Caribbean Islands and the Guianas

Women were among the earliest Jewish settlers in the Dutch and English Caribbean, where they engaged in public roles as healers, traders, and slave owners, despite living in patriarchal socieites. Having emerged from crypto-Jewish communities, Jewish women experienced a difficult process of “rejudaization,” during which much of their previous religious agency within the home was lost. However, their mastery over enslaved men and women empowered them in ways unavailable to their European counterparts. They also had clear paths toward public ritual expressions of Judaism in the Caribbean. Women of color, both identified and not-identified as Jewish, played a critical role in the continuity of Jews and Judaism throughout the Caribbean.

The Jewish Caribbean

After 1580, Iberian conversos—“New Christians” with Jewish ancestry—settled in communities throughout the Atlantic World and beyond, where they could openly identify as Jewish. Amsterdam emerged as the mother community for this so-called “Western Sephardi Diaspora.” Portuguese Jews themselves referred to their Diaspora as A Nação (The Nation), denoting a singular sense of ethnic identity that transcended state, imperial, and confessional boundaries. This Portuguese-speaking Jewish Diaspora included multiple satellite communities throughout Europe, such as Livorno, Venice, Bayonne, Hamburg, and London. These Diasporic networks further extended to the New World.

Portuguese-speaking Jews of the Americas first settled in Dutch-occupied Brazil (1630–1654), where they joined “rejudaized” conversos who had already been living there under prior Portuguese rule. The Jewish community of the port city Recife scattered when the Portuguese re-conquered Dutch Brazil in 1654. Most returned to Amsterdam. Some went on to Livorno in Italy. And some settled in the Dutch, English, and French Caribbean, as well as in North America.

The earliest Jewish settlements in the Caribbean during the 1650s and 1660s were found in Dutch Guyana, English Suriname (later Dutch), English Barbados, and French Martinique. Some Jews were attracted to these locations because of the burgeoning sugar industry, but most were propelled by poverty and the promise of greener pastures. Amsterdam Jews had attempted to secure favorable settlement charters in Dutch Curaçao since before the expulsion from Brazil. Curaçao would later become the largest Jewish community of the Caribbean. In 1655, the English captured Spanish Jamaica, opening that island to Jewish settlement. In the 1680s Suriname’s community grew rapidly as Jews were expelled from the French Caribbean, bolstering the populations of English Jamaica and Barbados.

The height of Jewish prosperity and growth in the Caribbean occurred during the eighteenth century. New communities blossomed on the smaller islands of Dutch St. Eustatius, English Nevis, and Danish St. Thomas in what is today the U.S. Virgin Islands. In the nineteenth century, the demographics of the Jewish Caribbean changed dramatically. Ashkenazi Jews, mostly from German lands, outnumbered entrenched Portuguese Jewish settlers. Sephardim from the crumbling Ottoman Empire also migrated in large numbers to the Americas, including the Caribbean, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Jews began to settle in the Spanish Caribbean—Panama, Venezuela, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad (later English), and Puerto Rico—in the mid-nineteenth century. These communities continued to grow well into the twentieth century. Some parts of the Caribbean, especially the Dominican Republic, were havens for Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust. But as Caribbean colonies transitioned toward their independence between the 1950s and 1970s, Jewish communities diminished in response to growing political violence. Jews continued to leave post-colonial Caribbean states during the 1980s and 1990s in search of more secure upward social mobility in North America and Western Europe. Today there are likely fewer than 800 openly identifying Jews in the Caribbean.

Women and the Origins of Caribbean Jewry

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish banned the migration of New Christians to the Americas, fearing that their presence might undermine efforts to convert indigenous populations. Unofficially, however, a number of conversos, both male and female, found their way to Spanish territories. Hundreds of these conversos—including some who were sincerely Catholic—were accused of harboring some form of crypto-Jewish practice by three American tribunals, in colonial Mexico, Peru, and in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia), which had jurisdiction over the Caribbean.

Before Portugal was annexed to Spain in 1580, it implemented an opposite policy regarding New Christian migration to the Americas by punitively exiling those accused of Judaizing, as well as other crimes, to Brazil (De Assis). Since women were already the most vulnerable to inquisitorial investigation, the majority of New Christians sent to Portuguese Brazil during the sixteenth century were women. Some of these conversas and their descendants likely later contributed to the growth of a Jewish community in the Dutch Brazilian port city of Recife between 1630 and 1654. As the Jewish community of Recife was the seed community for the entire Jewish Caribbean, the genesis of Caribbean Jewry is very much a story of pioneering women.

Relatively few Christian European women migrated voluntarily or as lone individuals to the colonial English or Dutch Caribbean during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Those who did were often the wives of military officers, sex workers, or coerced into migration by a metropolitan government. Jewish women, like other religious minorities, did not conform to this narrative. Often, poverty and the prospect of religious tolerance were more decisive factors determining Jewish migration than were mercantile concerns. As a result, Jews settled in the Caribbean with far more sustained family life and larger, more extended, family networks than the average European settler. Thus, in contrast to Christian European migrants, Jewish women were among the earliest settlers of the Caribbean, and they appear in roughly the same numbers as men in the earliest Jewish cemeteries throughout the English and Dutch Caribbean.

The Caribbean Women of A Nação

Portuguese Jewish women of “The Nation” experienced distinct socio-cultural challenges. As conversas they had been the principal curators of crypto-Jewish practices throughout the Iberian world. While it is unclear what exactly the practice of “crypto-Judaism” entailed, it was likely defined largely by domestic practices confined to the home, passed down from mother to daughter (Melammed). As these Portuguese women transitioned from being New Christians to New Jews, they lost much of their religious agency as they accommodated the patriarchy of openly Jewish communal life. This difficult process of “rejudaization” very much informed male perceptions of openly Jewish women in the Caribbean, as in other parts of the Portuguese Jewish Diaspora.

Portuguese Jewish men throughout Western Europe, North America, and the Caribbean imagined a singular set of feminine virtues associated with Portuguese Jewish women. Portuguese women were portrayed as exceptionally modest and chaste. The eighteenth-century Surinamese Jewish chronicler David Nassy wrote, for instance, that the Jewish women of Suriname set the highest examples of integrity and virtue among all the women in the colony (Nassy, 112). Similar sentiments are found in the Portuguese communal minutes of eighteenth-century Curaçao (Emmanuel and Emmanuel, 2:602). These male-imagined views often had the effect of ignoring, or even proscribing, women’s sexualities.

Portuguese women in the Caribbean were sometimes involved in sexual scandals in which they were more than passive participants. In these cases, in keeping with Portuguese Jewish ethno-social values, their class, rather than the nature of their transgression, often determined the extent and character of their condemnation (Ben-Ur and Roitman). Over the course of the eighteenth century, the communal board of Curaçao slowly, and subtly, also acknowledged that women were not simply the victims of male deception in cases of clandestine marriages (marriage without the consent of parents or clergy) that threatened the ethnic homogeneity of “The Nation,” but rather were in some cases also active and willing participants (Mirvis, 168–169) .

The Education and Social Mobility of Caribbean Jewish Women

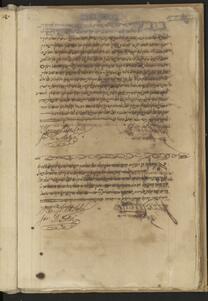

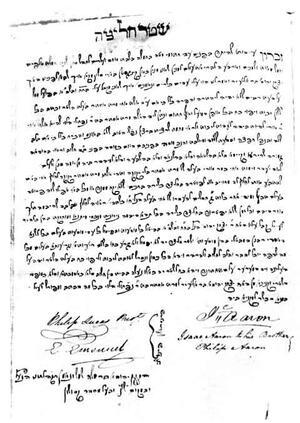

Halizah scroll 5584/1923. This document, which dissolves the commitment between a woman and her husband's brother to marry if the husband dies childless, was given to the bride by the groom's brother on the wedding day, because of Jamaican Jews' numerous and lengthy travels throughout the world.

Institution: Mordechai Arbell Collection, Diaspora Museum, Tel Aviv.

As in all other parts of the Jewish world, Portuguese Jewish fathers in the Caribbean held different educational expectations for their daughters and sons. Girls did not attend the primary Talmud Torah schools found throughout the Dutch and English Caribbean. Curaçao’s Jewish communal minutes from the eighteenth century, which are heavily focused on education, do not mention girls. Some wealthy fathers hired tutors for both their sons and their daughters. In a number of wills from eighteenth-century Jamaica, paternal testators specified that their elite daughters be instructed in the arts of sociability, such as dancing and music. In this, Caribbean Jews were following the example of their affluent Dutch and English counterparts.

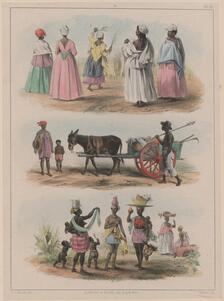

Some colonial-era Caribbean commentators, such as Edward Long in Jamaica and David Nassy in Suriname, believed that well-to-do white women born in the Caribbean—referred to as Creoles—were at an educational disadvantage because they grew up surrounded by enslaved attendants who lacked formal education. David Nassy complimented Portuguese Jewish parents for their efforts in sequestering their daughters from the cultural influences of enslaved attendants (Nassy, 155). Nassy’s view was perhaps more aspirational than realistic. In slave societies like Suriname, it was more common for Jewish women to communicate in Creole languages, spoken by the enslaved, than Jewish men (Vink, 64). Caribbean Jewish wills reveal as well that it was common for wealthy Jewish girls to grow up surrounded by personal slave attendants, who were often appointed to that role through testamentary bequests.

Jewish girls and young women had very limited opportunities for upward social mobility in the Caribbean. Every colonial-era Caribbean Jewish community supported an Aby Yetomim (Father of the Orphans) confraternity with a mandate to provide education to male orphans. As in Amsterdam, the Dutch Caribbean colonies of Suriname and Curaçao also supported female orphanage societies. No such institutions existed in the English Caribbean, although there were some abortive attempts to fill that need. The lack of female orphanage confraternities suggests that parentless Jewish girls in these areas likely labored in the homes of relatives or friends for their dowries. These vulnerable girls were often the victims of physical and emotional abuse, sexual exploitation, and rape. One very limited opportunity for female upward social mobility was application to the dowry lottery in Amsterdam, the santa companhia de dotar orphas e donzellas, available to both Jewish and conversa Portuguese girls anywhere in the Diaspora with the support of a male guarantor.

The Public Lives of Caribbean Jewish Women

It has been said about the public roles of women throughout the Portuguese Jewish Diaspora that “men kept their wives restrained, essentially as prisoners” (Bernfeld, 177), because of the persistence of Iberian patriarchal mentalities. Although this is to a large extent a faithful characterization of Portuguese Jewish society, it is far from the full story. Portuguese Jewish women engaged in clear public pursuits, but always within limits, and usually within the shadow of a male relative.

Women both Jewish and non-Jewish, were inextricable parts of local Caribbean economies. Women appear on tax records from eighteenth-century Kingston, Jamaica. Women were likewise listed among the property owners of numerous Caribbean towns. Many of those same women also owned property in Europe. Another indication of the strong presence of women within the Caribbean public sphere was their use of the press. Preemancipation-era Jewish women published advertisements in Caribbean periodicals with the same frequency as men. Among the most common types of advertisements were public announcements of runaway slaves.

Healing and medicine were public practices largely open to women and sometimes provided a path toward feminine public autonomy. At least 22 women interred in Surinamese Jewish cemeteries are identified on their tombstones as midwives (Ben-Ur and Frankel, 645). Jewish women healers throughout the Dutch and English Caribbean sometimes partnered with their physician husbands and took over their practices when they died. Hanah de Leon of St. Eustatius, the wife of the island’s principal Jewish physician, was described in Hebrew on her 1783 tombstone as a “skilled doctor and expert midwife” (rofa’ah baki’ah u-miyaledet mumḥit) (Hartog, 73). Similarly, in the early nineteenth century, Rebecca Dacosta Alverenga of Kingston, Jamaica, who had married into a family of Jewish physicians, carried on her deceased husband’s practice in partnership with their son.

It is often assumed that in the colonial Caribbean—as in other places—widowhood was the most concrete path for women to obtain public agency. While this was in some cases true, most Caribbean widows, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, became impoverished as a result of the loss of their husbands. In Jamaica, widows were the most common beneficiaries of social welfare (Mair, 36). While it was nearly impossible to deny a widow a portion of her husband’s estate, certain testamentary methods were often employed by men to limit their wives’ inheritance beyond the mandated one-third of their estate. At times, these limitations were extreme and could include women’s loss of custody over their own children. Despite these limitations, it has been argued that the individualism of the early Protestant Americas, possibly including the Caribbean, where men and women shared more equal roles in public religious observances, may have helped to engender a sense of greater feminine public agency in the Americas than in Europe (Snyder).

One common way for women to publicly express their ritual identities as Jews was through their testamentary piety, that is, through charitable and philanthropic donations to communal causes. One exceptional example is Judith Baruh Alvares (née Aguilar) of Port Royal, Jamaica, who was described in Hebrew on her 1732 tombstone as an “honorable, modest, charitable, woman of valor” (ha-khevodah, ha-ẓenu‘ah ve-ha-ẓadeket ’eshet ḥayil). Her communal donations in her will included a set of silver Torah scroll ornaments, honoraria to communal functionaries, elaborate donations to each of the islands three major synagogues, renovations to Hunt’s Bay cemetery, and bequests to each of the island’s Jewish confraternities.

Jewish Women Slave Owners

Jewish women were slave owners in the Caribbean. In some Jewish wills from the eighteenth century, wives and daughters inherited dozens of enslaved individuals. Jewish women testators also bequeathed their own slaves in their wills. Indeed, their mastery over enslaved African and African-descendent men and women empowered Caribbean Jews in ways unavailable to their counterparts in Europe. And Jewish women could be just as abusive to their slaves as their fathers and husbands. One late eighteenth-century English traveler in Suriname described a Jewish woman torturing and killing an enslaved woman in what was thought to be an act of jealousy (Stedman, 56). Indeed, there persists to this day a popular perception in Suriname of Jews as especially abusive slave owners, which in most accounts, casts the Jewish woman as the principal offender (Vink, 115, 120–21).

Enslaved individuals resisted their dehumanization, including by Jewish women. In one case from late-eighteenth-century Jamaica, an enslaved woman called Jenny was convicted by a slave court of poisoning the abusive Jewish lady of the house—a rather common accusation directed at household slaves (Mirvis, 84). It is clear that Jewish women, like Jewish men, showed no particularities in their patterns of slave ownership, which conformed in every way to the larger trends of the slave societies in which they lived.

Caribbean Jewish women also explored the exploitive sexual opportunities available to them in slave societies. That is, they engaged in sexual relationships with disenfranchised men and women of color—just as their male counterparts did, although these cases were rarely documented. In Suriname, where a few such cases are documented, offending white and Jewish women could be penalized with banishment, flogging, and branding for disrupting what was seen by white colonial elites as the “natural order.” The implicated black male was executed. This was the case with the young Surinamese Ashkenazi woman Ganna Levij (Hannah Levi), who was flogged in 1731 for having sex with a young enslaved man who was executed (Vink, 222).

Jewish Women of Color in the Caribbean

Enslaved women were sometimes more valued than enslaved men and were far more likely to be bequeathed than men. Women and girls made up 62 percent of the slaves bequeathed in eighteenth-century Jamaican Jewish wills (Mirvis, 83). Jewish and non-Jewish slave owners had possession over enslaved women’s bodies as well as their reproductive futures (“increase”), and women were more commonly found in the home as domestic labor, where they were often the victims of sexual and other forms of assault. Caribbean slave societies such as Suriname, Jamaica, and Barbados were relatively accepting—albeit unofficially—of sexual relationships with disenfranchised women of color. These relationships, born in inequality and violence, often resulted in non-legally recognized blended families.

Relationships between Jewish men and women of color included cases of rape, concubinage, and surrogacy. Children of color were often incorporated into both the Jewish family and the Jewish community. In Suriname, for instance, there were efforts on the part of male Jewish slave owners to convert their “Mulatto” children to Judaism. Over the course of the eighteenth century an increasing number of people of color throughout the Caribbean identified as Jewish. Jews of color in Suriname even asserted their own communal agency by forming a confraternity in the late eighteenth century called Darhe Jessarim (The Path of the Straight).

Jewish women of color played a fundamental role in the continuity of Jewish life throughout the Caribbean during the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, as communities eased discriminatory restrictions on their social inclusion (Ben-Ur, “A Matriarchal Matter”). As Caribbean Jewish communities became increasingly racially blended over time, women of color became some of the most definitive architects of distinctly Creole Caribbean Jewry as the curators of domestic Jewish practice.

Halakhic definitions of Jewishness, which focused on matrilineal descent, often did not factor into the self-identities of Jewish women of color in the Caribbean. And, not all Jews of color identified as such as a result of ancestry. In some cases, women of color converted to Judaism. For instance, the free “mulatto” woman of Jamaica known as Mary Blagrave converted to Judaism in the 1760s, taking the name Sarah Israel (Mirvis, 191). She lived with a legally married Jewish man David Aboab Furtado, with whom she had six children who had no legal right of inheritance. In name, however, her children were indistinguishable from other Jews on the island, as they were all known as Aboab Furtado. Furthermore, in David’s will, Sarah appeared to have the halakhic status of a concubine (pilegesh), in that she was given a portion of the estate and appointed as the executor, and her inheritance was conditional on her remaining single. Unlike David’s legal wife, Sarah had no right to one-third of David’s estate. In other instances, it is possible that Jewish men in the Caribbean relied on halakhic precedents allowing for the use of surrogate mothers—including black women (shifḥah kushit)—within the context of a childless marriage.

Jewish Women of the Modern Caribbean

As Jewish demographics in the Caribbean changed dramatically during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, gender ratios also sharply fluctuated. In the early nineteenth century, women made up the majority of Jews in Curaçao, as many unmarried men migrated to the Spanish Caribbean. Despite this female majority, it has been argued that Curaçao’s women still lacked opportunities for self-determination and that there persisted a high rate of female illiteracy (Capriles Goldish, 241–256). It is further believed that among the nineteenth-century female Jewish majority of Curaçao, most women remained unmarried. Some of the women who migrated from Curaçao to the burgeoning community of Danish St. Thomas in the early nineteenth century seemed to have found more opportunities for both economic freedom and intellectual expression (Capriles Goldish, 17–58).

During the years of the Holocaust, the Caribbean provided refuge to many Jews fleeing war-torn Europe. The British established displacement camps in both Trinidad and Jamaica that sheltered Jewish refugees. The dictator of the Dominican Republic, Raphael Trujillo, agreed in the 1838 Evian Accords to admit 10,000 Jews. This racially motivated decision, to encourage greater white migration, gave rise to the Jewish agricultural settlement of Sosúa. But the migration resulted more than double the number of Jewish men in Sosúa than Jewish women (Kaplan, 136). Some of the settlement’s leaders feared that the project would not survive without more women. In the end, the lack of a sustained female presence in Sosúa contributed to the ultimate disappearance of the Dominican Jewish enclave.

As Caribbean Jewish communities engaged with the trends of religious reform in the mid-nineteenth century, more opportunities became available to women to express their ritual lives publicly. In 1844, the moderate reformer Benjamin Cohen Carillon included both married and single women in his confirmation ceremony for community members of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands (Philipson). In January 1963, with the merger of Curaçao’s two Jewish communities, the new bylaws stipulated that women would no longer be seated separately from men during prayer and that they would be counted among the prayer quorum (Emmanuel and Emmanuel, 1:506–12). Similar rules were adopted in Jamaica in 1979. Today, women are leaders in liturgical synagogue practices, often functioning in place of rabbis or cantors in both Curaçao and Jamaica where there are still active communities.

In the late twentieth century, Caribbean Jewish women were the guardians and curators of the Jewish legacy of the region. When the Dutch anthropologist Eva Abraham Van Der Mark set out to study Jewish society in Curaçao, including issues of racial belonging, she relied on women as her key informants (Abraham-Van Der Mark). In Jamaica, Marilyn Delevente, one of the most prominent leaders of the Jewish community, also became one of its most important chroniclers, dedicating her voice to preserving the Jewish legacy of the Caribbean (Delevante). Today, women, including many women of color, are found in leadership roles throughout the remaining active Jewish communities and heritage sites of the Caribbean.

Abraham-Van Der Mark, Eva. “Marriage and Concubinage Among the Sephardic Merchant Elite of Curaçao.” In Women and Change in the Caribbean: A Pan-Caribbean Perspective, ed. Janet H. Momsen, 38-49. Kingston, JM and Bloomington, IN: Ian Randle Publishers and Indiana University Press.

Assis, Angelo Adriano Faria de. “Inquisição, religiosidade e transformações culturais: a sinagoga das mulheres e a sobrevivência do judaísmo feminino no Brasil colonial.” Revista Brasileira de História 22, no. 43 (2002): 47–66.

Ben-Ur, Aviva. “A Matriarchal Matter: Slavery, Conversion, and Upward Mobility in Suriname’s Jewish Community.” In Atlantic Diasporas: Jews, Conversos, and Crypto-Jews in the Age of Mercantilism, 1500–1800, eds. Richard L. Kagan and Philip D. Morgan, 152-169. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Ben-Ur, Aviva and Rachel Frankel. Remnant Stones: The Jewish Cemeteries of Suriname: Epitaphs. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2009.

Ben-Ur, Aviva and Jessica Roitman. “Adultery Here and There: Crossing Sexual Boundaries in the Dutch Jewish Atlantic.” In Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800, eds. Gert Oostindie and Jessica V. Roitman. Leiden, NL: Brill, 2014.

Bernfeld, Tirtsah Levie. “Sephardi Women in Holland’s Golden Age.” In Sephardi Family Life in the Early Modern Diaspora, ed. Julia R. Lieberman, 177–222. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press.

Capriles Goldish, Josette. Once Jews: Stories of Caribbean Sephardim. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2009.

Delevante, Marilyn. The Island of One People: An Account of the History of the Jews of Jamaica. Kingston, JM: Ian Randle Publishers, 2007.

Emmanuel, Isaac S. and Suzanne A. Emmanuel. History of the Jews of the Netherlands Antilles, 2 vols. Cincinnati, OH: American Jewish Archives, 1970.

Hartog, John. “The Honen Daliem Congregation of St. Eustatius.” The American Jewish Archives Journal 19, no. 1 (1967): 60–7

Kaplan, Marion A. Dominican Haven: The Jewish Refugee Settlement of Sosúa, 1940–1945. New York, NY: Museum of Jewish Heritage, 2008.

Mair, Lucille Mathurin. A Historical Study of Women in Jamaica, ed. Hilary Mcd. Beckles and Verene A. Shepherd. Kingston, JM: University of the West Indies Press, 2006.

Melammed, Renée Levine. Heretics or Daughters of Israel?: The Crypto-Jewish Women of Castile. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Mirvis, Stanley. The Jews of Eighteenth-Century Jamaica: A Testamentary History of a Diaspora in Transition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

Nassy, David. Historical Essay of the Colony of Suriname, eds. Jacob R. Marcus and Stanley F. Chyet. Cincinnati, OH: American Jewish Archives, 1974.

Philipson, David. “An Early Confirmation Certificate from the Island of St. Thomas, Danish West Indies.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 23 (1915): 180–182.

Snyder, Holly, “Queens of the Household: The Jewish Women of British America.” In Women in American Judaism: Historical Perspectives, ed. Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, 15-45. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2001.

Stedman, John G. Stedman’s Surinam: Life in Eighteenth-Century Slave Society, ed. Richard Price and Sally Price. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Vink, Wieke. Creole Jews: Negotiating Community in Colonial Suriname. Leiden, NL: KITLV Press, 2010.