Politics in the Yishuv and Israel

Between 1917 and 1926, the struggle for women’s suffrage was one of the main concerns in the nation-building process of the Jewish community in Palestine. Following the achievement of suffrage, many barriers to women’s equal political citizenship remained. After 1948, women seemed to be included as legitimate and valuable political actors, but the next two decades saw a retreat of women from the political sphere and a marked regression in gender equality. Following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the gendered role division reached such an unprecedented level that it could no longer be ignored, and feminist voices gradually became involved in academic and political discourse. New women MKs moved from tackling remaining bastions of inequality in the military and the religious domain to more activist legislation. The early twenty-first century saw an increase in women’s political participation but also a backlash against Israeli women and efforts to promote their human rights.

It is in the politics of equality that new social imaginaries are forged, not in the unfolding of an inherently “modern” ideal.

Anne Philipps, 2018:837

Introduction

Women have often striven to be fully included in today’s world, as have other social categories left out of modernity's claim for freedom and equality, such as slaves, workers, persons with disabilities, poor people, and LGTBQ+ individuals. The political arena has been one of the main platforms feminists have used to promote their basic human rights and achieve equal citizenship, be it legal, political, or social.

In that spirit, feminists have adopted two main strategies, both of which remain pivotal today. The first strategy, which initially focused mainly on the struggle for women’s suffrage, now aims to increase both women’s descriptive representation (i.e., the percentage of women in political centers of power, elected at the local, regional, and national levels) and their substantive representation (i.e., the inclusion of women’s human rights at these loci of power). The second strategy involves the politicization of women’s basic human rights—that is, women’s right to liberty, property, and safety and to resist oppression—by exposing “to conscious awareness the political nature of existing social arrangements” (Boals, 1975, 173) and by bringing individuals or specific issues into the arena of conventional electoral and governmental politics (Jajawardena 1986; Pateman 1988; Lovenduski and Norris 19996; Fogiel Bijaoui 2011; Philipps 2018; Franceschet et al. 2019; Paxton and Hughes 2021).

Israel is no exception to these trends. Institutionalized politics and a variety of factors—the politicization of women’s issues, the Israeli-Arab conflict, the impact of religion on the political arena, and the socio-economic structure—have resulted in both exclusion and inclusion of women in Israeli politics. The following sections present a contextualized, socio-historical overview of women and politics in the Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv and Israel in four periods:

- The Formative Years: 1917-1948

- The Politics of Patriarchy: 1948-1970

- The Feminist Era: 1970-2001

- Feminist Politics and Populism: 2000-2021

The Formative Years: 1917-1948

After the Balfour Declaration in 1917, the political system of the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine was based on what were then perceived as democratic procedures of representation to the elected bodies: the Asefat ha-Nivharim (the elected assembly, forerunner of the Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset) and the Vaad Leumi (the national committee, the governing body of the community, chosen by the elected assembly). Although the universal, proportional, list-based electoral method was adopted, women’s suffrage was not originally part of this social contract. On the contrary: from 1917 to 1926, the struggle for women’s right to vote was one of the main concerns in the nation-building process of the Jewish community in Palestine.

In those years, the suffrage struggle was conducted by the Union of Hebrew Women for Equal Rights in Eretz Israel (Ithachdut Nashim Ivriot Le Shivyon Zkuyot in Eretz Yisrael), led by Sara Azaryahu, together with other organizations such as the Hebrew Women’s Organization (Histadrut Nashim Ivriot Le Shivyon Zkuyot in Eretz Israel) and Hadassah, organizations that were part of the Center and Liberal Right (Hugim Ezrahim). The Women’s Workers’ Movement [Tnuat Hapoalot] played a secondary role but was also an important political actor in women's struggle for equal political citizenship.

In that struggle, the feminists were supported by the Liberal Right and the Labor Movement, which was becoming the dominant force in the Yishuv. However, their opponents—the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) sector, the Religious-Zionists (Mizrahi), the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardi sector, and the private farming sector—had an important asset. Fiercely opposed to women’s suffrage, which they saw as immoral and anti-religious, they threatened to boycott the elected bodies of the Jewish community. In the early 1920s, the ultra-Orthodox and their allies constituted nearly half the Jewish community in Palestine, and such a boycott might have led to the delegitimization of the elected bodies of the Yishuv as its representatives to the British authorities and to the negation of those bodies’ authority over the Yishuv itself. The threat was so real that, more than once, even the “women’s allies” were prepared to sacrifice women’s political rights.

In the end, the struggle for women’s suffrage was a real feminist and democratic victory, based on the politicization of women’s rights as part of the national struggle, women’s cooperation, and their organizational capability. First, women became entitled to vote and to run for office. In the first Asefat ha-Nivharim, in 1920, 4.5% of 314 elected delegates were women; in the second Asefat ha-Nivharim, in 1925, 25 women were elected, or 11.5 % of the 221 delegates; in 1931, women constituted 8.5% of the 71 elected members; and finally, in 1944, among the 171 delegates at the fourth Asefat ha-Nivharim, 25, or 15%, were women. Women also became part of the Vaad Leumi, the executive branch of the Yishuv’s quasi-national institutions, where their representation was proportional to their achievements in the Asefat ha-Nivharim. Thus, one woman was part of the Vaad Leumi under the first Asefat ha-Nivharim, four under the second, one under the third, and four under the fourth.

There were also real achievements in the realm of substantive representation. Most of the women elected were feminists, whether liberal or socialist, as were the women serving in the Vaad Leumi, such as Sara Azaryahu, Yochevet Bat-Rachel, Ada Fishman-Maimon, Rachel Cohen-Kagan, Henrietta Szold, Rahel Yanait Ben-Zvi, and Esther Yavin. Moreover, on the legal level, at the end of the second session of the Asefat ha-Nivharim on January 15, 1926, an official declaration confirmed equal rights for women in all aspects of life in the Yishuv, civil, political, and economic. This declaration was further ratified by the Mandate government in 1927 and became one of the cornerstones of Israel democracy.

A variety of feminist frameworks were also created, including feminist organizations; women’s parties, which represented women’s rights and pressured other parties to enlarge the proportion of women on their lists; and a feminist press for advancing women’s rights. These and other frameworks later became assets for Israeli feminists in promoting a politics of equality.

Despite these achievements, however, the feminist victory was limited. In the short run, women had to go through additional struggles to gain suffrage in the towns and moshavot (private agricultural farms). Although women in Tel-Aviv and Haifa could already vote at the local level, in Jerusalem women could vote only from 1932 on and in Petah Tikvah only beginning in 1940. By 1948, women in all Jewish localities had won the right to vote and seek office. As for the politics of equality, after the suffrage achievement, cooperation between the Liberal and Socialist feminists practically came to an end in the second half of the1920s, despite the fact that it had been one of their sources of power; this development significantly weakened the women’s movement.

In the long run, many barriers to women’s equal political citizenship remained, including the “self-understood” exclusion of Arab-Palestinian women. Shaped by both Zionism and feminism, the suffrage movement played a key role in constructing the new Jewish collective identity, based on modernism, nationalism, and democracy. Jewish feminists seized upon nationalism to construct women’s equal political citizenship, and Jewish nationalism seized upon women’s citizenship to advance the national enterprise. This left no place for another national entity, specifically for the Arab-Palestinian feminists, who, from the 1920s on, established an organized movement actively involved in social, political, and national affairs. In the following decades, these seeds of disunity plagued feminist politics in Israel, even at the grassroots level.

Moreover, for what they characterized as moral and religious reasons, many parties chose to deny women political citizenship, even though the Zionist-Religious sector and the Revisionist party (far Right) began in 1925 to include women as delegates to the Yishuv institutions. In addition, the achievement of suffrage did not change the ethnic gap between Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi and Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi women and their power relations. On the contrary, it reflected the hegemony of the former over the latter, and this hierarchy remained a central characteristic of the feminist landscape for several decades.

Broadly speaking, in the formative years, women’s victory on suffrage played a significant role in the establishment of democratic norms and practices in the Yishuv, such as women’s descriptive and substantive representation in elected bodies and the legal definition of women’s rights as universal human rights. On the other hand, on the eve of independence, most of the mechanisms of exclusion of women from the Israeli political sphere were already in place (Gorny 1970; Izraeli 1981; Bernstein 1987, 1992; Fogiel-Bijaoui 1992; Herzog 1992; Safran 2001; Hertzog 2002; Fleischman 2003; Shilo 2016).

The Politics of Patriarchy: 1948-1970

According to Itzkovitch-Malka and Friedberg, “When the [Israeli] State was established in 1948, women’s political equality was already a given and indeed there was no dispute on women’s right to vote and to run for office. This time, due to the War of Independence and the fact that women’s suffrage was already a given fact for more than twenty years, the ultra-Orthodox sector decided not to segregate itself and joined the representative institutions of the State of Israel” (2019, 533). Thus, with statehood, women seemed to have been included as legitimate and valuable actors in the political sphere. During the Provisional State Council (Moezet Ha-Medina Ha-Zmanit), which lasted from May 14, 1948, until the seating of the first Knesset on February 2, 1949, three National Councils were elected, with five women serving in each one. Two women were signatories of the Israeli Declaration of Independence: Golda Meir, representative of Labor (Mapai), who was appointed Minister of Labor in 1949, after the formation of the first government, and Rachel Cohen-Kagan, representative of the Women’s Party-WIZO, the party composed of the Union of Hebrew Women for Equal Rights in Eretz Israel and the Union of Zionist Women (Hisradrut Nashim Tzioniot, which resulted from the 1933 merger between WIZO-Israel and the Hebrew Women’s Organization). The Declaration of Independence itself confirmed the state’s commitment to banning sexual discrimination in the social and political sphere (although not in the family sphere) and was one of the earliest legal documents to include equal rights for women as a principle applying to a large spectrum of civil rights and legal competences the state granted its citizens.

Moreover, two women’s parties participated in the 1949 elections: the Women’s Party-WIZO and the Zionist-Religious women’s party (the PD list), which received thousands of votes even if it did not pass the threshold necessary to enter the Knesset. (The PD list, an audacious and courageous innovation, was founded by religious women who seceded from the Zionist-Religious parties in protest against the alliance with the Haredi parties and the formation of the United Religious Front, which did not allow women on its candidate lists.) A decade after the foundation of the state, Israel ranked very high in the world in terms of its descriptive representation of women. At the time of the Third Knesset (August 15, 1955 – November 30, 1959), for example, 10% of all Knesset members were women (twelve out of 120 MKs; see Table 1), then a world record. Last but certainly not least, Golda Meir served several times as minister at a time when few women held that position: labor minister, foreign affairs, minister of interior. Moreover, in 1969, she was among the first women in the world to become prime minister.

However, a closer examination of the first two decades of statehood [First Knesset, 1949-1951, through Seventh Knesset, 1969-1973] reveals another story, that of a retreat of women from the political sphere together with a marked regression in gender equality. Women’s descriptive representation diminished throughout the 1960s, and in the election to the Seventh Knesset in 1969, only eight women (7% of the MKs) were elected. Moreover, in these years, Israel was left behind, comparatively speaking, as the representation of women in the Israeli Parliament did not continue to rise as it did in other countries. Likewise, the Zionist-Religious women’s party (the PD list) disappeared shortly after the 1949 elections, and women’s exclusion from the Haredi parties continues today. During the early decades of statehood, only one woman served in each government: Golda Meir, who served, as minister of Labor, minister of Interior, minister of Foreign Affairs, and as prime minister, as noted above.

At the local level, the situation regarding the descriptive representation of women was even worse from the very start: In 1950, only 4.2% of those elected at the local level (municipalities and local councils, or Moatzot Mekomiot) were women, and in 1965 women accounted for only 3.1% of elected representatives (see Table 2). Moreover, at that time, very few Israeli-Palestinian women held office at the local level.

| Election Year * | Percentage of Women Elected ** |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 4.2 |

| 1955 | 4.1 |

| 1959 | 3.6 |

| 1965 | 3.1 |

| 1969 | 3.6 |

Table 2: Women's Representation at the Local Level in Israel. Sources: Herzog 1994; Akirav & Ben-Horin 2016; Avgar 2019; Akirav 2021.

*Regional Councils not included.

**Until 2008, the figures do not include the Israeli-Palestinian Councils. For instance, in 1998, 0.4% of the Israeli-Palestinians elected at the local level were women. So, the percentage of all Israeli women at the local Councils was actually 10.2% and not 14.9%, as reported. In other words, the percentage of women elected at the local level before 2008 are much lower. From 2008 on, Israeli-Palestinian women, elected at the local level, are included in the figures presented here.

This gradual exclusion of women from the public sphere reflected the priorities of the state’s first two decades, which were largely incongruent with the vision of a democratic state and a commitment to gender equality. At that time, Israel’s priorities were its physical survival, the integration of immigrants, economic development, and the relationship between religion and the state. These priorities explain, at least in part, the glorification of the military; the military government imposed on Israeli Palestinians, seen as a disloyal “fifth column”; the imposition of “Western education” on Mizrahi children; the austerity programs imposed by the government; and the institutionalization of a religious monopoly over burial, marriage, and divorce.

In these two decades, women politicians did not completely disregard the complex contents of substantive representation. Among the female MKs were ardent feminists like Rachel Cohen-Kagan (WIZO and later Liberal Party) and Ada Fishman-Maimon (Mapai), whose feminist voice was still vibrant in the Israeli Parliament. In 1951, Cohen-Kagan initiated deliberation on the Law of Family and the Equality of Women, a very detailed bill dealing with the broad issues of gender equality in society and in the family. On the basis of that proposal, the Knesset ratified a Law of Equality for Women (1951), which granted married women full competence in handling property and custody of their children and annulled discriminatory provisions of the Succession Act but also maintained religious jurisdiction over matters of marriage and divorce. (Not surprisingly, Cohen-Kagan abstained from voting for the law she initiated.) Likewise, Maimon succeeded in proposing and passing a law setting the minimum age of marriage for women at seventeen (Minimum Marriage Age Law, 1950). Even Golda Meir, who had serious reservations about feminism, secured maternity leave for Israeli women (Women’s Employment Law, 1954).

However, in light of state priorities, women politicians and women’s organizations (generally associated with political parties) saw their main contributions to the nation-building process as supporting women as wives and mothers, thus becoming complicit in entrenching gender boundaries. The fact that their personal status and/or the status of their organizations was dependent on party machineries only reinforced the political credo that women’s first national mission was to create the modern (Jewish) labor and military force needed to consolidate the new state’s existence. Women's integration into the labor market dropped, while the representation of Mizrahi women in undervalued and underpaid sectors increased. In the A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim, women became nearly completely concentrated in the services, rather than in the “productive works,” which led to the top functions in the community, while in the IDF, women—“potential mothers”—were formally excluded from combat roles and given mostly clerical and social service duties.

This approach no doubt contributed greatly to the legitimation of women’s exclusion from the political space and was pivotal in creating and fueling social hierarchies between groups of women, especially between Ashkenazi women (constructed as “modern”), Mizrahi women (constructed as “modernizing”), and Palestinian women (constructed as “traditional”), while any critical discourse on the political status of Haredi women, excluded from the right to be elected to national institutions, was silenced. Thus, though epitomized by the mythical figures of Golda Meir, kibbutz women, and female soldiers, the first two decades of Israeli statehood were in fact the most problematic years for Israeli women, and the lowest point in the history of Israeli feminism (Yuval-Davis 1980; Izraeli 1981, 1997; Radai 1982; Bernstein 1983; Fogiel-Bijaoui 1992, 2011; Berkovitch 1997; Herzog1998a, 1998b, 1998c 2002; Triger 2014; Chazan 2018; Stern 2018; Itzkovitch-Malka and Friedberg 2019; Rosenberg-Friedman 2019; Avgar and Fiedelman 2020; Geva 2020).

The Feminist Era: 1970-2001

From the perspective of gender equality politics, the beginning of the new period that began in the 1970s was not promising. After the Six-Day War (1967), Israel was preoccupied with the question of borders and territories and the army was the fulcrum of the social ethos, with an emphasis on men and masculinity as the ultimate model of the “civilian” who contributes to the life of the community. The Yom Kippur War (1973) then changed the course of the state’s history. One of the first reactions of the new national mood after the war was the emergence of virulent protest movements demanding total change in the system, from which they expressed growing alienation. Some of these protest movements, such as the Black Panthers, had already been active before the war, while others—such as demobilized reservists, Zionist-Religious activists, pro-peace militants, and Palestinian Israelis (finally freed in 1966 from military government)—emerged after the war. This general unrest put an end to the basic myths and creeds that had legitimated the social order and the hegemony of the Labor Movement, leading to the rise, in 1977, of the Right and its dominant party, Likud.

In this iconoclastic atmosphere, one of the debunked myths was that of gender equality. Israelis had been convinced that their society enjoyed gender equality, in both the pre- and post-state periods, and thus that no equality politics was needed. Therefore, women, as a group, had not considered the system as discriminating against them, did not believe they had a different political agenda, or did not develop political behavior patterns that differed from men’s. Thus, for women, the Yom Kippur War served as a kind of mirror that reflected with painful clarity Israel’s social structure and their place within it.

Although many women’s feelings of anger and frustration were soon channeled into activities considered “proper,” such as support for soldiers, the wounded, widows, and orphans, from a feminist standpoint the gendered role division had reached such an unprecedented level during the Yom Kippur War that it could no longer be ignored. Feminist voices gradually became involved in academic and political discourse. This was not entirely new: in the 1960s, some feminist voices had sporadically been heard in the public sphere (such as in relation to the 1964 Male and Female Workers Equal Pay Act), while feminism’s Second Wave had been launched in 1970 by two faculty members at the University of Haifa, philosopher Marcia Freedman and psychologist Marilyn Safir, both originally from the United States (as were many others among the “founding mothers” of the Second Wave in Israel). In that year, Freedman and Safir held a feminist seminar at Haifa University, engendering a radical discourse critical of the “gender equality myth” and of the degree to which women were politically suppressed in Israel’s male-dominated society. The war, then, not only channeled women to their “proper” roles; it also pushed some women (and men) to hold publicly a critical feminist approach to the gender order, thus strengthening the nascent feminist movement.

In 1975, the UN International Year of the Woman, this trend was further reinforced when a commission, headed by Ora Namir (Labor), was appointed to examine the status of women in Israel. The commission’s report, submitted in 1978, examined the place of women under the law and in education, the military, the labor market, the family, and decision-making centers, and investigated the plight of women in distress. The findings revealed for the first time the scale of systematic gender inequality in society and were an eye-opener for many women (and men). The Commission on Women’s Status also created the position of Advisor to the Prime Minister on the Status of Women and gave women from different spheres the opportunity to work together, a formative experience for a new generation of feminist academic and political leadership.

In the following two decades, feminist organizing from bottom up intensified, fueled by a substantial rise in the number of women in the labor force and in higher education (although this rise hardly translated into equality in income or status). This organizing was characterized by consciousness-raising, grassroots initiatives, and the absence of direct dependence on political parties, which allowed for the emergence of feminist peace activism (for instance, Women in Black, established in 1988). Many organizations highlighted a single issue, such as violence against women, rape, the plight of Woman who cannot remarry, either because her husband cannot or will not give her a divorce (get) or because, in his absence, it is unknown whether he is still alive.agunot, or offensive advertising; these issues were echoed in the Hebrew-language feminist journal NOGA, published in Israel from 1980 to 2005.

Although most of these organizations were small and marginal, the merging of the different voices changed the public climate on the issue of women’s status. Alongside the radical feminist organizations, the Israel Women’s Network, headed by Alice Shalvi, was established in 1984, defining its main mission as advocacy work with Knesset members, decision-makers, and policy-setters. The Network was yet another innovation in the community of women’s organizations in Israel. Most of its founders came from academia; their entry into feminist activities constituted more than crossing the line separating the academy from politics, for these women eventually opened gender and women’s studies tracks in Israel’s universities and colleges, thereby helping to expose the gendered-political aspects of society and of academic discourse.

Finally, under the influence of feminist civil society and gender and women's studies programs, institutionalized organizations began to see the concept “feminism” as less threatening. Increasingly, Na’amat (the name of Moetzet Hapoalot beginning in 1976), WIZO, and even Emunah (the name of the Zionist-Religious women’s organization beginning in 1977) embarked on consciously feminist activities, through training, journalism, and political efforts. They also displayed greater willingness than before to collaborate with other organizations on specific issues, such as those relating to women’s status in the rabbinical courts or violence against women.

At first sight, this feminist activism was only partially translated into the political arena. Ratz, the Citizens’ Rights Movement, the first party in Israel to be formed by a woman, well-known feminist Shulamit Aloni, won only three seats in the elections to the eighth Knesset in December 1973. Moreover, although two women’s parties were founded, they did not pass the qualifying threshold to enter the Knesset. The first was the 1977 women’s list, supported by Marcia Freedman and headed by Shoshana Ellings; the second, in 1992, headed by Ruth Reznik and Esther Herzog, did not cross the qualifying threshold, which at the time was only 1%.

The relatively low impact of feminist activism on the political arena also appears in the constant but very moderate rise in women’s representation in local politics (Table 2), even though the electoral method was changed in 1978 and for the first time voters could vote directly and separately for the mayor and for a party list for seats on the city or local council. To be sure, in the 1980s and 1990s, more women began to run for elections as heads of a list and of local authorities—and some were elected. The 1998 local elections achieved breakthrough results when, for the first time, women became mayors of two mid-size towns (not small-size municipalities): feminist Yael German from Meretz in Herzliya and Likud representative Myriam Feierberg in Netanya. Without doubt, public norms and attitudes and the image of women politicians were changing, and the Israeli public was more willing to see women politicians serving on local councils and as mayors. Nevertheless, in 1998 women represented only 10.9% of those locally elected (0.4% among Israeli-Palestinians and 14.9% among the Jewish population).

The representation of women in the Knesset and the government was no better. In the Knesset, the percentage of women members from 1973 to 1999 was between 6 % and 9%. Only in the 1999 elections (15th Knesset) did the percentage rise to 12% (Table 1). In the 1980s, the Israeli cabinet included either one woman minister or none at all. Not until 1992, during the second Rabin government, were two women included in the Cabinet; two were also included in 1999-2001, in the government of Ehud Barak (Table 3).

| Name & Party | Portfolio | Dates in Office |

|---|---|---|

| Shulamit Aloni - Labor, Ratz, Meretz | Without Portfolio; Education & Culture; Communications; Arts & Sciences | 1974; 1992-1993; 1993-1996 |

| Sarah Doron - Likud | Without Portfolio; Education & Culture; Communications; Arts & Sciences | 1983-1984 |

| Shoshana Arbeli-Almozlino - Labor-Alighment | Health | 1986-1988 |

| Ora Namir - Labor-Alignment | Environment; Labor & Welfare | 1992; 1992-1996 |

| Limor Livnat - Likud | Communications; Education; Culture & Sport | 1996-1999; 2001-2006; 2009-2015 |

Table 3: Women Government Ministers in Israel, 1974-2001.

Though the growth of women’s consciousness—reflected at the grass-roots level and in the activities of women’s organizations—was only partially echoed in the numbers of women elected, significant feminist change did occur, reflected in the agenda of the Knesset. New women MKs were almost all feminists who came with experience in the Israel Women’s Network or related feminist activities. These women viewed themselves as representing women’s rights with a definite feminist agenda and set out to systematically rewrite gender-based laws. They moved from tackling remaining bastions of inequality in the military (with the removal of impediments to female service in combat units and the dismantling of the separate women's branch of the IDF) and, less successfully, in the religious domain, to more activist legislation on affirmative action, violence against women, sexual harassment, benefits for working women, single-parent families, gay rights, and laws designed to promote the needs of specific groups of women. In 1999, Hussniya Jabara, a feminist activist at Naamat, was the first (Muslim) Israeli-Palestinian woman to become a MK on the ticket of Meretz (formerly Ratz) and was active in promoting women’s rights, especially Israeli-Palestinian women’s rights

The campaign for women's rights also took on institutionalized forms. In 1978, as described above, the first advisor on the status of women was appointed in the Prime Minister's Office. In the 1990s this trend of “state-feminism” was strengthened: In 1992, the Knesset created what became a standing Committee on the Status of Women and Gender Equality (formerly the Committee on the Advancement of the Status of Women). In 1998, the National Authority for the Advancement of Women was established. In 2000, advisors on women's affairs were mandated in all local authorities. The Committee on the Advancement of the Status of Women deserves special attention; among other achievements, it successfully introduced a broad range of feminist issues to the Knesset and the general public, allowing women's and especially feminist voices and concerns to be heard. This was very important because a significant part of the Knesset’s work is carried out by committees, and, as seen in Table 4, from the 8th to the 15th Knesset (1973-2001), women were absent or underrepresented in parliamentary committes, even in the “feminine” Education and Culture Committee.

| Knesset | Finance Committee | Foreign Affairs and Defense | Labor, Welfare, and Health | Education and Culture | Advancement of the Status of Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Women | % of Women | No. of Women | % of Women | No. of Women | % of Women | No. of Women | % of Women | No. of Women | % of Women | |

| 1 | 1 | 6.5 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 33 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 20 | 5 | 33 | ||||

| 3 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 46 | ||||||

| 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 16 | 3 | 16 | ||||

Table 4: Membership of Women MKs on Specific Parliamentary Committees, 1949-2001. Source: Golan & Hermann, 2005.

On the whole, feminism in this era did create cultural change and improve Israeli women’s social status, but it remained a rather weak actor in formal politics, for three main reasons: First, feminists became more and more divided. It increasingly appeared that categorizing women as a collective ignored striking discrepancies among groups of women, at the center and the periphery. Feminist leaders, mostly highly educated middle-class women of Ashkenazi descent, with an over-representation of Anglophone women, were not always sensitive to the situation of low-income, Mizrahi, Palestinian, religious, migrant, disabled, and lesbian women, preventing the formation of a uniform feminist identity that could unite women and crystallize into a single political force. Feminists also found it virtually impossible to penetrate the male bastion constructed around the dominant issues of security and peace matters, thus explaining the rise of feminist peace organizations such as Women in Black, the Four Mothers’ Movement, Bat Shalom/the Jerusalem Link, and a myriad of local initiatives and helping to account for feminist women’s absence from central policy-making positions. Finally, the exceptional centrality of religion in codifying the social and political order served as a barrier to feminist political power. In Israel, religion, a determinant patriarchal force, is “nationalized,” for it is seen as preserving the collective identities of the competing ethno-religious groups in Israel’s population and controlling the symbolic and legal boundaries of the national collectives, especially those between Jews and Israeli-Palestinians and those between the different Israeli-Palestinian communities, such as Muslim, Christian, and Druze Arabs (Hazelton 1977; Yuval -Davis 1980; Radai 1982; Raday, Shalev and Liban-Kooby 1995; Bernstein 1983; Herzog 1987, 1996, 1998a, 1998b, 1998c; Sharfman 1994; Friedman 1990; Svirski and Safir 1991; Fogiel Bijaoui 1992, 1992 b, 2011; Friedman 1995; Herzog 1996, 2000, 2001, 2006; Azmon 1997; Berkovitch 1997; Hasan 1997; Izraeli 1997; Abu-Baker 1998; Helman and Rappaport 1997; Izraeli 1999; Naveh 1999; Lemish and Barzel 2000; Safran 2001; Benski 2007; Golan and Hermann 2005; Akirav and Ben-Horin 2016; Chazan 2018; Avgar and Fiedelman 2020, 2021; Safir 2021).

Feminist Politics and Populism: 2000-2021

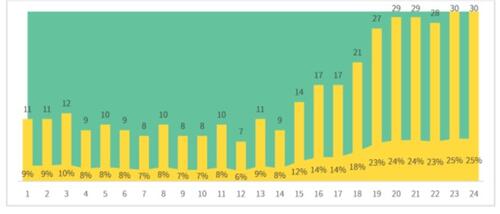

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, paralleling the growing importance of populism in public and political discourse, women’s political vulnerability and feminist political weakness increased, especially in the last part of this period. On the surface, the two decades were marked by a remarkable increase in women's participation in the political arena. From the 16th Knesset (2003) to the 23rd Knesset (2020), women jumped from 14% to 25% of those elected (Table1). Moreover, women MKs became more diverse, so that in the 23rd Knesset different societal groups of women were represented, including Arab-Palestinians, ultra–Orthodox women (elected in a secular party), “newcomers” from the Former Soviet Union, and Ethiopian and disabled women.

The number of women in ministerial positions also rose gradually. Through the 34th government (2015-2020), the percentage of women ministers ranged from none to four women, but the number jumped to eight during the 35th government (2020). However, because this was the largest government ever formed in Israel, women constituted only 23.5% of members (Table 5) holding portfolios considered less “prestigious" (Ministries of Environmental Protection, Immigrant Absorption, Education, and Communications) (Table 6).

| Government | Number of Women in the Govrnment | Percentage of Women in the Government |

|---|---|---|

| Sharon - 2003 | 3 | 13 |

| Olmert - 2006 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Netanyahu - 2009 | 2 | 6.7 |

| Netanyahu - 2013 | 4 | 18.2 |

| Netanyahu - 2015 | 3 | 14.3 |

Table 5: Women's descriptive representation in the Israeli Government, 2003-2021. Source: Konig 2020, 2021.

| Name & Party | Portfolio | Dates in Office |

|---|---|---|

| Tzipi Livni - Likud, Kadima, Kadima, Hatumah | Regional Cooperation, Without Portfolio, Agriculture, Housing & Construction, Immigrant Absorption, Justice, Foreign Affairs, Vice Prime Minister | 2001-2009; 2013-2014 |

| Yehudit Naot - Shinui | Environment | 2003-2004 |

| Ruhama Abraham - Likud, Kadima | Without Portfolio, Tourism | 2007-2009 |

| Sofa Landver - Yisrael Beitenu | Immigrant Absorption, Aliya & Integration | 2013-2015; 2016-2018 |

| Orit Noked - Independence | Agriculture & Rural Development | 2011-2013 |

Table 6: Women Government Ministers, 2001-2021.

A gradual rise also occurred at the local level, among both the Jewish and Arab communities (Table 2). In 2018, 16.2% of all councilmembers elected were women (0% in the ultra-Orthodox sector, 2% in the Arab sector, and 25% in the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish sector), an overall increase of nearly 3 percentage points from the 2013 elections (13.5%). In part, this increase may be related to Amendment No. 12 of the Local Authorities (Elections Financing) Law-1993, passed in 2014 to increase women's representation in local politics by offering an economic incentive for placing women in realistic positions on party lists in cities and local authorities. The amendment dictates that increased election funding (15% of the total election funding) will be given to any party in a local council made up of at least one-third women. The 2018 elections marked the first time this amendment was in effect.

As for the substantive representation of women at the local level, female councilmembers acknowledge the importance of gender awareness and gender mainstreaming, in both "women's issues" such as education and community and "men's issues" such as housing, finances, and security (Akirav 2021). They regard them as part of their mission, together with empowering women to participate in politics.

Until the 2009 elections in Israel, researchers and political pundits assumed that there were no significant differences between the voting patterns of women and men. However, research conducted by Einat Gedalya-Lavy, Hanna Herzog, and Michal Shamir on the 2009 Knesset election revealed a “modern gender gap” (in which more women vote for center-left parties and more men for right-wing parties): 28% of Jewish women and 21% of Jewish men voted for the center party Kadima, led by the female politician Tzipi Livni, who faced Benjamin Netanyahu and his Likud party. In the same year, Arab women also voted more than men for Balad, an Arab party with a woman candidate, Haneen Zoabi, who was elected to the Knesset. This was the first time an Arab woman was elected on an Arab Party list, and not on a Zionist party list (like Hussniya Jabara and Nadia Hilu before her). This gender gap reappeared in the following elections, indicating that women could become a political force.

However, the jump in descriptive representation and the changes in women's political participation were not translated into substantive terms and did not transform the gender order. The result was a backlash at the end of this period against Israeli women and efforts to promote their human rights—a backlash reinforced by the Covid-19 crisis.

To be sure, there were some achievements, especially in the first decade, such as the ratification in 2005 by Israel—the first country to adopt legislation on the subject—of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000), which states that UN member states should act to ensure equal participation of women in all decision-making, protect women from violence, and conduct gender assessment of diverse groups of women to prevent violence and promote peace. Achievements also occurred in employment, health, and social benefits, mostly minor additions to existing laws. But the dominant trend was a gender-regressive scenario, with formal and informal policies, practices, and procedures that reinforced gender-based stereotypes and gender inequalities. This process was flagrant regarding women’s presence in the public sphere. Indeed, for the first time since the establishment of the state, gender segregation in higher education was accepted, progress on gender equality in the IDF was impeded to placate religious sensitivities, increasing numbers of Israeli women singers were silenced on public radio, more women were excluded from public events, and the drive for pluralist prayers in holy sites—spearheaded by Women of the Wall—was stymied.

With increased educational attainment, women continued to enter the workforce, almost equaling the percentage of men. However, many women found themselves in insecure, less remunerative fields and often in part-time positions. Moreover, between 2008 and 2018, the gender pay gap remained essentially stable; in 2008, women earned 82.7 % of what men earned, and in 2018, 84%. Against this background, with the Covid crisis, when parents—mostly mothers—had to stay home to take care of their children, unemployment increased, especially for women.

The extent of various forms of intimate partner violence perpetrated by men against women also did not diminish in the first decades of the twenty-first century, and it even grew during the Covid crisis. Divorce procedures became harder for Israeli women, who, in any case cannot divorce without their husbands’ consent; due in part to successful lobbying of antifeminist men’s groups, Family Courts and abuse professionals became polarized over the use of “parental alienation” claims to discredit mothers and increase their risk of losing custody.

Despite the increase in women’s descriptive representation, Israel still lagged other countries. For instance, in the EU in 2017, 14.9% of heads of local councils were women (compared to 5.5% in Israel following the 2018 elections); in the councils themselves, women constituted close to 32.1% of members (compared to 16.2 % in Israel). The percentage of local councils headed by women in the EU was thus almost three times higher than in Israel, and the percentage of women councilmembers almost double. As for women in the Knesset, during these two decades Israel dropped from 46th place in 2001 (15th Knesset) to 54th place in 2019 (20th Knesset) on the IPU Women in National Parliaments Ranking, even though the percentage of women in the Knesset greatly increased.

This general downturn of gender equality politics had more than one cause. One factor was certainly the protracted Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with its peaks of violence (Second Intifada, Second Israel-Lebanon War, Gaza Wars), which put security issues at the top of national priorities and minimized the legitimacy of “specific” (i.e. women’s) demands. Another was the growing influence of religion in the political arena and the strengthening of ultra-Orthodox and Islamist parties, with no women representatives in their elected bodies and virulent patriarchal discourse and practices (although a woman, Iman Khatib-Yasin, was elected for the first time on an Islamist party list to the 23rd Knesset, 2020-2021).

However, the growing influence of right-wing populism in Israeli politics under the leadership of Prime Minister Netanyahu also cannot be underestimated. Right Populism—opposing “the elite,” defending “the common people,” and proclaiming “popular sovereignty” as the only legitimate source of political power—is based on a politics of fear, inspired by a traditionalist nativist rhetoric of exclusion that opposes “us” to “them.” As such, it has the political impact of curtailing the space for debating progressive gender discourse and gender equality politics. With the prioritization of electoral success over women’s substantive representation, women MKs and ministers on the right of the political spectrum promoted, especially from the 2010s on, only gender issues that seemed “appropriate” to the Right Populist agenda and ipso facto fueled the backlash against women and feminism.

Although new frameworks such as Women Wage Peace (formed shortly after the 2014 Gaza War) existed, feminists were limited in their capacity to grapple with these trends, which were also accompanied by the intensification of socio-economic and cultural neoliberalism. On the one hand, the gendered character of the new socioeconomic policies led many of the veteran women's organizations, such as WIZO, Emunah, and Na'amat, as well as the Israel Women's Network and several professional women's rights associations, to apply their impressive skills to either providing vital services with fewer resources or promoting egalitarian goals on noncontentious matters. This process of "NGOization," however, curtailed their capacity to mobilize broad constituencies and hence to affect policies, while key women's action was essentially de-politicized. On the other hand, with a multicultural approach, anchored in identity politics, feminist grass-roots organizations were unable to elaborate a common political agenda that could mobilize women and crystallize into a political force (Herzog 1999, 2000, 2001; Sasson-Levy 2006; Halperin-Kaddari and Yadgar 2010; Fogiel-Bijaoui 2011, 2016; Wodak 2015; Akirav and Ben-Horin 2016; Gedalya-Lavi 2016; Hacker 2016; Lachover 2017; Chazan 2018; Philipps 2018; Shapira and Konig 2018; Avgar 2019; Franceschet, Krook, and Tan 2019; Harel-Shalev, and Daphna-Tekoah 2019; Itzkovitch-Malka and Friedberg 2019; Radai 2019; Avgar, and Fiedelman 2020, 2021; Kantola, and Lombardo 2020; Konig 2020, 2021; Shamir, Herzog, and Chazan 2020; Tzameret et al. 2020; Akirav 2021; Paxton and Hugues 2021).

Conclusion

The April 2021 elections to the 24th Knesset and the formation of the Bennet-Lapid government may well represent a turning point. A breakthrough occurred when Orna Barbivai became the first woman to head the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, one of the most desirable positions in Israel's male-dominated security establishment. The "modern gender gap" referred to above may at least partly explains the revival of the Labor party, headed by Merav Michaeli, a feminist avant-garde figure. Moreover, diverse groups of women are represented at the Knesset. This now includes Iman Khatib-Yasin, the “first hijab-wearing woman” (re)elected to the Knesset. In the 2021 elections, Khatib-Yasin was fifth on the United Arab List (RA’AM); while the list won only four seats, Khatib-Yasin returned to the Knesset in August 2021 after the death of one of the party's male MKs, Said al-Harumi. Last but not least, in the newly formed government, nine women hold ministerial portfolios (Tables 5 and 6), which means both a record-breaking 33% female ministers and the presence of a critical mass of women who can push for feminist change, especially because most define themselves as feminist, including Merav Cohen, the Minister for Social Equality. To promote democracy and women’s rights, one of the priorities of a potential feminist agenda could be the adoption of gender quotas legislation, with sanctions for non-compliance, including in the Haredi and Islamist sectors. Such affirmative action laws, intended to compensate for women’s discrimination in the electoral process, are the most effective tools for increasing women’s descriptive and substantive representation*, i.e. for promoting democracy. In any case, for the moment at least, it seems a new (feminist) era has come.

* In June 2021, the Knesset plenum gave final approval to the so-called "Norwegian Law,” which allows any MK who is appointed as a minister or deputy minister to resign temporarily from the Knesset, thereby enabling a different member of their party slate to assume the position in their stead. In that context, more women entered the Israeli Parliament, and in September 2021 there were 34 women elected at the Knesset (28.3%), However, even with that increase, Israel has dropped to the 64th place on the IPU Women in National Parliaments Ranking (IPU 2021).

Hebrew

Abu Baker, Khawla. A Rocky Road: Arab Women as Political Leaders in Israel. Ra’anana: 1998.

Avgar, Ido and Etai Fiedelman. Women in the Knesset: Compilation of Data Following the Elections to the Twenty-fourth Knesset. Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center, 2021.

Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. “Feminine Organizations in Israel–Current Situation.” International Problems, Society and Politics 31 (1992): 65–76.

Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. Motherhood and Revolution: The Case of the Women in the Kibbutz, 1910–1990, Tel Aviv: 1992b.

Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. Democracy and Feminism: Gender, Citizenship and Human Rights, Ra’anana: 2011.

Friedman, Menachem. “The Ultra-Orthodox Woman.” In A View into the Lives of Women in Jewish Societies–Collected Essays, edited by Y. Azmon. Jerusalem: 1995.

Gedalya-Lavy, Einat. The Puzzle of Gender and Politics: Voting and Media Framing in Israel (1969-2013), PhD Dissertation, Political Science, Tel Aviv University, 2016.

Geva, Sharon. Women in the State of Israel: The Early Years. Jerusalem: Magnes Press–The Hebrew University of Jerusalem: 2020

Gorny Yossi. “The Second Alya: Changes in the Social and Political Structure of the Second Alya, 1904 -1914.” Hatsionut 1 (1970): 204-246.

Herzog, Hanna. Realistic Women: Women in Local Politics. Jerusalem: 1994

Herzog, Hanna. “Gender Blindness? Women in Society and Work.” In Israel Towards the Year 2000–An Initiative for Social Justice in Israel, edited by E. Margalit. Givat Haviva: 1996.

Herzog, Hanna. “Women in Politics, and Politics of Women.” In Sex, Gender, Politics, edited by D. N. Izraeli. Tel Aviv: 1999.

Herzog, Hanna. “Knowledge, Power and Feminist Politics”. In Hevrah be-marah (Society in Reflection), edited by H. Herzog. Tel Aviv: 2000.

Herzog, Hanna. “Women the Rising Power– Elections 1998.” In The 1998 Municipal Elections in Israel–A Change or Continuation?, edited by A. Brichta and A. Padatzur. Tel Aviv: 2001.

Herzog, Hanna. “Between the Lawn and the Gravel Path – Women, Politics, and Civil Society.” Democratic Culture 10 (2006): 191-214.

Izraeli, Dafna, N. “Gendering the Labor World.” In Sex, Gender Politics–Women in Israel, edited by Dafna N. Izraeli et al. Tel Aviv: 1999.

Konig, Ofer. The 35th Government, Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute: 2020.

Konig, Ofer. The 36th Government, Jerusalem: The Israel Democracy Institute: 2021.

Naveh, Hannah. “Life Outside the Canon.” In Sex Gender Politics, edited by D. N. Izraeli, et al. Tel Aviv: 1999.

Peres, Yochanan and Ruth Katz. “The Family in Israel: Change and Continuity.” In Families in Israel, edited by L. Shamgar-Handelman and R. Bar-Yosef. Jerusalem: 1990.

Raday, Frances. “Women in Israeli law”. In The Double Bind.: Women in Israel, edited by D. N. Izraeli, A. Friedman and R. Shrift. Tel Aviv: 1982.

Raday, Frances, Carmel Shalev and Michal Liban-Kooby, editors. Women’s Status in Israeli Law and Society. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: 1995.

Rosenberg-Friedman, Lilach. “The Religious Women Party in the First Knesset Elections: Failure or Achievement?” Iyunim: Multidisciplinary Studies in Israeli and Modern Jewish Society 32 (2019): 35-72.

Safran, Hannah. “International Struggle, Local Victory: Rosa Welt Strauss and the Achievement of the Women’s Franchise.” In Jewish Women in the Yishuv and Zionism, edited by M. Shilo, R. Kark and G. Hasan-Rokem. Jersualem: 2001.

Sasson-levy, Orna. Identities in uniform: Masculinities and femininities in the Israeli military. Jerusalem: 2006.

Shamir, Michal, Hanna Herzog, and Naomi Chazan, eds. Gender Gaps in Israeli Politics. Jerusalem and Bnei Brak: 2020.

Shapira, Assaf and Ofer Koenig. “Women’s political representation at the local level.” Jerusalem: Israel Democracy Institute, 2018. https://www.idi.org.il/articles/25472

Stern, Margalit Bat Sheva. The Revolutionary: Ada Fishman Maimon—A Biography. Jerusalem–Sde Boker, 2018.

English

Akirav, Osnat. "Women's Leadership in Local Government." Review of European Studies 13, no. 1 (2021): 77-90.

Akirav, Osnat and Yael Ben-Horin. "The Four Anchors Model–Women Political Participation." World Political Science 12, no. 2 (2016): 241-259. https://doi.org/10.1515/wps-2016-0007.

Avgar, Ido. Representation of Women in Local Government. Collected Data Following the 2018 Local Elections. Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center: 2019.

Avgar, Ido and Etai Fiedelman. Women in the Knesset: Compilation of Data Following the Elections to the Twenty-third Knesset. Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center: 2020.

Azmon, Yael. “War, Mothers, and Girls with Braids: Involvement of Mothers’ Peace Movements in the National Discourse in Israel.” Israel Social Science Review 12 (1997): 109–128.

Benski, Tova. “Breaching Events and the Emotional Reactions of the Public: The Case of Women in Black in Israel.” In Emotions and Social Movements, edited by Debra King and Helena Flam. London: Routledge, 2007.

Berkovitch, Nitza. “Motherhood as a National Mission: The Construction of Womanhood in the Legal Discourse in Israel.” Women's Studies International Forum, 20/5–6 (1997): 605-619.

Bernstein, Deborah. “Economic Growth and Female Labour: The Case of Israel.” The Sociological Review 31/2 (1983): 263-292.

Bernstein, Deborah S. The Struggle for Equality: Urban Women Workers in Prestate Israeli Society. New York: 1987.

Bernstein, Deborah S. “The Women’s Workers Movement in Pre-State Israel.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 12 (1987): 454–470.

Bernstein, Deborah S. Pioneers and Homemakers: Jewish Women in Prestate Israeli Society. Albany: 1992.

Boals, Kay. “Political Science.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1 (1975):161–174.

Chazan, Naomi. “Israel at 70: A Gender Perspective.” Israel Studies 23, no. 3 (2018): 141-151.

Fleischmann, Ellen. The Nation and its "New" Women: The Palestinian Women's Movement, 1920-1948. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. “The Struggle for Women’s Suffrage in Israel: 1917–1926.” In Pioneers and Homemakers: Jewish Women in Prestate Israeli Society, edited by D. S. Bernstein. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. “Navigating Gender Inequality in Israel: The Challenges of Feminism.” In Handbook of Israel: The Major Debates, edited by Eliezer Ben-Rafael, Julius Schoeps, Yitzhak Sternberg, and Olaf Gluckner, 423–436. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2016.

Franceschet, Susan, Mona Lena Krook, and Netina Tan, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Women’s Political Rights. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Freedman, Marcia. Exile in the Promised Land. Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1990.

Golan, Galia, and Tamar Hermann. “Parliamentary Representation of Women-The Israeli Case.” In Femmes et Parlements, edited by M. Tremblay, 251-275. Montreal, 2005.

Hacker, Daphna. “Divorced Israeli Men's Abuse of Transnational Human Rights Law.” Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 28, no. 1 (2016): 91-115.

Halperin-Kaddari, Ruth and Yaacov Yadgar. “Between universal feminism and particular nationalism: politics, religion and gender (in) equality in Israel.” Third World Quarterly 31, 6 (2010): 905-920.

Harel-Shalev, Ayelet, and Shir Daphna-Tekoah. Breaking the Binaries in Security Studies: A Gendered Analysis of Women in Combat. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Hasan, Manar. Murder of Women for ‘Family Honour’ in Palestinian Society and the Factors Promoting its Continuation in the State of Israel. M.A. Dissertation, University of Greenwich, England: 1994.

Hazelton, Lesley. Israeli Women: The Reality Behind the Myths. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1977.

Helman, Sara, and Tamar Rapoport. “Women in Black: Challenging Israel’s Gender and Socio-Political Orders.” British Journal of Sociology 48 (1997): 682–700.

Herzog, Hanna. “Minor Parties: The Relevancy Perspective.” Comparative Politics 19 (1987): 317–329.

Herzog, Hanna. “The Fringes of the Margin: Women’s Organizations in the Civic Sector at the Time of the Yishuv.” In Pioneers and Homemakers: Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel, edited by D. S. Bernstein. Albany:1992.

Herzog, Hanna. “Double Marginality:‘Oriental’ and Arab Women in Local Politics.” In Ethnic Frontiers and Peripheries: Landscapes of Development and Inequality in Israel, edited by O. Yiftachel and A. Meir. Boulder, Colorado: 1998.

Herzog, Hanna. “Homefront and Battlefront and the Status of Jewish and Palestinian Women in Israel.” Israeli Studies 3 (1998): 61–84.

Herzog, Hanna. Gendering Politics – Women in Israel. Ann Arbor: 1998.

Herzog, Hanna. “Why so Few? The Political Culture of Gender in Israel. International Review of Women and Leadership 2 (1996): 1–18.

Herzog, Hanna. “Redefining Political Spaces: A Gender Perspective on the Yishuv Historiography.” Journal of Israeli History 21 (2002): 1–2.

Herzog, Hanna. “Choice as Everyday Politics: Female Palestinian Citizens of Israel in Mixed Cities.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 22 (2009): 5-21.

IPU. Inter- Parliamentary Union. https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=9&year=2021 (2021).

Itzkovitch-Malka, Reut and Chen Friedberg. “Israel: A Century of Political Involvement.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Women’s Political Rights. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Izraeli, Dafna N. “The Zionist Women’s Movement in Palestine, 1911–1927: A Sociological Analysis.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 7 (1981): 87–114.

Izraeli, Dafna N. “Gendering Military Service in Israeli Defense Forces.” Israel Social Science Research 12 (1997):129-166.

Jajawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. London: Zed Books, 1986.

Kantola, Johanna and Emanuela Lombardo. “Strategies of Right Populists in Opposing Gender Equality in a Polarized European Parliament. International Political Science Review (2020): https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120963953.

Lachover, Einat. “Signs of change in media representation of women in Israeli politics: Leading and peripheral women contenders.” Journalism 18, no. 4 (2017): 446-463.

Gedalya-Lavy, Einat. The Puzzle of Gender and Politics: Voting and Media Framing in Israel (1969-2013), PhD Dissertation, Political Science Tel Aviv University, 2016.

Lemish, Dafna, and Inbal Barzel. “Four Mothers: The Womb in the Public Sphere.” European Journal of Communication 15 (2000): 147–169.

Lovenduski, Joni and Pippa Norris. Gender and Party Politics. London: 1993.

Pateman, Carole. The Sexual Contract. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Paxton, Pamela, Melanie Hughes, and Tiffany Barnes. Women, Politics and Power: A global perspective. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.

Phillips Anne. “Gender and modernity.” Political Theory 46, no. 6 (2018): 837-860

Raday, Frances. Economic Woman: Gendering Inequality in the Age of Capital. London: Routledge, 2019.

Sharfman, Daphna. “Women and Politics in Israel.” In Women and Politics Worldwide, edited by B. Nelson and N. Chowdhury. Yale University Press: 1988.

Shilo, Margalit. Girls of Liberty. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2016.

Swirski, Barbara and Marilyn Safir, eds. Calling the Equality Bluff: Women in Israel. New York: Teachers College Press, 1991.

Triger, Zvi. “Golda Meir's Reluctant Feminism: The Pre–State Years.” Israel Studies 19, no. 3 (2014): 108-133.

Tzameret, Hagar, Naomi Chazan, Hanna Herzog, Yulia Basin Brayer, Ronna Garb, Hadass Ben Eliyahu, and Yael Hasson. The Gender Index -Gender Inequality in Israel- COVID־19 Spotlight. Jerusalem: 2020.

Wodak, Ruth. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Sage: 2015.

Yuval-Davis, Nira. “The Bearers of the Collective: Women and Religious Legislation in Israel.” Feminist Review 4 (1980): 15–27.