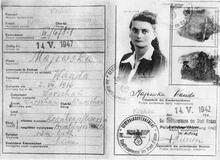

Anna Rozental

A future leader of the Eastern European Jewish socialist movement, Anna Rozental became aware of society’s inequities when her family moved from the Polish city to the countryside, where she observed the plight of laborers and peasants. She moved to Vilna and was introduced to the Vilna Group, the precursor to the General Jewish Labor Bund. Through revolts and imprisonment Rozental remained a committed party member and after the First World War she emerged as a leader in the Bund, becoming secretary of the central committee and chairwoman of the Vilna organization by 1924. In the last Polish municipal election before the Second World War, she was elected to the Vilna city council. She was arrested by the Soviet secret service and died in a Soviet prison during the war.

Anna Rozental belonged to the generation of Bundists who had already been active in the founding phase of the party under the Russian Empire and who were highly respected as “veterans” in the Polish Bund of the interwar period. From her youth on, Rozental’s life was closely tied to the Jewish labor movement in Vilna, where she died in Soviet custody during World War II.

Early Life: Gaining Awareness in the Countryside

Anna Rozental, née Heller, was born on October 14, 1872, in Volkovisk (Vilkaviskis, 62 km SW of Kaunas) in the province of Grodno. Her family was one of the wealthiest and most respected in the city. Her grandmother was a successful businesswoman and hotel owner, and her father, like many other relatives, was in the lumber business. Anna and her siblings and half-siblings (her mother was her father’s second wife) had a sheltered childhood. They were instructed at home by private tutors, including the later co-founder of the Bund, Vladimir Kossovski (1867–1941). At the age of six, however, after her father’s bankruptcy, she and her parents and sisters had to leave Volkovisk. From then on they lived in the country on an estate which they leased. The young Anna went through a phase of enthusiastic piety, which was however soon replaced by a love of literature, in particular the Russian classics. As a girl, like many of her contemporaries, she already dreamed of learning a profession and becoming independent. She also developed an early awareness of the hardship and suffering of the day laborers and peasants she saw around her.

Discovering the Bund and the Movement

The politicization of her social conscience occurred only after her move to Vilna, where she trained first as a teacher and then as a dentist after her father’s death in 1889. She was active for a time in the Zionist organization Members of Hibbat ZionHovevi Zion and read Hebrew literature. Through her mathematics teacher Arkadi Kremer (1865–1935), however, also a co-founder of the Bund in 1897, she came into contact with its precursor organization, the Vilna Group, and joined the Zhargonishe komitet, which devoted itself to disseminating Yiddish literature among workers. It was there that she also met her future husband Pavel (Pinai) Rozental (1872–1924), a medical student, and became active in further education for workers in the so-called circles, the groups of organized workers. At that time she was apparently particularly impressed by the early works of the Marxist theorist Georgy Plekhanov (1856–1918). With her husband, now a physician, Anna Rozental moved in 1899 to Bialystok, where she worked as a dentist. After the arrest of the first Bund central committee, the couple also became part of the party leadership. Both of them were arrested in 1902 by the Tsarist authorities and banished to Siberia, where they participated in a revolt of exiles. After being released as a result of the Russian Revolution of 1905, they returned to Vilna, where they continued their work in the Bund, in spite of the repression that accompanied the crushing of the Revolution and despite renewed arrest and exile.

Party Leader and Youth Advocate

The turmoil of World War I finally took the Rozentals to Saint Petersburg, where Anna Rozental became Secretary of the Bund central committee in 1917. After lengthy sojourns in Moscow and Kiev they returned to Vilna in 1921. In the years that followed they were among the leading personalities in the Bund there, who succeeded in overcoming the fierce struggles between the left and right wings of the party and integrating the Vilna Bund into the new realities of the Second Polish Republic. After the death of her husband in 1924 Anna Rozental assumed the chairmanship of the Bund organization in Vilna and also became a member of the party’s central committee in Warsaw. Until her arrest at the beginning of World War II, her apartment at 60 Zelazna Street in Vilna was a focal point for all the Bundists in the city.

The secular Jewish school movement and work with children and youth were particular concerns of Anna Rozental’s. As a member of the executive of the TSYSHO (CISZO) Central Jewish School Organization and the Bundist women’s organization YAF (Jewish Women Workers), she was involved in setting up Yiddish schools and children’s daycare centers in Vilna. She also introduced TSYSHO’s work in a lecture given at the international women’s conference that was held during the congress of the Socialist International in the summer of 1931, in Vienna. In 1938, in the last Polish municipal election before World War II, Anna Rozental was elected to the Vilna city council. The Bundists under her leadership formed the largest Jewish faction on the council. Rozental was also active as a journalist and political writer, dedicating a large portion of her work to the pioneer generation and history of the Bund.

After the outbreak of World War II and the first Soviet occupation of Vilna Rozental’s apartment continued for a time to serve as a sanctuary for Bundists who had fled the German occupation elsewhere. However, like many other Jewish socialists, she was arrested by the Soviet secret service and later died in a Soviet prison.

For her contemporaries, Anna Rozental embodied the inner continuity of the Bund from its heroic beginnings in the underground to the onset of World War II, which the party succeeded in maintaining despite the change of political context from the Russian Empire to the Second Polish Republic. For younger party members, she represented an authority who offered orientation, and thus helped to hold the two generations together.

Selected Works

“Pages from a Life Story” (Yiddish). Naye Folkstsaytung. November 19, 1939. Also published in YIVO Historishe shriftin 3 (1939): 416–437, and in Unzer Tsayt (1972).

“Women in the Bund” (Yiddish). Unzer Tsayt no. 3–4 (77–78) (1947): 60–63.

Davies-Kram, Harriet. “The Story of the Sisters of the Bund,” Contemporary Jewry V, no. 2 (1980): 27–43.

Fieseler, Beate. “The Jewish Legacy and Social Democracy. Women in the Bund and the Russian Social Democratic Workers’ Party at the Turn of the Century.” In Bund—100 lat historii 1897-1997 (Bund—100 Years of History. 1897–1997), edited by Feliks Tych and Juergen Hensel, 187–199 (Polish). Warsaw: Erich Brost Foundation in the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 2000.

Hertz, J.S., editor. Doyres bundistin (Generations of Bundists) (Yiddish), vol.1. New York: Unzer Tsayt, 1956, 180–192.

Tobias, Henry. The Jewish Bund in Russia. From its Origins to 1905. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1972.

Pickhan, Gertrud. “Gegen den Strom” (Against the Power). In Der Allgemeine Jüdische Arbeiterbund “Bund” in Polen 1918–1939 (The General Jewish Labor Bund “Bund” in Poland, 1918-1939). Schriften des Simon-Dubnow-Instituts, I. Stuttgart, Munich:

Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2001