Ethiopian Jewish Women

Ethiopian Jewish women have made dramatic changes in their move from Ethiopia to Israel. In different periods in Beta Israel history, women were attributed great power, and reified, as in the case of Queen Judith. Prior to immigration, Beta Israel women in Ethiopian villages were inactive in public and were in charge of the domestic sphere. Immigration to Israel changed Ethiopian Jewish family life radically. In Israel, girls are not allowed to marry at first menstruation and women are encouraged to go out to work. Some young women have become leaders; others have acquired higher education, and are high-profile career women. As the gap between migrant Ethiopian women and men continues to grow, new forms of gender roles and family structure are emerging.

The Ethiopian Jews: Background

The Ethiopian Jews, men and women alike, were known as Falashas in their country of origin, although they have more recently eschewed this appellation with its stigmatic connotation of “stranger,” implying low, outsider status. In Israel, they tend to be called Ethiopian Jews, while in Ethiopia they often referred to themselves—and are referred to in the academic literature—as Beta Israel (Weil, 1997a). The Beta Israel hail from villages in Gondar province, Woggera, the Simien mountains, Walkait, and the Shire region of Tigray. They are divided into two major distinct linguistic entities, one speaking Amharic and the other Tigrinya (Weil 2012a).

The origins of this ethnic minority in Ethiopia are obscure. Almost all researchers, including those who maintain that the Ethiopian Jews did not exist in Ethiopia until the Middle Ages, admit that Jews have lived in Ethiopia from early times (cf. Kaplan 1992). Some say that the Beta Israel are descended from the union of King Solomon and Queen of Sheba; other theories refer to them variously as descendants of Yemenite Jews, Agaus (an Ethiopic indigenous people), Jews who went down to Egypt and wandered south, or even an outgrowth of Jews who inhabited the garrison at Elephantine (Kessler, 1982). Some research suggests that they formed as a group under the influence of Ethiopian Christian monasticism in the fourteenth century (Kaplan 1992; Shelemay, 1986).

In Ethiopia, the Beta Israel practiced a Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah-based, non-Oral-Law style of Judaism. They were monotheistic, celebrated many festivals and fasts prescribed in the Torah, and circumcised their boys on the eighth day. Some religious festivals known to other Jewish communities were not marked by the Beta Israel, but they, in their turn, celebrated certain days not marked by other Jews (Aescoli 1935/6). Their religious practices were heavily influenced by Ethiopic Christians and many elements were common to both religions, such as praying to Jerusalem (Weil 2012b), the common liturgical language of Geez, and the emphasis on Israel and Zion (Pankhurst, 1997). It is significant that the Te’ezaza Sanbat, which some researchers designate as the most ‘authentic’ Beta Israel text, personifies the Sabbath as a woman (Leslau 1951).

The process of the alignment of the Beta Israel with world Jewry had its seeds in the nineteenth century and arguably even earlier, but real contact with world Jewry began only in the twentieth century with Dr. Jacques Faitlovitch (1881–1955), a Semitic scholar from the Sorbonne, who devoted his life to bringing the Jews in Ethiopia into line with other Jews. Dr. Faitlovitch managed to influence sections of the community to adapt to world Jewry (Trevisan Semi, 2007), a process that was completed in the 1980s and 1990s with the transplantation of a whole community to the State of Israel.

Famous Women in Beta Israel History

Interestingly, besides the famous meeting between Queen Sheba and King Solomon, the greatest legend in Beta Israel annals (and those of other peoples and tribes) revolves around a woman, Queen Judith, variously known as Yodit, Gudit (“the bad”), Esther, Esato (=fire), Ga’wa, Tirda Gabaz, or Isat. She has been attributed to the tenth century and the ecclesiastical decline of Axum (the historic capital of the Aksumite Empire in Ethiopia), and she has been identified as a royal Axumite princess and the Queen of foreigners, such as the Bani al-Hamwiyah/Habasha (indigenous tribes in Ethiopia), and the Falashas (Hendrickx 2018; Steyn, 2019). On the one hand, she was portrayed as a beautiful woman of the Ethiopian royal family, much like the Queen of Sheba, and on the other hand, she was portrayed as a despicable prostitute who, at a time of political weakness, killed the Ethiopian king, captured the throne, and as a cruel ruler destroyed Aksum, the capital, persecuted the priests and closed the churches. The identity of Queen Judith/Yodit is not at all clear. The Scottish explorer James Bruce, in his Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, describes how the beautiful queen Judith, queen of the Beta Israel, single-handedly overthrew Christianity and eliminated most of the Solomonic royal dynasty based at Aksum. In its place, she established a Jewish dynasty, which ruled for several generations (Bruce 1790:451–453).

There are distinct similarities and differences between the two great Beta Israel legends mirrored in Ethiopian Christian history, the Queen of Sheba and Queen Judith. Both women were perceived to be forceful royal figures. Both were depicted as converts to Judaism. Both led the Jews against the evil Christians; both were considered to be victorious. However, while according to the Ethiopian text Kebra Negest, the Queen of Sheba established the Solomonic dynasty by having relations with King Solomon against her will, Queen Judith is depicted as the one who destroyed that same lineage.

Beta Israel oral tradition also remembers several outstanding women who occupied high office, both within the community and in society at large. Examples of the former are Rahel, Milat, Abre Warq, and Roman Warq, who were leading members of their community, although dates and exact roles are unknown (Holert 1999).

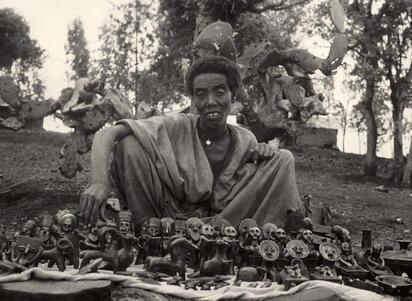

Women's Occupations

Although the Beta Israel reigned supreme in Ethiopia for several generations and succeeded in subjugating their Christian neighbors, by the seventeenth century they had become a powerless minority with little or no rights to land. From the seventeenth century on, the Beta Israel women worked as artists and decorators in Christian churches. By the nineteenth century, the Beta Israel had taken up stigmatized craft occupations (Quirin, 2011). The men became blacksmiths and weavers and the women became potters, a low-status profession associated with fire and danger and with the belief that the Falashas were buda, supernatural beings who disguised themselves as humans during the day and at night became hyenas that could attack humans. “Falasha pottery,” which is still famous in the Wolleka village in the Gondar region, became a major industry and Beta Israel women selling pots and statuettes attracted many tourists, particularly from the 1970s to the 1990s.

The Beta Israel in Ethiopia tended to live in scattered villages located on hilltops near streams. It was the women’s job to haul water to their homes in earthenware jugs strapped to their backs. Women were in charge of the domestic sphere, baking the basic bread (enjera) on an open hearth, which they also stoked to gain warmth. They prepared the stew (wat), commonly made of lentils and chicken or meat, to go with the enjera. The meal was often accompanied by a type of home brew (talla) made of hops, other grains, and water and fermented in containers made by women. Food was stored in baskets made of rushes from local plants, dried in the sun and twisted into coils. Women spent time weaving these brightly colored baskets, which could also be used to serve food, if the basket was flat-topped. Preparation of coffee was also the province of women, who washed and roasted the raw coffee beans before grinding them manually in a mortar. They brewed the coffee in a pot over the fire and served it in small cups to guests, primarily females, who dropped in to drink coffee and exchange gossip.

Women looked after young children. A mother would strap the smallest baby on her back, while drawing water from the stream or cooking. Young boys stayed with her in the home until they joined their fathers in the field; young girls were expected to help their mothers and take care of the younger children until the age of marriage, around first menstruation.

Masculinity and Femininity

Among the Beta Israel in Ethiopia, masculinity was an ultimate value. The Amharic language is full of expressions praising men and degrading women. Shillele war songs, also sung at weddings and other ceremonious occasions, are designed to arouse male bravery before battle (Herman 1999). A well-known Amharic proverb says: “It is good to beat donkeys and women.” Men’s sexual organs are, by definition, the source of their masculinity. Female genital surgery or female circumcision (otherwise known as genital mutilation) was normative among Beta Israel women (Grisaru et al. 1997). In Beta Israel society, men had to gain sexual prowess. They were allowed to experiment during the stage of adolescence (goramsa), whereas females had to be virgins at marriage, which usually took place soon after first menstruation. While males were expected to be sexually experienced, Beta Israel females could be excommunicated if they were not virgins at marriage. Although marriage was officially monogamous, in practice Beta Israel men often entered polygamous unions with a second wife, or relations with a common-law wife, a concubine, a slave (barya), or a divorced woman (galamotta) who was searching for “protection” in Ethiopian terms (Weil 1991). A rich man could have several women, usually residing in different villages so that there was little knowledge of the other women or contact between them. Older man could marry a younger bride, thereby proving his status and wealth to the society at large. Whereas masculinity was symbolized by the staff which every Beta Israel male carries in Ethiopia, femininity was symbolized by blood.

The Purity of Women

For the Beta Israel, as for many others, the purity of women and their blood signified womanhood and the pulse of life as it revolved around sexual relations and the renewal of male-female relations.

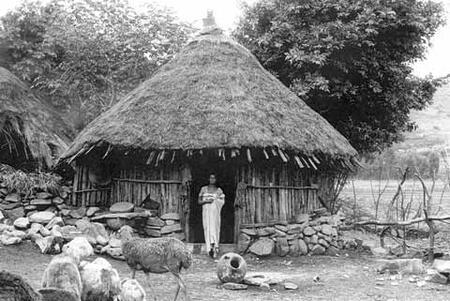

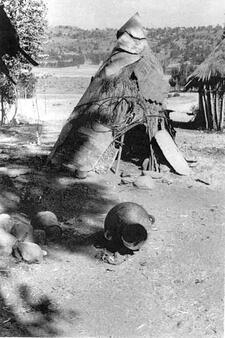

The Bible states: “When a woman conceives and bears a male child, she shall be unclean for seven days, as in the period of her impurity through menstruation…. The woman shall wait for thirty-three days because her blood requires purification; she shall touch nothing that is holy, and shall not enter the sanctuary till her days of purification are completed. If she bears a female child, she shall be unclean for fourteen days as for her menstruation and shall wait for sixty-six days because her blood requires purification” (Leviticus 12:1, 2–6). The Beta Israel of Ethiopia observed this tenet in strict fashion, precisely following the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah commandment, isolating the woman in a hut of childbirth (yara gojos/ ye-margam gogo) for forty days after the birth of a boy and eighty days after the birth of a girl.

In Leviticus, it is further written: “When a woman has a discharge of blood, her impurity shall last for seven days; anyone who touches her shall be unclean till evening. Everything in which she lies or sits during her impurity shall be unclean” (Leviticus 15:19–20). In Ethiopia, every woman belonging to the Beta Israel spent approximately a week in a special menstruating hut (ye-margam gogo/ye-dam gogo/ye-dam bet), where she was prohibited by virtue of her impure blood from coming into contact with people who were in a pure state. She was thus isolated for the length of time of her menstrual period and could share the hut only with other menstruating women. Since her impurity was contaminating, she was not allowed to dine or spend time with pure people, least of all her husband, who could resume sexual relations with her only after she had purified herself in the river. A series of stones surrounded the menstruating hut, separating the impure women from other members of the village. In many villages, the hut was situated almost outside the village, on the peripheries between conquered, civilized space (the village) and the unknown, the wilds, the unconquerable space (the outside). However, in the village of Wolleka near Gondar, the menstruating hut was situated on the hill in the center of the village, far away from the view of passing tourists buying “Falasha pottery” but nevertheless in center-stage as far as the villagers were concerned. It was marked off by stones surrounding the hut in circular fashion, and little children would push food on ceramic plates inside the circle, which would then be taken by the menstruating women. Although Faitlovitch and other Westerners, as well as Ethiopian pupils who had studied in the West, tried to persuade the Beta Israel women not to observe the purity laws according to the Biblical precepts and tried to encourage them to come in line with Jews elsewhere (Trevisan Semi 2007), Beta Israel women in Ethiopia kept these rules strictly until their immigration to Israel, and often thereafter.

Contact with the Western World

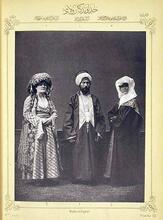

The Beta Israel had little contact with the Western world before the nineteenth century. Protestant missionaries from the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews succeeded in converting some Beta Israel to Christianity. In 1867, Prof. Joseph Halevy (1827-1917), a Semitic scholar from the Sorbonne in Paris, met with the Beta Israel in Ethiopia. In a detailed report in 1877 to the Alliance Israelite Universelle, Halevy described the religious practices of his co-religionists, who had not been exposed to the Oral Law, and recommended steps to improve their socio-economic conditions; no action, however, was taken.

In 1904, Dr. Jacques Faitlovitch (1881-1953), a student of Prof. Joseph Halevy, left Paris under the sponsorship of Baron Edmund de Rothschild for his first expedition to Ethiopia. Between then and 1935, he brought out of Ethiopia 25 young males, whom he “planted” in different Jewish communities in Palestine and Europe (Weil 2010). No female was selected to study in Europe since it was considered too dangerous a voyage, but there were one or two girl pupils at Dr. Faitlovitch’s school in Addis Ababa, founded in 1923.

Migration to Israel

There was no mass emigration from Ethiopia by the Beta Israel after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, as there was with other Jewish communities. In 1952 and 1956, Emperor Haile Selassie allowed two groups of young Beta Israel pupils to study in a dormitory school, Kfar Batya, in Israel, on the condition that they return. A few of the pupils were female and two women stayed on in Israel after marrying Israeli men.

In 1973, on the basis of the halakhic precedent by David ben Solomon ibn Zimr, (1479-1573), also known as the Radbaz, that the “Falasha” (sic) are members of the lost tribe of Dan, Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel Ovadiah Yosef declared that they could be accepted as lost Israelites and thereby return to their historic homeland. In 1975, the Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren also accepted the Ethiopian Jews into the fold.

In 1984–1985, 7,700 Ethiopian Jews were airlifted from the Sudan to Israel in Operation Moses, and in 1991 14,400 were airlifted in 24 hours from Addis Ababa to Israel in Operation Solomon. Some women gave birth on the flight itself. During the 1990s, thousands of people belonging to the group today called the Feresmura or Felesmura (Jews who had converted to Christianity from the nineteenth century on) migrated to Israel. At the end of 2017, the population of Ethiopian origin in Israel numbered 148,700 residents. Approximately 87,000 were born in Ethiopia, and 61,700 were Israeli-born with fathers born in Ethiopia.

Changes in Family Life

One of the greatest changes the Ethiopian Jewish community has undergone in Israel in their move from an underdeveloped society to a modern, Western society is in the realm of family and personal relations. Female genital surgery is hardly ever performed in Israel and women express no desire to continue this practice (Grisaru et al. 1997); today it has died out. Girls can no longer marry at first puberty; it is illegal to marry in Israel before the age of seventeen. In addition, girls have to attend school until the minimum age of sixteen. According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (2018), Ethiopian Jews in practice marry at a later age than the overall Jewish population, although it is possible the state is unaware of earlier marriages. Endogamy is the norm; 88% of individuals (92% of men and 85% of women) of Ethiopian origin marry partners from their community.

Married women are encouraged by social workers and others to go out to work in order to assist with the family income, and it is often easier for women to find employment than men, particularly in the temporary, unskilled jobs in which Ethiopian Jews tend to congregate, despite the numerous vocational courses offered to the community. Rural Beta Israel handle money and manage bank accounts for the first time; a woman’s salary may be paid straight into her bank account, or she may be earning more than her husband. Quarrels often break out between spouses over genzeb (Amharic: money). The Israel rabbinate has established a special department dealing with Ethiopian divorces. The divorce rate among Ethiopian Jews in Israel today is more than double the rate among the overall Jewish population (19 out of every 1,000 marriages, compared with 9 per 1,000 marriages among the overall Jewish population) (Central Bureau of Statistics 2018). One-third of all Ethiopian Jewish families in Israel are one-parent families; the other two-thirds are largely made up of “complex families” constructed from two or more one-parent families, which are intrinsically unstable (Weil, 1991). The main reason for this is the demasculinization experienced by Ethiopian Jewish men. Males no longer reign supreme; “Israeli” women answer back. If women are beaten, as was the practice in Ethiopia, they can turn to the police and file complaints against their husbands.

Between 1995 and 2007, the number of femicides (wife-murders) among Ethiopian immigrants in Israel was 21 times higher than among non-Ethiopian Israels (Sela-Shayovitz 2010). Between 2005 and 2008, 28.9% of the intimate partner murders in Israel were perpetrated by Ethiopian males, despite the fact that Ethiopian Jews make up only 1.6% of the Israeli population. There was not a single case of an Ethiopian woman in Israel murdering a man (Weil 2014). A small sample of Ethiopian women survivors of femicide attacks all related similar stories. They were born in small Ethiopian rural villages; they were forced to marry their husbands or were abducted by them; they suffered severe domestic violence, both in Ethiopia and after their emigration, of which social workers and kin in Israel appeared to be unaware. In all cases, the husband suspected that his wife was unfaithful to him and attempted to kill her in the domestic arena with a knife, in the apartment in which their children were present.

Today, the rate of femicide among the Ethiopian population in Israel is declining. The vast majority of young women in Israel of Ethiopian origin, whether married or divorced, model themselves on their Israeli female counterparts and pay at least lip-service to gender equality, even in the domestic arena.

Changes in Education

Since their immigration to Israel, both males and females attend school. Whereas between 1987 and 1989, nearly ten percent of girls of Ethiopian origin of high-school age were not studying at any educational institution, probably because they were already mothers (Weil 1997b), today nearly every female adolescent is enrolled in school. However, some young Ethiopian female adolescents, like male youth, drop out of school, albeit at a slower rate.

At the other extreme, some women are among the forerunners of those receiving higher education in Israel. There are Ethiopian-Israeli women who hold doctorates; other women have completed their MAs in law, social work, social sciences, or physiotherapy. In the Hebrew University Program for Excellence in Education among Ethiopian Jews, which trained young Ethiopian Jews as teachers, just over half the students were female (Weil 2012c).

Occupations and Status in Israel

According to a 2015 report, 53% of Ethiopian Israelis pass their official high school matriculation examinations, compared to 75% among the general population of Jewish high school students (Fuchs and Gilad 2015). Thirty-six percent of Ethiopian Israelis, who moved to Israel at an older age graduate from high school, compared to 90% in the general Jewish population. Twenty percent of Ethiopian Israelis who were born in Israel or migrated to Israel at a young age hold an academic degree, as compared to 40% of the rest of the Jewish population in Israel.

Among employed Israelis of Ethiopian origin who moved to Israel after the age of 12, about 50% of women work as cleaners. However, for Ethiopian Israelis with an academic degree, rates of labor market integration into occupations that demand highly skilled workers are similar to the general Jewish population. More females gain academic degrees than males, and therefore Ethiopian Jewish women in Israel are in general more successful than their male counterparts. Gaps between female Ethiopian-Israeli students and other Jewish female students still exist, but they are much smaller than the gaps between male students (Fuchs and Wilson 2017). In 2016, two Ethiopian-Israeli women were appointed to be judges: Ednaki Sebhat Haimowitz and Esther Tafta Gardi. Tsega Melaku is a well-known Israeli journalist. Pnina Tamano-Shata is the first Ethiopian woman in Israel to become a Minister in the Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset. Currently, she and another woman of Ethiopian origin, Tsega Melaku, are serving as Members of the Knesset. Meski Shibru-Sivan and Esther Rada are famous Ethiopian Jewish actresses and singers. Hadas Maladi-Mitzri was the first lieutenant in the IDF (Israel Defense Forces). Titi Aynaw won the Miss Israel prize in 2013. Tahounia Rubel is one of several famous Israeli models.

While Ethiopian Jews in Israel are afforded equal privileges and responsibilities in practically every sphere of life (Weil 1999), they still experience deprivation and racism. In the 2019 riots in the wake of the shooting of an Ethiopian Jewish youth Solomon Teka by an Israeli policeman, young girls took an active part in the demonstrations.

Conclusion

Ethiopian Jewish women have made dramatic changes in their move from Ethiopia to Israel. In different periods in Beta Israel history, women were attributed great power, and sometimes reified, as in the case of Queen Judith. In other periods, and particularly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries prior to immigration, Beta Israel women were inactive in public and were in charge of the domestic sphere. In Ethiopian villages, women looked after the young children, drew water from the stream, and cooked for them and their menfolk. Some women were educated, but since the age of marriage was so low, very few finished school. Women’s purity was central to both women and men, and women were isolated in a special hut during menstruation and after childbirth.

Immigration to Israel changed Ethiopian Jewish family life radically. In Israel, girls are not allowed to marry at first menstruation and women are encouraged to go out to work. Some young women have been referred to welfare institutions; some live beneath the poverty line. One third of Ethiopian families in Israel are one-parent families. At the same time, some young women have become community leaders; others have acquired higher education and are high-profile career women. As the apparent gap between immigrant Ethiopian women and men continues to grow, and as the Aliyah of more and more Ethiopians take place, new forms of family structure and adjustments are emerging.

Aescoli, A. The Falashas: Bibliography. Vol. 12. Tel Aviv: 1935/6,

Bruce, James. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile. London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1790.

Central Bureau of Statistics, 2018: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2018/326/11_18_326e.pdf.

Faitlovitch, Jacques. Notes d’un Voyage Chez les Falachas (juifs d’Abyssinie). Paris: Leroux: 1905.

Fuchs, Hadas and Gilad Brand. Education and Employment Trends Among Ethiopian Israelis. Jerusalem: Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, 2015.

Fuchs, Hadas andTamar Friedman Wilson. Education and Wage Trends Among Ethiopian Israelis — Differences by Gender. Jerusalem: Taub Center, 2017.

Grisaru, Nimrod, Simcha Lezer, and R.H. Belmaker. “Ritual Female Genital Surgery Among Ethiopian Jews.” Archives of Sexual Behaviour 26, no. 2 (1997): 211–215.;

Hendrickx, Benjamin. “The Letter of an Ethiopian King to King George II of Nubia in the framework of the ecclesiastic correspondence between Axum, Nubia and the Coptic Patriarchate in Egypt and of the events of the 10th Century AD.” Pharos Journal of Theology, 2018, Vol. 99 - Online @ http//:www.pharosjot.com, accessed 4 July 2019.

Sergew Hable Sellassie. "The Problem of Gudit." Journal of Ethiopian Studies Vol. 10 No. 1 (January 1972): 113-24.

Herman, Marilyn. “The Beta Israel Band of Porachat Ha Tikva: War in Songs and Songs in War.” In The Beta Israel in Ethiopia and Israel: Studies on the Ethiopian Jews, edited by T. Parfitt and E. Trevisan-Semi, 181–190. Richmond: Curzon, 1999.

Holert, K. “Women in History and Historiography: Research on Women of the Beta Israel.” In The Beta Israel in Ethiopia and Israel: Studies on the Ethiopian Jews, edited by T. Parfitt and E. Trevisan-Semi, 160–168. Richmond: Curzon, 1999.;

Kaplan, Steven. The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Ethiopia. New York: NYU Press, 1992.

Kessler, D. The Falashas: The Forgotten Jews of Ethiopia. London: African Publishing Company, 1982.

Leslau, Wolf. Falasha Anthology.Yale Judaic Series. Vol. 6. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951.

Pankhurst, Richard D. “The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Their Ethiopian Setting.” In Ethiopian Jews in the Limelight. Israel Social Science Research, edited by Shalva Weil, 1–12. Jerusalem: 1997.

Quirin, James The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews: A History of the Beta Israel (Falasha) to 1920. 2nd edition. Hollywood, CA: Tsehai Publishers, 2010.

Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. Music, Ritual and Falasha History. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 1986.

Sela-Shayovitz Revital. “The role of ethnicity and context: intimate femicide rates among social groups in Israeli society.” Violence Against Women vol. 16 (2010): 1424-1436.

Steyn, Raita. “Gudit, a Jewish Queen of Aksum? Some Considerations on the Sources and Modern Scholarship, and the Use of Legends.” Journal for Semitics, 28, 1 (2019). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25159/2663-6573/6003.

Trevisan-Semi, Emanuela. Jacques Faitlovitch and the Jews of Ethiopia. London and Portland, OR: Vallentine Mitchell, 2007.

Weil, Shalva. One-Parent Families among Ethiopian Immigrants in Israel. (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Research Institute for Innovation in Education, The Hebrew University, 1991.

Weil, Shalva. “Collective Rights and Perceived Inequality: The Case of Ethiopian Jews in Israel.” In Divided Europeans: Understanding Ethnicities in Conflict, edited by Tim Allen and John Eade, 127-144. The Hague/London/Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1999,

Weil, Shalva. “Ethiopian Jewish Women: Trends and Transformations in the Context of Trans-National Change. Nashim vol. 8 (2004): 73-86.

Weil, Shalva. “Beta Israel Students Who Studied Abroad 1905-1935.” In Research in Ethiopian Studies: Selected Papers of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Trondheim, July 2007, edited by Harald Aspen et al, 84-92. Wiesbaden, Germany: Harrassowitz, 2009.

Weil, Shalva. "Ethiopian Jews: the Heterogeneity of a Group." In Cultural, Social and Clinical Perspectives on Ethiopian Immigrants in Israel, edited by Nimrod Grisaru and Eliezer Witztum, 1-17. Beersheba: Ben-Gurion University Press: 2012.).

Weil, Shalva. "Longing for Jerusalem Among the Beta Israel of Ethiopia." in African Zion: Studies in Black Judaism, edited by Edith Bruder and Tudor Parfitt, 204-217. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing: 2012.

Weil, Shalva. “I am a teacher and beautiful: the feminization of the teaching profession in the Ethiopian community in Israel.” In Immigrant Women in Israeli Society, edited by Pnina Morag- Talmon and Yael Atzmon, 207-223. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute: 2012.

Weil, Shalva. “The Complexities of Conversion among the ‘Felesmura.’” In Movements in Ethiopia, Ethiopia in Movement: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, edited by Eloi Ficquet, Ahmed Hassen and Thomas Osmond, 434-445. Addis Ababa: French Center for Ethiopian Studies, Institute of Ethiopian Studies of Addis Ababa University; Los Angeles: Tsehai Publishers, 2016.

Weil, Shalva. “Failed Femicides among Migrant Survivors.” Qualitative Sociology Review 12, no.4 (2016): 6-21.