Feminist Jewish Ritual: The United States

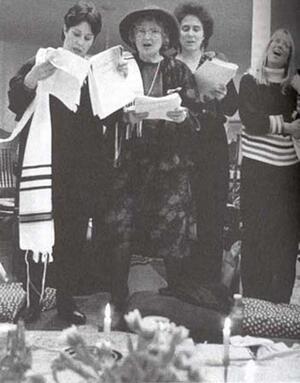

Feminist seders have provided an important context for developing women’s spirituality. In 1975, a group of Israeli and American women decided to create their own Passover seder based on their experiences as Jewish women. Now an annual event held in Manhattan, it has been attended by Esther Broner, Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Bella Abzug, Grace Paley and several other "Seder Sisters" who have played important roles in the development of Jewish feminism. Shown here are Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler and Letty Cottin Pogrebin at the Women's Seder in 1991.

Photo: Joan Roth

Ritual behavior is one of the fundamental pillars of Judaism, and of all religions, whose concern is precisely with ultimate meaning and purpose. Men in normative (rabbinic) Judaism have far more access to the sacred through personal and communal ritual than do women, in terms of sacralization of the body, family and public ritual, marriage and divorce, and much more. Jewish women have always elaborated rich sets of rituals with which the sacralized their daily lives, life-cycle events, and holidays, but these rituals did not enjoy the status of male rituals. Over the past several decades, Jewish feminists have elaborated a host of new rituals for women that have achieved remarkable acceptance and attained normative status. They have gained access to male-identified rituals, developed a wide variety of new rituals, and feminized core male rituals.

Ritual is an act or a set of actions that employs symbols meaningful to the participants in a formal, repetitive, and stylized fashion. Ritual frames significant moments and important new realities. It effects transition from one state of being to another, as in weddings, funerals, or conferral of degrees and is one of the most fundamental ways that humans mark meaning in their personal lives and in the lives of their families and societies. In part, ritual responds to primal human terror that the universe is not inherently ordered and that human existence is ultimately physical and nothing more. Its power lies in the fact that it addresses and engages the body. In the words of the anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff, “Rituals persuade the body...; [in ritual] the entire human sensorium [is involved] through dramatic presentation.”

Ritual behavior is a primal human need and its expression is universal and innate—witness how young children ritualize accidental behaviors at bedtime, a time of transition from waking to sleep, by insisting on their subsequent precise repetition. It is one of the primary ways an individual or a culture conveys understanding of self to itself or to others and is one of the chief means of conveying that message to future generations: ritual is a language, even—or perhaps especially—when not accompanied by words. As the anthropologist Joseph Campbell wrote, “Ritual is mythology made alive.” Thus, ritual transmits tradition and can be a powerful agent of cultural conservation. However, precisely because it is “alive,” because of the dynamic human need it addresses, and because material and cultural circumstance change, ritual is constantly being invented, sculpting new meaning for a changed present and for the future. Ritual, therefore, can also be a powerful vehicle for social and cultural change.

Gendered Difference in Traditional Jewish Ritual Observance

Ritual behavior is one of the fundamental pillars of Judaism, and of all religions, whose concern is precisely with ultimate meaning and purpose. Men in normative (rabbinic) Judaism have far more access to the sacred through personal and communal ritual than do women. Rabbinic law (The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah), requires males to don ritual garments (Fringes attached to each of the four corners of a special garment worn to fulfill a Biblical precept.zizit, Four-cornered prayer shawl with fringes (zizit) at each corner.tallit), which symbolically represent all 613 commandments the rabbis say are prescribed by the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah. It requires males over age thirteen to strap miniscrolls containing key verses of the Torah to the head and arm (phylacteries, or Phylacteriestefillin) and to make repeated signs of the letter shin, which represents one of God’s names, with the straps, thus literally binding themselves to Torah and emblazoning God’s name on their bodies.

A ritualized way of shearing hair, based on Leviticus 19:27, leaves the “corners” of the male head conspicuously uncut (pe’ot). Interpretation of the same Biblical verse leads to the growth of full, untrimmed beards that characterize traditional (in particular, ultra-Orthodox) Jewish men. Traditional practice requires ritual covering of the male head as a sign of respect to God, and certainly when performing sacred functions, like praying, eating, and making blessings over other sanctified acts. The only time that ritual bodily cutting, otherwise anathematized by Biblical sanction—the highest level of authority in the rabbinic system—is not only allowed but enjoined in Judaism is ritual circumcision of males Circumcisionberit milah, performed as a sign of covenant with God, significantly, on the male organ. These ritualized behaviors effectively sacralize the male body, making it a carrier of the sacred and a vehicle for public demonstration of connectedness to God and Torah.

There is no analogous sacralization of the female body in classical, rabbinic Judaism. On the contrary, such quintessentially female biological functions as menstruation and childbirth plunge women into a state of ritual impurity, Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah [see also Female Purity], meaning “separate,” “outcast,” “ostracized.” Although technically all Jews are considered ritually impure since loss of the sacrificial system of purification in the Temple, niddah is by far the most elaborate of all the functional remnants of the purity laws, and the one with the greatest behavioral consequences, requiring sexual abstinence and physical separation of the (presumably, though not always) married couple for a minimum of twelve days a cycle, and even longer after a birth. Women are seen as carriers of impurity, with traditional men eschewing such seemingly mundane behaviors as handshakes with women. Various halakhic sources deem women’s voices sexually seductive to men, which leads to women being barred from singing in mixed-gender settings and in ultra-Orthodox circles, even from speaking at conferences or other public settings. Women’s faces have been banished from sales catalogs and death notices or defaced on ads in these circles; even women’s names have been deleted from wedding invitations and death notices. Female head covering, which halakhah enjoins for married women only, is not, like that of men, referenced to God. Rather, it signals sexual unavailability to any male but the husband and derives from androcentric reduction of women to sexual objects for (heterosexual) men.

The extensive world of family and public ritual in classical rabbinic Judaism is also a male preserve. By religious law or entrenched social custom, such fundamental acts as sanctifying the wine and ritually cutting and blessing the bread on the Sabbath and festivals (Lit. "sanctification." Prayer recited over a cup of wine at the onset of the Sabbath or Festival.kiddush, hamotsi), performing the ritual which formally ends the Sabbath and holidays (Lit. "distinction, division." The blessing recited at the close of the Sabbath and Festivals to indicate the distinction between holy and ordinary days.havdalah), lighting Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah candles, leading the A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder, dwelling in the Lit. "booths." A seven-day festival (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei to commemorate the sukkot in which the Israelites dwelt during their 40-year sojourn in the desert after the Exodus from Egypt; Tabernacles; "Festival of the Harvest."sukkah (tabernacle), enjoined on the holiday of Tabernacles, and blessing and waving the Four Species during this holiday, counting in a prayer quorum (The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan), leading services, making blessings over the Torah reading (Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyot), public reading of the Torah and dancing with the Torah scroll on the Festival of the Torah ( Lit. "rejoicing of the Torah." Holiday held on the final day of Sukkot to celebrate the completing (and recommencing) of the annual cycle of the reading of the Torah (Pentateuch), which is divided into portions one of which is read every Sabbath throughout the year.Simhat Torah ), are all restricted to men in rabbinic law and practice, although there is rabbinic debate about whether women may perform these acts voluntarily or in female-segregated space, and if so, whether they may say the traditional blessings on them.

The rabbinic marriage ceremony enacts marriage through the husband, literally the “master” (baal), acquiring from the woman’s father or other male guardian exclusive rights to his wife’s sexuality and reproductivity through the rituals of The act whereby a person voluntarily obtains legal rights over an object.kinyan (acquisition) and kiddushin (sanctification), while she remains passive but for accepting a ring of minimal value to signal acquiescence. This ritual is entirely unilateral: the wife has no similar, exclusive claim to her husband’s sexuality or reproductivity, nor does she marry him; rather, she is married to him. Kinyan and kiddushin are the origin of and cause for iggun, women chained in marriage against their will (Agunot) because a husband refuses or is unable to give a Writ of (religious) divorceget (rabbinic divorce). Because rabbinic marriage is unilateral, enacted by the husband, so is rabbinic divorce, in which the wife is divorced—acted upon (objectified)—but does not herself divorce her husband. Feminists have excoriated this situation, condemning kinyan and kiddushin as inherently degrading to women as well as responsible for the plague of iggun, which regularly entails extortionist demands by husbands, facilitated by rabbinic courtes, for a halakhic divorce (get) to be given. Feminists also bemoan the lack of mutuality in divorce rituals even when these proceed without such abuse.

While halakhah obligates women to observe the laws of the Sabbath, festivals, and mourning, especially the prohibitions (“negative mitzvot”), and all those concerning the ritual diet, there are only three female-specific rituals in rabbinic Judaism. These are: During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah (-removing and burning a portion of dough before it is baked), nerot (lighting the Sabbath and holiday candles), and observing the laws of niddah, which culminate in the woman’s immersion in a ritual bath (Ritual bathmikveh), after which sexual relations between husband and wife may resume. In fact, however, anyone who bakes is obligated to the dough ritual, and in the absence of a woman, men are obligated to light holiday candles, making the only true female-specific rituals those surrounding uterine or vaginal bleeding, with its attendant negative connotations in this system. By contrast, men’s immersion in the mikveh is voluntary and is performed to ready men for the Sabbath, holidays, or other sacred pursuits, such as Torah study or hand writing sacred scrolls. This leads to the feminist plaint that through mikveh, men ready themselves for God and women ready themselves for men.

Traditional Jewish Women's Ritual, Its Fate in Modernity, and Feminist Innovation

Over the centuries, Jewish women across the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora and in the Land of Israel elaborated rich sets of rituals with which they sacralized their daily lives, major life-cycle events, and holidays. Intensely meaningful and authoritative to them, no less so than rituals ordained by halakhah, these rituals did not enjoy the status in the larger community of those sanctioned by the rabbis: they remained “women’s” rituals, while rabbinic rituals are seen as “Jewish.”

The world of female ritual was almost completely obliterated in modern times as women’s forms of spiritual expression, considered unlearned and superstitious in rabbinic circles, were also condemned in emerging modern variants of Judaism as “Oriental,” and a threat to Jewish efforts to achieve equality and social acceptance in non-Jewish society. As a result, the earliest wave of Jewish feminists perceived only the paucity of normative ritual for women in Judaism and many left the community on this account. But this paucity, the negative associations of some existing ritual, and the utter male-centeredness of most ritual in rabbinic Judaism also became the prime area of engaged protest and the spur for creative adaptation and innovation by those who have founded feminist Judaism.

In the past half century or so, feminists have elaborated a host of new rituals for women that have achieved remarkable acceptance and attained normative status. Some of these, like the Lit. "daughter of the commandment." A girl who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbat mitzvah for girls (actually initiated by the founder of Reconstructionism, Mordecai Kaplan, in 1922), parallel the established ritual for boys, celebrating attainment of the age of adult responsibility for the commandments of Judaism through such public acts as Torah and haftarah reading, leading services, and giving a lecture on the weekly Torah portion (devar Torah), and adopting for girls the same age for this onset—13—that halakhah assigns for boys, rather than the age (12) it assigns for girls.

Complementarity—appropriating male-identified ritual for females—is not always possible or desirable, however. A prime example is feminist birth rituals for girls. In traditional Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi practice, the birth of a daughter is marked by the father reciting blessings over the Torah in the synagogue on the Monday, Thursday, or Saturday (days on which the Torah is read, in a The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan), immediately following the birth, at which point he names the baby, usually in the presence of neither mother nor child. The flagrant imbalance between this modest ritual and that of the Biblically ordained mitzvah of berit milah for boys, which is treated as the most significant of events and made the occasion of elaborate celebration, was one of the first that feminist Jews addressed. The suggestion of ritual rupture of the hymen as a physical analogue to circumcision never gained traction. Rather, feminists have created other ceremonies to celebrate the birth of girls and initiate them into the community, such as immersion of the baby in a mikveh, recalling Biblical traditions by washing her feet as a sign of welcome, wrapping her in a prayer shawl, and lighting candles.

Some have adopted or adapted long-established Middle Eastern (Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi), Bukharan, Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardi, or Italian rituals for the birth of girls, called zeved habat (the gift of the daughter). These often-elaborate rituals were held at home but also in the synagogue; mothers and other female relatives participated, and the rituals have their own liturgies featuring the names of the matriarchs, published as separate texts and also appearing in the standard prayer book (such as the current Spanish-Portuguese prayer book). Birth ceremonies and some form of bat mitzvah for girls have become ubiquitous on the Jewish scene, including within Orthodoxy and ultra-Orthodoxy, attesting to the strength of the feminist critique and the degree to which it has been internalized in a remarkably short time, even by those who claim to reject feminism and the larger culture from which Jewish feminism derived its impulse.

Egalitarianism and Feminism

The first Jewish feminist to identify herself as a theologian, Judith Plaskow has created a distinctively Jewish theology that is at once academically rigorous, politically leftist and firmly woman-centered. The best known Jewish feminist theologian in both Jewish and non-Jewish circles, she appears here in 2004.

Photographer: Martha Ackelsberg

Institution: Judith Plaskow

In the 1970s, the first phase of feminist Judaism in the United States focused on equality: gaining access to and appropriating male-identified rituals and rights, such as donning sacred garments and counting in a prayer quorum. Innovation, however, has become a predominant feminist Jewish expression. In the metaphor of the feminist Jewish theologian Judith Plaskow, feminists want to bake a new pie rather than just get a piece of the old one. The quest for equality, as Plaskow, Riv-Ellen Prell, and others argue, is inherently inegalitarian because women seek to perform male-identified roles recognized as traditional and “authentic” (in the feminist critique, thereby becoming “honorary men”), but men do not value or appropriate traditionally female rituals or spirituality.

The quest for equality—or egalitarianism—is also assimilatory, since ritual and spiritual traditions developed by women are seen as inferior and unworthy of perpetuation, while egalitarianism is posited as a more evolved, higher, religious expression, which women, therefore, must accept; feminism, in this view, is merely a way station on the road to egalitarianism. Egalitarianism, these feminists assert, is based on and reinscribes male normativeness in Judaism, while suppressing specifically female spiritual expression. This situation is analogous to that of Jews or other minorities seeking equality who adopt the majority culture but forsake their own. Just as Jews have moved away from seeking only equality in the larger society to seeking both equality and continued specific, Jewish identity, Jewish feminists have evolved from merely adopting male-identified ritual to also elaborating a specifically female ritual expression.

Thus, while women in all the movements but Orthodoxy (and even this exclusion is no longer total) now discharge the same traditional functions as men, a host of new rituals have been created to mark female experience. These include rituals for menarche, menopause, pregnancy, labor, birth, infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth, abortion, adoption, weaning, hysterectomy, and attaining older-age wisdom; women-centered rituals for marriage and divorce, whether conducted under traditional or innovative auspices; and coming out ceremonies for lesbians. All such rituals, of course, have liturgies, which are in the process of becoming standardized, as rabbis or other functionaries use them.

Many of the above-mentioned rituals celebrate female biological functions. Feminists have rejected the claim that this defines women biologically, diminishing women’s full humanity, as patriarchal culture historically has done. Rather, they argue, these rituals recognize the crucial importance of embodiment—as defined by feminists—and assign positive value to functions that androcentric rabbinic culture ignored or despised. They have provided ways to affirm the female Jewish body in a religion that blesses such other bodily functions as bladder and intestinal evacuation but neglected to direct formalized, sacralized awe, wonder, and blessing at menstruation and childbirth.

Integrating Feminism into Mainstream Judaism

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Jewish feminists began to develop a repertoire of new feminist ritual. Yet they simultaneously sought a "usable past" within Judaism, so as to seamlessly link their own ritual creativity to the body of Jewish tradition. This Tashlikh ceremony in Riverside Park in New York City was sponsored by MA'YAN: The Jewish Women's Project. The cantor is Naomi Hirsch.

Photographer: Joan Roth

Feminists have also modified existing rituals to reflect women’s full personhood in Judaism, for example by fashioning egalitarian marriage and divorce ceremonies for heterosexual women and for lesbians by adapting rabbinic partnership law, which, written in the expectation that both parties are men, protected both equally, or by using the laws of vows and their renunciation for marriage and divorce, respectively, or by innovating other methods.

Feminists have created women’s Passover seders and ushpizin ceremonies in the Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.sukkah to welcome the Biblical matriarchs, paralleling the traditional invitation to the patriarchs. Some feminists have reclaimed mikveh, dismissed vehemently by many, particularly in the first phase of feminist Jewish impulse, as irredeemably sexist, choosing to see in its waters a primal symbol of creation and nurturing, reminiscent of amniotic waters, whether in traditional or innovative use of the mikveh. Innovative uses of the mikveh include affirmation of female biological functions with no reference to men or to sex; to mark beginnings or ends, such as birth, menarche, or divorce; or in rituals for physical or emotional healing after sexual abuse or domestic violence.

One of the first innovations that feminists enacted was reclamation of The new moon; the first day of the month; considered a minor holiday, especially for women.Rosh Hodesh, the new moon (celebration of the new month), which was traditionally a semi-holiday for women, for avowedly feminist purposes. Feminist Rosh Hodesh groups have become a chief venue for creating and transmitting new rituals, including birth ceremonies for girls and adult bat mitzvahs and for feminist consciousness-raising, which can yield an experience of what anthropologists call “communitas,” radical bonding of those sharing a liminal state or moment.

Feminists have also reworked the language of liturgy and ritual by including the names of the matriarchs, sometimes alone or with the names of the patriarchs; feminizing God language or creating grammatically neutral forms to address and name God; and by changing divine images from ones of hierarchy and dominion to ones of immanence, creation, and nurturing. Some have reclaimed and reworked traditional forms of women’s spiritual expression, such as Yiddish-language Tkhines, private, often intensely personal petitionary prayers that Ashkenazi women recited at candle lighting, before and after immersion in the mikveh, and with baking and scores of other sacred or sacralized acts, such as making memorial candles for the dead or celebrating the eruption of a baby’s first tooth.

Feminists have also feminized core male rituals, for example by including the participation of the mother and other women in the traditional circumcision ritual. They have also created new rituals to mark the birth of boys, in addition to ritual circumcision, in which the male organ is not the center of attention or sacralization. In this, they have brought feminist ritual creativity to the religious socialization of men, a major new phase in feminist Judaism and Judaism altogether.

Resources and Their Significance

There are now many published and on-line collections of feminist Jewish liturgies and rituals, such as a guide to birth ceremonies compiled by the New York branch of the National Council of Jewish Women, Ritual Well, Penina Adleman’s Miriam’s Well, Marcia Falk’s The Book of Blessings, and the two-volumes of Lifecycles, edited by Rabbi Debra Orenstein, which also include a guide to producing successful new ritual. The JOFA (Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance) Journal regularly publishes suggestions for birth, bat mitzvah, wedding, and other rituals that accord with halakhah. Vanessa Ochs’ Inventing Jewish Ritual is a major addition to the literature, with both analysis and reproduction of liturgical texts used in various rituals, feminist and otherwise; it also reflects on the phenomenon of Jewish ritual innovation in the United States in recent decades, applying theoretical insights from cultural anthropology and the new field of ritual studies and laying out dozens of new practices and their meaning for their practitioners, with a participant-observer’s sympathetic assessment of the phenomenon and its significance in any consideration of the vitality of contemporary American Judaism.

All this production testifies to the existence of a reading and practicing constituency and to a process of standardization underway, showing how what was once, even quite recently, innovative and new becomes established, self-evident, and normative. Feminists have laid claim not just to perpetuating Judaism as produced by male authorities but to fashioning or producing it themselves, in female image, as men historically have fashioned Judaism in male image. This effort is not, as it was in pre-modern Judaism and is still the case with traditional women’s spiritual expressions in Orthodoxy and ultra-Orthodoxy, contained in a separate sphere but is intended to reshape Judaism as a whole. This feminist work is a prime example of ritual operating as an agent of cultural change and the rapidity with which such change can occur and can appear to be “old” and “traditional” despite being radically new and can claim to be “Judaism” and not just “women’s customs.”

Creating Successful Ritual

Ritual is repetitive and predictive; much of its power lies in the comfort of being able to turn to it for expression and validation of significant moments. Yet ritual is also innovated constantly, and the challenge is for the new to feel old, natural, “right,” and crucially, efficacious. For all the unabashed innovation of feminist ritual—indeed, because of it—feminists have sought and found precedent for female-specific ritual by women in traditional Jewish societies such as the aforementioned zeved habat birth ceremonies, or Rosh Hodesh, on which women relinquished domestic chores and practiced charitable and ritual activities in each other’s company.

Scholars such as Susan Starr Sered and Chava Weissler have brought to light rich worlds of female spirituality and ritual within traditional Kurdish and Ashkenazi Jewries, respectively. They have shown how traditional women who accepted and indeed venerated rabbinic authority nevertheless authorized themselves to become, in Sered’s words, “ritual experts.” These women sacralized every imaginable aspect of their lives through rituals they created and then successfully communicated as binding for the women of the community—as close an analogue to halakhah (rabbinic law and authority) as one could have.

In the first volume of her Memoirs of a Grandmother, Pauline Wengeroff details a universe of traditional women’s spirituality and ritual, including women prayer leaders (zogerkes) and holy functionaries (gabetes), that operated within, but also parallel to, that of men in the Jewish society of nineteenth-century Russian Poland. In her second volume, she gives a rare portrait of the ritual shearing of the bride’s hair on the morning after the wedding, performed by a gabete, as well as testimony of a mother’s trepidations about the “sacrifice” of her infant son at his ritual circumcision. While feminists reject the gendered hierarchy and marginalization that was the context and site for women’s ritual in traditional Jewish societies, they welcome a “usable past” within Judaism to mitigate the sense of breach with Jewish tradition in feminist Judaism, to validate their own ritual creativity, and to contribute one of the essential elements of successful new ritual: a sense of naturalness, seamlessness, harmony, and continuity.

Feminist Jews have created separate space—literally and figuratively—in which to elaborate, test out, communicate, and establish their creations. But they have also claimed traditional male Jewish ritual space, in synagogues and rabbinical, and cantorial schools. United States feminists were prominent in the creation of the group Women of the Wall in December 1988 (subsequently led by Israelis), who claimed no less than Judaism’s most sacred site, the (women’s section of the) Western Wall in Jerusalem, as a place for women’s group prayer, including Torah reading and the wearing of tallit and tefillin in prayer, and for women’s rituals, such as bat mitzvahs, wedding, and birth celebrations. While until 2013 the group was firmly independent of any established religious movement or denomination and devoted solely to diverse Jewish women’s religious expression and solidarity at the Kotel, it has since split between the “Original Women of the Wall,” who maintain that position, and “Women of the Wall,” who have subsumed the group’s founding issue under the rubric of the struggles of the Reform and Conservative movements for State recognition in Israel.

Jewish feminist rituals reject, create, and also integrate, since the vast majority of Jewish feminists choose to remain within the Jewish community, and in remaining, they profoundly affect all of Judaism. If, in Evan M. Zuesse’s words, rituals “rescue (profane activity) from the terror of inconsequentiality and meaninglessness,” feminist Jewish rituals also rescue feminists from invisibility and derogation in their religious tradition and thus, for all their newness—indeed because of it—are prime agents of continued identification and engagement. They are one of the richest creative streams in contemporary Judaism.

Adelman, Penina V. Miriam’s Well. Rituals for Jewish Women Around the Year. Fresh Meadows, NY: Biblio Press, 1986.

Adler, Rachel. “Tumah and Taharah: Ends and Beginnings.” In The Jewish Woman, New Perspectives, edited by Elizabeth Koltun. New York: Schocken, 1976.

Adler, Rachel. “In Your Blood, Live: Revisions of a Theology of Purity.” Tikkun 8, no. 1 (January/February 1993): 38-41.

Adler, Rachel. Engendering Judaism, An Inclusive Theology and Ethics. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998.

Alexander, Bobby C. “Ceremony.” Encyclopedia of Religion 3:179–183.

Alpert, Rebecca T. “Exploring Jewish Women’s Rituals.” Bridges 2/1 (Spring 1991/5791): 66–80.

Alpert, Rebecca T. Like Bread on the Seder Plate: Jewish Lesbians and the Transformation of Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Balka, Christie, and Andy Rose, eds. Twice Blessed: On Being Lesbians, Gay and Jewish. Boston: Beacon Press, 1989.

Antler, Joyce. Jewish Radical Feminism. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Barack Fishman, Sylvia. A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community. New York: Free Press, 1993.

Berman, Phyllis. “Enter: A Woman.” Menorah 6, 1–2 (November/December 1984).

Berkowitz, Adena K. and Rivka Haut, eds. Shaarei Simcha, Gates of Joy. Jersey City, NJ: Ktav, 2007.

Broner, E.M. A Weave of Women. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1978.

Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. New York: Penguin Books, 1959.

Cantor, Debra, and Rebecca Jacobs. “Brit Banot: Covenant Ceremonies for Daughters.” Kerem (Winter 1992–1993): 45–55.

Chesler, Phyllis and Haut, Rivka, eds. Women of the Wall, Claiming Sacred Ground at Judaism’s Holy Site. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights, 2003.

Cohen, Aryeh. Zeved habat (Hebrew) (1990).

Cohen, Tamara, ed. The Journey Continues: The Ma’yan Passover Haggadah. New York: Ma’yan: The Jewish Women’s Project, 2002.

Coppet, Daniel, ed. Understanding Rituals. London: Routledge, 1992.

De Sola Pool, David, ed. and trans. Book of Prayers According to the Custom of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, 2d ed. (1986.

Diamant, Anita. The New Jewish Wedding. New York: Summit Books, 1985.

Elbaz, Vanessa Paloma, “Kol b’isha Erva: The Silencing of Jewish Women’s Oral Traditions in Morocco.” In Women and Social Change in North Africa: What Counts as Revolutionary?, edited by Doris Gray and Nadia Sonneveld, 263-288.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Falk, Marcia. The Book of Blessings: A Feminist Reconstruction of Prayer. New York: HarperCollins, 1996.

Falk, Marcia. “Notes on Composing New Blessings: Toward a Feminist/Jewish Reconstruction of Prayer.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 3 (Spring 1978): 39–53.

Green, Leona S. The Traditional Egalitarian Passover Haggadah. South Euclid, OH: Norlee Publishers, 2002.

Gross, Rita M. “Female God Language in a Jewish Context,” In Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1979.

Guren Klirs, Tracy, comp. and trans. The Merit of Our Mothers. A Bilingual Anthology of Jewish Women’s Prayers. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1992).

Heschel, Susannah, ed. On Being a Jewish Feminist. New York: Schocken Books, 983.

Hill, Helen. “Simchat Bat…” Jewish Chronicle, August 5, 1994.

Cardoza, Abraham Lopes (former hazzan of Congregation Shearith Israel, Manhattan), and Irma Lopes Cardoza. Interview. January 5, 2004.

JOFA (Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance) Journal.

Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie, and Irena Klepfisz. The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Woman’s Anthology. Montpelier, VT: Sinister Wisdom Books, 1986.

Koltun, Elizabeth, ed. The Jewish Woman: An Anthology. Special Issue of Response, no. 17 (Summer 1973).

Koltun, Elizabeth. The Jewish Woman: New Perspectives. New York: Schocken, 1976.

Leifer, Daniel I. and Leifer, Myra. “On the Birth of a Daughter.” In The Jewish Woman, New Perspectives, ed. by Elizabeth Koltun. New York: Schocken, 1976.

Levine, Elizabeth Resnick, ed. A Ceremonies Sampler: New Rites, Celebrations and Observances of Jewish Women. San Diego, CA: Woman’s Institute for Continuing Jewish Education, 1991.

Lewin, Ellen. “‘Why in the World Would You Want to Do That?’ Claiming Community in Lesbian Commitment Ceremonies.” In Inventing Lesbian Cultures in America, edited by E. Lewin. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Lilith: The Independent Jewish Woman’s Magazine.

Magnus, Shulamit S. “More Light on Menarche.” New Menorah, 2d series, 1 (Winter 1985).

Magnus, Shulamit. “Reinventing Miriam’s Well: Feminist Jewish Ceremonials.” In The Uses of Tradition, edited by Jack Wertheimer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Magnus, Shulamit. “Simchat Lev: Celebrating a Birth.” In Lifecycles: Jewish Women on Life Passages and Personal Milestones, vol. 1, ed. by Debra Orenstein. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 1994.

Magnus, Shulamit. “Kol Isha: Women and Pauline Wengeroff’s Writing of an Age,” Nashim 7 (Spring 2004).

Magnus, Shulamit, ed. Memoirs of a Grandmother: Scenes from the Cultural History of the Jews of Russia in the Nineteenth Century, by Pauline Wengeroff. Vols. 1-2. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010; 2014.

Magnus, Shulamit. A Woman’s Life: Pauline Wengeroff and Memoirs of a Grandmother. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2016./

Magnus, Shulamit. “Thinking Outside the Chains to Free Agunot and End Iggun.” https://blogs.brandeis.edu/freshideasfromhbi/thinking-outside-the-chains-to-free-agunot-and-end-iggun/ and https://blogs.brandeis.edu/freshideasfromhbi/thinking-outside-the-chains-to-free-agunot-and-end-iggun-2/

Myerhoff, Barbara. “Rites of Passage: Process and Paradox.” In Celebration: Studies in Festivity, edited by Victor Turner. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

Myerhoff, Barbara, et al. “Rites of Passage.” Encyclopedia of Religion 12: 380–387.

Ochs, Vanessa. Inventing Jewish Ritual. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2007.

Plaskow, Judith. “God and Feminism.” Menorah 3/2 (February 1982).

Plaskow, Judith. Standing Again at Sinai. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990.

Prell, Riv-Ellen. Interpreting Women's Lives: Personal Narratives and Feminist Theory (with the Personal Narratives Group). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Prell, Riv-Ellen. Fighting to Become Americans: Jews, Gender and the Anxiety of Assimilation. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

Rappaport, R.A. Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

The Reconstructionist: A Journal of Contemporary Jewish Thought and Practice.

Reifman, Toby Fishbein, ed. Blessing the Birth of a Daughter: Jewish Naming Ceremonies for Girls. Englewood, NJ: Ezrat Nashim, 1976.

Response: A Contemporary Jewish Review

Ritualwell.org. www.ritualwell.org

Sered, Susan Starr. Women as Ritual Experts: The Religious Life of Elderly Jewish Women in Jerusalem. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Turner, Kay. “Contemporary Feminist Rituals.” In The Politics of Women’s Spirituality, ed. Charlene Spretnak. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books, 1982.

Turner, Victor. Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977.

Weidman Schneider, Susan. Jewish and Female: Choices and Changes in Our Lives Today. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985.

Weissler, Chava. Voices of the Matriarchs. Listening to the Prayers of Early Modern Jewish Women. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

Weissler, Chava. “Images of the Matriarchs in Yiddish Supplicatory Prayers.” Bulletin of the Center for the Study of World Relations 14, no. 1 (1988): 45–51.

Weissler, Chava. “The Traditional Piety of Ashkenazic Women.” In Jewish Spirituality from the Sixteenth Century Revival to the Present, edited by Arthur Green, 245-275. Vol. 2. New York: Crossroad Publishing, 1987.

Weissler, Chava. “Traditional Yiddish Literature: A Source for the Study of Women’s Religious Lives.” The Jacob Pat Memorial Lecture, Harvard College Library, 1987.

Yoreh, Tzemah. “Reciprocal Oaths: A New Model for Jewish Marriage,” Jewish Law Journal, 2019 (forthcoming)

Zuesse, Evan M. “Ritual.” The Encyclopedia of Religion. Detroit, MI: Thomson/Gale, 1987.