She'erit ha-Peletah: Women in DP Camps in Germany

Holocaust survivors who gathered in DP (displaced persons) camps were the remnants of a devastated Jewish society which was trying to rebuild itself. They were young single people and 40 percent were women. Family played an important role in their new lives – in the year following liberation, Bergen-Belson saw six to seven weddings a day, and in 1947, the birth rate in DP camps was one of the highest in the world. Young women volunteered to serve as teachers, and 47 percent of students at the first vocational school opened in Landsberg in 1945 were women, who studied sewing and nursing. Women were active in the effort to open immigration to Palestine, establishing a Zionist organization affiliated with WIZO in May 1946. Women also played an active role in presenting and recording survivor testimonies.

Within the field of historiographic research, the concept she’erit ha-pletah (or surviving remnant) is understood in various ways. “Maximalists” apply the term to the Jewish people as a whole, which survived the Nazi attempt to exterminate it as a nation, while “minimalists” hold that it should be applied only to direct survivors of the Nazi regime. For purposes of this article, the term is used solely with reference to those survivors gathered into the DP (displaced persons) camps in Germany, Austria, Italy and France. The greatest concentration of displaced persons was in Germany, hence the focus of the present article.

Displaced Persons Camp: 1945-1957

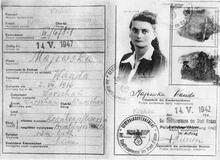

By September 1945, the Allied occupation forces had repatriated more than five million people, including Jewish survivors of the Nazi genocide who returned to the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Hungary, Lithuania and Poland in search of surviving family members. Those Jewish survivors who refused to return to their countries of origin were not recognized as a separate national group but were concentrated in assembly centers according to their national affiliation and given the legal status of “displaced persons.” Responsibility for them was placed in the hands of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) until a solution to their predicament could be found.

Over the course of 1946 and 1947, the number of non-Jewish citizens in the assembly centers gradually declined, while the number of Jewish displaced persons climbed as a result of the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe who made their way to the DP camps in Germany with the aid of Berihah (illegal organization that smuggled survivors to pre-State Palestine). In the autumn of 1945 came the partisans and those who had fought in the forests. They were followed in 1946 by those Polish Jews who had spent the war years in the Soviet Union and returned to Poland under the repatriation agreement only to be driven out again by the fierce antisemitism. In 1947, they were joined by Jews from Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The stream of refugees brought entire families to the DP camps. Despite the great differences between the countries of origin of the survivors, the character of the Jewish society that coalesced in the DP camps was that of Eastern Europe. For all of the internees, the DP camps served as a “way station” until the acceptance of their demand for unrestricted immigration to Palestine and other countries overseas.

The population of displaced persons shifted constantly, making it difficult to estimate its exact numbers. In early 1946, there were close to seventy thousand Jewish displaced persons in Germany in the three Allied occupation zones, including Berlin, twelve thousand in Austria, and ten thousand in Italy. By the end of that year, the number of displaced persons had swelled to 230,000, with 180,000 of them in Germany alone. With the arrival of Jews from Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania, the number of displaced persons in Germany alone rose to 190,000 out of a total of 250,000 in Germany, Austria and Italy.

The bulk of Jews were concentrated in the American-occupied zone in Germany because of the “open-door policy” of the American authorities, in contrast to the British, who imposed harsh entry restrictions in the areas under their control. The refusal of the British to permit unrestricted aliyah to Palestine and the immigration restrictions imposed by the Western states prolonged the internees’ stay in the DP camps until mid–1948.

It was only when the state of Israel was declared on May 14, 1948 and immigration restrictions to the United States and Canada were eased that the mass exodus began. Between July 1948 and June 1949, 53,388 individuals emigrated from Germany to Israel, with another 17,683 coming from Austria. During this same period, 15,322 Jewish DPs emigrated to the United States, 6,009 to Canada, 2,287 to Australia and 10,325 to other countries.

Despite this huge exodus, the DP camps continued to exist. Between 1949 and 1951, there arrived in Germany a new wave of Jewish refugees who were quick to leave the East European states following the institution of Communist regimes. In late 1951, some 19,000 Jews were left in Germany, most of them joining the Jewish communities that reconstituted themselves there. The so-called “hard core,” who refused offers to emigrate to the United States or other Western countries, were concentrated in the Föhrenwald camp, where they remained until 1957.

Gender & Historiography

By September 1945, the Allied occupation forces had repatriated more than five million people, including Jewish survivors of the Nazi genocide who returned to the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Hungary, Lithuania and Poland in search of surviving family members. Those Jewish survivors who refused to return to their countries of origin were not recognized as a separate national group but were concentrated in assembly centers according to their national affiliation and given the legal status of “displaced persons.” Responsibility for them was placed in the hands of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) until a solution to their predicament could be found.

Over the course of 1946 and 1947, the number of non-Jewish citizens in the assembly centers gradually declined, while the number of Jewish displaced persons climbed as a result of the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe who made their way to the DP camps in Germany with the aid of Berihah (illegal organization that smuggled survivors to pre-State Palestine). In the autumn of 1945 came the partisans and those who had fought in the forests. They were followed in 1946 by those Polish Jews who had spent the war years in the Soviet Union and returned to Poland under the repatriation agreement only to be driven out again by the fierce antisemitism. In 1947, they were joined by Jews from Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The stream of refugees brought entire families to the DP camps. Despite the great differences between the countries of origin of the survivors, the character of the Jewish society that coalesced in the DP camps was that of Eastern Europe. For all of the internees, the DP camps served as a “way station” until the acceptance of their demand for unrestricted immigration to Palestine and other countries overseas.

The population of displaced persons shifted constantly, making it difficult to estimate its exact numbers. In early 1946, there were close to seventy thousand Jewish displaced persons in Germany in the three Allied occupation zones, including Berlin, twelve thousand in Austria, and ten thousand in Italy. By the end of that year, the number of displaced persons had swelled to 230,000, with 180,000 of them in Germany alone. With the arrival of Jews from Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Romania, the number of displaced persons in Germany alone rose to 190,000 out of a total of 250,000 in Germany, Austria and Italy.

The bulk of Jews were concentrated in the American-occupied zone in Germany because of the “open-door policy” of the American authorities, in contrast to the British, who imposed harsh entry restrictions in the areas under their control. The refusal of the British to permit unrestricted aliyah to Palestine and the immigration restrictions imposed by the Western states prolonged the internees’ stay in the DP camps until mid–1948.

It was only when the state of Israel was declared on May 14, 1948 and immigration restrictions to the United States and Canada were eased that the mass exodus began. Between July 1948 and June 1949, 53,388 individuals emigrated from Germany to Israel, with another 17,683 coming from Austria. During this same period, 15,322 Jewish DPs emigrated to the United States, 6,009 to Canada, 2,287 to Australia and 10,

The DP camps in Germany and Austria were the subject of extensive research during the last two decades of the twentieth century. Most of the attention was focused on the political aspects of life for the displaced persons: the groups they formed, their struggle for national rights, and the relations they developed with the occupying forces, international and Jewish aid organizations and emissaries from pre-State Palestine. The studies later expanded their scope to embrace the fields of education, culture and religion as these evolved during the enforced waiting period in the camps.

By contrast, the study of women among the She’erit ha-Pletah is still in the early stages and must contend with the fact that contemporary historical sources devoted scant attention to the gender aspects of post-war healing and restoration. The present article seeks to answer the question of whether there was a difference between the rehabilitation of the women as compared to the men, and if so, what was the nature of that difference.

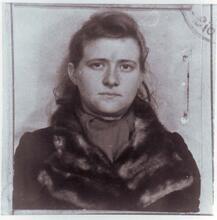

The Nazis’ extermination policy produced a society of survivors that lacked both small children and old people. Women constituted forty percent of this group; their low numbers can be explained by the fact that they had less physical stamina; in addition to this, as mothers of children, they were often automatically sent to the death camps. In general, the survivors were young people without families between the ages of twenty-one and forty-five.

The enormity of the social and emotional devastation of the concentration camp survivors was so great that not even the joy of liberation could temper it. Reports by the liberating forces and the testimony of survivors reveal passivity, apathy, a profound sense of alienation, estrangement, hostility, social anxiety, unhappiness and a burden of loneliness accompanied by fear of the future. Many suffered from impaired memory, inability to concentrate, restlessness, fits of rage, weeping for no apparent reason as a result of emotional anxiety, hypersensitivity and a low response threshold. Upon liberation, the women, like the men, suffered from severe infectious diseases and from tuberculosis.

325 to other countries.

Despite this huge exodus, the DP camps continued to exist. Between 1949 and 1951, there arrived in Germany a new wave of Jewish refugees who were quick to leave the East European states following the institution of Communist regimes. In late 1951, some 19,000 Jews were left in Germany, most of them joining the Jewish communities that reconstituted themselves there. The so-called “hard core,” who refused offers to emigrate to the United States or other Western countries, were concentrated in the Föhrenwald camp, where they remained until 1957.

Marriage and Birth

With the restoration of the family unit starting in the summer of 1945, there slowly began to emerge signs of a social transformation in the lives of the survivors. Data from the camp at Bergen-Belsen indicate that during 1946, 1,070 marriages took place in this camp alone; the first year following liberation saw six to seven weddings a day, and sometimes even fifty in one week.

The need for warmth and intimacy was so great that people often totally ignored the usual criteria for choosing a marriage partner. In many cases, young women married men who were considerably older. Psychologists later claimed that these were “marriages born of desperation.” By deciding to marry, the survivors asserted their sense of obligation to the past, their desire to continue the family line and their commitment to Jewish tradition. The rabbis in the DP camps encouraged women to conduct their family life in accordance with Jewish tradition, thereby perpetuating the memory of their family members lost in the Holocaust.

The women devoted the bulk of their energy to bearing children and raising families. The fear that their fertility had been impaired pushed many women to become pregnant even before they had healed from the ongoing damage of privation and disease. Pregnancies and births took place in the DP camps in such unprecedented numbers that researchers have referred to the phenomenon as a “baby boom.” There are those who see the high birth rate as a form of revenge against the death and destruction caused by the war.

Data from the American-occupied zone in Germany indicate a striking rise in the population of infants and children under five during 1946. In January 1946, there were 120 children under the age of five; by September of that year, the number had reached 4,430. According to a report by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (known as the Joint) in late November 1946, out of 134,541 Jewish displaced persons in the American zone, 3.2 percent were infants of up to one year, 3.5 percent were children aged between one and five, and 10.5 percent were children from the ages of six to fifteen. In 1947, the birth rate in the DP camps reached 50.2 per thousand, one of the highest in the world, dropping to 31.1 by the summer of 1949.

The high birth rate can also be attributed to the arrival of young women who had spent the war years in the Soviet Union and whose state of health was therefore much better than that of the other survivors. In later interviews, the women spoke of their ignorance regarding pregnancy and childbirth, despite the efforts of doctors, UNRRA workers and the Joint to conduct informational programs among the young mothers.

Living Conditions

Conditions in the camps—including lack of privacy, overcrowding and constant dependence on aid organizations—made it difficult to raise children and did little to foster a healthy family life. People were crowded together in huge warehouses, with only blankets to serve as a makeshift “barrier” between families. Several of the camps had no running water. The severe shortage of showers and toilets made it difficult to maintain personal and communal hygiene. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees from Eastern Europe only exacerbated the overcrowding, making it even more difficult to uphold standards of cleanliness and maintain a proper nutritional regimen.

The meager and monotonous diet was provided by a central kitchen, on the basis of ration coupons. While the women and children received a variety of foods from the Joint, their diet was noticeably lacking in dairy products and fresh produce. The only way to obtain these was through bartering with the local population on the black market, which provoked even greater antagonism on the part of the locals towards the DP camp inmates.

The waiting in the camps was made more difficult by the enforced idleness and inactivity. The fact that the Jewish labor force had been worked literally to death during the war led to a hostile attitude toward work on the part of the survivors; moreover, many camp inmates refused in principle to take part in the restoration of the German economy.

The camps themselves offered extremely limited opportunities for employment, among them administrative tasks, clerical work, distributing food and clothing, keeping the camps clean and orderly and maintaining some sort of educational framework.

Education

Education in the DP camps was largely the province of the female inmates. Camp society included few intellectuals, a result of the Nazis’ deliberate policy of wiping out the Jewish intelligentsia. Only a small number of survivors had managed to acquire pedagogical training before the war, and it was they who laid the foundations of the educational network in the DP camps. The combination of the youth of the survivors and the fact that they had been cut off for so long from any educational institution meant that most of the internees, both male and female, had received only an elementary-school education; and there were many young people aged fifteen to eighteen who had not even completed primary school.

The young women who volunteered to serve as teachers had managed to complete high school and sometimes even pedagogical training. With the influx of refugees from Eastern Europe, the pool of young women engaged in education expanded to include teachers who had taken part in the rehabilitation of the educational system in post-war Lithuania. The outstanding figure in the field of education was Dr. Helena Wrubel-Kagan, who established a Hebrew gymnasium (secondary school) in Bergen-Belsen with the aid of soldiers from the Jewish Brigade. At its height, the educational network boasted more than eight hundred teachers in the American zone alone. Precise figures regarding the total number of women teachers in the DP camps are not available, but the information on individual schools indicates that there were schools where half the teaching staff consisted of women and even some where women served as principals.

Women’s involvement in education extended to the haredi (ultra-Orthodox) school system as well. Rivka Horowitz, Rivka Englard, and Rachel Schentzer had been teachers in the Bais Ya’akov haredi educational network for girls, founded in Poland between the world wars by Sarah Schenirer. The three managed to stay alive together throughout the war; in memory of their teacher, Sarah Schenirer, they founded a Bais Ya’akov network in Germany.

Pioneer Movements & Vocational Training

Young women also worked as caregivers and group leaders in “children’s houses” organized earlier by the pioneer movements in Poland and Hungary as an educational framework for orphaned children. With the aid of the Berihah organization, some 3,500 of these orphans were smuggled into Palestine. Despite their lack of educational experience, the young women represented a substitute mother figure of sorts for these young children.

Women inmates were also active in the pioneer movement, with which almost ten percent of the camp population was affiliated. For the young men and women, the “A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz aliyah” groups served as a substitute for their extended family who had perished in the Holocaust. A number of the aliyah A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim aliyah relocated to farmland expropriated from the Germans by the Allied occupying forces and prepared themselves for communal life and working the land in pre-State Palestine. Figures regarding would-be immigrants deported to Cyprus indicate that the aliyah kibbutzim suffered from a constant shortage of women.

To combat the enforced idleness, the camp leadership encouraged the young people to use their free time to learn a profession. In December 1945, the survivors established the first vocational school in the DP camps, at the camp in Landsberg, Germany; almost half (47 percent) of its students were women, most of whom studied to be seamstresses. The groundwork for women’s vocational training was laid by Helena Wolkowitz (b. 1915), who had acquired training and experience in the teaching of fine dressmaking. The constant shortage of clothing for women and children alike created a steady demand for seamstresses within the camps; moreover, sewing was perceived as helpful to the women’s future integration in Palestine or the Western countries. Many of the women also sought training as dental technicians, cosmeticians, translators or secretaries.

In 1948, the vocational training network in the American zone reached its peak, with 8,412 individuals studying at sixty schools throughout the area; 440 courses were offered in thirty-one different occupations. That year, there was a considerable rise in the number of female students taking various sewing courses in the vocational training schools, on the assumption that these skills would prove valuable in their new country.

In addition to dressmaking, women studied nursing. With the arrival of the refugees from Eastern Europe came nurses who had already acquired professional experience in the Soviet Union. From a total of 124 nurses in early 1946, the number had risen to 388 by the start of 1947.

The rise in the number of inmates in the DP camps led to an ongoing shortage of nurses. In February 1948, a nurses’ union numbering 346 members was established in Munich. Women also found work as dental technicians, among other paramedical fields. Courses in cosmetics were also highly popular: this was a profession that combined touch, softness and aesthetics, which had been denied them during the war years, and it did not require a lengthy training period.

Zionist Activity

On the communal level, the DP camps were characterized by widespread support for the Zionist movement. Women were among the earliest organizers of Zionist groups in the camps. At the second Zionist gathering, which took place in Landsberg on August 20, 1945, five women took part out of a total of forty-three representatives from the various camps. But women were quickly relegated to the sidelines; they were not represented on the central committees of the various occupied zones, the leadership bodies of the camps or even at the congresses of the She’erit ha-Pletah. Community work was one of the few activities that brought with it a rise in social status, access to better nutrition and a source of interest to break the monotony of camp life. For the most part, however, the political sphere attracted educated older men with natural leadership abilities, past experience in communal activity and fluency in several languages.

The membership of Dr. Hadassah Bimko Rosensaft on the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone was the exception that proved the rule. In academic research, the rarity of women’s participation in the public sphere has been attributed to the traditional taboo against women’s involvement in political activity and the fact that women were occupied with bearing and raising children under difficult conditions, leaving them little free time for communal work.

In the DP camps in Germany, a Zionist political framework known as the Unified Zionist Organization was established with the aid of soldiers of the Jewish Brigade. It was a central tenet of this group that, in the wake of the Holocaust, there was no longer room for sectarianism in the Zionist camp and that it was necessary to unite all forces in the struggle for aliyah and the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Over the course of 1946, however, political divisions among the camp inmates intensified, with various groups gradually seceding from the Unified Zionist Organization to set up independent party frameworks.

To encourage Zionist activity among the women inmates, the Unified Zionist Organization set up a Zionist women’s group in the Landsberg camp in mid-May 1946. Its major emphasis was on cultural and ideological activities, while the concrete needs of the inmates were considered to be of secondary importance. The program included cultural activities; the study of Hebrew, Zionist history and Jewish history; literary and music evenings; instruction in the care of infants; lectures on disease prevention and other medical topics; fitness activities; and courses in home economics. The Zionist women’s group placed the training of women for aliyah at the head of their priorities.

WIZO Chapters

A different pattern of Zionist activity was reflected in the decision of the women to establish their own Zionist organization affiliated with WIZO. This initiative was more typical of older women who had already been active in WIZO before the war. The pioneer in this effort was Chana Holtzman, a survivor of Bergen-Belsen and former member of the Warsaw chapter of WIZO. With the aid of Jewish army chaplains, she managed to make contact by mail with the WIZO head office in London, requesting their assistance in restarting WIZO activities among the survivors. Holtzman regarded this activity on German soil—soaked as it was with Jewish blood—as a symbol of the national revival and the ultimate proof that the Jewish people could not be destroyed.

For close to a year, a correspondence took place between the camp inmates and the WIZO leadership in London and Palestine. In May 1946, a chapter of WIZO was established in the Belsen camp (in the British zone) with the help of Rivka Weber, a member of the delegation from Palestine who belonged to Young WIZO. The group saw its mission as calling on women to break free of the passivity of the camps and prepare themselves for life in Palestine.

With the arrival from Poland of Malka Kelrich and Gisella Finel, WIZO chapters were also set up in the American zone in Germany during the summer of 1946. These women sought to give WIZO the image of an apolitical organization whose primary goal was “caring for mother and child, and all things pertaining to the Jewish woman, her people and her land.”

The 22nd Zionist Congress in Basel provided a boost for WIZO’s work in Germany. In its wake, a national conference was organized, representing some four thousand members in eighteen DP camps, at which the organizational structure of the new WIZO branches was determined along with the wording of the group’s platform. The organization’s spheres of activity were defined as follows: social assistance, aid to young mothers in the care of their children, assistance in food distribution to children, cultural activities and work on behalf of the JNF.

It was not long before WIZO activities in the DP camps were affected by the political controversies within the Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv in Palestine. The decision of the women’s organizations in Palestine to send a delegation of activist women to set up a joint body of all women’s organizations in Germany was seen by the WIZO women in Germany as an attempt to dismantle their organization. Only when they were promised that the WIZO organization would not be dissolved did the fury abate.

Camp Press & Survivor’s Testimonies

In the cultural sphere, women participated in drama groups that were set up in the camps. The first of these, Amkha (Your People), was established in the summer of 1945 in the Feldafing camp. The performances played an important role in helping the participants work through their experiences and cope with their grief. In early 1946, a troupe of professional actors made the rounds of the DP camps. Students and graduates of Solomon Mikhoels’s Jewish State Theater in Moscow, they had spent the war years in the Soviet Union, performing at the theater in Tashkent. Israel Becker was the driving force behind the group, which functioned from 1946 to 1949. The composition of the troupe changed over the years, with thirteen women performing in the various ensembles.

The press, which was the primary instrument of expression of the survivors, was totally dominated by men and few women sat on the editorial boards of the camp papers. The most important of these, the Landsberger Lager Zeitung,was published in the Landsberg camp; a year later, it changed its name to the Jüdische Zeitung. Rosa Rabinowitz served as director of the paper’s Organization Department; when she died on September 28, 1946, the paper eulogized her with a full-page obituary.

The unique problems of women were not addressed in the camp’s press. It was only in 1948 that the paper began to publish a special section for women, entitled “Winkel Froyen” (Women’s Corner), which dealt with family issues and husband-wife relationships under camp conditions. The section offered practical advice on maintaining good physical health and even published simple recipes. But the women’s voice remained largely unexpressed in the camp papers and it was rare to find articles authored by women. On occasion, poems by women writers were published, such as those of Pessa Mayevska in the Jüdische Zeitung, or Miriam Waksmann, in early issues of the paper Undzer Shtime in Bergen-Belsen. One article by Malka Kelrich, chairwoman of WIZO and the only woman in the writers’ union of the She’erit ha-Pletah, was published in Shriftn, a literary periodical.

One exception was the collecting of survivors’ testimonies, organized by the Central Historical Commission in Munich. Women played an active role in both presenting and recording testimonies. They were members of the aforementioned Commission and of the historical commissions in the various camps and occupied zones. In the three years that it operated, the Historical Commission gathered over 2,500 testimonies, at least a quarter of them given by women. Several of these accounts were published in the historical periodical Fun Letstn Khurbn on the initiative of the Historical Commission. The women’s testimony bears its own unique hallmarks, combining the experiences of the individual witness with those of the collective. The constant separations from family members are a major theme in all of the women’s testimonies; at the same time, the witnesses cite their connection with a sister, brother or friend as a central factor in their survival.

Conclusion

The passivity attributed to the women survivors by the Zionist emissaries seems far from the truth. In fact, the women were active participants in the battle waged by the She’erit ha-Pletah to open the gates of Palestine. In the three years of struggle until the establishment of the state of Israel, the Zionist movement preferred to bring unmarried young men and women to Palestine. On the ship Exodus 1947, which was a symbol of the struggle for free immigration to Palestine, women (including pregnant women) constituted forty-five percent of all adults on board; fifty-six babies were born aboard the ship and on the deportation boats. Women who were taking care of infants and young children remained in the DP camps for a longer period, until the organized migration began in mid-1948.

The surviving remnant that gathered in the DP camps in Germany was a Jewish society in a state of “social moratorium.” Its members had been torn from the framework of their previous lives but had not yet managed to build new ones. In their efforts to begin new lives following the Holocaust, the women of the She’erit ha-Pletah found their own avenues of expression: raising families, bearing children, education, nursing. The women were quick to return to their traditional roles to compensate for their losses on the individual, familial and national levels. Extensive research is still needed to fully comprehend the uniqueness of the rehabilitation process among the women of the DP camps.

Feinstein, Margarete Myers. “Jewish Women Survivors in the Displaced Persons Camps of Occupied Germany: Transmitters of the Past, Caretakers of the Present, and Builders of the Future.” Shofar 24, no. 4 (Summer 2006): 67-89

Giere, Jacqueline D. “Wir sind Unterwegs aber nicht in der Wüste, Erzieung und Kultur in den Jüdischen Displaced Persons-Lagern der Amerikanischen Zone in Nachkriegsdeutschland, 1945–1949.” Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doctors der Philosophie im Fachbereich Erzieungswissenschaften der Wolfgang Goethe Universität zu. Frankfurt am Main, 1992

Grossmann, Atina. “Gendered Perceptions and Self-Perceptions of Memory and Revenge: Jewish DPs in Occupied Post-War Germany as Victims, Villains and Survivors.” In Gender, Place and Memory in the Modern Jewish Experience, edited by Judith Tydor-Baumel and Tova Cohen, 78–107. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2003

Grossmann, Atina, “Mir Zaynen Do: Sex, Work, and the DP Baby Boom.” In Jews, Germans, and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany, 184-235. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Lavsky, Hagit. New Beginnings: Holocaust Survivors in Bergen-Belsen and the British Zone in Germany, 1945–1950. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2002

Mankowitz, Zeev. Life Between Memory and Hope: The Survivors of the Holocaust in Occupied Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002

Myers, Margarete L. “Jewish Displaced Persons Reconstructing Individual and Community in the US Zone of Occupied Germany.” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 42 (1997): 303–322

Schein, Ada. “Educational Systems in the Jewish DP Camps in Germany and Austria (1945–1951)” (Hebrew). Ph.D. dissertation. Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2000

Tydor-Bumel, Judith. “DPs, Mothers and Pioneers: Women in the She’erit Hapletah.” In Double Jeopardy, Gender and the Holocaust, 233–247. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 1998.