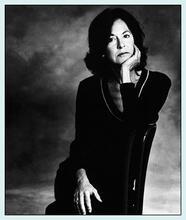

Debra Renee Kaufman

A central voice in sociology, feminist studies, and Jewish Studies over the past fortyyears, Debra R. Kaufman is the founder and former director of the Women’s Studies Program and the Jewish Studies Program at Northeastern University. Her scholarship has spanned topics such as the role of women in Orthodox Judaism, contemporary studies of the Holocaust, post-Holocaust Jewish identity narratives, and contemporary American Jewish identity.

Debra Renee Kaufman has been a central voice in sociology, feminist studies, and Jewish Studies for the past forty years. She has helped to shape the field of Jewish Studies not only through her professional research and scholarship but also through her efforts as the founding Director of Northeastern University’s Women’s Studies Program in 1981 (under her leadership later changed to the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program) and one of the founding directors of Northeastern’s Jewish Studies Program in 1997. As the Director of Jewish Studies, she not only initiated and helped to promote connections with Hebrew College of Boston but also developed and sponsored major conferences on Jewish topics critical to our contemporary analysis of Jews and Jewish life.

Early Life and Education

Born on April 2, 1941, to Ida Hoffman Horwitz and Max Horwitz of Cleveland, Ohio, Kaufman grew up in a poor immigrant Jewish community in Cleveland, with an Orthodox synagogue just up the street from her home. During the postwar years, Cleveland was home to many displaced survivors of the Holocaust. Her parents’ command of Yiddish and her father’s knowledge of at least four other languages led them to help support survivors who relocated to the Cleveland community. Not until many years later did Kaufman turn her scholarly attention to her Orthodox Jewish background and to those two pivotal socio-historic moments in history: the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel.

Kaufman left Cleveland to attend the University of Michigan, where she was recruited into the Sociology honors program and completed her master’s thesis as an undergraduate in her senior year as part of the Detroit Area Study project, a social research training ground and resource for data on the Greater Detroit Area. She met and married Michael Kaufman, a graduate student in literature; when they left for his first academic appointment at Cornell University, she had completed her master’s degree and almost all her course work for the PhD. At Cornell she worked as a Research Associate in an interdisciplinary research group on poverty, with a special emphasis on women. Limited by the research she could do without a PhD, she applied for and received a university scholarship to the doctoral program at Cornell. As a graduate student, she was active in the nascent Women’s Studies Program, one of the first in the country.

After her children, Alana and Marc, were born, Kaufman left Cornell for the State University of New York at Albany, where her husband joined the English Department and she joined an interdisciplinary undergraduate residential college program as part of a larger Ford Foundation initiative within the University. As a lecturer in the James Allen Center, which was combined students’ senior year of high school with their first year of college to complete a BA in 3 years, she helped develop a four-year interdisciplinary curriculum for the program, contributed to the newly developing women’s studies program in the College of Arts and Sciences, completed her PhD in 1975 from Cornell, and spent some time as a political activist testifying before the State legislature on women in academia.

Pioneering Women’s Studies

In 1976, Kaufman became an assistant professor at Northeastern’s Sociology and Anthropology Department and went on to become the founding Director of Women’s Studies at Northeastern. During her tenure as Director, Northeastern became one of the six schools to establish the highly touted interdisciplinary Graduate Consortium in Women’s Studies, first housed at Radcliffe College and currently at MIT.

Kaufman’s first book, Achievement and Women (1981), was one of the first full-length books analyzing the ways in which women’s achievements were limited, confined, and defined in the public sphere. It was one of the first major feminist methodological and theoretical critiques of the male models and measures of achievement that were commonly used in the disciplines of psychology and sociology. The monograph was one of the first feminist books to be nominated by the American Sociological Association for the prestigious C. Wright Mills award for notable contributions to sociological thought. Receiving an honorable mention, it foreshadowed the growing influence of feminist work in the social sciences.

Kaufman’s research on newly orthodox Jewish women and the publication of her book, Rachel’s Daughters: Newly Orthodox Jewish Women (nominated for the Jesse Bernard Sociologists for Women in Society Award and the E.H. Cooley Social Psychology Award), marked the beginning of her work as a feminist scholar in the field of Jewish studies. Kaufman argued that the embrace of Jewish Orthodoxy by these women (one-third of whom defined themselves as feminist) came at a time of rapid social change in sexual and gender expectations. However, this change occurred without a similar structural shift in the public or private sphere that supported gendered power imbalances and patriarchy.

Post-Holocaust Identity Narrative and Identity Studies

Following her work on Jewish Orthodoxy, Kaufman brought her methodological and theoretical concerns to the contemporary study of the Holocaust, analyzing the links among and between history, memory, narrative, and identity. She commissioned a group of feminist writers whose multidisciplinary perspectives brought new lenses to the study of the Holocaust to write about the ways in which the absence of women in Holocaust scholarship affected our understanding and analysis of Holocaust history, as well as our contemporary memory of it. This work culminated in a guest-edited volume for the journal Contemporary Jewry; Kaufman’s lead article analyzed the paucity of research among sociologists on and about the Holocaust.

Kaufman’s research on post-Holocaust Jewish identity narratives among young adults in both the United States and Israel aligned well with her interest in contemporary identity politics and identity studies. In part provoked by disagreements among those who designed and executed the 2000 National Jewish Population Study, conflicting interpretations about the socio-demographic trends (and the tensions among researchers about what constitutes the core and the periphery of the U.S. Jewish population) generated a slew of special conferences and a multitude of sessions within the Association for Jewish Studies that brought into focus the thorny academic and policy question of who counts as Jewish when counting Jews.

In response to the ongoing debates, Kaufman was asked to write a review and critique of the identity literature for a chapter in the Cambridge Companion to American Judaism. In “The Place of Judaism in American Jewish Identity,” Kaufman turned Jewish identity research on its head, challenging the assumption that Judaism may not be at the heart of contemporary Jewish identity. Kaufman provided a critique of the identity literature from a feminist perspective that assumes that all our theories are fluid, that our categories of analysis are never stable, and that new theories emerge when we can no longer explain experience in conventional terms. In this critical overview, she specifically addressed the relationship between qualitative and quantitative research, arguing that qualitative work provides important responses, meanings, and challenges to issues raised by social demographers. Such responses, she stressed, have the potential to move us, as in the case of the erosion/survival debates, beyond policy and institutional concerns about growth or decline to a new level of academic conversation about the meaning and measure of Jewish continuity and its related research corollaries: secularity, ethnicity, authenticity, and religiosity. Since all social science research is limited by the kinds of narrative discourse we bring to it, she argued that demographic trends in exogamy and “assimilation” reflect not only an “erosion” or “growth” of population size and composition, but also tensions about the measure and meaning of Jewish identity and the development and maintenance of consensus on core Jewish values. Therefore, she concluded, whether we see erosion or resilience in our research depends on how a study is designed, what categories are used, how the data are collected, and what interpretive framework is presented for its analyses and ultimately its conclusions. In this sense, she made clear, it matters not if we are qualitative and/or quantitative in our approach but rather where we enter the conversation, why we see it as important, and to what end we will tell our research stories.

Kaufman’s work on post-Holocaust Jewish identity narratives among young adults preceded and foreshadowed some of the findings in Pew’s long-anticipated 2013 National Survey A Portrait American Jews. Her work was among the first to provide a glimpse into the motivations and ways in which those who identify as Jewish but do not identify with institutional religion or religion per se express those identities. Kaufman’s qualitative interviews fleshed out some of the socio-demographic patterns of the almost one-third of millennial Jews whom Pew identified as JNRs (Jews of No Religion): e.g., the importance of the Holocaust to their Jewish identities, the pride they take in being Jewish, and the varied ways in which they express being and doing Jewish. Based on her own work, Kaufman suggests that Judaism or religion itself (or perhaps more accurately, institutional religion) may increasingly be less important as the key component of one’s expression of Jewish identity but not necessarily of being Jewish. In their own voices and their own experiences, young adults in her research who self-define as Jewish offer a myriad of ways to express what being Jewish means to them, and for most that is outside religious institutions. In her influential article “The Circularity of Secularity: The Sacred and the Secular in Some Contemporary Post- Holocaust Identity Narratives,” Kaufman elaborated on the socio-historic connections between the sacred and the secular and how this affects the ways in which we understand both the meaning and the measure of religion in the study of religious identities today.

Kaufman served from 1983 to 1988 on the Advisory Council for the Program in Women's Studies at Princeton University. She has been recognized for her numerous academic achievements, including serving as Visiting Scholar at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, as Visiting Research Scholar at the Murray Research Center at Radcliffe College, and as a Mellon Fellow Seminar Participant at the Center for Research on Women, Wellesley College. In 1987, she was selected to be the twenty-third annual Robert D. Klein lecturer at Northeastern University in recognition of her outstanding scholarly achievement, professional contribution, and creative classroom activity. She received the highest honor of recognition from Northeastern University in 1995 when she was selected as Matthews Distinguished University Professor, with a lifetime title for her outstanding scholarly achievements and professional recognition beyond the University. Kaufman has remained professionally active since her retirement as Professor Emerita of Sociology and Matthews Distinguished University Professor from Northeastern University.

"Decentering the Study of Jewish Identity: Opening the Dialogue with Other Religious Groups." Sociology of Religion 67, no. 4 (2006): 365-85 (with Harriet Hartman).

"Demographic Storytelling: The Importance of Being Narrative." Contemporary Jewry 34, no. 2 (2014): 61-73.

“From Course to Dis-course: Mainstreaming Feminist, Pedagogical, Methodological and Theoretical Perspectives.” In The Handbook of Feminist Research: Theory and Praxis, edited by Sharlene-Hesse Biber, 659-675. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 2012 (with Rachel Lewis).

"The Circularity of Secularity: The Sacred and the Secular in Some Contemporary Post-Holocaust Identity Narratives." Contemporary Jewry 30, no. 1 (2010): 119-39.

“Post-memory and Post-Holocaust Jewish Identity Narratives.” In Sociology Confronts the Holocaust, edited by Judith Gerson and Diane Wolf, 39-54. Duke University Press: Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

“The Place of Judaism in American Jewish Identity.” In Cambridge Companion to American Judaism, edited by Dana Kaplan, 169-186. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

"Measuring Jewishness in America: Some Feminist Concerns." Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies & Gender Issues 10, no. 10 (2005): 84-98.

Achievement and Women: Challenging the Assumptions. New York: The Free Press, 1982 (with Barbara Richardson).