Architects in Palestine: 1920-1948

The mass immigration from Europe after 1933 brought many architects to Palestine, amongst whom were a number of women. For these women, being an architect meant total devotion to the profession. Four of the most influential female architects of the time were Lotte Cohen, Elsa Gidoni-Mandelstamm, Genia (Eugenie) Averbuch, and Judith Stolzer-Segall. Each of the female architects working and living in Palestine reveals something about women’s life and work.

Resettlement of Jewish Palestine started at the end of the nineteenth century (1882) as a result of the pogroms in Eastern Europe and the emerging Zionist Movement. In the main, agricultural settlements with standard houses were built and few representative buildings, such as synagogues, were constructed. Most of the architectural design and work was carried out by non-Jewish architects and builders. The Ottoman government, headquartered in Constantinople, had no building regulations comparable to Western standards. The situation changed after World War I with the declaration of British Mandatory Palestine, when European architects were allowed to use and display their professional abilities. British building projects blossomed and paved the way for the Zionist Movement to realize its aims.

The mass immigration from Europe after 1933 brought many architects, amongst whom were a number of women.

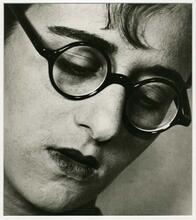

Lotte Cohn

The first was the Berlin-born Lotte Cohn (1893–1983), one of the few women architects in Germany. Her father, Dr. Bernhard Cohn (formerly Rachmiel) (1841–1901), was born in Nakel (now Nakło nad Notecią) in the province of Poznań studied medicine in Berlin, and was for nearly a quarter of a century the only doctor in the suburb of Steglitz. A co-founder of the Berlin branch of the Zionist Organization, he published Before the Storm in March 1896, one month after the publication of Herzl’s The Jewish State, which expressed similar ideas though the authors did not know each other.

Circa 1877, after his first wife had died in childbirth, he married Cäcilie Sabersky (born c. 1852 in Zossen, Brandenburg). In addition to Lotte, they had four children: Max David (b. 1878); Emil Moses (1881–1948), a rabbi and writer, who published under the pseudonym Emil Bernhard; Helene Hinde (1882–1996), who emigrated to Palestine in 1921, together with Lotte; Elias (1884–c. 1910); and Rose Lea (b. 1890), who was the first to emigrate to Palestine, in 1920, worked at the Jewish National Fund and wrote the German correspondence for its then-director, Menahem Ussishkin.

After receiving her diploma in 1916 from the Institute of Technology in [Berlin-] Charlottenburg, Lotte Cohn’s first task was helping to rebuild Eastern Prussia, damaged by the war. Invited by the Zionist Organization and encouraged by her father, she arrived in Palestine in 1921 and was the “first assistant” of Richard Kauffmann (1887–1958), responsible for planning most of the settlements founded before 1948. She worked for the PLDC (Palestine Land Development Company) until 1927. She was involved in the general planning of A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim, including En-Harod, Tel Yosef and Ginnegar, and also in creating settlement housing and children’s houses for kibbutzim. Cohn built some private homes, as well as the Agricultural Girls’ School in Nahalal (1923). She participated in architectural competitions, e.g., Central Zionist Buildings in Jerusalem (1927) and a Home for the Aged, Ramot ha-Shavim (1937). Her building style is functional and modest for ideological reasons; her houses for agricultural settlements have tiled span-roofs, familiar to the new immigrants of European origin.

The experience Lotte Cohn gained in rebuilding Eastern Prussia with agricultural buildings and low-budget houses provided her with the basis for further planning and building in Palestine. Never interested in modernist stylistic issues, she nevertheless gave adequate forms to her designs and resolved functional problems, in both the private and public domain. During the years 1931–1969 she had her own studio in Tel Aviv and from 1952 shared it with Yehuda Lavie (Ernst Levinsohn). Erudite, vivacious and modest, Lotte Cohn was a prolific writer, who expressed her appreciation of her first master Richard Kauffmann by writing articles about him and his unique work. She was a typical example of a courageous pioneering architect, whose work did not achieve the recognition it deserved.

Elsa Gidoni-Mandelstamm

Fewer personal and professional details are known about another pioneering woman architect and interior designer, Elsa Gidoni-Mandelstamm (1901–1978), who was born in Riga (Latvia) and studied architecture at the same Institute of Technology in [Berlin-] Charlottenburg as Lotte Cohn. She had her own architectural firm in Berlin from 1929 until emigrating to Palestine in 1933. Involved in building projects for young pioneer women such as Beit ha-Halutzot in Tel Aviv, she also planned apartment houses, the Swedish Pavilion at the Levant-Fair (1934) in Tel Aviv and, together with Genia (Eugenie) Averbuch, the Café Galina, which are all examples of the progressive “International Style.” The buildings have cubist shapes, flat roofs, characteristic horizontal windows and smooth mortar walls.

Elsa Gidoni, as she is known, was a modest and politically engaged woman architect. She lived and worked in Tel Aviv until moving to New York in 1938. In the United States she designed the General Motors Futurama pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair and later worked in the architectural firm of Kahn & Jacobs.

Genia (Eugenie) Averbuch

Gidoni’s co-worker at the Levant-Fair, Genia (Eugenie) Averbuch (1909–1977), was born in Semlia, Russia but came to Palestine with her parents as a two-year-old child. Her father was a pharmacist. In World War I she and her family were expelled to Egypt. After completing school at the Herzlia Hebrew Gymnasia in Tel Aviv at the age of seventeen, she left for architectural studies in Rome and Brussels (1927–1930). Immediately after the completion of her studies at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts she returned to Palestine. Initially, she had an architectural firm in Tel Aviv together with the architect Shlomo Ginsburg (1906–1976), nicknamed Sha’ag, to whom she was briefly married in 1933. (She later married Chaim Alperin, a police officer, by whom she had one son, Daniel.) Her name is still connected to the design of the most famous square in Tel Aviv, which was planned in its urban form by Sir Patrick Geddes in 1925. The final design of the so-called “Zina Dizengoff Circle” was the result of a competition which she won in 1934. She proposed a uniform façade design for all the three-story buildings around the circle, despite their functional differences. The horizontal movement of her design is emphasized by continuous concrete strips that either form balcony parapets or are applied without any function. This circle, despite the massive deformation it underwent, is until today the heart of Tel Aviv, in which six streets converge.

At the same time, the Levant Fair was held, where Genia Averbuch, Elsa Gidoni and Sha’ag together designed the interesting round-shaped Café Galina.

The Levant Fair was one of the agents that drove Modern architecture in Palestine from the intellectual avant-garde into the acknowledged mainstream. The enthusiasm that the exhibitions caused spread, and included in its wake the eager acceptance of the new architecture by the public, beginning the transformation of Tel Aviv into the “white city” that several Modern Movement historians consider unique (Schwartz et al.).

Genia Averbuch worked in the private domain during the 1930s, but decided after World War II also to contribute to the public one. From 1945 to 1948 she worked as town planner for the Tel Aviv township. Her impact on very typical Israeli institutions is noteworthy. She planned some of the most important youth villages, such as that of the religious Kefar Batya (1945) and Hadassim (1947) in the Sharon region and a synagogue on A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Ein ha-Naziv. She also built some important schools: the Max Fein vocational school (1949) in Tel Aviv and religious high schools in Kefar Sava and Pardes Hannah. Apart from the quantity of her buildings of various types, it is their stylistic quality which makes Genia Averbuch one of the leading architects in Israel. But except for her design of the Dizengoff Circle, her work has not been adequately researched or appreciated.

Judith Stolzer-Segall

The three female architects referred to above were all involved in pioneer projects and personally dedicated to the Zionist Movement and its ideas. In contrast, the life and work of Judith Stolzer-Segall (1904–1990) is a typical example of a refugee, migrating from place to place, feeling cosmopolitan, communist, and humanist, for whom her Jewishness was a burden and who, in consequence, never took roots in Palestine. Nevertheless, her contribution to Israeli architecture is important, despite the relatively few, though quality, buildings she designed. She won two competitions and executed them. Her design for the Kiryat Meir neighborhood in north Tel Aviv (named after the city’s legendary mayor, Meir Dizengoff), with approximately 170 two- and three-room apartments, received compliments for its well-planned and spacious kitchens. Segall arranged the rows of houses in a parallel manner, as was common in the most progressive mass-housing projects in Europe. The houses also have spacious balconies, meant for use in the hot season. Flat roofs, smooth plaster and pilotis (stilts) reveal the connection to the International Style.

The prize she won in the competition for the Great Synagogue in Haderah (1937) surprised both the architect and the client. Judith Segall appears to have been the first female architect who ever designed and built a synagogue and the objecters were won over when made aware of the deep Jewish roots and tradition of her family. The synagogue is in any case a very original and impressive concrete structure on the top of a hill next to the historic khan (caravansary) building, now transformed into the local museum. The broad-storied synagogue rises upwards and ends in a wide central tower, giving the impression of a fortress, and the small half-rounded openings in this tower were interpreted as embrasures—not surprisingly, given the riots in 1936.

The trade union building in Jerusalem planned by Judith Stolzer-Segall and executed together with her Hungarian-born husband, Dr. Eugen Stolzer (1886–1958), remains an excellent example of the official building trend in 1950s Israel. It is a multipurpose complex with harmonious proportions, representing the modest language of the so-called Functionalist Style. The dedication of the building was not only an architectural event but also a social and political one, expressing the role of the trade union at that time. For the Stolzer-Segall couple, the money they earned after a long period of financial hardship gave them the possibility to travel to Europe and the cultural background they so sorely missed. Dr. Eugen Stolzer died on this trip and Judith Stolzer-Segall looked for a quiet place where she could live in peace; she never returned to architecture but instead engaged in social and intellectual pastimes. She died in a Jewish old people’s home in Munich in 1990, totally forgotten as an Israeli architect. Thanks to a suitcase containing numerous personal documents found after her death, her restless life could be partially reconstructed.

Each of the female architects working and living in Palestine reveals something about women’s life and work; it does not seem to be accidental that two of them remained unmarried, one married late in life and one was married for only a brief period. Only one had a child. In this period being an architect meant total devotion to the profession.

Elhanani, Aba. The Struggle for Independence: Israeli Architecture in the Twentieth Century. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense Edition, 1998.

Frenkel, Eliezer. Chronology. Art History, History of Architecture, Design, Sculpture, Painting (Hebrew). 2 vols. 2nd edition. Tel Aviv: Sadna College of Architecture, 1996.

A general book of art and architecture, devoting a large amount of space to Israeli artists and architects. It is an educational book/textbook, based on various sources and also on personal interviews. This book gives the most detailed information regarding female architects.

Metzger-Szmuk, Nitza. Des maisons sur le sable. Tel Aviv. Mouvement moderne et esprit Bauhaus. Tel Aviv: 1994.

Idem. Dwelling on the dunes. Tel Aviv. Modern movement and Bauhaus ideals. Paris, Tel Aviv: Editions de le’éclat, 2004.

Meyer-Maril, Edina. “What Do a Suitcase in an Old-Age Home and the Haderah Synagogue Have in Common? The Life’s Work of Architect Judith Segall-Stolzer (1904–1990)” (Hebrew). Considerations in Keeping of Archives 4 (2003) 8–12.

Idem. “The Great Synagogue in Haderah.” In Haderah: A Hundred Years and More (Hebrew), edited by Nina Rodin and Aryeh Amir, 76–82. Jerusalem: 1993.

Nerdinger, Winfried, ed. Tel Aviv: Modern Architecture 1930–1939. Photographs Irmel Kamp-Bandau (exhibition catalogue). Tübingen, Berlin: Wasmuth, 1994.

Schwartz, Horacio, Arieh Sivan, Raquel Rapaport. When Camels Fly: The Levant Fair of 1934, Tel Aviv. http://www.archi.fr/IFA/sitedoco/gb/183a.htm [28.9.2004].

Stratigakos, Despina. “Reconstructing a Lost History: Exiled Jewish Women Architects in America.” Aufbau (The Transatlantic Jewish Paper) 68 (2002): 14.

Wahrhaftig, Myra. Sie legten den Grundstein: Leben und Wirken deutschsprachiger jüdischer Architekten in Palästina 1918–1948. Tübingen, Berlin: Wasmuth, 1996.

A survey of German-speaking architects active in British Mandatory Palestine, presented as a collection of biographies, accompanied by photos, drawings and plans. The only book on this topic which includes female architects.