Eve: Midrash and Aggadah

Different rabbinical interpretations of Eve’s creation agree with and dispute the traditional narrative of her formation from Adam’s rib. Regardless, her character is posited to be that of the original and quintessential woman. The Midrash interprets her traits as representative of the negative aspects of femininity, especially because her transgression of being deceived by the serpent and subsequently tempting Adam is constructed as the original sin. Eve’s punishment for this sin is also tied to the traditional ideas of the fundamentals of womanhood – childbirth, pregnancy, and male spousal domination.

Introduction

The Rabbis view Eve, the first woman, as embodying the qualities of all women, and of femininity in general. As God’s handiwork, she is portrayed as the most beautiful woman who ever lived, and there was no fairer creature but her husband Adam. The midrashim about her exude an air of primacy: the first mating between Adam and Eve is described as a magnificent wedding, and their first intercourse aroused the serpent’s jealousy. The primal sin is generally symbolic of man’s sins, and through it the Rabbis seek to clarify why men trespass.

The depiction of the woman’s creation leads the Rabbis to inquire into gender differences and the nature of the female sex, all through the eyes of the male Rabbis. They discuss woman’s different temperament, her mental maturity, her habits, the physical shape of her body, her behavior, and other aspects of female existence. The Rabbis attempt to provide an explanation for gender differences by means of a portrayal of woman’s different creation, and also as being a result of the sin of the Garden of Eden. Eve’s punishment is examined at length in the dicta of the Rabbis, who exhibit a certain degree of empathy in their ability to describe women’s suffering during the first three months of pregnancy, during birth, in instances of miscarriage, the pain of raising children, that of menstrual periods and other afflictions.

The various midrashim reveal diverse male perceptions of women in the time of the Rabbis, some positive and flattering, and others negative. Nonetheless, the Rabbis encourage marital life and depict the man who remains alone as depriving himself of many boons. Thus, some midrashim present the first mating of Adam and Eve as the renewed connection of a creature that was split in two, or as a man who found what he had lost.

The Creation of Eve

In the Talmudic depiction, Adam and Eve’s first day on earth is divided into twelve hours. In the first hour, Adam’s clay is heaped up. In the second, he becomes an inert mass. In the third, his limbs extend. In the fourth, he is infused with a soul. In the fifth, he stands on his feet. In the sixth, he gives names to all of creation. In the seventh, Eve becomes his mate, and in the eighth, “they ascended to the bed as two, and descended as four” (Cain and Abel were born). In the ninth, he was commanded not to eat of the tree, in the tenth, he went astray, in the eleventh, he was judged. And in the twelfth, he was expelled and departed (BT Sanhedrin 38b).

The Rabbis have different opinions about the source from which Eve was created. Gen. 2:21 states that “He took one of his ribs.” One exegetical opinion understands zela (rib) as “side,” as in (Ex. 26:20) “and for the other side wall [zela] of the Tabernacle”; hence, God created Eve from Adam’s sides. In another midrashic understanding, God took a rib from between two others and closed the flesh under the remaining ribs (Gen. Rabbah 17:6). According to these opinions, God removed something from Adam when He created Eve. Comparing Eve’s creation with the construction of the Tabernacle imparts sanctity to her, and the Rabbis frequently draw analogies between the creation of a family and the erection of the hallowed Tabernacle. Yet another opinion is based on the description of Creation in Gen. 5:2 which reads “male and female He created them,” from which it derives that Adam was created androgynous. A similar notion is that Adam was created two-faced, as it is said (Ps. 139:5): “You hedge [or, formed] me before and behind” (this creature had a face in front and another behind, one of a male, and the other of a female). In creating Eve, God cut this creature into two, forming a back for Adam and a back for Eve (Gen. Rabbah 8:1; a similar motif appears in the early Babylonian literature and in Plato’s Symposium; see the references by L. Ginzberg, Legends of the Jews, vol. 5, pp. 88–89, n. 42). According to this A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash, Adam’s creation did not precede that of Eve, and the two were created together, like all the other creatures that were created male and female. The creation of Eve is not presented as an act of detracting from and harming another complete creature, but as an act of separation, just as the creation of the upper and lower waters and of light and darkness were acts of detachment between two elements that had previously existed in an admixture. The existence of both genders in a single body vividly expresses the notion that the mating between the two sexes reconstructs the original perfection that existed during the time of the Creation, thus enabling us to understand those dicta in praise of marriage which assert that man is incomplete without a wife (Gen. Rabbah 17:2).

A completely different approach is expressed in the midrash that observes that the letter samekh does not appear from the beginning of Genesis until the creation of Eve, until Gen. 2:21, which states: “and closed up [va-yisgor] the flesh at that spot.” This teaches that when Eve was created, Satan was created with her (as is alluded by the letter samekh or sin). The Rabbis object, noting that the letter samekh appears in the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah before this, in Gen. 2:11, 13: “the one that winds through [ha-sovev]”; the answer given is that verses 11 and 13 speak of the creation of the rivers, and not that of the human race (Gen. Rabbah 17:6). This approach depicts the creation of Eve negatively; she represents man’s evil urge, and she will cause him to sin. The appearance of the letter samekh before this verse merely emphasizes the negative tendentiousness of this teaching.

Another midrash relates that Eve’s creation occurred while Adam was sleeping, and he neither knew nor even sensed anything when God created her from his rib. With this in mind, a noblewoman asked R. Yose: “But why stealthily?” [That is, why did God take Adam’s rib without his knowledge, after causing slumber to fall upon him?] He replied: “If a person entrusted you with a single uncia [a small weight] of silver clandestinely, and returned to you a libra [= 12 unciae] of silver in public, is this theft?” She asked further: “And why in secrecy?” [Why did He create her while Adam was sleeping, and not while he was awake, so that he could see her at the moment of her creation?] He answered her: “Initially, He created Eve when she was full of secretions and blood, and he [Adam] cast her away from him. He created Eve a second time” [and therefore He let him sleep, so that he would not see her as she was created] (Gen. Rabbah 17:7). This midrash places the questions in the mouth of a Gentile woman of noble station who takes an interest in Judaism. Underlying her questions is the feeling that there is something unworthy in the manner of Eve’s creation, which is conducted stealthily and in secret, while Adam sleeps, without his knowledge or consent.

According to R. Yose, God did indeed take Adam’s rib surreptitiously, but he received manifold benefit when God gave him Eve. In this midrashic retelling, the woman was created from a body part of small worth, but God improved her many times over when she was returned to Adam. This positive depiction of the woman is accompanied by the conception of the woman as man’s possession. In the second part of the exegetical discussion, the woman is set forth as one who is meant to find favor in man’s eyes, as an instrument of beauty, and therefore he is spared the process of creation. The second answer also alludes to the creation of two Eves (see below: “Two Eves”).

Another midrash is occupied with the physical appearance of the woman’s body, which differs from that of the man. Gen. 2:22 states: “And the Lord fashioned the rib,” from which the Rabbis learned that God fashioned Eve as a storehouse [for fruits]. Just as a storehouse is narrow at the top and broad at the bottom to hold the fruits, so, too, the woman is narrow above and broad below so that she can bear the fetus (BT Berakhot 61a). Eve’s body structure is here presented as functional, for purposes of pregnancy. This dictum explains the different physical structure of man and woman as part of God’s wisdom in Creation, in which each body serves the need of its gender.

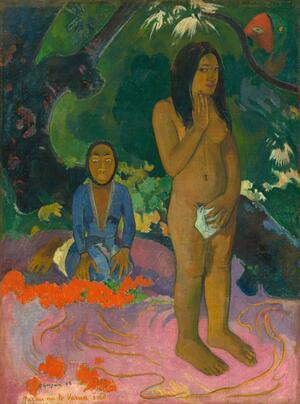

Eve’s Beauty

In the midrashic account, Eve was created whole (with all her limbs fully developed), as was Adam; according to one view, they were created as twenty year olds (Gen. Rabbah 14:7).

The Rabbis maintain that Eve was the most beautiful woman ever. To illustrate this, they say that all humans resemble apes (i.e., are ugly) in comparison with Sarah’s beauty, while Sarah, in turn, looked like an ape in comparison with Eve. Only Adam was handsomer than she, beside whom she, in turn, looked like an ape (BT Bava Batra 58a). This midrash has Adam being the most beautiful creature in all the world, since he was created in God’s image, and directly by Him. Eve, also, was God’s handiwork, and therefore no woman was as beautiful as she, even though she was lesser than Adam, for she was a secondary creation, from Adam’s body.

Eve and the Feminine Nature

For the Rabbis, the differing creation of Adam and Eve explains the divergent natures of men and women. Explanations in this vein appear in a series of questions put to R. Joshua. People asked him about woman’s nature, which differs from man’s character, and R. Joshua explained to them that such phenomena are connected with the manner of woman’s creation. R. Joshua was asked: “Why does the woman use perfume, while the man does not?” He replied: “Adam was created from the earth, which never stinks, while Eve was created from a bone; if flesh is left for three days without salt, it will immediately stink” [and so women use perfume, to conceal the stench of flesh]. They continued to ask: “Why is a woman’s voice clearer and higher than a man’s?” He told them: “If you fill a bowl with meat [and strike it], the sound will be low and thick; but if you place a bone in it, the sound will be clear and high” [thus man’s body, which is filled with earth, while the woman was created from a bone, and therefore her voice is clear]. They then asked: “Why is a man easily mollified, but not a woman?” He explained: “Adam was created from the earth, and if you put a drop of water on it, it immediately absorbs it. Eve was created from a bone; and if you soak a bone in water, even for several days, it will not absorb the water” [consequently, a woman is difficult to appease]. They asked: “Why does a man ask a woman [to marry and engage in intercourse], but a woman does not ask a man?” He replied: “To what is this comparable? To a person who lost something. He seeks what he has lost, but what he has lost does not seek him” [Eve was part of Adam’s body, and therefore he must restore the part that he lacks]. And yet another question: “Why does the man put seed in the woman, but the woman does not put seed in the man?” His reply: “This is like a person who has a deposit in his hand, and he seeks a trustworthy person with whom to entrust it” [and the woman may be trusted to guard the deposit] (Gen. Rabbah 17:8). Some of the female traits mentioned in this midrash are positive, such as the woman’s inclination to perfume herself, her clear voice, and her trustworthiness. R. Joshua explains to his questioners that woman’s nature differs from that of man from their inception; gender differences are imprinted in their disparate fashioning, and women are to be accepted as they are.

Another midrash uses the creation of Eve to cast light on negative traits that it identifies with the female nature. The Rabbis derived the word va-yiven in “And the Lord fashioned [va-yiven] the rib” (Gen. 2:22) from the word hitbonenut: God hitbonen (looked and thought) from which part of the man’s body the woman should be created. He said: I will not create her from the head, so that she will not raise up her head [i.e., be haughty]; not from the eye, so that she will not be curious [desiring to see everything]; not from the ear, so that she will not be an eavesdropper; not from the mouth, so that she will not be talkative; not from the heart, so that she will not be jealous; not from the hand, so that she will not be touching everything; not from the foot, so that she will not be a runabout [going out to the marketplace]; but from the rib, which is a concealed place within man: even when man stands naked, it is concealed. For every part of her that He created He said to her: “Modest woman, modest woman.” Notwithstanding all this, God said (Prov. 1:25): “You spurned all my advice”—I did not create her from the head, but she nevertheless raises up her head, as it is said (Isa. 3:16): “And walk with heads thrown back”; and not from the eye, but she nevertheless is curious, as it is said (ibid.): “with roving eyes”; not from the ear, but she nevertheless is an eavesdropper, as it is said (Gen. 18:10): “And Sarah was listening at the entrance of the tent”; not from the heart, but she nevertheless is jealous (Gen. 30:1): “Rachel became envious”; not from the hand, but she nevertheless touches everything, as it is said (Gen. 31:19): “and Rachel stole her father’s household idols”; and not from the foot, but she nevertheless goes out to the marketplace (Gen. 34:1): “Now Dinah went out” (Gen. Rabbah 18:2).

An opposite approach is exhibited by another exegesis of “And the Lord fashioned [va-yiven] the rib,” that understands va-yiven as coming from the word binah, wisdom. When God created Eve, He gave the woman more wisdom than to the man. Thus, the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah prescribes (Mishnah Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.Niddah 5:6):

The vows of a girl eleven years and one day of age must be examined; if she is twelve years and a day of age, her vows are valid, but they must be examined throughout the twelfth year. The vows of a boy twelve years and one day of age must be examined; if he is thirteen years and one day of age, his vows are valid, but they must be examined throughout the thirteenth year.

(This mishnah teaches that the woman precedes the man by an entire year in her understanding of the significance of her vow.) One opinion, however, reverses the order of the mishnah, and has the boy precede the girl by a year, since the man usually goes forth to the marketplace and gains wisdom from people, while the woman customarily stays at home (Gen. Rabbah 18:1). Apparently, some authority was not enamored of the assertion that the woman has more wisdom than the man. The reason given here, that the man is more exposed to what happens in the world because he goes out to the marketplace, actually supplements the above mishnah: despite her remaining within her house, and her not going forth to the marketplace, she nevertheless is gifted with greater wisdom than the man.

All the dicta in this section identify gender differences: in temperament, in human nature, in physical structure, and in intellectual configuration. Such teachings, by their very nature, are generalizations. Since these texts were written by men, they reveal to the contemporary reader how the men of the time of the Rabbis perceived feminine nature and how they defined gender differences. We learn from these dicta of men’s suspicion of those women who go out to the marketplace unsupervised: going about in public is presented as improper and dangerous.

Two Eves

The midrash relates that God initially created Eve full of secretions and blood, and when Adam saw her, he cast her away from him because she repelled him. God then created Eve a second time, thus causing Adam to exclaim (Gen. 2:23): “This one at last is bone of my bones” [now, the second time, she is from my bones, and not from secretions and blood] (Gen. Rabbah 18:4). Eve’s first creation is presented as being like the birth of a fetus, which emerges from its mother’s womb full of secretions and blood. This was God’s first thought, so that there should be a model for all future births. But God also understood the need for Eve to find favor with Adam, to ensure mankind’s continued existence. He therefore created her again, this time as attractive and desirable. Adam’s reaction presents the woman’s role as a beautiful vessel that will find favor in her husband’s eyes.

The Rabbis disagree concerning the fate of the first Eve. According to one view, the Lord returned her to dust, while in another, she remained alive. She was the cause of the quarrel between Cain and Abel, that led to the first murder (Gen. Rabbah 22:7). This midrash illuminates the problem of a lack of women in humankind’s beginnings. The first murder is depicted as the consequence of a struggle over a woman and indicates that in the future this would be one of the motives for warfare in the world.

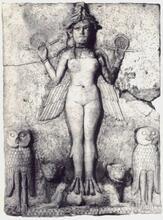

The existence of an additional primordial woman who was rejected by the inhabitants of the land is a motif that was highly developed in folklore, where this woman received the name of Lilith who symbolizes evil and the role of Satan in the world (see Naamah).

Eve, the Mother of All Living

Gen. 3:20 explains that Adam named his wife Eve (Havah) “because she was the mother of all the living [hai],” and the Rabbis gave additional meanings to this name. According to one interpretation, her name comes from the imperative havi (see), for he showed her how many generations she had caused to be lost [because she sinned in eating of the Tree of Knowledge they were driven out of the Garden of Eden, thus bringing death to the world]. According to another interpretation, he called her Havah because “serpent” in Aramaic is hivei. He said to her: “The serpent is your serpent, and you are the serpent of Adam”—the serpent was your serpent, he showed you the fruit and caused you to sin; and you were the serpent of Adam, for he sinned because of you (Gen. Rabbah 20:11). These exegeses show that the primeval sin is inherent in Eve’s name and is bound up with her very essence.

Another midrash argues that the expression “the mother [em, written with an alef] of all living” is to be written differently, with the letter ayin (im—“with”), and that it alludes to the rights of the married woman. If the husband becomes wealthy during the course of the marriage, the wife rises with him [and is not obligated to perform the seven labors that a woman is required to perform for her husband, as enumerated in Mishnah Ketubbot 5:5]. However, if in the course of their marriage the husband loses his property and becomes indigent, she does not descend with him [she does not become a handmaiden; this is why it is said: “of all living,” since a poor man is regarded as dead, and she need not go down with him] (Gen. Rabbah 20:11). In contrast with the preceding traditions that see Eve’s name as the embodiment of sin, this exposition views her name as expressing the rights and standing of all women. The married woman is a separate legal entity from her husband and need not suffer from his economic decline.

The Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud further relates, in the context of Eve’s standing as the mother of all living, that one of the known idols was in the form of a woman nursing an infant. This figure symbolized Eve, who nursed the entire world (BT Avodah Zarah 43a).

“It Is Not Good for Man to Be Alone”

In the midrashic retelling, God created the animals male and female from the outset, but did not do so in the creation of woman, because He foresaw that Adam would complain against her [he would tell God angrily (Gen. 3:12): “The woman You put at my side”]; He therefore waited until Adam himself requested that she be created. God had all the cattle, birds and wild beasts pass before Adam two by two, and man gave them their names. Adam said: “Each one has a mate, but I do not have a mate?” Once he demanded this with his own mouth, immediately (Gen. 2:21), “the Lord God cast a deep sleep upon the man; and, while he slept [...]” (Gen. Rabbah 17:4). In this midrash, Eve’s creation is part of God’s initial plan of creation and part of the nature of the world. Just as all the living creatures were created male and female, so, too, God intended to create man. Eve’s creation was delayed for educational reasons, so that Adam would sense the need for her, and would not be able to later complain.

The Rabbis learn from Gen. 2:18: “It is not good for man to be alone” about the existential condition of every man, and not only of the situation of Adam before the creation of Eve. The midrash asserts: Any man who has no wife lives without goodness, without help, without joy, without blessing, and without atonement. Without blessing, as it is said: “It is not good for man to be alone” [and once Eve was created, it was good for him]. Without help, as it is said (ibid.): “I will make a fitting helper for him” [and the woman who was created was a help for Adam]. Without joy, as it is said (Deut. 14:26): “and you shall rejoice with your house” [“house” means wife; consequently, the wife brings joy]. Without blessing, as it is said [Ezek. 44:30]: “that a blessing may rest upon your home.” Without atonement, as it is said [Lev. 16:11): “to make expiation for himself and his household.” Others add any man who has no wife lives without peace, as it is said [I Sam. 25:6]: “Greetings [literally, peace] to you and to your house”; and without life, for it is written [Eccl. 9:9): “Enjoy happiness [literally, see life] with a woman you love.” It is further averred that man in not whole without a wife, as it is said (Gen. 5:2): “He blessed them and called them Man” [both together are called man, in the singular]. Some assert that one who has no wife lessens the divine image, “for in His image did God make man” (Gen. 9:6), which is followed (v. 7) by: “Be fertile, then, and increase” (Gen. Rabbah 17:2).

These teachings in praise of marriage depict a man who remains alone as one who deprives himself of many boons. Man is portrayed as one who needs a wife to bolster him and aid him, both mentally and physically. The Rabbis recommend living one’s life with a wife, who will bring good, joy and blessing into the house, and who is presented as the one who gives a reason to life. These dicta also have a spiritual and religious aspect: a person cannot observe all the commandments of the Torah, such as the obligation to be fruitful and multiply or that of atonement, without a wife. There is a gradual progress in the order of the dicta, that begin with the recommendation to have a good life, continue with man’s detracting from his wholeness without a wife, and conclude with man’s injuring God by not fulfilling the commandment to be fruitful and multiply.

Despite all these depictions, the Rabbis were also cognizant of the less positive aspects of marital life, and expounded “I will make a fitting helper [literally, a help against him] for him”: if he merited, she is a help; and if not, she is against him.

The Marriage of Adam and Eve

The midrash portrays Eve’s being brought to Adam as an act of divine mating, that was conducted in a festive wedding ceremony, from the descriptions of which we can learn of wedding customs in the time of the Rabbis.

The Rabbis understood the word va-yiven in “And the Lord fashioned [va-yiven] the rib” to mean that God plaited Eve’s hair in a braid around her head, bedecked her as a bride, and thus brought her to Adam; in some places the plaiting of hair is called “binyan.” Additional exegeses greatly glorify the first wedding ceremony. God sat Eve in a wedding canopy (Midrash Tehillim [ed. Buber], 68:4). He decorated her with twenty-four jewels and brought her to Adam, as it says (Ezek. 28:13): “You were in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone was your adornment: carnelian, chrysolite, and amethyst; beryl, lapis lazuli, and jasper; sapphire, tourquoise, and emerald; and gold beautifully wrought for you, mined for you, created on the day of your creation.” Another exposition, however, associates this verse with the wedding canopy: God did not bring Eve to Adam under any single tree, such as a carob or almond. Rather, he made ten wedding canopies for them in the Garden of Eden [according to other views, eleven, or thirteen canopies]. One opinion holds that these canopies had walls of gold and roofs of precious stones and pearls. Another authority adds they even had golden clasps (Gen. Rabbah 18:1).

The Rabbis deduce from “and He brought her to the man” (Gen. 2:22) that God held Eve’s hand as best man and led her to Adam (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Hayei Sarah 2). The Torah thereby teaches proper behavior, that a more eminent person should act as the best man of a lesser one (BT Berakhot 61a).

When Adam saw Eve, he declared (Gen. 2:23): “This one at last [ha-pa’am] is bone of my bones.” The Rabbis derived the word ha-pa’am from pa’amon, bell. Adam said: “This is the one who will beat on me like a bell” [to shake or tap, as the tongue strikes the bell]. Another interpretation derives ha-pa’am from hitpa’amut (excitement): this is the woman who will excite me the entire night (Gen. Rabbah 18:4). In another exposition, when Adam said this, he compared Eve to all the other creatures, for before her creation Adam had engaged in sexual relations with every animal and wild beast, but he was not satisfied until he had intercourse with Eve (BT Yevamot 63a).

In the Rabbinic exegesis of Gen. 2:25: “The two of them were naked, the man and his wife, yet they felt no shame [ve-lo yitboshashu],” yitboshashu is understood as an abbreviation of ba shesh (literally, “come to have relations-six”): Adam and Eve did not wait quietly even six hours before engaging in intercourse (Gen. Rabbah 18:6).

Eve and the Serpent

In the midrashic expansion, the serpent, “who was the shrewdest of all the wild beasts” (Gen. 3:1), cast his eyes on what was not fit for him. The serpent saw Adam and Eve naked, engaging in intercourse in plain sight, and he lusted after Eve. He wanted to kill Adam and then marry Eve. When he was punished, God told him: I intended that you would reign over all cattle and beasts, but now “more cursed shall you be than all cattle and all the wild beasts” (Gen. 3:14); you desired to kill Adam and marry Eve, now “I will put enmity between you and the woman” (Gen. 3:15). What the serpent wanted was not given him, and what he had was taken from him (T Suspected adulteressSotah [ed. Lieberman] 4:17–18; Gen. Rabbah 18:6). According to another tradition, the serpent did indeed engage in intercourse with Eve, who became pregnant and gave birth to Cain (see below, “Now the Man Knew His Wife Eve”).

The Rabbis were intrigued by the question of how the serpent succeeded in enticing Eve to transgress the word of God. They used Eve’s sin, the first transgression on earth, as a model for all human sins, and by means of this initial trespass they seek to understand what motivates people to sin.

According to one tradition, Eve was led astray because she made a restrictive measure for herself that became more important than the actual prohibition. While God had only forbidden Adam and Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge (Gen. 2:17): “but as for the tree of knowledge of good and bad, you must not eat of it; for as soon as you eat of it, you shall die,” Eve added an additional limitation, and told the serpent that God had also forbidden touching it (Gen. 3:3): “Of the fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden God said: You shall not eat of it or touch it, lest you die.” The serpent saw that Eve added things and pushed her against the tree. He said to her [jestingly]: “Here, you have died!” He also told her: “Just as you did not die by touching it, so, too, you shall not die by eating of it” (Gen. Rabbah 19:3).

According to another tradition, it was Adam who added this restrictive measure: he heard the prohibition from God, but when he told Eve about it, he decided to add a further limitation, and expanded the prohibition to include touching the tree. Eve consequently thought that the prohibition included both eating from and touching the tree. The serpent said to himself: Since I cannot cause Adam to sin, I will go and lead Eve astray. He went and sat with her and talked a lot with her. Eve repeated what Adam had told her (Gen. 3:3): “It is only about fruit of the tree in the middle of the garden that God said: You shall not eat of it or touch it, lest you die.” The serpent heard what Eve said, and realized he had a pretext to deceive her. He told her: “If you say that God commanded us not to touch the tree, why, I touch it and I do not die! You, too, if you touch it, will not die.” What did the wicked serpent do? He then stood and touched the tree with his hands and his feet and shook it until its fruits fell to the earth. He said to her: “Here, I touched the tree and I did not die, and if you touch it, you will not die.” He added: “Here, I eat from the tree and I do not die, and if you eat from it, you will not die” (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan [ed. Schechter], version A, chap. 1; version B, chap. 1). This midrash reveals dilemmas from the life of the Rabbis, who aspired to live in accordance with the laws of the Torah, including prohibitions that pertain to all realms of life.

The midrash presents man as inclined to surround himself with all manner of restrictive measures in order to distance himself from the actual prohibitions. This aspect of human nature is already reflected in the first prohibition that Adam and Eve were given. The first tradition portrays Eve as setting forth such a restrictive measure for herself and as forgetting the primary prohibition, while the second has Adam trying to protect Eve by means of such a measure, and Eve as precisely repeating the prohibition that was given to her. Both indicate the danger inherent in the making of restrictive measures that cause the initial prohibition to be forgotten.

Another approach sees as the basis of this sin the jealousy that the serpent aroused between Adam and Eve, on the one hand, and God on the other. This interpretation is based on what the serpent says in Gen. 3:5: “but God knows that as soon as you eat of it your eyes will be opened and you will be like God, who knows good and bad.” According to the midrash, which strengthens this direction, the serpent began by slandering his Maker. He told Eve: “He ate of this tree and created the world, but to you He says, Do not eat from it, so that you will not create other worlds. Everyone hates his fellow craftsman. Hurry and eat from the tree, before He creates other worlds, that will rule you” (Gen. Rabbah 19:4).

Yet another midrashic tradition has the serpent telling Eve: “Know that this is only jealousy. Just as God can create a world, so you, too, can create a world. Just as He can kill and keep alive, so you, too, can kill and keep alive” (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, version B, chap. 1). These traditions ignore the temptation posed by the fruit, instead focusing on a fundamental issue: man’s desire to control his fate and the world. Man wishes to sense mastery over his life and do whatever he pleases, without limits, and thereby resemble God, or even to be God himself.

In another hermeneutical exposition, the sin was a consequence of not believing that God’s aim is to act for man’s benefit. In order to explain this, the Rabbis cite the parable of a king who married a woman and allowed her to control his gold and silver and all his possessions. He told her: “Here, all that I have is in your hands, except for this barrel, which is full of scorpions.” An old woman came to the wife to borrow some vinegar, and asked her: “How does the king treat you?” She [the queen] answered: “The king treats me well. He lets me rule over his gold and silver and all that he possesses, except for this barrel that is full of scorpions.” The old woman said to her: “But all his jewelry is in this barrel; he wants to marry another woman and give them to her!” The wife put forth her hand and opened the barrel, the scorpions bit her, and she died (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan version B, chap. 1.). According to this parable, God’s intent was to give man all the good in the Garden of Eden and keep the evil from him. The serpent, however, engendered distrust of the Lord in Eve’s heart, thus causing her to sin.

These three different explanations of Eve’s sin offer fundamental reasons for what leads humans to sin. Transgressions result from the erecting of unnecessary restrictive measures; from man’s desire to feel like God, with mastery over his life; or from man’s lack of trust in God’s desiring only the best for man when He sets limitations. The use of Eve’s sin as a paradigm for human wrongdoing limits her personal guilt. The transgression is not a result of her having an unstable personality, of her being one who is easily tempted, or by the very fact of her being a woman. Eve is presented here as Everyman, and she reveals the shortcomings of every human being.

Eve Tempts Adam

Eve ate from the fruits of the tree and realized that she was not harmed. She said: “All those things that Adam, my master, forbade me are false.” In another exegetical exposition, after Eve ate of the Tree of Knowledge, she saw the Angel of Death approaching her. She said: “Here I am, about to leave the world; the Lord will create another Eve for Adam in my stead. What shall I do? I will cause him to eat with me.” Adam ate of the fruit of the tree, his eyes began to open and his teeth to be blunt within his mouth [i.e., he began to suffer]. He demanded of Eve: “What is this you have given me to eat? Have you eaten and given me to eat from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?” He concluded: “Just as my teeth have been blunted, so, too, shall the teeth of all creatures be blunted” (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan version B, chap. 1).

The exegetes attempt to understand how Eve succeeded in tempting Adam to transgress the divine mandate and eat of the Tree of Knowledge. One opinion is that this was an act of deception. The Tree of Knowledge was a grapevine, and Eve took “of its fruit” (Gen. 3:6)—i.e., what came forth from the fruit: she pressed the grapes and gave the wine to Adam. Wine is known for its intoxicating quality, which causes people to act without thinking. It is also possible that Adam did not identify this as the fruit of the forbidden tree when he imbibed of the drink that she prepared for him.

Another approach maintains that Eve came to Adam in a rational manner. The wording “with her” in Gen. 3:6: “She also gave some to her husband [literally, to her husband with her]” teaches that Eve thought that a man must cleave to his wife, in life and in death. She challenged Adam: “What do you think, that I will die and another Eve will be created for you? or perhaps, that I will die and you will sit around idle?” In a third exegesis, Eve began to wail at Adam until he ate of the tree (Gen. Rabbah 19:5). These three exegetical positions reflect three different ways of influencing a person, and the Rabbis perhaps saw in them different feminine wiles for persuading men: influence by means of temptation and the blurring of rational deliberation; persuasion by intellectual means; and the exertion of prolonged emotional pressure.

The Rabbis relate that Eve did not give the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge only to Adam, but also fed it to the cattle, beasts and birds, deriving this from the plural in Gen. 3:6: “She also gave some to her husband.” All the living creatures heeded her and ate of it, except for the phoenix. This bird lives for a thousand years, at the end of which fire issues forth from its nest and consumes it, leaving behind an egg, which grows limbs and lives anew (Gen. Rabbah 19:5). This exposition perceives Adam and Eve as reflecting all the creatures in the world. Just as Adam and Eve were to live in the Garden of Eden and be immortal, so, too, all the other creatures. The sin harmed all of creation: it caused the animals, as well, to descend to a lower level and all of them were driven out of the Garden and became mortal. Eve’s standing as the “mother of all the living” acquires a new meaning here, as the one who sealed the fate of all life on earth.

Life after the Sin

Gen. 3:7 relates that after Adam and Eve ate of the Tree of Knowledge “then the eyes of both of them were opened and they perceived that they were naked.” The Rabbis observe: They had a single commandment, and they stripped themselves of it (Gen. Rabbah 19:6). In this exposition, their nudity is an external expression of inner spiritual nakedness. God’s purpose was to give Adam and Eve the possibility of heeding Him and thereby fulfill a commandment, but they lost the only gift bestowed upon them. The commandments are perceived in this teaching as a privilege given to man, and as something that benefits him and covers the nakedness of his soul.

When Adam and Eve perceived that they were naked, they sewed together fig leaves and made loincloths for themselves (Gen. 3:7). In the midrashic expansion, they made themselves three different types of garments: shirts, coats and sheets. And just as they made clothing for the man, they likewise fashioned garments for the woman: hats, girdles and hair nets (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). R. Isaac accordingly applied to this the proverb: “If you acted disgracefully, take a thread and sew” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). This saying teaches the responsibility that every person has for his actions, and that the consequences of immoral behavior are accompanied by physical exertion. The sin of Adam and Eve also brought physical labor to the world, for from then on man would have to toil in order to eat bread.

Evasion of Responsibility

The Torah relates that when the Lord asks Adam if he had eaten from the forbidden tree, he shirks his responsibility and says (Gen. 3:12): “The woman You put at my side—she gave me of the tree, and I ate.” The midrash comments on this that God knocked on the vessel, and found it full of urine (Gen. Rabbah 19:11). When God asked Adam (Gen. 3:11): “Did you eat of the tree from which I had forbidden you to eat?", He gave Adam the opportunity to admit his crime. Knocking on the vessel is an action performed by the potter after he makes the vessel, to examine its durability. Adam’s response, however, reveals his character, which is as repulsive as urine. As this midrash understands the biblical scene, if Adam had taken responsibility for his actions, he might not have been punished so severely.

God then addresses Eve, who places the responsibility on the serpent, saying (v. 13): “The serpent duped me, and I ate.” The Rabbis understand that Eve said: ”The serpent aroused me, obligated me and deceived me” (Gen. Rabbah 19:12). The three means adopted by the serpent emerge from Eve’s statement: seduction, compulsion, and subterfuge.

The Punishment for Eating of the Tree of Knowledge

The Rabbis maintain that all the events depicted in Gen. 1–3 happened on the same day. In the course of a single day, Adam was created, Eve was mated with him, and God brought them into the Garden of Eden; that same day, God commanded them not to eat of the Tree of Knowledge, that very day they sinned, and that same day their punishments were meted out to them (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, version A, chap. 1).

The Rabbis state that in matters of greatness, one begins with the great and proceeds to the minor, but as for curses, the minor precedes the major; this they deduce from the Garden of Eden narrative, since God began with the minor—the serpent—before continuing with the woman, and then concluding with the man, as each in turn was cursed (Sifra, Shemini 1:39).

In the Torah, Eve’s punishment (Gen. 3:16) centers on pregnancy and birth—“I will make most severe your pangs in childbearing; in pain shall you bear children”—and on gender relations: “Yet your urge shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” The Rabbis then expand upon this punishment: “Your pangs” is the anguish of impregnation; “in childbearing” is the suffering of pregnancy; “in pain” is the affliction of miscarriages; “shall you bear” is the pain of childbirth; “children” is the suffering involved in the rearing of children. “Yet your urge shall be for your husband”; a woman's desire is for her husband (Gen. Rabbah 20:6–7). Another tradition asserts that three decrees were issued against Eve: “harbeh,” “arbeh” (that are translated here together as “I will make most severe”), and “your pangs in childbearing”: “Harbeh”—it is painful for the woman at the beginning of her menstrual period; “arbeh”—the first intercourse is difficult for her; and “your pangs in childbearing”—throughout the first three months of pregnancy, a woman’s face is ugly and turns green (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan loc. cit.).

The Talmud asserts that Eve was given ten curses, seven of which are learned from Gen. 3:16: “I will make most severe”—these are the two drops of blood that aggrieve a woman, the blood of menstruation and the blood of virginity; “your pangs” is the anguish entailed in raising children; “in childbearing” is the pain of impregnation; “in pain shall you bear children” is the pain of giving birth; “yet your urge shall be for your husband” is the heartache felt by a woman when her husband sets out on a journey; “and he shall rule over you” is the distress of woman, who desires intercourse only in her heart, while the man can explicitly demand it. To these seven, three more curses were added: the woman is garbed like a mourner, since she must cover her head; she is banished from the company of all men, since she may be married to only a single husband; and she is imprisoned, since she is always at home.

One opinion replaces these last curses with another set of three: she grows her hair like Lilith; she urinates while sitting, like a beast; and she serves as a pillow for her husband during intercourse (since she is underneath him). Other Rabbis, however, deny that these last three are curses, and argue that they are actually complimentary. Long hair enhances woman’s beauty, urinating in this fashion is modest, and in intercourse the female does not exert herself like the male; furthermore, the husband courts the woman until she is willing to marry him (BT Eruvin 100b).

The Talmud states that righteous women “were not included in the decree upon Eve,” that is, the difficulties entailed in pregnancy and childbirth do not apply to them (BT Sotah 12a).

Every curse imposed by God also contains a blessing, and from the curse of Eve the Rabbis learned the secrets of pregnancy and birth. The wording “I will make most severe your pangs in childbearing” teaches that whoever is harbeh [this Hebrew word has the numerical value of 210], I will give him life—every fetus that is in its mother’s womb for 210 days will be viable (Gen. Rabbah 20:6). The Rabbis deduce from the juxtaposition between “in pain shall you bear children” and “yet your urge shall be for your husband” that when a woman is on the birthing stool she tells herself: “I shall no longer desire my husband” [so she will no longer become impregnated and give birth]. God responds: “Return to your urge, return to your urge for your husband” (Gen. Rabbah 20:7). In this context, the Rabbis explain that because the woman vacillated [rifrefah, i.e., considered taking a vow], after giving birth she must bring a fluttering [merufraf] sacrifice [i.e., a minor sacrifice, that flutters like a bird]: “she shall take two turtledoves or two pigeons” (Lev. 12:8). This exposition interprets the curse as a blessing: the goal of God’s blessing is to ensure human existence, and therefore the female’s desire returns after she has given birth (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

Eve’s sin, for the Rabbis, is not limited to her violating the divine mandate and causing Adam to sin, but also includes causing the expulsion from the Garden of Eden and the loss of eternal life that had been promised to Adam and Eve. Female behavior and the commandments incumbent upon the woman express this sentiment, as well. R. Joshua was asked: “Why does a man go forth with uncovered head, while the woman goes forth with her head covered?” He replied: “This is like someone who committed a transgression and is embarrassed before other people, therefore the woman goes forth covered [for she sinned and is ashamed].” He was further questioned: “Why do women go to the corpse first [it was the custom in Judea that women preceded the corpse in a funeral procession, while the men followed the bier]?” He answered: “Because they caused death to come to the world, they go first with the corpse” (Gen. Rabbah 17:8).

Three special commandments were given to woman to atone for her sin: Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah [menstrual purity], the taking of During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah from dough, and the kindling of the Sabbath lights. The commandment of niddah, because Adam was the blood of the world, and Eve brought death upon him, and therefore the commandment of niddah was entrusted to her; the taking of hallah, because Adam was pure hallah for the world, and Eve brought death upon him, and therefore the commandment of hallah was entrusted to her; and the kindling of the Sabbath lights, because Adam was the light of the world, and Eve brought death upon him, and therefore the commandment of kindling the lights was entrusted to her (JT Shabbat 2:6, 5b).

“Now the Man Knew His Wife Eve”

Immediately following the expulsion from the Garden of Eden (end of Gen. 3), the Torah tells of the birth of Cain and Abel (beginning of chap. 4). The midrash connects these two events, and in one explanation, finds a chronological link: the Rabbis state that three wonders were performed that day: all on the same day they [Adam and Eve] were created, they engaged in intercourse, and they produced offspring. Thus, Cain and Abel were born on the very day of Adam and Eve’s creation (Gen. Rabbah 22:2). Another midrash finds a causal relationship here: when Adam saw the fiery ever-turning sword he understood that his sons were destined to be lost in Gehinnom, and therefore abstained from reproduction. However, when he saw that after twenty-six generations Israel would receive the Torah, which is compared to a sword, he decided to produce offspring (Gen. Rabbah 21:9). This exegesis emphasizes that the existence of the human race as a whole has no intrinsic value, save for the merit of Israel that would receive the Torah.

The Rabbis deduce from the statement of Cain’s birth in Gen. 4:1: “And she bore (et) Cain” that the word et is an amplification, since a twin girl was born together with Cain. In the description of Abel’s birth (v. 2): “She then [va-tosef] bore (et) his brother (et) Abel,” the article et appears twice, from which the Rabbis learn that two twin sisters were born together with Abel. The wording “she then [va-tosef]” teaches of an addition to the birth, with no additional impregnation [i.e., a single pregnancy, but multiple births] (Gen. Rabbah 22:3). It therefore is said of the births of Cain and Abel that two ascended [to the bed] and seven descended. The two who ascended were Adam and Eve, and the seven who descended were Adam and Eve, Cain and the twin sister born together with him, and Abel and the two twin sisters born together with him (Gen. Rabbah 22:2).

Cain’s birth was the first “natural” birth. The Rabbinic exegesis of Eve’s statement (Gen. 4:1, based on the translation of Aryeh Kaplan in The Living Torah): “I have gained a male child with the Lord,” involves God in the creation of the male child; before this, Adam was created from the earth, and Eve, from Adam. From now on human reproduction would be “in our image, after our likeness” (Gen. 1:26): no man without a woman, and no woman without a man, and not two without the Shekhinah (the Divine Presence) (Gen. Rabbah 22:2). Cain’s birth symbolized all succeeding births, in which three are always involved: a man, a woman, and the Shekhinah.

The midrash perceives Eve’s statement, “I have gained [kaniti] a male child with the help of the Lord,” as the heartfelt wish of every woman: when a woman sees that she has sons, she says: “Behold, acquired [kanui], my husband is acquired by me” (Gen. Rabbah 22:2). The wife thereby expresses her hope that her husband would now be obligated to her and will not leave her.

Another midrash regards Cain’s birth as unnatural. According to this exposition, Cain was the son of the primeval serpent. The serpent desired Eve, had relations with her, and she became pregnant with Cain. Afterwards, Adam had relations with her, and she became pregnant with Abel. The wording “now the man knew his wife Eve” teaches that Adam knew that Eve was already pregnant. When Eve saw the image of Cain, who is not of the earthly beings but from the supernal, she said “I have gained a male child with the Lord [i.e., the serpent of the Lord]” (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer [ed. Higger], chap. 21).

After the Murder of Abel

According to the midrashic retelling, after Cain murdered Abel, Adam resolved to abstain from relations with his wife and they lived a celibate life for one hundred and thirty years, during which the male spirits were fructified from Eve, who then gave birth, while the female spirits were fructified by Adam and they then gave birth. Eve therefore is called “the mother of all the living,” for she was the mother of all life (Gen. Rabbah 20:11).

Two women, Adah and Zillah, persuaded Adam to change his decision and resume relations with Eve. They came to Adam for judgment after they had abstained from relations with their husband Lamech in the wake of his killing of Cain and Tubal-cain. Lamech did not accept their abstention and demanded that they engage in intercourse with him. Consequently, they came to the tribunal of Adam for judgment. After hearing the women’s arguments, Adam ruled that they must obey their husband, since he killed unwittingly. He told them: “You do what is yours to do, and God will do what is for Him to do.” Adah and Zillah answered Adam with the proverb: “Physician, heal thyself,” thereby hinting to him that he himself must act as he had decreed for them, since he had withdrawn from his own wife for one hundred and thirty years. Adam took their words to heart and returned to Eve, leading to the birth of Seth, the progenitor of the line of Shem (Gen. Rabbah 23:4).

When a child was born to Adam and Eve after the murder of Abel, she called her son Seth, for “God had provided me with [shat] another offspring” (Gen. 4:25). The Rabbis understand “another offspring” as an allusion to the anointed king, the Messiah, who will be from the line of Seth and Ruth the Moabite (Gen. Rabbah 23:5).

The Rabbis learn from (Gen. 4:25) “Adam knew his wife again” that Adam’s desires then increased. In the past, he desired Eve only when he saw her, but now he lusted after her whether he saw her or not (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

The Place of Eve’s Burial

The Torah says nothing regarding Eve’s death and her burial place. The midrash relates that she was buried in Kiriath-arba—so named because the four (arba) Matriarchs are buried there: Eve, Sarah, Rebekah, and Leah (Gen. Rabbah 58:4).

Adelman, Rachel. The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha. Vol. 140. Brill, 2009. See esp. “Adam, Eve, and the Serpent.”

Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian imagination. Westminster John Knox Press, 2002.

Boyarin, Daniel. Carnal Israel: Reading sex in Talmudic Culture. Vol. 25, 77-106. University of California Press, 1993.

Pagels, Elaine. Adam, Eve, and the Serpent: Sex and Politics in Early Christianity. Vintage, 2011.

Stone, Michael E. A History of the Literature of Adam and Eve. Scholars Press, 1992.