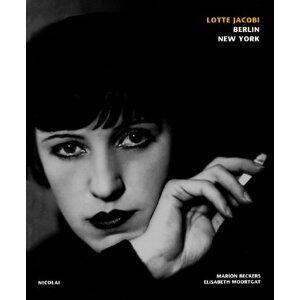

Lotte Jacobi

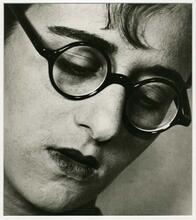

A fourth-generation photographer, German-born Lotte Jacobi became known for capturing her subjects, no matter how famous or iconic, in honest, unguarded moments. Jacobi studied both photography and cinematography before taking over the family business in 1927. Her photography was so highly regarded that Nazi officials offered to make her an honorary Aryan. She refused, fleeing Berlin for New York in 1935. In America, she again became known for her intimate photographs of major cultural figures, including Albert Einstein and Robert Frost. She also experimented with photogenics, exposing photosensitive paper to light to create abstract images. Jacobi was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1976. Four years later at the 1980 convention, she got a press pass, making her the convention’s oldest working press photographer.

In 1935, Lotte Jacobi rejected the Nazis’ offer to grant her honorary Aryan status and fled first to London and then to the United States, where she became one of America’s foremost portrait photographers.

Early Life and Family

The oldest of three children (her sister was also a photographer; her brother died following an accident at age twenty), she grew up in a family of photographers. Her great-grandfather Samuel Jacobi learned his craft in 1839 from Louis Daguerre, the inventor of modern photography. Samuel Jacobi founded a studio in West Prussia that was carried on by his son Alexander; his grandson Sigismund, who moved the studio to Berlin; and in 1927 by his great-granddaughter Lotte. Jacobi studied cinematography at the University of Munich and photography at the Bavarian State Academy of Photography. Jacobi married Fritz Honig in 1916. They had a son, John, in 1917, and the couple separated the same year. They were divorced in 1924. She tried her hand at acting and cinematography before returning to Berlin in 1927 to run her father’s studio.

During the Weimar period, artists, political leaders, scientists, and authors moved in and out of the Jacobi studio to be photographed and to engage in stimulating conversation. The family was active in the leftist social and political movements of the time. Among her satisfied customers were high-ranking German officials. Unaware that she was Jewish, they praised her work as “good examples of Aryan photography.” While some of these photographs from the 1930s remain (among them photographs of Lotte Lenya, Kurt Weill, Peter Lorre, and Kathe Kollwitz), many more negatives and photographic plates were left behind and lost when Jacobi and her son fled Nazi Germany in 1935, shortly after her father died. Her mother later joined them in New York.

While Jacobi’s Jewish heritage as well as her moral and political stance determined the course of her immigration to America, she did not speak much about her past, and many of her friends did not even know that she was Jewish.

In 1940, Jacobi married Erich Reiss, a respected German book publisher who had survived the concentration camps and immigrated to the United States. They enjoyed a happy marriage until his death in 1951.

Photography Career

Jacobi opened a studio in New York and soon was photographing the artists, scientists, political leaders, and literary figures of the day. Among the people she photographed were Albert Einstein, who was a family friend, and prominent Americans such as Robert Frost, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Paul Robeson. She not only photographed the cultural elite, many of them European emigrés, but was one of them.

In 1955, Jacobi moved to rural Deering, New Hampshire, with her son and his wife, Beatrice Trum Hunter. There, with John’s help in 1960, she rebuilt a cabin in the woods, adding on a studio and room to display the work of other photographers. She continued to have many visitors and was a mentor to young photographers.

Her photographs are notable for their intimacy and for the personal qualities that she reveals in the faces of her subjects. Jacobi intended the photograph to reveal the personality of the subject, not of the photographer. While capturing the right angle and light, she engaged her subjects in topics that interested them until they felt at ease and forgot about the camera. While she enjoyed taking pictures of the great men and women of her time, she was not awed by them (“Don’t they get dressed in the morning like the rest of us?”), and took equal pleasure in photographing children in city streets and, later, her neighbors in rural New Hampshire. She experimented with photogenics, a cameraless photography in which she exposed photosensitive paper to light to create abstract images.

In Deering, Jacobi returned to her lifelong political interests, both locally and nationally. She was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1976, and when she forgot to register in time for the 1980 convention, she bartered a press pass from the Concord Monitor. At age eighty-four, she was celebrated as the oldest working press photographer at the convention.

Legacy

Jacobi was awarded an honorary doctorate of fine arts by the University of New Hampshire in 1973, and later an honorary doctorate of humane letters from New England College.

Lotte Jacobi died on May 6, 1990, at age ninety-three in the Havenwood Nursing Home in New Hampshire. She bequeathed forty-seven thousand negatives to the Lotte Jacobi Archives established at the University of New Hampshire, her record of mid-twentieth-century history revealed in the faces of the artists, world leaders, intelligentsia, and ordinary people of America and Europe.

Bacon, Richard M. “Lotte Jacobi.” Yankee (August 1976): 60–91.

Beck, Tom. “‘I Remember Einstein’: A Photographer’s Recollections.” University of Maryland Magazine 7:2 (1979): 6–11.

Beckers, Marion, and Elisabeth Moortgat. Lotte Jacobi: Berlin–New York (1998). Carlson, Martha. “Lotte Jacobi: Still Unpredictable at 89.” Business NH (November 1985): 77–83.

Hunter, Beatrice Trum. Interview with author, March 23, 1996.

Karanikas, Alexander. “Lotte Jacobi’s Place.” New Hampshire Profiles 21, no. 4 (April 1972): 32–78.

Savio, Joanne. “A Visit with Lotte Jacobi.” Women Artists News 2, no. 3 (June 1986): 26–27.

Slade, Marilyn Myers. “Lotte Jacobi.” New Hampshire Profiles 36, no. 1 (January 1987): 38–45.

Vesperi, Maria D. “Lotte Jacobi.” St. Petersburg Times, June 24, 1990.

Warnock, Phyllis K. “Home of the Month.” New Hampshire Profiles 12, no. 10 (October 1963): 35–40.

WWIAJ (1938).