Charlotte Charlaque

Charlotte Charlaque was a German-American actress, translator, teacher, singer, dancer, violinist, and receptionist at Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin. She became one of the first transgender women to receive gender-affirmative surgery at the Institute in the 1930s and helped other transgender patients at the institute. In exile after 1934, she lived in the Czech Republic with her friend and lover, artist Toni Ebel. Charlaque escaped to New York City in 1942 and was known lovingly and locally as the “Queen of the Brooklyn Promenade.”

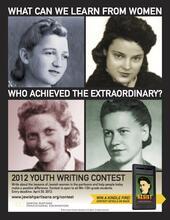

Introduction

Charlotte Charlaque had to present her story many times to various authorities to access healthcare and escape violence. Her story changed with each telling, and she left no memoir. Instead, she left her letters, her correspondence with doctors and officials, mentions in newspapers, and an article she wrote in 1955 in which she boldly states that transgender people are nothing new. In her 30s she found community at the Magnus Hirschfeld Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin, where she developed relationships with other transgender women such as Toni Ebel and Dora Richter. Her life’s journey crisscrossed the Atlantic several times in search of freedom and safety, arriving finally in 1942 in New York City, where she spent her later years as a beloved member of the queer and artistic theater scene.

Charlaque went by many chosen names and spelling variations at different points in her life, including Lola Sharlach and Charlotte Curtis. While she used different names to protect herself from antisemitism, classism, and transmisogyny, some of these names might have been just for fun, such as Baroness Carlotta von Curtius, which she used in her later life; she was, of course, not descended from nobility despite her royal personality.

Early Life and Family History

Charlotte Charlaque was born in Schöneberg (now a borough of Berlin) on September 14, 1892, the second child of Jenny Adelheid [May] Scharlach (1861-1927) and Edmund Scharlach (1857-1935). Her family were German-Jewish textile merchants. In the summer of 1901, the family moved to San Francisco. While in the United States, Charlaque’s parents divorced; following the divorce and with Adelheid ailing, Charlaque’s mother and brother returned to Germany in 1910, with Charlaque remaining in the United States. As of 1916, she was living in Chicago studying the violin and singing; in 1917 she moved to New York.

While in the United States, Charlaque corresponded with Dr. Harry Benjamin, a pioneering Jewish German-American sexologist (1885-1986), seeking gender-affirming care. She also met with him in person at least two times around 1920 in New York City. Benjamin denied her request but suggested she visit his colleague Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935), a Jewish sexologist, doctor, author, and advocate for LGBT and women’s rights, in Berlin. In 1922, after hearing that her mother’s illness had progressed and after Benjamin’s referral to the Institute for Sexual Science, Charlaque moved back to Germany.

Life in Berlin

In 1920s Berlin, Charlaque, who went by the name of Lola Charlaque until around 1932, found work singing, acting, and dancing. Around 1925 she started working at the Institute for Sexual Science run by Magnus Hirschfeld, which operated from 1919 to 1933. Four stories high, the Institute had a sex museum, medical rooms, places for counseling, living quarters, a ballroom and dining area, and an invaluable library. During this period Berlin was an oasis for queer, gender-nonconforming, and transgender people. There was a bustling nightlife scene and specialty magazines and bars for different queer identities. The Institute’s importance and its location in Tiergarten cannot be overstated as the focal point for both science and culture; the Institute was where many queer and/or trans people found peace and safety through gender transition, affirmative counseling, community, and events.

Charlaque filled various roles at the Institute. She was a receptionist at the front desk and assisted in giving directions to and translating for visitors. She advised transgender patients on what fashions to wear and assisted them in finding apartments. She traveled as a translator with Dr. Felix Abraham (1901-1937), a Jewish sexologist and doctor connected to the Institute, Karl Giese (1898-1938), one of Hirschfeld’s life partners and the Institute’s archivist, and Hirschfeld to the Third International Congress of the World League for Human Rights in London in 1929. She most likely had a Transvestitenschein, a rudimentary transgender identification card.

Most likely in early 1928, Charlaque met Toni Ebel (1881-1961), a painter of landscapes, still lifes, and portraits, and the two quickly became friends and lovers. Charlaque suggested Ebel seek support at the Institute, where she was given accommodation and hired as a housemaid; after receiving gender-affirming care, Ebel continued to work at the Institute. Charlaque was also friends with Dora Richter (1892-1966), a lacemaker, maid, and cook at the Institute. In the 1933 Austrian film Mysterium des Geschlechts (Mystery of Gender), Richter, Ebel, and Charlaque appear together, briefly smiling at each other and the camera.

In the early 1930s, Charlaque received what we now call gender-affirming surgery, becoming one of the first trans women in European recorded history to receive a vaginoplasty. As the clinic at the Institute in Tiergarten served mostly as a location for pre and post-operative care, Charlaque’s several surgeries were conducted by doctors at other hospitals.

After 1933

By about 1933, Charlaque and Ebel were living together in Schöneberg. The same year Ebel completed her conversion to Judaism. On May 6, 1933, the Nazis raided the Institute for Sexual Science, and four days later they burned and publicly destroyed documents, photos, magazines, paintings, and books from the Institute at Opernplatz (today Bebelplatz) in the first Nazi book burning. The library of the Institute was the first place the Nazis raided and destroyed and burned books because of Hirschfeld’s identity as a gay Jew, what the Institute represented, and its wealth of queer knowledge.

Despite the Nazis’ rise to power, trans people continued on with their lives, albeit in increasingly difficult circumstances. In a 1933 article about the status of trans people in Berlin, Swedish journalist Ragnar Ahlstedt (1901-1982) describes a night shared with Charlaque, Ebel, and their friends Fritz and Felicitas. The evening begins at an Italian restaurant and ends with Toni serving tea and Charlaque playing the violin and dancing for the group at their flat. Charlaque shared that she wished to give birth to a child and was upset that Lili Elbe’s (1882–1931) uterus transplant operation had been unsuccessful (Ahlstedt, 8-13).

Exile

With the support of the Jewish community and advice from Ebel’s sister, Charlaque and Ebel escaped Berlin for Czechoslovakia in May 1934. It is not known the level of “out” Ebel and Charaque were in their Jewish circles, but they were not the only people connected with the Hirschfeld Institute who were aided in their escape from Germany by their Jewish community. A noteworthy example is Karl M. Baer (1885-1956); the director of the B’nai B’rith Lodge in Berlin, Baer was a social worker, feminist advocate, and intersex individual who wrote a memoir titled “Aus eines Mannes Mädchenjahren” (“Memoirs of a Man’s Maiden Years”).

Living in Karlsbad (now known as Karlovy Vary), Charlaque tutored Jewish refugees in English, French, and German, while Ebel painted portraits of spa guests for money. The area was popular with German-speaking refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. Charlaque and Ebel likely also reconnected with their friend Dora Richter, who had been born in Bohemia and previously lived in the area. While living in Czechoslovakia, Charlaque started to use the name Charlotte.

In November 1936, the couple settled in Brno, explaining to authorities they had to live together because Ebel was sick and Charlaque was her caretaker. Authorities were suspicious of them, possibly assuming they were spies because they were German. In Brno, Charlaque presumably tutored Karl Giese in English, preparing him to emigrate. He discussed his writings about Hirschfeld with Charlaque a few days before he died by suicide on March 1, 1938.

In 1938 Ebel’s German passport expired. Toni Ebel later recalled that their house was frequently searched and they were forced to report regularly to the police. Fortunately, a student of Charlaque’s worked at the German consulate and was able to obtain a new passport for Ebel at the end of 1938. Needing papers after the German invasion, Charlaque was given a temporary Czechoslovakian passport under the name Charlotte Scharlachova. In order to conceal her identity, she told Czechoslovakian authorities that she had been born in the town of Moravian Schöneberg in the Czech region of Moravia [Sumperk in Czech] and was Catholic, presumably out of fear of being outed as Jewish or transgender. This temporary passport expired in 1940.

Charlaque and Ebel left Brno for Prague in March 1939, hoping it would be safer there. Charlaque taught acting and translated three works by the Czech writer Olga Scheinpflugova (1902-1968) into English. In her later years, Charlaque said she provided language tutoring to Jewish refugees in Prague, and she and Ebel helped some escape continental Europe.

Red Cross document attesting that Miss Charlotte Charloque was living in good health in New York, August 25, 1943.

Source: War Time Card File (Registration cards, employees; record books, individual correspondence A-Z, 02020201 oS, 71764056, ITS Digital Archive, Arolsen Archives.

In the summer of 1940, Charlaque applied for residency in Prague, but officials were suspicious of her; not only was she Jewish and thus had lost her German citizenship because of the Nazi racial laws, but they may also have disapproved of her tutoring other refugees. In March 1942 she was arrested by the Prague Immigration Police. Ebel followed the police officers who took Charlaque and convinced the Swiss Embassy in Prague—acting as deputy for the American Embassy—that Charlotte was an American citizen and had the documents to prove it in Vienna, blaming Austria’s slow bureaucracy and unwillingness to forward the documents. Whether or not this story was true is unclear, but through it, Ebel saved Charlaque from deportation. Charlaque was sent to the Liebenau internment camp, close to the Swiss border in southern Germany, 290 miles from Prague. It was here that non-German women and children from Nazi-occupied territories were exchanged for German prisoners held by the United States and Britain. In May 1942, via a letter from the Red Cross in New York City, Ebel learned that their plan had worked and Charlaque would be taken to the United States.

New York City Years

After sailing from Lisbon, Charlaque arrived in New York City via Ellis Island in July 1942, twenty years after she had returned to Germany. Ebel intended to follow but was not given a visa. She missed Charlotte greatly, writing: “It was impossible for me to work for days, my sweetheart was no longer with me” (handwritten personal history by Toni Ebel). In September 1943, Ebel learned via the Red Cross that Charlaque was living in good health in New York. Charlaque and Ebel never reunited, but they corresponded for several years at least.

After Charlaque arrived at Ellis Island, the Red Cross took her to a poor house until she moved to Greenwich Village. Since she no longer had any American papers, it is assumed that she established some contact with family members living in the United States that enabled her to stay, or she told officials to look for her proof of citizenship in the United States records. It is still unknown what she was able to save and bring with her to America; she probably had no past papers, and it could have been dangerous if she shared or kept any documentation from the Hirschfeld Institute such as her Transvestitenschein. Documentation from the Red Cross used the name “Miss Charlotte Charlaque,” indicating that her name and gender were recorded correctly in New York (Arolsen Archives).

By the end of 1942, Charlaque was already gracing the stages, appearing at the Village Art Theater with a “night of Continental drama” (New York Post, December 19, 1942). An advertisement in a German-language Jewish newspaper included her as a featured performer for the “Best International Folk Art” at the Continental Club and Restaurant on Sullivan Street (Aufbau September 29, 1944). Here she was accompanied by a fellow Jewish German refugee, the composer and pianist Fred Sigismund Witt (1898-1946). Rents were high; Charlaque received welfare but had very little money to spare. One day she fainted on the street and was taken to the hospital, where the doctor recommended that she secure a job where she did not need to do heavy labor. She worked as a translator and as a switchboard operator for a New York hotel.

Contact with Prominent Transgender Figures in the United States

In a 1955 article for the homosexual periodical ONE magazine titled “Reflections on the Christine Jorgenson case,” Charlaque commented that being transgender and receiving gender-affirming surgeries was not new. Although she did not identify herself as transgender, she cited her time at the Institute for Sexual Science and her association with Dr. Hirschfeld and mentioned four people she knew who had surgeries before 1935. (Jorgenson [1926-1989] was a famous transgender singer, writer, activist, and World War II veteran.) Charlaque wrote: “Miss Jorgenson was neither the first nor will she be the last to undergo such an operation” (Baroness von Curtius, March 1955). In private letters to Jorgensen, Charlaque introduced herself and said they had similar lives and histories and should become acquainted; eventually, they met in person. Charlaque was also in contact with Louise Lawrence (1912-1976), a transgender activist and writer who worked with sexologist Dr. Alfred Kinsey (1894-1956) in California. She proposed splitting the costs for a road trip from the East Coast to California but Lawrence declined.

Declining Health and Death

Charlaque had many health struggles. She had an inflamed gallbladder and stomach ulcer and could not write long letters due to a tremor, which likely started in the late 1940s. Eventually, she was let go from work due to her chronic illness. Charlaque wanted to move back to Germany but was afraid of the still prevalent antisemitism (Charlaque to Ebel, June 24, 1947). She wrote to Ebel that she had no one to talk to about things that mattered to her in New York City (Charlaque to Ebel, October 18, 1946). In 1959, however, she found her community at the Chamber Theater in Brooklyn. In February 1960, when she appeared in Mademoiselle Colombe, “The Brooklyn Heights Press drama critic reported that: Mme Georges, played by Lotte Curtius, stole and enlivened the scenes in which she appeared” (Rustin, February 14, 1963).

In 1961 Charlaque had two heart attacks and moved into a hotel on Pierrepont Street. She died at age 70 on February 6, 1963 (the 12th of Shevat, according to the Hebrew calendar). Her official funeral service was a few days later. Another memorial was held at a friend’s house in Garden Place. Her friends donated to start a library memorial fund in her name and to cover the cost of her funeral service and cremation; they also scattered her ashes at the Brooklyn Promenade, where she had so often walked with an air of wisdom in her fabulous purple attire, earning her the nickname “Queen of the Promenade.” Richard Rustin wrote in his front-page obituary for Charlaque in the Brooklyn Heights Press: “The curtain for the queen may have fallen but her audience has not forgotten” (Rustin, February 14, 1963).

Post Mortem

Currently, new files and information about Charlaque are being found frequently. The Magnus Hirschfeld Society, located in Berlin around the corner from where Charlaque lived, has a library and journal in which discoveries are celebrated and shared with a broader audience. In 2021, Raimund Wolfert published a German-language biography of Charlaque. In 2022, Wolfert and Esra Paul Afken created an exhibition and website about Ebel’s life at the Sonntagsclub in Berlin. In the 2023 film Eldorado – Everything the Nazis Hate, Eli Kappo portrayed Charlaque, smoking in a bar and dancing with Ebel. In late 2023 Charlaque was honored with an entry in the NYC LGBT Historic Sites project. In early 2024 Phillip Gufler exhibited a quilt dedicated to Charlaque in Potsdam, and a musical about her is being produced by a team in Berlin, New York, and Vienna. Charlotte Charlaque was also the great-aunt of Ari Wolf, who continues to celebrate her legacy and write about her.

Thanks to Mara Portner, Alma Roggenbuck, Ari Wolf, and Raimund Wolfert for editing assistance and insights.

Afken, Esra Paul, and Wolfert Raimund. “Toni Ebel 1881–1961 Painter – a Search for Clues.” November 4, 2022. https://toni-ebel.de/.

Ahlstedt, Ragnar. “Men who became women. Two interesting cases of gender reassignment by operative route. Few observations to illuminate the essence of transvestism (Män, som blivit kvinnor. Tvà intressanta fall av könsväxling pà operativ väg. Nägra iakttagelser till belysning av transvestitismens väsen).” Tranås Tidning, October 28, 1933.

“Alfred Charles Kinsey (1894-1956).” American Experience | PBS, January 23, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/kinsey-alfred-charles-kinsey/

Arolsen Archives. “Documents with names from CERVINKAOVA, KARLA.” https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/document/5051002

Arolsen Archives. “Labor reformatory camp Liebenau (Internment Camp Liebenau) / A-C CHARLOTTE CHARLAQUE.” https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/document/1201446

Arolsen Archives. “War Time Card File (Registration cards, employees’ record books, individual correspondence) A-Z /Charlotte Charlaque.” https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/document/71764055

Arolsen Archives. “War Time Card File (Registration cards, employees’ record books, individual correspondence) A-Z /Charlotte Charlaque.” https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/document/71764056

Bauer, Heike. The Hirschfeld archives: violence, death, and modern queer culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017.

Cantu, Benjamin, director. Eldorado: Everything the Nazis Hate. Netflix Studios, 2023.

Charlaque, Charlotte [Charlotte von Curtius] to Christine Jorgenson, February 20, 1953. Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen.

Charlaque, Charlotte to Toni Ebel. October 18, 1946, C Rep 118-10, Nr A 14093, Sheets 39-40, Landesarchiv Berlin.

Charlaque, Charlotte to Toni Ebel. June 24, 1947, C Rep 118-10, Nr A 14093, Sheets 11-17. Landesarchiv Berlin.

Continental Club and Restaurant. “Best International Folk Art (Beste International Kleinkunst).” Advertisement. Aufbau, September 29, 1944.

Curtius, Baroness Carlotta von. “Reflections on the Christine Jorgenson Case.” ONE, The Homosexual Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 3 (March 1955): 27-28.

Dose, Ralf. Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. Translated by Edward H. Willis. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

Ebel, Toni. "Toni Ebel’s Handwritten personal history (Handschriftlicher Lebenslauf Toni Ebel)." C Rep. 118-o1 Nr. A. 14093, Sheet 44. Landesarchiv Berlin.

Feinberg, Leslie. Transgender Warriors: Making History From Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Hartmann, Clara. “Rätsel Um Verbleib Gelöst · Lili-Elbe-Bibliothek.” Lili Elbe Library, September 2, 2024. https://lili-elbe.de/blog/2024/08/dora-richter-trans-raetsel-um-verbleib-geloest/.

Lustbader, Ken. “Charlotte Charlaque Residence.” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, December 2023. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/charlotte-charlaque-residence/

Pace, Eric. “Harry Benjamin Dies at 101; Specialist in Transsexualism.” The New York Times, August 27, 1986, Section D, Page 18.

Portner, Hani. “ACT 3: THE MAGNUS HIRSCHFELD INSTITUTE AND MEMORIAL.” Constellations Archive, 2023. https://constellations-archive.net/archive/imagine-yourself-as-the-mushroom.

Reißner, Joy, Meier-Brix, Orlando (ed.) tin*stories Trans | inter | non-binary history(s) since 1900 ( tin*stories Trans | inter | nicht-binäre Geschichte(n) seit 1900). Münster: edition assemblage, 2022.

Rustin, Richard. “Death Ends Proud Reign of the Promenade’s Queen.” Brooklyn Heights Press, February 14, 1963, 1, 3.

Rustin, Richard. “Charlotte Curtis, Friends Start a Memorial Fit for The Queen.” Brooklyn Heights Press, February 21, 1963, 1.

“Village Art Theater: Theater.” New York Post, December 19, 1942, B.

Wolf, Ari. Conversations with Hani Portner, 2023-2024.

Wolfert, Raimund. Charlotte Charlaque. Trans woman, amateur actress, “Queen of Brooklyn Heights Promenade (Charlotte Charlaque: Transfrau, Laienschauspielerin, “Königin der Brooklyn Heights Promenade”). Leipzig: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2021.

Wolfert, Raimund. “Charlotte Charlaque, Actress (Schauspielerin).” Magnus Hirschfeld e.V, 2023. https://magnus-hirschfeld.de/gedenken/personen/charlaque-charlotte/

Wolfert, Raimund. (Magnus Hirschfeld Society). Conversations with Hani Portner, 2023- 2024.