Jewish Women in the Cairo Genizah

The discovery of the Cairo Genizah (950-125) in the late 19th century opened up a “world of women” that was previously unknown. A rich store of documents, including letters, wills, business arrangements, marriage documents, court cases, and rabbinic responsa, the Genizah sheds important light on the life of Jewish women – poor and wealthy, married, divorced, and widowed – in the Islamic world. While women were not in the mainstream of society, they played important roles in both the family and the community. Some were literate; many sent letters. Many also turned to the courts with documents reflecting powerful images of women teachers, widows, orphans, and others. Those with wealth left inheritances; those without were supported by the community, often turning to leaders with aid.

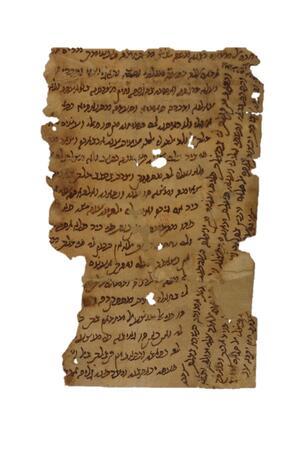

The late 19th-century discovery of the Cairo Genizah revolutionized the image of medieval Jewry in the Islamic World, in particular from the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. A genizah is a storehouse for sacred writings that are no longer in use, such as worn-out prayer books and imperfect or damaged Torah scrolls, which are usually buried, often in cemeteries.

Discovery & Research of Genizah Material

The Ibn Ezra synagogue in Fustat (Old Cairo), belonging to the congregation that followed the Palestinian prayer traditions, was destroyed in 1012. When it was rebuilt by 1040, an innovation was made to accommodate the storage of genizah material because there had been attacks on funeral processions when genizah material was also transported. A large chamber was built above the ceiling, akin to a room without a window or door and accessible solely through an opening reached by ladder. Material placed in this chamber remained for centuries, instead of decaying in the earth, as it would have if it had been buried. It was not emptied periodically as there was ample space. Egypt’s dry conditions were conducive to the unplanned preservation of the majority of these papers and books. After the community relocated to New Cairo in the mid-fourteenth century, use of this genizah was minimal.

The contents of the Genizah were most intriguing. Because documents that contained the name of God or used Hebrew letters were deemed sacred and the lingua franca of the Jews in Islamic Lands was Judeo-Arabic (Arabic written in Hebrew letters), anything written in this language (or in Hebrew or Aramaic) was considered appropriate to be stored there. Thus the material included sacred books, marriage documents, personal letters, court documents, business contracts, drafts of rabbinic decisions, poems, and more. This finding of “sacred trash” (a term aptly coined by Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole) proved to be a goldmine for scholars in numerous fields. It contained a vast amount of information about active and wealthy merchants, life in Egypt, Yemen, Spain, and India, dealings with Muslim rulers and courts, Karaites, yeshivot, magic, the poor as well as the famous, and much more.

The scholar who began to comprehend the significance of these documents for social and economic history was S.D. Goitein. Goitein was an eminent historian and Arabist whose pioneering work paved the way for generations of scholars. Rather than concentrating on one field or one specific genre, he attempted to reconstruct the society by reorganizing this hodgepodge of random material. His magnum opus, the six-volume A Mediterranean Society, prepared the path for further research and laid the foundation for understanding how this material could begin to be used. One of his most pioneering chapters was “The World of Women,” an unexpected and avant garde inclusion at the time. In each volume, examples of women’s activities or documents revealing aspects of their lives abound, but this chapter highlighted and synthesized material Goitein discovered, embellished by his personal insights.

Women, Work, & Finances

Goitein pointed to various professions in which women engaged and referred to them as excellent workers, although they did not play crucial roles in the economy and even those married women with earning capacity could retain their earnings only if their husbands permitted them to do so. The bride who prepared her trousseau displayed expertise in spinning and embroidery. Brides also acquired possessions by means of gifts, inheritance, and a dowry. Some owned and rented apartments or houses, stores, and other buildings, as attested to by contracts, lawsuits, and other documents in the Genizah. Women with the ability to invest could also serve as brokers. There were traditional paid positions such as midwife, keener, washer of the dead, bridal supervisor, and caretaker/cleaner of the synagogue or school. In the thirteenth century in particular, women were involved in the textile industry; women always wove and embroidered for themselves and for profit. Women teachers generally taught girls domestic skills such as sewing and spinning.

One eleventh-century professional woman, Wuhsha al-Dallala, daughter of a banker, was a well-known commercial broker in Fustat. Karima, nicknamed Wuhsha (“wild one”), married Arie of Sicily and had a daughter; the couple subsequently divorced. She later aligned herself with a lover from Ashkelon named Hassun, with whom she had a son, but she preferred not to marry him, most likely to protect her estate. At one point, she states that she had their relationship recorded by a Muslim notary, perhaps in order to make the liaison appear more respectable, but this seems highly unlikely. If they had done so, then by Muslim law Hassun would have inherited a large portion of her estate, which was clearly contrary to her intentions.

Wuhsha was active in the world of commerce and investments. In 1098 she did not bother to appear when summoned to the equivalent of small claims’ court, as it simply wasn’t worth her while. She had invested with her brother who set out on a commercial trip to India, but after he was murdered in 1104 she became involved in a long, convoluted lawsuit in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to reclaim her portion of the investment. She recorded a detailed will in which she divided her belongings between her siblings, other relatives, synagogues, and charity, specifying precisely who was to receive what. She hired a teacher for her son and included details regarding expenses for a lavish funeral. More documents relate to her than any other woman in the genizah.

Not everyone documented by the Genizah was as wealthy as Wuhsha; the collection includes many letters and petitions by the poor for help from the community or its leaders. Women could receive charity along with the men on Mondays and Thursdays, wheat or bread, rarely cash. Women might be taken captive; a letter from the poet Yehuda HaLevi concerns ransom payment of 33 1/3 dinars for the release of a young girl being held near Toledo. The poor were often desperate, while the wealthy left detailed wills as well as donations, such as oil for the synagogues so that learning could occur after sundown. The wealthy owned slaves, who often became like family members and did a tremendous amount of the housework and childcare. It should be noted that men often became sexually involved with female slaves and maidservants, sometimes even converting and marrying them.

Education & Literacy

The question of literacy among Genizah women arises frequently. Who was able to read? If so, was this because of private tutors? Who could write?

Hints about women’s literacy can be found in a number of Genizah documents. For example, the Genizah included verses composed by an erudite woman, the wife of the eminent tenth-century poet Dunash ibn Labrat, who composed her verses in a sophisticated Hebrew. More information can be found in a question posed to the sage Maimonides, in which a blind teacher explained that his income derived from teaching young girls the prayers in Judeo-Arabic, as well as teaching them blessings; a father had hired him to give the girls lessons in their home. Similarly, a letter sent by a brother to his sister after their beloved mother passed away indicates that the sister, Rayissa, was quite literate; not only was she clearly able to read what her brother had written, but he also sent her books of consolation in both Hebrew and Arabic.

Two late 12th-century questions posed to the sage Maimonides allow us to reconstruct the story of a woman who lifted herself out of dire poverty, essentially through her literacy. Married off at nine, she had been promised the support of her mother-in-law for ten years but received the support for only seven. After her husband left her to fend for herself and an infant son, she turned to her brother, a teacher, for employment. Her husband had initiated her into the world of literacy, and her brother gave her further instruction so she could serve as a teacher with him in the elementary school. When her brother opted to travel abroad, this woman was able to continue in his stead.

Ironically, when the husband returned and discovered she was teaching, he objected vehemently to her chosen profession. He mentioned his objections in the second of the two questions in which he sought permission to take a second wife. His request was denied because of a protective clause in his wife’s marriage contract, but he was informed that as her husband he had the right to bar her from working. His wife subsequently approached the rabbinic court with a query of her own, asking whether or not her husband was obligated to support her, as commanded in the Bible. This woman’s knowledge not only gave her the inner strength to approach the court, but also acquainted her with the requirements of Jewish law found in the Torah. This case also highlights the fact that the Jewish community of Fustat not only accepted but also respected this woman as a teacher, for they continued to bring their sons to her school when she was running it on her own rather than going elsewhere. She supported herself and her two sons and paid rent, obviously making a decent living. It is not easy to determine if other women were also employed as teachers in boys’ religious schools. Clearly the general level of literacy of women could not compare to that of men.

Women’s Lives as Revealed in Letters

Letters sent by women (often but not always dictated to family members or professional scribes) reveal a great deal about women’s concerns and lives. Some are mainly news updates for husbands, fathers, and brothers who had travelled for business purposes in which women expressed their concerns. Others related misfortunes: descriptions of suffering abound, ranging from attacks on the community to famines and sickness to personal disasters. When in need, women would first turn to their male relatives (fathers, uncles, and often brothers) for support before turning to public or private non-familial sources The centrality of kinship and family ties is evident, as is the responsibility men had for their female relatives and the ways women pressured and expected men to support them. Letters also reveal the concerns of orphans, especially female orphans, who were always in the weakest positions in society. Almost all of these letters were composed in Judeo-Arabic; the women’s letters are usually less formal than the men’s, often reflecting their everyday language. However, women from more educated families, such as Miriam, the sister of Maimonides, also sought aid from male relatives.

The level of mobility of this society required a great deal of correspondence. Male merchants travelled to Africa, the Land of Israel, Damascus, Yemen, Spain and India. Some were away for extended periods of time and needed to leave their wives and families with some means of support or to send them merchandise to sell. Letters were sent and received by wives and sisters among others.

Divorcées and widows often sent letters revealing their troubles. There are records of widows being evicted from their homes by stepchildren and even being beaten in order to bar their entrance to these homes. There are men who divorced their wives without making the promised payments. There are also women whose husbands disappeared without having divorced them, leaving them in limbo, unable to re-marry and often unable to support themselves and their children.

Illness often brought a family to the brink of bankruptcy. In 1120 a widow named Sitt l-Husn explained that her husband had been a well-respected man who supported his family until he fell ill; all their funds had been depleted due to medical expenses. She asked the community to grant her a stipend that would be the equivalent of loan to her infant daughter; the request was granted. The Jewish court was seen as the replacement for fathers of orphans and a source of aid for widows who had to deal with the shame of losing face. Seeking aid from individuals or community officials was seen as a way to conceal the embarrassment of openly asking for charity.

Women’s Wills

The Genizah documents include women’s wills, which reflect women’s values and priorities. By Jewish law, a woman does not automatically inherit, whether she be the wife or daughter of the deceased. However, if a will specifically states that a woman is to inherit, the testament is valid. In the Genizah are wills left by men who bequeath to women or who appoint them as guardians, in charge of their children and/or their assets; there are also wills left by women, the majority by those of means. Goitein published and translated many of these wills. One woman begged her sister to make sure her younger daughter received an education. Another woman arranged for herself to be buried in the garden until another family member died and could join her in a plot; she also chose her son’s future bride. A woman who was attached to her maidservants left them inheritances so that they could convert and would have proper dowries.

Women’s Use of Courts

Sometimes women felt they had been treated unjustly. Some opted to state their case by disrupting Sabbath prayers, a practice allowed when the court or community ignored one’s plight. Some threatened to take their complaints to Muslim courts. At times the threat sufficed to pressure the Jewish court to deal quickly with the matter at hand, but some women indeed carried out their threats. When this occurred, the Jewish court would have to bow to the decision of the Muslim judge, the qadi, because the law of the land is the law that must be accepted. Women were not loathe to approach qadis; wealthier women or those of a higher status seem to have been more comfortable approaching Muslim courts, while weaker women tended to make threats that they did not necessarily carry out. Some of the women had contact with their Muslim neighbors, who aided them during domestic conflicts. Others registered their monetary rights in Muslim courts for safekeeping so that male family members could not deprive them of their property. Records of debts, for example, could pressure the Jewish court to take action. The cases women brought to the Muslim court usually involved matters such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. The Jewish court viewed these actions as threatening even if the women had first unsuccessfully approached the Jewish courts. Turning to Muslim courts prodded the Jewish court to act or to reconsider a previous decision.

Marriage & Legal Negotiations

The age of brides ranged from early teens to early twenties; no set formula has been found but the sense is that they were at least thirteen or fourteen. Dowries were very detailed, as the bride was entitled to her dowry in case of divorce. Even the orphan needed a dowry to protect her from humiliation. Divorce in this society was more prevalent than previously imagined and does not seem to have created problems for the divorced; widows and divorcées often remarried. Matchmakers do not seem to have existed, but grooms appear to have courted a desired bride’s male relatives in order to obtain the desired match.

Many ketubot (marriage contracts)included a “monogamy clause,” a term coined by Mordechai Akiva Friedman to refer to a clause that fathers of the bride could include when negotiating with the groom. Because polygamy was common in Muslim society, Jewish men felt comfortable taking second wives. However, the Nagid Mevorah ben Saadya, the head of the community, created a clause in 1100 which he hoped would be used in order to prevent the taking of a second wife or maidservant against the wife’s wishes, severely limiting the husband’s options. This clause, frequently included after 1100, stated that if the husband did not respect his wife’s wishes, he had to grant her a decree of divorce and pay her the late payment or me’uhar, the second half of the bridal payment. This late payment was intended to protect a wife in case of divorce or widowhood and to dissuade the husband from offhandedly divorcing his wife, leaving her destitute; likewise it provided some funds for the widow if her husband predeceased her.

Other clauses in marriage contracts could limit the length of the husband’s absences, forbid him from relocating or even travelling without his wife’s permission, or determine with whom the newlywed couple would live. When the husband was involved with India trade, meaning a lengthy absence, he often gave his wife a paper that guaranteed her a divorce if he did not return after four years. Many of these clauses became fairly standard as of the twelfth century, and other clauses served individual needs, such as allowing the woman to work and retain the profits.

Even something seemingly simple such as visiting the bathhouse had to be negotiated because a husband had the right to limit his wife’s public appearances. However, since the bathhouse played a central role in the lives of these women, most men did not object to these visits. Goitein believed it was essential for maintaining a healthy body and mind. It was the one place in which women could socialize without supervision, without any male presence. Interestingly, the community recognized the importance of visits to the bathhouse. A husband was obligated to provide his wife with the necessary coin for the entrance fee; he was forbidden to prevent her from frequenting the bathhouse. Indeed, if he hoped to move to a locale without a bathhouse, his wife could rightfully object and refuse to be relocated. One extremely controlling husband was commanded by the court to allow his wife to go there, as well as to visit her family and attend celebrations.

Karaite Women in the Genizah

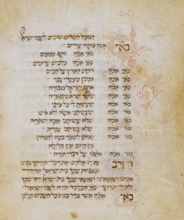

While the Geniza was located in the Synagogue of the Palestinians (one of the three synagogues in Fustat, alongside the Babylonians and the Karaites), it contains documents that shed light on the Karaite community as well. The Karaites followed the belief that one abides only by the written law in the Torah, rejecting oral law as recorded in the Talmud. As a result, their observances are quite different. In the early middle ages, they separated themselves from mainstream Judaism, yet some lived in medieval Cairo and had contact with the other communities. Among these documents were marriage contracts involving Karaite couples as well as intermarriages between Karaites and Rabbanites. Mutual declarations by the bride and groom appear only in the Karaite contracts, all of which are written in Hebrew rather than in Aramaic. In the case of an intermarriage, declarations of respect for the other’s traditions and lifestyle are made. In a marriage settlement published by Goitein, the husband promises not to force his wife to use light on Friday night or to insist she abrogate the holidays determined by the Karaite calendar. On the other hand, the wife promised to observe the Rabbanite holidays with her husband.

Conclusion

While women were not in the mainstream of Genizah society, they played important roles in the family as well as in society. Those with wealth left inheritances; those without were supported by the community and often turned to leaders for aid. Some were literate, reading and even writing; many sent letters, mostly to family members, necessary due to the mobile nature of this merchant society. Many turned to the courts; powerful images of women teachers, widows, orphans and others are reflected in these documents. Jewish women had contact with Muslims, sometimes appearing in their courts, and needed clauses in their marriage contracts to prevent their husbands from taking more wives as did the Muslims. The Judeo-Arabic documents from Cairo have opened up a “world of women” that was previously unknown.

Cohen, Mark R. Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Cohen, Mark R. The Voice of the Poor in the Middle Ages. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Frenkel, Miriam. “Slavery in Jewish Medieval Society under Islam: A Gendered Perspective.” Männlich und weiblich schuf Er sie, edited by Matthias Morgenstern, et al., 249-259. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011.

Friedman, Mordechai A. “The Ransom-Divorce: Divorce Proceedings Initiated by the Wife in Mediaeval Jewish Practice.” Israel Oriental Studies 6 (1976): 288-307.

Friedman, Mordechai A. Jewish Polygny in the Middle Ages [Hebrew] Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1986.

Friedman, Mordechai A. Jewish Marriage in Palestine: A Cairo Geniza Study, 2 vols. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 1981.

Goitein, S.D. A Mediterreanean Society: The Jewish Communities of the World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, 6 vols. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1967-1993.

Hoffman, Adina and Cole, Peter. Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza. New York: Schocken, 2011.

Krakowski, Eve. Coming of Age in Medieval Egypt: Female Adolescence, Jewish Law, and Ordinary Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Olszowsky-Schlanger, J. Karaite Marriage Documents from the Cairo Genizah: Legal Tradition and Community Life in Mediaeval Egypt and Palestine. Leiden: Brill, 1998.

Levine Melammed, Renée. "He Said, She Said: A Woman Teacher in Twelfth Century Cairo." AJS Review 22 (1997): 19-35.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “Spanish Lives as Reflected in the Cairo Genizah.” Hispania Judaica 11 (2015): 93-108.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “A Look at Women’s Lives in Cairo Genizah Society,” The Festschrift Darkhei Noam, edited by Carsten Schapkow et al., 64-85. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “S.D. Goitein’s ‘World of Women,’ Revisited”, Nashim 32 (2018): 102-110.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “A Look at Medieval Egyptian Jewry: Challenges and Coping Mechanisms Discerned in the Cairo Genizah Documents,” From Catalonia to the Caribbean: The Sephardic Orbit from Medieval to Modern Times: Essays in Honor of Jane. S. Gerber, edited by Federica Francesconi et al., 100-113. Leiden: Brill, 2018.

Zinger, Oded. “`She aims to harrass him’: Jewish Women in Muslim Legal Venues in Medieval Egypt.” AJS Review 42 (2018): 159-192.