulated and demonstrated on international TV), a group of Jerusalem women dressed in black held a vigil demanding an end to the violence on both sides. They also demanded negotiations between Israel and the PLO toward peace.

The initial Jerusalem vigil—a line of women dressed in black, standing for one hour every Friday, holding banners and placards saying, “Stop the Occupation,” “Stop the Violence,” and “Negotiate”—spread to Tel Aviv, Haifa, and eventually to twenty-four different locations throughout Israel. Within a few months it had spread to the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. In the United States, after the beginning of the Intifada, Letty Pogrebin, Hanan Ashrawi, and others revived the Dialogue Project for mutual understanding.

While for some time North American Jewish visitors to Israel had returned to the United States with concerns regarding the state of perpetual military alert and the militarization of Israeli society, and while some American Jewish travelers had long questioned Israeli governmental policies toward Palestinians, once the Israeli peace movement gained ground, and particularly after the formation of Women in Black, the influence of the Israeli women’s peace movement on North American Jewish women intensified.

Guest lecturers—first Israeli Jews, then Israeli Jews with Israeli Palestinians, and finally Palestinian women leaders from the West Bank—toured the United States, Canada, and Europe speaking before Jewish women’s groups and at synagogues and peace organizations. Among the visiting speakers were Edna Zaretski and Mariam Mar’i, Dalia Sachs and Nabila Espianoli, Alice Shalvi, Zehira Kamal, Naomi Chazan, and Rita Giacomen.

In New York City in April 1988, Clare Kinberg, Irena Klepfisz, and Grace Paley, activists and poets, founded the Jewish Women’s Committee to End the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza (JWCEO). They were encouraged by Lil Moed, an American Jewish feminist who had helped organize a precursor to Los Angeles New Jewish Agenda, then moved to Israel and was active in forming SHANI. Formed “in solidarity with Women in Black and other Israeli and Palestinian women’s groups working for peace,” the JWCEO held weekly vigils, carrying signs and banners similar to those of the Israeli Women in Black, in front of the offices of major United States Jewish organizations and in Jewish neighborhoods.

JWCEO’s aim was “to promote dialogue in the U.S. Jewish community, and to support negotiations between the Israeli government and the PLO toward the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel.” Similar groups formed in twenty-four locations throughout the United States; others were organized in Canada, Italy, Scandinavia, and Australia. Beginning in 1988, the New York JWCEO published Jewish Women’s Peace Bulletin reporting on the activities of the Jewish women’s peace movement in Israel and the diaspora. Jewish women’s peace groups, sometimes calling themselves Women in Black, were active in Boston, Berkeley, Chicago, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, Palo Alto, Santa Cruz, San Francisco, Tucson, Syracuse, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

Although holding weekly vigils was their major activity, both the Israeli Women in Black and their international solidarity organizations engaged in a variety of other political activities. In 1988, when Israeli women organized Women for Women Political Prisoners (WOFPP) to investigate sexual harassment and other forms of mistreatment of Palestinian women prisoners and began a telegram protest campaign, they urged diaspora Jewish groups to transmit the information and send their own telegrams.

Accordingly, in the United States, women from JWCEO, NJA, and the IJPU organized the Human Rights Rapid Response Network to send monthly telegrams to the Israeli government, prison wardens, or the military administration of the occupied territories, in concord with WOFPP and the Israeli Women in Black. In a number of cases the lives of severely ill Palestinian women prisoners were saved by this mobilization of international attention.

Women and Peace Conferences

Demonstrations, retreats, and conferences played a major role in Jewish women’s peace activities, both in Israel and the diaspora. These activities encouraged introspection, consciousness-raising, mutual influence, and public education.

There were four major international women’s peace conferences between 1987 and 1991, and two major nongovernmental international conferences within the United States. Through the four women’s conferences, Israeli and Palestinian women developed an increasing amount of mutual understanding and ability to work together, and Jewish women in the diaspora learned of their work.

The First International Jewish Feminist Conference, organized jointly by Israeli and American Jewish women, brought Jewish women from around the world to Jerusalem in November 1988 to discuss “The Empowerment of Jewish Women.” With the outbreak of the Intifada and the crisis of Israeli governmental policy, members of the planning group split over the question of whether to permit discussion of the effect of the Intifada on women. The newly formed Women in Black and SHANI organized a demonstration at the conference, inviting participants to attend a “Post-Conference,” entitled “Occupation or Peace? —A Feminist Response.”

The Post-Conference included testimony by two Palestinian women from the West Bank about their conditions as women and as Palestinians. This was the first time that most of the participants had heard from Palestinian women directly, and it was the first time that many of the diaspora women met the Israeli women’s peace movement and were able to hear their point of view.

As a result of these conferences in late 1988, Israeli Jewish women began to have greater contact with Palestinian women, both within the Israeli Green Line and in visits to the West Bank and Gaza. They began to plan, in coordination with one of the four major Palestinian women’s organizations, a Women Go for Peace Conference for the following December.

The 1989 Women Go for Peace Conference was significant for several reasons. For the first time, representatives of major Israeli Jewish women’s social service organizations committed themselves to combining the quest for Israeli-Palestinian peace into their program of furthering the status and condition of women in Israel. Also, for the first time, the Israelis shared the podium with leaders of a Palestinian women’s organization. In drawing American and other diaspora women back to Israel for an explicitly women’s peace conference, it furthered their understanding and therefore their work in Jewish women’s peace movements at home.

Coinciding with a major international effort by Peace Now to draw people from around the world to join local Israelis and Palestinians in a “Hands Around Jerusalem” peace chain, it gave the Israeli and Palestinian women’s peace movements worldwide press coverage. Like their international counterparts, American Jewish women returned with reports about the conference, which they shared with other Jewish women at meetings organized by the JWCEO, the NCJW, NJA, and various synagogues and women’s organizations.

The success of the 1989 conference led the Israeli and Palestinian women’s organizations to plan together a Women’s International Conference for Israeli Palestinian Peace for December 1990. Assistance in funding and planning was elicited from Swedish WILPF and from Jewish women’s peace organizations in other countries. American women played an important role.

The process of planning the 1990 conference added three new dimensions to the Jewish women’s peace efforts. (1) Joint planning. Whereas the 1988 Post-Conference had been organized by the Israeli women, with invitations to Palestinian women to participate, and the 1989 conference had been planned separately, with Israelis organizing the morning session and Palestinians the afternoon, the 1990 conference was planned together. The Israel Women’s Peace Coalition (composed of eight different women’s peace groups), the Israel Women’s Peace Network (Reshet), and three of the four Palestinian women’s organizations caucused separately, but the monthly planning meetings were integrated.

(2) Modeling of a conflict resolution process. As the planners put it: “We hope that the 1990 conference, and the process by which we are mutually planning for it, may serve as a model for making peace in the Middle East and as a demonstration of the possibility for a peaceful settlement of the conflict.”

(3) The articulation of a feminist orientation to peace. In contrast with the typical absence of women from official peace conferences, the Women’s International Conference was to demand women’s participation in the peace process, provide women’s perspectives on the issues dividing Palestinians and Israelis (utilization of resources, Law of Return, etc.), and address women’s issues typically neglected in men’s considerations of war and peace, among them the effects of militarization on women’s rights, the relationship between war and the level of sexual harassment, domestic violence, and the many other ways that war differently affects women and men.

The women intended to model and push for actual internationally backed negotiations between the official Palestinian leadership and the Israeli government. Consequently, they wished to have the participation of representatives who were as highly placed as possible. Because it was still illegal for members of the PLO to enter Israel-Palestine, and illegal for Israelis to meet with members of the PLO, a double conference was planned. Part would take place at the United Nations offices in Geneva, Switzerland, and part would take place in Jerusalem.

These plans were interrupted by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990. The resulting war virtually silenced peace groups in Israel. Although both the Israeli and Palestinian women proclaimed that “now, more than ever, we must work for peace,” the war forced the planners to have a much smaller conference in Jerusalem in December and to postpone the Geneva portion of the conference. American Jewish women spoke and observed at the December conference and reported back afterward.

In May 1991, the second half of the Women’s International Conference for Israeli-Palestinian Peace convened at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, attended by seventy-five women from thirteen countries. Among the representatives were members of the European and Swedish parliaments, high-level members of the PLO, six other Palestinians from the territories, and ten Israelis, two of them members of the Israeli Knesset, including Yael Dayan, daughter of the acclaimed Israeli general Moshe Dayan.

Three days of intensive discussion and negotiation produced a three-page consensus document covering most of the major issues in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The document called for official negotiations, regional security and arms control, human rights, and attention to the economic and social consequences of the occupation. “We are women talking to each other while war is going on between our two peoples,” said the PLO ambassador in her closing remarks. “It is very important for our people to know that we can meet together to work for peace.”

News of the Geneva conference was transmitted by the participants and observers returning to their countries, in the form of speeches (primarily before women’s organizations, including JWCEO, the National Jewish Women’s Resource Center, the American Association of University Women, NJA, and various synagogues), radio programs such as Pacifica KPFA, and articles in such journals as Bridges and New Directions for Women.

The conference coincided with U.S. Secretary of State James Baker’s as yet fruitless efforts to get Israel and the Palestinians to agree on terms for an international peace conference. Four months later, an official international peace conference began in Madrid, Spain, with Israeli and Palestinian participation. Women in Black as a symbol and activity of women’s direct action for peace was adopted by Serbian women protesting the war in Bosnia and by American women expressing their support for the victims of that war. It became an international symbol and resource for women’s work for peace.

Women in Black held their vigils week in and week out for nine years, from the beginning of the First Intifada to the promised peace of the Oslo Accords. And although the inherent flaws of the Oslo Accords were obvious to many of them, they stopped vigiling, only to be brought back to the streets with the second Intifada.

By the year 2000, seven lean years of the Oslo peace Accords had doubled the number of Jewish settlements on Palestinian land in the West Bank and Gaza. Bypass roads for Israeli Jews (only) carved up the territories—the land of the Oslo-promised Palestinian State—into a Swiss cheese of Israeli settlements and bypass roads guarded by more and more Israeli soldiers. The importation of Russian Jews and foreign workers, and the exclusion of Palestinian laborers from their former jobs within Green-Line Israel, (border before June 10, 1967) plunged the Palestinian economic situation into ever more desperation. When Ariel Sharon, accompanied by 1500 Israeli police, took his controversial and provocative Jerusalem walk to the Moslem holy places, Palestinians erupted, and the second Intifada began.

With the second Intifada, Women in Black resumed their vigils, and joined Bat Shalom, Tandi, Israeli branch of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and other organizations in forming the Coalition of Women for a Just Peace, an umbrella group of “Jewish and Palestinian women (all citizens of Israel) ... calling for peace and justice for all inhabitants of the region.” In March 2001 they were joined by Machsom Watch, and later by “The Fifth Mother,” and “New Profile.”

Machsom Watch

Machsom (or checkpoint) Watch is an organization of women who monitor military and police behavior at checkpoints. The Israeli government justifies the checkpoints it has set up throughout Palestine as necessary to protect Israelis against suicide bombers. Most of these checkpoints, however, are not at the borders with Israel, but within Palestinian territories. They separate Palestinians not, primarily, from Israel, but from their lands, livelihoods, schools, jobs, and each other. At the checkpoints, young Israeli soldiers have the power to decide whether sick Palestinians can get to a hospital, whether teachers can get to work, whether children can get to school, or parents can pick them up. Several Palestinian women have had to give birth on the ground at checkpoints, because soldiers would not let them pass to go to a hospital. Many mothers and new-borns have died. Waiting for permission to pass through checkpoints, Palestinians are subject to humiliation, derisive laughter, and physical abuse. An ordinary fifteen-minute trip can take hours.

Two Israeli organizations have responded specifically to the problems at checkpoints: Btselem, the [gender-mixed] Israeli Human rights organization, and Machsom Watch. Begun by three women in 2001, Machsom Watch now has 400 women who show up at checkpoints throughout the country “to monitor the behavior of soldiers and police; to ensure that the human and civil rights of Palestinians attempting to enter Israel are protected; to record and report the results of [their] observations to the widest possible audience, from the decision-making level to that of the general public.” Mostly made up of “mature professional women,” they attempt to exert a chastening moral influence on militarized young men.

“The Fifth Mother” calls for involving conflict resolution experts to break the impasse in negotiations for peace. They also focus on eradicating military language from public discourse, a concern they share with “New Profile.” The latter organization aims at the demilitarization of Israeli society in education, discourse, and practice:

We support the right to resist the draft, conscientious objection, and refusal to serve in the Occupied Territories for all men and women. We work with women whose lives have been damaged by militarization, such as victims of sexual harassment in the military, or of exploitation by the Ministry of Defense.

In addition to its activist activities, often in coordination with such gender-mixed organizations as Gush Shalom, Palestinian non-violent activist organizations, and the International Solidarity Movement, The Coalition of Women for a Just Peace supports scholarly studies, such as the two most recently posted on its website (www.coalitionofwomen.org) on the impact of the armed conflict on women within Israel and the Occupied Territories.

Continuing their long tradition, begun in 1988, of international conferences for Israel/Palestine peace, Women in Black held their latest conference, called "Women Resist Occupation and War" in Jerusalem from August 12 to 16, 2005. While the 1991 Geneva conference had drawn 75 women from 13 different countries, the 2005 conference drew over 650 women from 44 countries. As in the previous conferences, the conference was planned jointly by Israeli and Palestinian women. They faced formidable obstacles:

Since there is no movement of Women in Black in Palestine, and since the Israeli army prevents us from entering each other's areas (only internationals are allowed to cross), there were great difficulties in trying to plan this together. Nevertheless, both sides were committed to coordinating the planning and implementation of the conference. Palestinian women also conducted the solidarity visit in the occupied territory.

Each of the workshops related to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict was co-facilitated by a Palestinian and an Israeli. In addition, the conference addressed “Women’s Global Challenges,” among them War Crimes against women, domestic violence, effects of globalization and privatization, and “The Politics of Fear, Hatred, and Racism.”

A major point of contention—the insistence by Palestinian women that a workshop on lesbianism be canceled—sparked concerted discussions of the interrelationships among patriarchy, homophobia, and other forms of oppression, including the Occupation. The controversy continued beyond the conference itself. Given the important role of lesbians in organizing for peace and women’s rights, it is likely to promote further efforts at resolution.

As befits a conference of activists, 200 international participants joined the Friday Women in Black vigil in Jerusalem, and the Conference ended with a demonstration at the Kalandia checkpoint.

In 2005 there are almost 400 Women in Black vigils in 37 different countries, from Belgium to Bahrain, from Australia to the United Kingdom. The international movement of Women in Black was honored with the Millennium Peace Prize for Women, awarded by the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) in 2001. The international movement, represented by the Israeli and the Serbian groups, was also a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001. Israeli Women in Black won the Aachen Peace Prize (1991); the peace award of the city of San Giovanni d’Asso in Italy (1994); and the Jewish Peace Fellowship’s “Peacemaker Award” (2001).

In the USA, there are vigils in multiple locations within each of forty of the fifty states. In addition to participating in Women in Black vigils, U.S. Jewish women have led other organizations dedicated to Israeli/Palestinian peace. For example, Marcia Freedman, who had, as a member of the Israeli Knesset advocated a “two-state solution” to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as early as 1975, heads “Brit Zedek V’Shalom, ‘the Jewish Alliance for Justice and Peace... a national organization of American Jews deeply committed to Israel's well-being through the achievement of a negotiated settlement to the long-standing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.” Barbara Lubin and Penny Rosenwasser lead The Middle East Children’s Alliance, “A non-governmental organization working for peace and justice in the Middle East, focusing on Palestine, Israel, Lebanon and Iraq... [with special emphasis] on the rights of children.”

For almost a century, Jewish women have continued to participate in peace movements, working for peace with justice in Israel/Palestine, in Iraq, and wherever war and oppression threaten human life.

Adams, Judith Porter. Peacework: Oral Histories of Women Peace Activists (1991).

Balka, Christie, and Reena Bernards. “Israeli and Palestinian Women in Dialogue: A Model for Nairobi. New Jewish Agenda’s Role at the UN ‘Decade for Women’ Conference Forum ’85 in Nairobi: Final Report.” 4107 v.f. Jewish Women’s Resource Center, National Council for Jewish Women, NYC.

Beck, Evelyn Torton, ed. Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology (1982. Revised and expanded 1989).

Brettschneider, Marla. Cornerstones of Peace: Jewish Identity Politics and Democratic Theory (1996).

Bulkin, Elly. “Hard Ground: Perspectives on Jewish Identity, Racism, and Anti-Semitism.” In Yours in Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Anti-Semitism and Racism, edited by Elly Bulkin, Minnie Bruce Pratt, and Barbara Smith (1984).

Chazan, Naomi. “Israeli Women and Peace Activism.” In Calling the Equality Bluff: Women in Israel, edited by Barbara Swirski and Marilyn P. Safir (1991).

Degan, Marie Louise. The History of the Women’s Peace Party (1939).

Espanioli, Nabila, and Dalia Sachs. “Peace Process: Israeli and Palestinian Women.” Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends 2 (1991): 112–119.

Falbel, Rita. “Jewish Women.” New Directions for Women (March/April 1989), and “Women’s Vigil Against the Occupation.” Genesis 19, no. 2 (Summer 1988): 7.

Falbel, Rita, Irena Klepfisz, and Donna Nevel. Jewish Women’s Call for Peace: A Handbook for Jewish Women on the Israeli/Palestinian Conflict (1990).

Foster, Catherine. Women for All Seasons: The Story of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (1989).

Freedman, Marcia. Exile in the Promised Land: A Memoir (1990).

Gorelick, Sherry. “The Changer and the Changed: Methodological Reflections on Studying Jewish Feminists.” In Gender/Body/Knowledge: Feminist Reconstructions of Being and Knowing, edited by Alison M. Jaggar and Susan R. Bordo (1989), and “Doing the Impossible for Peace.” New Directions for Women 2, no. 5 (September/October 1991), and “Geneva Conference: History and Goals.” Bridges 2 (1991): 120–123.

Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie, and Irena Klepfisz, eds. The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology.

Klepfisz, Irena. Dreams of an Insomniac: Jewish Feminist Essays, Speeches and Diatribes (1990).

“An Open Letter to Women Attending the American Jewish Congress Conference ‘Empowerment of Jewish Women’ from SHANI—Israeli Women Against the Occupation.” #4288. Jewish Women’s Resource Center, National Council for Jewish Women, NYC.

Pogrebin, Letty Cottin. “Anti-Semitism in the Women’s Movement” Ms. (June 1982, and see “Letters Forum: Anti-Semitism” in the February 1983 issue for responses). (Reprinted in Eye 9, no. 2, March 1983), and Deborah, Golda and Me: Being Female and Jewish in America (1991), and “Going Public as a Jew: How I Was ‘Born Again’ to My Own People.” Ms. (July/August 1987).

The Road to Peace: Israeli-Palestinian Dialogue in New York. Special edition, New Outlook 32, no. 3–4 (March–April 1989).

Rogow, Faith. Gone to Another Meeting: The National Council of Jewish Women, 1893–1993 (1993).

Swerdlow, Amy. Women Strike for Peace: Traditional Motherhood and Radical Politics in the 1960s (1993).

Sharoni, Simona. Gender and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Politics of Women’s Resistance (1995).

IN POSSESSION OF THE AUTHOR

“Final Document.” Women’s Geneva Conference for Israeli-Palestinian Peace. Palais des Nations, Geneva, Switzerland, May 13–15, 1991. 3 pages.

Sachs, Dalia. Speech given (in Hebrew; English translation by its author) at the panel on women and their contribution to peace. Women Go for Peace Conference, Jerusalem, Israel, December 29, 1989.