Yemen and the Yishuv

The Jewish community of Yemen was very conservative, and tradition required that women’s lives would be carefully circumscribed from infancy to maturity and would be lived mostly within the household. Girls lived daily lives and life-cycle events according to a rigid schedule. Although they generally had no formal religious or secular instruction, the received a very structured education. Girls were often engaged to be married very young, but they lived with their husbands only after they matured. Women were a dominant force in the social, cultural, and family arenas. After immigration to Erez Israel and New York, they adapted to changing economic, social, and communal conditions, acculturated in language skills and organizational life, and were instrumental in bringing up their children to successfully integrate into the new worlds.

The one saying that was always associated with the Yemenite Jewish woman was “Kol kevudah bat melekh penimah”—she is honored as a princess within the confines of her home (Psalms 45:14). The Jewish community of Yemen was extremely conservative, both in its everyday lifestyle and in its Sabbath, holiday, and ritual observances and celebrations. Accordingly, tradition required that women’s lives would be carefully circumscribed from infancy to maturity and would be lived mostly within the household.

Traditional Life

From early childhood, Yemenite girls lived their daily lives and their life-cycle events according to an extremely rigid schedule. They did not go to the mori (the private school teacher) and generally had no formal religious or secular instruction. Nevertheless, they received a very structured education. From the age of four or five, they were gradually taught all aspects of housework in combination with the religious obligations that they would need later in life. For example, they learned how to follow dietary laws, to perform separation of During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah, the Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kashering (soaking and salting) of meat and the ritual immersion of utensils, to eschew forbidden foods, to say blessings for meals, for candle-lighting and for other occasions. They were also taught to adhere to dress codes, personal modesty, and the precepts concerning the menstrual cycle. These numerous and quite complicated instructions were given orally, as obligations, without any discussion of their philosophical or historical background. Women associated strict observance of these halakhot (religious Jewish laws) with yir’at shamayim (love and fear of God) and rarely challenged them. These practices were the ways of their mothers, grandmothers, and all previous generations. Jewish women saw themselves as one link in the traditional chain of thousands of years and took pride and comfort in this perception.

Yemenite women’s daily routine was strenuous. They had to rise before dawn to fetch water and prepare the gisher (Yemenite coffee), grind flour, bake, and have breakfast ready when the men returned from the prayer service in the kanis (synagogue) at sunrise. By the time a girl was about eight years old, she participated in all of the daily household responsibilities: cleaning, washing, cooking, sewing, etc.

Yemenite girls were often engaged to be married before they were twelve years old and were not able to choose their future husbands. When young children were orphaned, there was a danger that the Yemenis might force their conversion to Islam and remove them from the Jewish community. Thus, marriages of very young people were often arranged to prevent this tragedy. However, young girls apparently lived with their husbands only after they matured. Marriage to older men was not unknown, and neither was polygamy. The major circumstance leading to polygamy was the practice of levirate marriage (a religious obligation to marry the wife of a brother who died without issue), which was encouraged among Yemenite Jews even into the twentieth century. Following her wedding, the bride moved to her mother-in-law’s house where she joined the pool of female workers, continuing the same arduous tasks for which she had been trained by her own mother.

The wedding was definitely the highlight of a woman’s life in Yemen. She was the center of attention not only on that momentous day, but for several weeks before and after the wedding. During this period, she was put on a pedestal and exempted from chores.

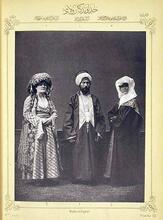

Today, the picture of Yemenite brides in their beautiful costumes bedecked with jewelry is regarded as the image of the Yemenite woman. Ironically, this image is not at all representative of most of Yemenite Jewish women’s lives. However, new mothers were given a few weeks to relax from her hectic routine. Friends would arrange a women-only celebration in the mother’s honor by dressing her in festive garb and hair covering specifically reserved for this occasion. Thus adorned, she reclined in a specially ornamented room scented by fragrant plants to receive guests and well-wishers.

Yemenite jewelry, known for its beauty and delicate filigree, is probably the most popularized of Yemenite art forms. In Yemen, jewelry was one of the luxuries enjoyed by women, for whom possession of a few pieces served as a status symbol. However, the wedding costume and its jewelry was not owned by each bride, but belonged to a wealthy member of the community who rented the ceremonial outfit repeatedly. This custom was continued in many Yemenite communities in Israel and abroad.

Poetry and Songs

Since Jewish women in Yemen generally did not read or write either Hebrew or Arabic, a major historical source for describing their lives is their oral poetry, which was recited in Yemeni Jewish dialects and has been compiled and translated into Hebrew and English. Their poems and songs documented their happy moments, aspirations, and disappointments on the personal as well as the more complex family and communal levels. This poetry often reveals internalized desires that were somewhat inconsistent, both with the mundane functions prescribed for them by tradition and with their smiling faces and festive dress at weddings. Although the treatment and status of women depended mostly on the particular household and the internal family relationships, some generalizations can nevertheless be made. The women understood that they functioned in a world whose order was largely unchanged and unquestioned and that placed them in well-defined normative roles. It is likely that most were content and fulfilled within the framework of their expectations.

Oral poetry was composed as a direct response to various situations and differed from region to region and town to town. The women’s singing while they worked together served both as an emotional outlet for their feelings and repressed sentiments and as an expression for their poetic talents. In addition, women sang and danced within their own circles on the happy occasions of the life cycle, always separate from the men. Recognized expert singers in every community received, as a family heritage, a reservoir of songs for every event. The singers also spontaneously changed, deleted, and added to the verses and were therefore composers and poets as well as performers and entertainers.

As the women labored at grinding flour, washing clothes in the river, carrying water from the spring, cooking, and sewing, they expressed themselves by singing. The elevation of the spirit during happy and sad times in women’s lives gave birth to these poems, which embody universal themes and appeal to women all over the world. During wedding ceremonies, empty tin cans and wooden tambourines were used to accompany the voices. There were many “separation” songs, such as those of young women leaving their mothers to become brides and others by wives of men who worked away from home and returned only for the Sabbath. Many of these poems bore some similarities to those of Yemenite Arabic women, since they express universal anguish.

The following verses from four poems express a range of emotions, love, and happy moments, as well as the frustration and bitterness of women who could not escape their destiny. These songs tell of sorrow, sadness, and yearning for a life of gentleness and love.

Nor his money.

I wish to have a young one

To play with and to kiss!

I do not want an old man

A broken scythe handle is he,

I wish to have a young one

To squeeze all the bones in me.

* * *

Why is it, my cousin-husband,

You are subjecting me to accepting another woman as your second wife?

If the cause is beauty,

I am as pretty as the moon and the stars.

If the reason is my locks,

Then I have two hundred braids.

Is it for children?

I have borne you two sons already.

If it is my character,

The neighbors will be my witness.

If my housekeeping and cooking are challenged,

The guests will be my references.

I hardly eat, I hardly spend.

So why, oh, why are you bringing a second woman

Who is far less valuable into this household?

Other poems/songs document the elevation of spirit of the Yemenite woman who is in love with her surroundings and her mate.

While I’m young, my blood sings within me.

My heart yearns for joy and singing,

My God, grant me a music box within me.

The sun rises, impossible to stop it.

Do not prevent desires from the soul.

My lover met me at the spring.

“Hello, my girl,” he said.

“You have enriched me.

Your hair is thick, beautiful and glorious.”

Whoever does not have a lover

Is truly deprived and miserable.

Women's Networks

Yemenite women were not part of synagogue functions and ceremonies. When and if they came to hear tefillot (prayers) and Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah readings, they sat in a separate room. They did not write religious texts and did not leave written memoirs. Thus, the historical narrative has mistakenly placed Yemenite women on the periphery of the South Arabian Jewish community. In Arab countries, one could hardly expect Jewish women to be mediators between the two societies, and they fulfilled no political function. Yet in the social, cultural, and family arenas, they were a dominant force and thus set the tone of daily life, in and around their homes.

Yemenite women were voluntary social workers. They helped poor brides in arranging wedding ceremonies, providing basic clothing, household equipment, assistance, and food. They supported orphans, the sick, and the elderly. It was generally accepted in Yemen that if one was able to help the needy, it was incumbent upon one to do so. While men and women did not participate together in these endeavors, the women were often the first to discover the needy and to begin helping them. In organizing to provide the help, they essentially created a women’s organization. While it had no president, officers, or board of directors, it definitely had active members who did the actual work. All these activities, such as assisting the needy, arranging weddings, cooking, singing, and dancing among themselves at happy occasions and working together at household chores, created a network of support groups where close-knit relationships developed and remained a most important and meaningful part of their lives.

In times of mourning (and these were not rare in Yemen), the women came together (they sat in a separate room during Lit. "seven." The seven-day mourning period held following the death of an immediate family member: spouse, parent, child or sibling.shivah) and more easily provided comfort to one another. Mortality was high and the women shared each other’s sorrows. Infant mortality reached dreadful proportions. It was not uncommon for a woman to give birth to twelve children and see only two reach adulthood. A special function thus emerged for some Yemenite women: official mourners. Referred to also as “wailing women,” they had the unique task of leading the women’s crying during the first three days of the shivah. This performance directed the other women in the group and focused their weeping. Wailing women came prepared with a memorized text that was modified spontaneously according to the situation and characteristics of the deceased. They were helpful both in verbalizing the family’s grief and in providing consolation. This exhibition was not merely an emotional outburst but was rather a calculated stimulant for the community’s involvement in mourning. The wailing tradition was generally not preserved once the Jews left Yemen. It seemed too harsh and was often considered “uncivilized” by European Jews.

Marriage was expected; it was a part of life. Men and women shared responsibility in marriage, but the division of labor was clear. Women were in charge indoors while the men’s responsibilities were outdoors, including shopping and providing a livelihood. Women were secluded and their clothing covered them from head to toe. Promiscuity was virtually unknown.

The total segregation between men and women in the public sphere of the Yemenite community created a natural female support group. The women listened to each other’s woes, consoled grieving and suffering friends and helped those who needed assistance in overcoming life’s hardships. In all these separate communal activities the women strengthened themselves and each other. In addition, their Jewish identity was clearly expressed through these charitable acts. Strong bonds developed among them and these friendships were very much valued and cherished in the many Jewish communities of Yemen.

Additional Tasks

In the towns, Jewish women hardly ventured out of the designated Jewish Quarter. They did not go to the market, and therefore had no business or social contact with Muslims. Fathers, husbands, and brothers shopped and brought food home. Jewish women were therefore spared the humiliations often suffered by male Jews at the hands of Muslims in public places.

In the villages and countryside, Jewish women did sometimes interact with Muslims, since they spent many hours outside their homes and neighborhoods. They collected firewood, brought water from the streams, and frequently took their baskets and other handmade ware for sale in the general market. They were also known to assist their artisan husbands in their crafts when necessary.

There were no inns for Jewish travelers in Yemen. Jews everywhere were expected to welcome and host Jewish sojourners who were passing through and needed to spend a night, a Sabbath, or a holiday. Therefore, much hospitality was practiced both in the towns and in the villages. Women were responsible for the additional food, water, and bedding and graciously accepted their role as generous hostesses who understood the importance of the mitzvah of hakhnasat orhim.

Yemenite women were also educators. In addition to training their daughters, mothers were in charge of sending sons to study in the kanis. They were also responsible for providing food (as a form of payment) for the traditional teacher, the mori, and his family. While she herself was not a teaching mori, she knew enough of Jewish law to teach her sons some blessings and A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvot and to make certain that they attended the synagogue. Mothers, aunts, and grandmothers influenced all the children in the extended household, particularly through ethical and moral instruction. In addition, popular idiomatic expressions and folkloric stories were used as teaching tools to instill manners and proper behavior in both sons and daughters.

Jewish women excelled in their capacity as healers. They learned effective techniques from their mothers or other women in the family. Many were known as popular “medicine-women” who knew how to use herbal medicines to cure illnesses. Some were called to bedsides many miles away. They also ably served as midwives.

Yemenite Jewish housewives/mothers were multi-task functionaries of their society. Although they were subservient to their husbands or mothers-in-law in some respects, they did have many opportunities to show initiative in dealing with numerous challenges within their sphere of influence. To a great extent, they made the family’s social wheels spin.

Emigration from Yemen

Early years in Erez Israel

The turning point leading to a gradual change in the status of women occurred with the immigration of Yemenite Jews to The Land of IsraelErez Israel/Palestine. The first Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah in significant numbers began in 1882 and coincided with the east European “First Aliyah.” Additional waves of Yemenite immigrants arrived in Erez Israel in the early 1890s and 1900s. By the year 1914, fully one-tenth of the Jewish population of Yemen had made aliyah, an unprecedented percentage as compared with other diasporas. On the eve of World War I, about five thousand Yemenite Jews lived in Erez Israel. Of these, some 3000 lived in Jerusalem, about 1100 in agricultural settlements (moshavot), and about 900 in Jaffa. In 1914 Yemenite Jews constituted about six percent of the Jewish population in Palestine. When the “Eagles’ Wings Aliyah” of 1949–1950 arrived in the independent State of Israel, it is estimated that the 50,000 arriving Yemenite Jews equaled the number already living there.

For the Yemenite immigrants, arrival in Zion did not mean a break with religion, old customs, or cultural heritage, but rather a precious opportunity to observe the commandments even more strictly in the sanctity of Jerusalem and other places in the Holy Land. They clung tenaciously to their traditional folkways and naturally expected the status, honor, function, and place of women to be as it was in Yemen. The Yemenites’ aspirations that their aliyah would serve as a religious redemption, as it is said, “rejuvenate our days as of old,” were not consistent with the secularist ideology of European Zionists.

In fact, the Yemenite immigrants confronted a quite unexpected reality, different from their hopes and dreams of maintaining their traditional ways. Conditions removed the women from the framework for which they had been trained and to which they were accustomed. It became evident soon after their arrival, both in Jerusalem in the 1880s and 1890s and in the agricultural colonies in the early 1900s, that the “old world order” could not survive. Often enough, only the women in the family could find more permanent employment (usually in domestic service) that provided the family’s meager subsistence. Under such circumstances, the men faced a major upheaval: employed women were out of the house for many hours. They gradually gained self-confidence, and because of their income their self-image evolved. They also became more sophisticated socially, acquiring knowledge of the ways of the world that many men altogether lacked. This upheaval was perceived as a serious threat to the fabric of family life and to the social and communal order.

In Jerusalem, Yemenite women struggled on several fronts. Their labor for meager pay was arduous and exhausting, and they sometimes suffered the verbal abuse and disdain of their employers. At the same time, they were confronted with mounting spousal disapprobation in direct proportion to their increasing independence. To make matters worse, a 1902 ruling of the Jerusalem Rabbinical High Court forbade the employment of Yemenite women without the express permission of their husbands. This petition by Yemenite men to the Jerusalem court and its ruling demonstrated a desperate attempt by the religious establishment to try to force the women to conform to their traditional roles. However, not only did the reality in Jerusalem exhibit a general disregard for this anachronistic decision, but even the rabbis of the court had to acknowledge in the latter part of their announcement that the status of Yemenite women was indeed changing. Showing contemporary sensitivity to women’s rights, in the same document they forbade the betrothal of girls not yet twelve years old and discouraged arrangements whereby young women were given as brides to elderly men. Nonetheless, family and communal coercion still kept women “in line” regardless of social and economic developments.

In the agricultural settlements, Yemenite women and men together endured abominable living conditions, lack of food, and a distressingly high rate of child mortality. They were sometimes employed in the fields, but the women also labored in the farmers’ households. There were reported incidents of public humiliation by the farmers that, although strongly condemned by Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi day laborers, nevertheless left deep scars on Yemenite pioneering women.

Literature portraying Yemenite Jews in Erez Israel ascribed a strong character to Yemenite women. Mordechai Tabib and Hayyim Hazaz both describe the women’s extraordinary strength and ability to cope with hardship and suffering; the women are regarded as able to face changes and challenges more successfully than their male contemporaries.

For the first generation of Yemenite women immigrants in the urban areas, menial work was almost the only occupation available outside their community. However, even though these were servile jobs and certainly did not represent upward socio-economic mobility, the environment the women encountered on a daily basis introduced them to an entirely different existence. It was often the daughters of this generation of immigrant women who fulfilled their mothers’ aspirations of breaking away. They gained an education and professional degrees in non-sectarian schools and led a more modern, western lifestyle, significantly improving their standard of living.

In addition, the pioneering experience in Erez Israel opened a path for young Yemenite women, allowing them sometimes to break away from their former constraints. In Yemen, there was no other Jewish “host society” that could have absorbed women rebel-refugees had they opted to leave their traditional framework. In Erez Israel, an exit from their social confinement (mainly into the Ashkenazi laborers’ circles) was indeed emerging even before World War I. Shoshanna Bassin’s romance with and marriage to an Ashkenazi secular and socialist laborer met with violent disapproval by her family. Her account points out the many obstacles in the path away from the traditional Yemenite community. Bassin and a few others like her soon discovered that their new milieu was at the end of a one-way road with no return to their ethnic community. In the post-World War I era, more Yemenite women opted for involvement in the prestigious and ideologically dominant labor circles in the country. Yemenite families gradually became more accepting of the new avenues these women chose. Bat Sheva Mauda-Oded, who in 1939 married Giora, the son of Alexander Zeid, the legendary Second Aliyah shomer (watchman), was wholeheartedly supported in her choice by her parents and siblings.

Unique and unusual was the Yemenite Jewish woman’s experience in the Cooperative smallholder's village in Erez Israel combining some of the features of both cooperative and private farming.moshav ovdim. Equality between husband and wife was one of the basic principles of this type of agricultural settlement, supported by the Zionist Movement. It was assumed that women would be full economic and social partners in the enterprise. Indeed, in most Yemenite families, husband and wife went out to work in the fields together, but women still had the responsibility of caring for the children, preparing meals, and performing other household chores. They were thus often forced to carry their babies while they worked at their farm chores. Yet Yemenite women fought for and succeeded in achieving equal standing in the land leasing agreement with the Jewish National Fund. They signed contracts and were co-lessees of the land and co-owners of the homestead.

The change in the women’s economic role did not immediately translate into any reform in their social status within Yemenite circles. Their absence from public life within their communities in Erez Israel contrasted significantly with the position of Eastern European pioneering women among their peers in the labor movement.

Rachel Zabari (1909–1995) was born in Yemen and came to Israel at an early age. She studied in Teachers’ Seminary and at the Hebrew University, was an active member of the Labor Movement, and joined the Haganah. A teacher and a supervisor for the Ministry of Education, she was also elected to the Second Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset and served continuously until the Sixth Knesset. This Yemenite woman reached the highest echelons of Israeli politics on the eve of and after the birth of the state. Although her accomplishment was exceptional, it nevertheless demonstrates the considerable distance Yemenite women traveled from their homes in Yemen to communal contribution at a most significant historical moment of the Jewish people.

In New York

In the late 1920s and early 1930s a few groups of Yemenite Jews settled in New York City, arriving in the United States via Erez Israel. During their first years in New York, many Yemenites lived in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, later moving to the Borough Park section of Brooklyn. Quite a few succeeded in saving enough for down payments to buy houses, representing a big step in their upward mobility. The significant improvement in their standard of living considerably changed the status and image of Yemenite women. Their traditional domestic roles gave way to additional functions. They were often employed outside their homes, many as seamstresses or in the service industry. Several attended night school to learn to read and write English. They had more opportunities for education and fulfillment in public life than any other contemporary Yemenite community in the world.

Bound together by their distinct ethnic customs, Yemenite men formed their traditional religious kanis while the women ventured into unprecedented charitable work. The international scope of activities of the Yemenite women’s group was remarkable. The Yemenite Ladies’ Relief Society was organized in the 1930s, less than a decade after their arrival during the major economic depression era in the United States. The impetus for the growth and development of American-style charities came about as a result of a severe famine that struck Southern Arabia and the persecution of Jews in many areas there. In addition, there were growing needs of several impoverished Yemenite Jewish communities in Palestine from the years preceding World War II until the 1950s, following the mass immigration. Previously stifled by male-dominated community structures and still overwhelmed, by economic hardships, these extraordinary newly literate Yemenite women made tremendous financial contributions to needy brethren while simultaneously elevating themselves to a remarkable level of organizational achievement compared with other newly arrived immigrants in New York.

The Yemenite Ladies’ Relief Society addressed a variety of philanthropic causes over the years. In New York their charitable organization paralleled, in principle only, their traditional social-communal work for the needy in Yemen. They created a network of women who collected funds for Yemeni poor and their health care, both in Yemen and Erez Israel. They organized dinner-dance fundraisers, monitored financial transactions, demanded reports from the receiving organizations abroad, and maintained a vast correspondence for this purpose. Yemenite women in America were therefore quite different from their counterparts elsewhere in the world, who had not yet attained this level of public activity. Their work was also similar in both ideology and fundraising methods to other American Jewish women’s voluntary organizations.

Within one decade of their arrival in the “goldene medinah” (golden land), the women led the vanguard in adaptation and acculturation in New York. They were the first to learn English and they immediately harnessed themselves to help earn their families’ livelihood. Indeed, the Yemenite Jewish women in New York were the agents of change in their community, while maintaining cultural traditions in the home.

Conclusion

Yemenite women proved to be most stable and resourceful, both in Yemen, where tradition reigned, and after immigration to Erez Israel and New York. They adapted to changing economic, social, and communal conditions, acculturated in language skills and organizational life, and were instrumental in bringing up their daughters and sons to successfully integrate into the new worlds. They fully accepted the changes, enjoying the freedom of movement, exalting in their literacy, and finding ways to manifest a special mixture of modernity and traditional Yemenite culture. The men, on the other hand, generally adhered to the strict tenets of their religious practices to express their Yemenite Jewish identity. Once the next generation relinquished those strict practices, male Yemenite identity became very much diluted.

Yemenite women maintained most of their cultural traditions. The Yemenite heritage in song, dance, cuisine, jewelry, and embroidery never ceased to be a source of pride and self-respect for the women. Thus they continued to express themselves in these areas despite the socio-economic changes in their lifestyle. Moreover, they reveled in such expression, integrated the folkloric ways into the larger Jewish cultural arena, excelled in them, and even became the spokespersons for Yemenite Jewry in international forums. Eventually, Yemenite Jewish women succeeded in incorporating their folklore into the overall evolving Israeli cultural identity.

However, the characteristics of Yemenite women are not represented only by their ability to use cultural traits as ethnic resources. From the early 1900s, they were an integral part of all the major trends in the modern Jewish experience. They were pioneers from the very beginning of the Zionist enterprise in Erez Israel, both in urban areas as well as in agricultural settlements. They were also part of the mass immigration of Jews to the United States that formed the most prosperous, philanthropic, and creative Jewish Diaspora in the twentieth century.

Being in the forefront of those turning points and cardinal events in Jewish history did not shield Yemenite women from suffering deep wounds. They were not part of the political leadership or in positions of national authority and their physical destiny was all too often in the hands of others. The women remembered the degrading attitudes and behavior towards them, or towards their ancestors in the early pioneering days. They knew of the theft of jewelry and other property as the exhausted women finally boarded the airplanes in Aden on the way to the Promised Land. Certainly, they could not forget the tragic disappearance, kidnapping, and death of some of their children in the 1950s.

Thus, the collective identity of contemporary Yemenite women is an amalgamation of the scars of past torments combined with immense Jewish national and ethnic pride.

English

Druyan, Nitza. “Yemenite Jewish Women—Between Tradition and Change.” In Pioneers and Homemakers: Women in Pre-State Israel, edited by D. Bernstein, 75–87. Albany, NY: State University of New York, 1992.

Druyan, Nitza, ed. Yemenite Jewish Women, an issue of Nashim, A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies and Gender Issues. Number 11: 5766/2006. (Studies on the multi faceted experiences of Yemenite Jewish Women)

Gilad, Lisa. Ginger and Salt, Yemeni Jewish Women in an Israeli Town. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1989.

Hebrew

Dahoh-HaLevi, Yoseph, ed. A Hymn for Yona: Studies of Yemenite Jewish Culture. Tel Aviv: 2004.

Gamliel, Tova. Aesthetics of sorrow: The wailing culture of Yemenite Jewish women. Jerusalem: 2010.

Gamlieli, Nissim B. Love of Yemen. Tel Aviv: 1979.

Kapheh, Joseph. Ways of Life in Yemen. Jerusalem: 1961.

Seri, Shalom, ed. Daughter of Yemen. Tel Aviv: undated. (Includes many articles on various aspects of the lives and images of Yemenite Jewish women)