Poverty: Jewish Women in Medieval Egypt

The documents recovered from the Cairo Genizah give insight into the lives of Jewish women in poverty in medieval Egypt. Without husbands, women were often left without any means of earning a living. The Jewish community did assume responsibility for providing for widows, and Jewish marriage contracts gave widows some financial protection, but the communal funds and the “delayed” marriage payments were often insufficient or not available to the women who needed them. Divorcées were also in precarious financial positions, while absentee husbands also often left their wives destitute. The Genizah also provides a window into the charity of wealthier women, such as Wuhsha the Broker.

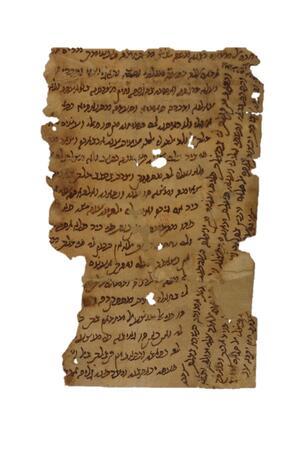

Women in the Cairo Genizah

For lack of sources, it is normally almost impossible to say anything about women and poverty, especially as regards the Middle Ages. However, due to the fortunate preservation of the letters and other documents from everyday life discovered in the Cairo Genizah we are able to sketch a fairly detailed case-study of Jewish women and poverty in medieval Egypt, particularly in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. We gain an understanding of the extent to which Jewish women in medieval Egypt became victims of poverty by virtue of being women and of the strategies they employed to deal with their plight. In the Genizah letters we are often able to hear the voices of women themselves, and we find them in abundance collecting alms on the poor rolls of the community. To be sure, the Genizah gives us only a partial picture of women and poverty. The needy women who appear in the Genizah records are mainly those who were not able to find succor in the bosom of their families. Those who did, did not leave a documentary trail.

Jewish Law and Women’s Poverty

The great Genizah scholar S. D. Goitein wrote: “[F]or the wife, the death of her husband was a disaster. She lost her support and even her domicile and could rely only on the remnants of her dowry, her other possessions, and the promised late marriage gift, all of which were often uncertain and insufficient assets. Indigent widowhood was a calamity for the woman concerned and an imposition on the community.” The Genizah papers portray the plight of widows attempting to collect the debts owed them by stipulation in their marriage contracts. We witness struggles over property between widows and the heirs and business partners of their deceased husbands. We read about widows as executors and guardians of their husband’s estates. We observe their valiant attempts to feed and clothe their minor children with often paltry child-support allotments. We are privy to stories about difficulties women experienced finding and keeping adequate domicile. The stories are not confined to widows. The documents embrace other women as well in their role as supplicants for charity.

In their susceptibility to indigence, divorcées (and divorce was frequent in the Genizah world) were not much better off than widows. Both had claim to the “delayed” marriage payment promised by their husbands in the marriage contract and to the principal amount of the dowry they had brought with them into the marriage. But then, as now, women could not always easily collect, or collect everything. Even when the money was there, widows and divorcées alike had to hope their husbands or their husbands’ heirs would pay up. (In divorce, a wife could waive these rights in order to “initiate” termination of an unhappy marriage). Jewish law did not automatically award widows any additional part of their husbands’ financial estate. They were, however, eligible under certain conditions for maintenance for themselves as well as for their children after their husbands’ death (whereas divorcées could only collect maintenance for their children) and sometimes took possession of other property of their husbands if the latter had specifically stipulated this in their wills or made a gift to their wives prior to their death (often with the condition that they not remarry). Depending upon the amount of their husbands’ contractual obligations and their own success in collecting their due, widows and divorcées might suffer greatly from the loss of their marriage.

The Jewish court and by extension the community were both in legal theory and in practice “the father of orphans and the judge of the widows.” This mandate was based on a characterization of God in Psalms (68:6; cf. Deut 10:18) and is amply attested in the Genizah. Rabbinic literature speaks mainly of orphans (“the court is the father of orphans”): the complete biblical phrase, “father of orphans and judge of widows,” is not very common. But the Genizah demonstrates that the court took the part of both. It tried to assure that widows as well as orphans received their due. The The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic protection assumed even broader application, as even deserted or neglected wives expected help from the authorities on this basis.

Stories of Impoverishment

Some women describe themselves as “a widow during (his) lifetime” (armalat al-hayyat, mimicking the biblical phrase almenut hayyut, 2 Samuel 20:3). This stands in for the normal rabbinic expression, Woman who cannot remarry, either because her husband cannot or will not give her a divorce (get) or because, in his absence, it is unknown whether he is still alive.agunah, literally, “anchored,” describing a woman whose husband is missing and who thus cannot remarry until there is testimony that he has died.

Particularly intriguing is the complaint concerning a wife whose husband had deserted her and their children to join a Sufi monastery in the hills around Cairo. Nearly perishing “from loneliness and from the quest for food for her young children,” she petitions the head of the Jews, the Nagid David II b. Joshua (1355–1374), the great-great-great grandson of Moses ben Maimon (Rambam), b. Spain, 1138Maimonides, to take steps to return her husband to the fold. Being realistic she writes, “Your handmaid does not wish from him what is beyond his capacity, nor (to be raised to) the level of ‘surplus.’ Your handmaid seeks only to remove him from the mountain and have him take care of his young children.” The concept of “surplus,” ghinā, is significant in defining the poverty line in Islam.

Next to outright desertion, absenteeism looms large as a cause of wives’ impoverishment. Husbands traveled frequently and widely for business and other reasons, sometimes for long periods of time, and often did not provide adequately for their families in their absence. We hear about the trials of women in this situation or in other situations of isolation when they took things into their own hands; for instance, the woman with an affliction in her hand who could not work and who “went out on her own seeking sustenance for herself and her dependent children.” The following Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsum found in the Genizah also shows how a woman might tactically use what little power she had at her disposal.

What does our lord, may your glory be exalted and your greatness increase, say regarding a woman whose husband, the Priests; descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses, who were given the right and obligation to perform the Temple services.Kohen, went on journeys once, twice, three times, and she never knew when he was about to travel? He did not leave her enough to eat or drink. So she took an oath causing fright to the mountains that she would not stay with him after this time. Whenever anyone speaks to her about making peace with him she renews her oath that she will not live with him.

Two Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsa of Maimonides (not from the Genizah) relate the fascinating case of a wife whose husband was frequently absent and who took things into her own hands to ward off poverty. Destitute, with a growing family, first one, then two children, she turned in desperation to working as an elementary school teacher with her brother (unusually for a woman, she had learned to read the Bible). The husband, who had returned but was no longer living with his estranged wife, protested at her working out of the house, especially since her brother had gone away and left the business in her hands alone. Jewish law frowned upon women working as teachers of young children, fearing possible sexual improprieties with the children’s fathers. If she refused to abandon her job and come home to live with him as a dutiful wife, he wanted to take a second wife (to divorce her would have meant alienating her share in the family home to another man if she remarried). Maimonides had some good advice for her: She ought not to be teaching, but if she wished, she could forfeit her late marriage payment and secure her divorce, in which case she would be free to teach whomever she wanted.

Another woman who took things into her own hands is the “poor foreign woman” Hayf?’, who came from Acre in Palestine. There her husband, a silk weaver, had abandoned her pregnant (no birth is mentioned). Later he returned, “stayed with me until I was with child,” and went away again. She gave birth while he was gone, reared her son until he reached a year old, whereupon the wandering husband returned. Soon driven from their home because of some unspecified incident, they arrived in Jaffa. There the husband again deserted his wife. When she attempted to return to her own family, they rejected her, so she resolved to travel to Egypt, collecting public charity on the way. She tried to catch up with her elusive husband in Malij, a town north of Cairo, only to learn that he had left his brother’s home there to return to Palestine. In her plaintive letter she appeals for assistance to a Jewish notable in the capital (Old Cairo, where most of the Jews lived).

We are struck by the number of women like the luckless Hayfā, on the move in a society in which women normally stayed out of the public eye. But grinding poverty often compelled women to take to the road. The most extreme case is that of a proselyte widow who, with courage and fortitude, left her home in southern France and traveled across the Pyrenees to Christian Spain. There she lost a second husband. Still pursued and harassed by her Christian relatives and threatened with dire punishment by the local church, she fled from the Christian North to the Muslim sector with a letter of recommendation from the local Spanish Jewish community and got as far as Old Cairo, where the pair of letters of recommendation on her behalf ended up in the Genizah. Perhaps she died or remarried in Egypt a third time and no longer needed the letters of recommendation. Or perhaps, simply, her letters had become so worn and tattered by the time she reached Egypt that they were no longer readable and in consequence were buried in the Genizah.

Records from the Genizah

Most of the indigent women who wrote seeking assistance or had others write on their behalf turned to communal officials, such as judges, or to the community as a whole. This was a gendered phenomenon. The men were more likely to write to private individuals or to carry letters of recommendation addressed to private persons asking that they provide the needy letter-bearer with assistance. If, as seems to be the case, the women were more accustomed to turn to Jewish officialdom, this certainly can be explained by the norms and etiquette of society. Turning to a man outside her family meant unwanted exposure, unless the man had some official function in the community. This preference on the part of women for addressing appeals to the community was strengthened, especially for the widows, most of whom had children, by the concept that the court is “father of orphans and judge of widows.”

The letters and legal documents mostly portray women seeking private charity and hoping to avoid the public exposure resulting from collecting alms distributed publicly by the community. But many Jewish women, especially the widows, confirming the ancient topos of “widows and orphans,” the typical weak persons vulnerable to poverty, experienced such extended dearth that they had to turn to public welfare.

How many such women do we find on the public dole? An enormous number, not unlike the high proportion of women found on lists of needy Christian recipients of charity where available. If we attempt a sociological breakdown of women on the alms lists, trying to distinguish, for instance, between widows, divorcées and abandoned wives, we are immediately faced with terminological difficulties. The entries do not always unambiguously reveal the women’s marital status. The word most frequently used to identify a woman is imra’a or mar’a (usually spelled mara), whose root meaning is “woman” but which is also the common Arabic vernacular term for wife. Goitein believes that the vast majority of women designated by the neutral word imra’a were actually widows. He thinks “wife” was employed euphemistically. Further, he posits, most of the single women with children on the alms lists must have belonged to this category.

We can accept that a large number, if not most, of those recorded as “wife” were in fact widows. There are simply too many of them and, relative to their numbers, too few called armala or almanah (“widow” in Arabic and Hebrew, respectively), to escape this conclusion, although we should nonetheless be careful not to overgeneralize. Sometimes it is possible from the way their names are recorded to identify women who were on the dole for reasons other than widowhood. There is no reason to presume, for instance, that “the wife of the apostate living in the inn of Abū Thinā,” the only woman so designated in the Genizah, was a widow. Her husband’s conversion to Islam would have left her abandoned, hence needy.

Women with incapacitated husbands must have turned to public charity precisely for that reason. Scribes seem to have listed them as such in order to delineate the specific reason for their need. One finds women called “the wife of the deaf man,” “the wife of the blind man,” or “the wife of the amputee.” On the other hand, the name Umm al-Yatīma (“mother of the orphan girl”) clearly describes a widow. It is difficult to decide the marital status of the pathetic Umm al-maflūj wa-mar’at al-aqta` David al-hammāl, “the mother of the semiparalyzed man and wife of the amputee, David the porter.” Was her husband still alive and did his family find itself on the dole because he was disabled? Were they divorced? Perhaps the woman was indigent for three reasons: she had both a child and a husband who were infirm and could not work, and her husband, to judge from his profession, belonged to the Jewish underclass.

Indeed, many other women receiving alms had husbands who were infirm, and this no doubt constituted the very reason they had had to resort to public charity. There is, for instance, “the wife of the man with the stomach ailment” who collected bread with her immigrant compatriots from Byzantium around the year 1107. Remembering that the documentation is serendipitous, all these examples should be taken as but a token sample of a much larger group.

The stories of these women recounted in the Genizah letters and their ubiquitous presence in the alms lists illustrate how widespread female indigence was. Most of this was a matter of gender. Normally unable to work, or at least earn sufficient income to support themselves and their children; often disadvantaged as widows or divorcées by a The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah that denied women inheritance rights and by a social reality that made it often difficult to collect their due from their marriage contracts, women sought charity because of vicissitudes related to their gender. The young woman who took her life into her own hands and worked as a teacher represents an exception to the rule. She went out into the world of men, flouting Jewish law, but she did so because, like other women of the time plagued by poverty, she would not let her children suffer if she could help it. More often than not, however, these largely disempowered women wrote letters of appeal to the community or lined up, alone or with their small children, to collect bread or other alms from public charity.

Charity in the Genizah

Women also appear as charitable figures. The most famous, or perhaps infamous woman in the Genizah is Wuhsha, whose Arabic name, coincidentally anticipating her love life, can be translated “Desirée.” Daughter of a Jewish banker from Alexandria, she lived in the eleventh century in Old Cairo, where the synagogue of the Genizah is located. Like the even more famous Glueckel of Hameln, who lived in Germany from 1646–1724, Wuhsha was a successful businesswoman, a broker, moving about in the company of men. Wuhsha was not totally unique—other women also appear working in the world of men—but she was unusual in her scandalous personal life, having borne a son out of wedlock at just about the time of her divorce from her husband, by whom she had a daughter. Among various papers relating to the life and activities of this independent woman we have her will, showing her to be quite wealthy and giving away about one-tenth of her assets to charities but, so she writes, “not one penny” to her son’s natural father. She never married him, doubtless because he had another wife in his hometown of Ascalon (Ashkelon), Palestine, who would not grant him permission to take a second spouse.

Only a handful of women appear on more than one hundred donor lists from the Genizah period. Women sought opportunities to fulfill the duty of charity. But the scarcity of women on the donor lists is wholly understandable, as women normally did not frequent the male-dominated venues—whether the synagogue or businesses—where collections were taken.

Cohen, Mark R. Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Cohen, Mark R. The Voice of the Poor in the Middle Ages: An Anthology of Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Gil, Moshe. Documents of the Jewish Pious Foundations from the Cairo Geniza. Leiden: Brill, 1976.

Goitein, S. D. A Mediterranean Society. A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. 5 vols. plus index volume by Paula Sanders. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967–1993.