Cecila Slepak

Cecilia Slepak, a journalist and translator, was a part of the intellectual elite in Jewish Warsaw. After the establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto, she joined the Oneg Shabbat group, which was vital in collecting records and interviews about life in the Warsaw Ghetto. She focused in particular on the lives of women in the ghetto as they struggled to survive, providing a unique window into the reality of the ghetto.

The Slepak Home

Cecila Slepak was a journalist and translator who lived in Warsaw. One of her major works was the translation into Polish of the twelve volumes of Simon Dubnov’s History of the Jews, which was published posthumously in 1948. Slepak’s home was a meeting place for Jewish intellectuals and had the reputation of being a pleasant place for cultural and social discussion. Her husband was an engineer; we have no information regarding children.

Slepak was a member of an intellectual elite immersed in secular Jewish culture and also integrated into Polish culture, who took a realistic and critical view of the Jewish community and of the conduct of individual Jews.

Rachel Auerbach, who was a young journalist and writer in Warsaw in the late 1930s, described a meeting in Slepak’s house in April 1940, during the German occupation and before the ghetto was established. She wrote that Slepak’s home still looked like a pleasant residence despite the many articles of furniture that the Germans had confiscated. Auerbach points out that the Slepaks and their guests were trying to conduct regular social engagements and intellectual conversation. She was very pleased to be invited to the Slepaks and perceived it as a great honor.

Documenting the Ghetto

We know very little about the Slepaks’ life in the ghetto. However, Cecilia Slepak was active in the underground initiative to document Jewish life under German occupation.

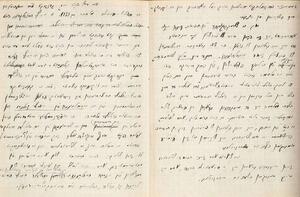

She was part of the team organized by Emmanuel Ringelblum and other Jewish intellectuals and public figures who were in charge of collecting letters, diaries, and other writings about people’s experience under German occupation. This was known as the Oneg SabbathShabbat underground archive. The archive team was interested in collecting information on Jewish life before the confinement in the ghettos, in the ghettos themselves, and in various labor camps. They interviewed people, inviting them to write their recollections and to hand them any writing and reflections that they could provide.

Towards the end of the first year of the ghetto in Warsaw (the end of 1941), Oneg Shabbat leadership initiated a wide-ranging research project entitled “Two and a Half Years of Nazi Occupation: One Year of Ghetto Life.” Commissioned to write on the life of women, Slepak interviewed sixteen women, a cross-section of those in the ghetto. She asked them about their lives before the war, their experiences during the siege of Warsaw, the impact of the first stages of occupation on their lives, how they responded to German regulations that stripped them of rights and possessions, their efforts to cope with the increasing pauperization of their families in the ghetto, and how they dealt with the starvation, diseases and unemployment in the ghetto.

Conducted during the winter and spring of 1942, Slepak’s interviews provide a unique description of women’s strategies for coping with the increased dangers that men and women alike were facing and their shifting patterns of accommodation, defiance and resistance.

Writing in the midst of the extraordinary situation in the Warsaw Ghetto, Slepak compared women with formerly unacceptable “occupations” such as theft, prostitution, and begging, with women engaged in traditional “women’s work” and in new occupations for women. She describes the lives of housewives; a cleaning woman; one who worked in the food storage centers, public kitchens and orphanages; and a woman who served on the house committees. She also wrote about women in the performing arts—a dancer, an actor, and a musician—as well as about small vendors, smugglers, and professional women such as an agronomist, a translator, and a librarian.

Slepak did not hesitate to describe the dark sides of women’s life and the reality that emerges from their life stories may be interpreted in different ways. We today look at the history of the ghetto residents with a clear image of the ghetto’s ultimate destruction, whereas for Slepak the ghetto was a forced reality to be accepted and criticized. She empathized with the women and their plight; she does not pass judgment on their choices, but views their activities as part of their effort to live.

None of the post-Holocaust terminology referring to the Jews as martyrs or saints appears in her report. She was viewing the rhythm of life around her with an open mind and with great respect for her interviewees, aware of their femininity. Nevertheless her own biases come through in her descriptions.

According to Emmanuel Ringelblum, Slepak was deported to Treblinka in the mass deportation from the ghetto in the summer of 1942. Her last interview was probably conducted a few weeks before she was deported. Another source regarding her death refers to Trawniki forced labor camp, where she was deported and killed in 1943.

Auerbach, Rachel. Warsaw Testimonies (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Moreshet, 1985, 49–54.

Ofer, Dalia. “Gender Issues in Ghetto Diaries and Interviews: The Case of Warsaw.” In Women in the Holocaust, edited by Dalia Ofer and Lenore L. Weizman, 143–167. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Ofer, Dalia. “Her View through My Lens: Cecilia Slepak Studies Women in the Warsaw Ghetto” (Hebrew). Yalkut Moreshet 75 (April 2003): 111–130 (in English: Memory, Place and Gender, edited by Tova Cohen and Judy Baumel).

Yad Vashem Archive (YVA), JM/217/4 and JM/215/3.

Ringelblum, Emmanuel. Ketavim Aharonim, vol. 2 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1994, 223–225.