Zionism in the United States

Jewish women constructed an approach to American Zionism that reflected their own unique position in American and Jewish society, employing the category of gender as a variable in the historical analysis of American Zionism. Jewish women were active participants in American Zionism from the earliest years of the movement. Zionist organizations for women, most prominently Hadassah, focused on creating study circles and engaged in participatory and grass-roots model of philanthropy to support Zionism. Throughout the movement, influential women moved fluidly between private and public life, and they placed areas of great concern to their own lives as American Jewish women onto the Zionist public and political agenda.

Background of American Zionist Movement

The modern movement of Zionism began in the nineteenth century and had as its goal the return of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel. Scholars have often noted that the cultural and political contexts of the United States shaped and informed the particular directions and boundaries of the American branch of the movement. American Zionism, unlike its European counterpart, tended to shun political activity, for the conditions that propelled political Zionism elsewhere—Jewish homelessness and persecution—did not apply to American Jews themselves. American Zionists never subscribed to the European Zionist emphasis on shelilat ha-golah [the negation of the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora]. Instead, American Zionism consistently portrayed the movement as faithful to democratic and social ideals and argued that the highest ideal of Zionism—social justice for the persecuted remnants of the Jewish people in Europe and elsewhere—was identical with the ethos that animated the American nation.

The American setting caused most early American Zionists to regard education and philanthropy and not immigration to The Land of IsraelErez Israel or Jewish statehood as the decisive Zionist acts, and through the influence of men such as Solomon Schechter and Mordecai Kaplan many also came to regard Zionism as a crucial bulwark against American Jewish assimilation.

Women in the American Zionist Movement

In these accounts of the American Zionist narrative, sufficient attention has seldom been paid to the distinctive roles occupied by women. However, novel ways for understanding and defining the nature of the American movement emerge through the adoption of a more inclusive approach that focuses upon the historical experiences of women as well as one that employs the category of gender—the socially and culturally constructed aspects of the divisions of the sexes—as a decisive variable in the historical analysis of American Zionism. For even as American Zionist women shared a common Jewish heritage with their fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons, they also constructed an approach to American Zionism that reflected their own unique position in American and Jewish society. A complex interplay of gender, social class, and religio-ethnic culture shaped the ways in which women helped to direct the course of Zionism in America, and a proper history must take all these factors into account in presenting developments and trends that marked the movement.

While scholars have frequently labeled mid-nineteenth-century European men such as Moses Hess and Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer as mevasserei ziyyon [forerunners of Zionism], the American Jewish poet and writer Emma Lazarus surely merits this appellation as well. Stirred to Jewish consciousness by the Russian pogroms of the early 1880s and the subsequent plight of Eastern European Jewry, the aristocratic Lazarus, whose familial roots in America extended back to the 1700s, called for the rebirth of the Jewish nation on its ancestral soil in both poetry and prose. In her 1882–1883 prose work “An Epistle to the Hebrews,” published in the American Hebrew, Lazarus promoted a proto-Zionist vision that predated and paralleled the Zionist position advanced a decade later in the writings of Theodor Herzl. Lazarus wrote, “What we need to-day … is the building up of our national, physical force. … For nearly nineteen hundred years we have been living on an idea. … Our body has become starved and emaciated beyond recognition. … Let our first care to-day be the re-establishment of our physical strength, the reconstruction of our national organism, so that in the future, where the respect due to us cannot be won by entreaty, it may be commanded, and where it cannot be commanded, it may be enforced.”

Rosa Sonnenschein, publisher and editor of the American Jewess between 1895 and 1899, echoed many of the Zionist themes that Lazarus had articulated and became one of the earliest supporters of Herzl on American soil. In the April 1897 issue of her journal, Sonnenschein wrote an article entitled “What Jew Has Not Dreamed of Seeing Israel Restored as a Nation—Of a New, Free, Great, and Glorious Judah?” Later that year, she was invited by Herzl to attend the First Zionist Congress in Basel as the representative of the American Jewess.

As Zionism began to attract a growing number of American adherents, the bulk of American Jewish women Zionists expressed their support of the nascent Zionist movement through organizations that were by and large—though not exclusively—segregated by gender. Shortly after the 1913 establishment of the American branch of the Orthodox Zionist organization Mizrachi, Orthodox Zionist women formed the Mizrachi Women’s Organization of America (today called AMIT) and sought to rebuild the Jewish homeland on the basis of traditional Orthodoxy, by serving “the physical, social, educational, and spiritual needs of refugee and native youth.” In 1926, American women committed to the cause and principles of Labor Zionism established Pioneer Women and attempted to “arouse public opinion on behalf of the rescue of our people” by advancing a humanitarian and “progressive social vision.” By engaging in these activities, the women in these organizations championed causes that were consonant with the image the larger society held of women as nurturers.

Hadassah

Foremost among all these groups was Hadassah. The goals and objectives of Hadassah were akin to those that animated the other groups, and an analysis of the methods and style that Hadassah women employed to achieve their organizational aims reveals the distinctive role that women’s organizations came to play in the unfolding and development of American Zionism. Hadassah had its origins in study circles organized by Emma Leon Gottheil, the wife of Richard Gottheil, an ardent Zionist and Columbia University professor of Semitics. Gottheil accompanied her husband to the Second Zionist Congress in 1898 and was charged by Herzl himself to organize American Jewish women on behalf of the Zionist cause. She responded by establishing chapters of the Daughters of Zion as an affiliate of the Federation of American Zionists. These study groups soon dotted the New York area and attracted to their ranks outstanding young women such as Jessie Ethel Sampter and Lotta Levensohn, who were destined in later decades to become prominent American Zionist figures. The women who participated in these study circles saw their devotion to Palestine and Zionism as a means of redress for the problems of social inequality that dominated the Progressive agenda and spirit of the time.

In 1907, the well-known and highly regarded Henrietta Szold became an active member of the Harlem study group known as Hadassah Circle. Szold traveled to Palestine in 1909. There she obtained a firsthand understanding of conditions in Erez Israel. Appalled by the lack of medical and sanitary facilities in the nascent and growing Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv [Jewish settlement], Szold resolved upon her return to the United States to alleviate the effects of disease, starvation, and homelessness that existed there by establishing health programs and facilities for Jews and Arabs alike. Though Szold served in 1910 as honorary secretary to the male-dominated American Federation of Zionists, that group’s financial chaos caused her to ignore it and to turn instead to women Zionists in Daughters of Zion and Hadassah study circles for support. A constitution for the Hadassah organization was drawn up in 1912. While formally affiliated with the Federation of American Zionists, Hadassah insisted upon maintaining control of its own affairs—much to the consternation of several male critics who found it inappropriate that women express their independence in this way.

Hadassah ignored these critics and built its programs and activities on a heritage of Jewish philanthropy as well as upon the charitable and organizational model provided by the U.S. women’s club movement of the Progressive Era. Chapters were soon formed throughout the United States, and memoirs authored by women throughout the country during these years testify to the universal success and status Hadassah enjoyed throughout the American Jewish community. Membership in Hadassah and participation in its projects and activities became a fixed part of the civic duties in which thousands of American Jewish women engaged.

With the financial support of Nathan and Lina Straus, Hadassah sought to offer preventive health care to Jewish settlers and natives alike by sending two nurses—Rose Kaplan and Rachel [Rae D.] Landy—to Palestine in 1912. Bertha Landsman, a public health nurse trained in New York, followed in the footsteps of Kaplan and Landy; she sought to reduce the soaring infant mortality rates that then obtained in Palestine by offering free layettes and pasteurized milk to parents who gave birth in Rothschild Hospital as well as by improving sanitary conditions at childbirth by educating midwives.

The success of these early endeavors caused the Federation of American Zionists to charge Hadassah in 1916 with responsibility for raising the then seemingly insurmountable sum of twenty-five thousand dollars for the creation of an American Zionist Medical Unit (AZMU) in Palestine. Undaunted by the challenge, Szold called on each Hadassah woman throughout the country to save on carfares and contribute fifteen cents in support of the project. Her fund-raising technique mobilized thousands of women on behalf of the Zionist enterprise, and Hadassah soon exceeded its goal by contributing thirty thousand dollars for the AZMU.

The participatory and grass-roots model of philanthropy established by this activity served as a model for the fund-raising projects of other organizations as well as for Hadassah itself. For example, Mizrachi Women held frequent luncheons where individuals offered small donations for the support of religious institutions and orphanages as well as children’s homes and religious A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim in Palestine. The Women’s League for Palestine, established in the early 1920s by Emma Gottheil, also utilized comparable fund-raising techniques for the creation of vocational schools and residences for young Jewish refugee women when they arrived in Palestine.

However, Hadassah retained its position as the preeminent organization of Zionist women in America throughout this entire period. In 1921–1922, Hadassah made an appeal to religious school pupils in the United States to “give a penny so a child in Jerusalem can eat.” By 1923, schools in Jerusalem were able to provide hot lunches for all their students. In the 1930s, Hadassah likewise garnered financial support for the Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah project designed to bring Jewish refugee children to Palestine by gathering its membership together in hundreds of weekly or monthly chapter tea or parlor meetings throughout the United States. At these meetings, each woman was asked to donate a few dollars until the chapter goal of $360 was achieved. In this way, Hadassah quickly reached its national goal of sixty thousand dollars. All of this reflects the central role women now occupied in American Zionism, and Hadassah became arguably the most powerful Zionist organization in the world by the 1930s.

The humanitarian and social concerns these organizations addressed were viewed as logical public extensions of traditional female domestic responsibilities, and through Hadassah and other groups women were allowed to take their skills and talents out of the home in a socially approved manner. Participants in these organizations eroded the boundaries between public and private domains by transforming issues originally of private concern into matters of societal import, in a particularly Jewish and political arena.

To be sure, such expansion did not receive universal approbation. From the outset, Hadassah had more than its share of male critics who were outraged by the independence it displayed. This attitude reached its zenith in 1926–1928, when Louis Lipsky, president of the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA), was enraged by the refusal of Hadassah and its president, Irma Levy Lindheim, to cosign a bank loan for the United Palestine Appeal of the ZOA. Lindheim publicly criticized the ZOA for what she regarded as its poor organization and fiscal irresponsibility, and she demanded increased Hadassah representation to the Congress of the ZOA. In response, Lipsky called for the National Board of the ZOA to rebuke Lindheim. The board rejected his request and even went so far as to express a vote of public confidence in Lindheim. Lipsky then turned to the pages of the Zionist journal New Palestine to attack Hadassah; he accused Lindheim of abandoning the principles of Henrietta Szold, “who recognized the proper role of women within the ranks of the ZOA.” Such gender-based critique caused Szold herself to respond, and she asserted that she saw nothing “unwomanly” in the positions Lindheim championed. Szold maintained that Hadassah had every right to play an independent role in Zionist affairs. In affirming their right to speak out autonomously on public issues, Lindheim and Szold expanded the range of appropriate public behavior for females. The entire affair testifies to the strength and power of Hadassah as well as the public role of authority conferred upon women in the American movement.

Women Leadership in American Zionist Circles

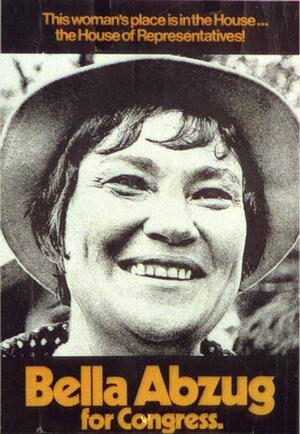

The poster reads "This woman's place is in the House...the House of Representatives! Bella Abzug for Congress."

Idealist and activist, champion of progressive causes, Bella Abzug ran for Congress in 1970 on a women’s rights/peace platform, and New York agreed that "this woman's place is in the House."

Courtesy of the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress.

So empowered, other women claimed positions of public responsibility and leadership within American Zionist circles. Minette Baum, trained at Jane Addams’s Hull House, served as president of the Fort Wayne Zionist District from 1919 to 1935, one of the first women in America to occupy such a position in a male-dominated Zionist organization. Others such as Lotta Levensohn and Jessie Sampter did not hesitate to defend publicly the institution of the kibbutz from the critiques of more conservative American men in the 1920s and 1930s who attacked it as a source of socialism and immorality. Indeed, Sampter, in the pages of New Palestine, boldly called for groups of American haluzim [pioneers] to make aliyah and join the pioneers already there in the formation of a new society based on equality, justice, and cooperation.

These women were animated by a dual Jewish-American heritage that was often informed and shaped by a specific feminine sensibility. Lindheim herself, the daughter of an affluent German-American Jewish anti-Zionist family, described the moment of her conversion to the Zionist cause in 1923 in the following way: “I am an American. … I am a Jew. … Instead of an enigma to myself, am I therefore not doubly blessed, doubly responsible? What better fulfillment than to take my place with those who have suffered for centuries for their beliefs? To share in rebuilding a national life in the land where our forefathers held that very concept of freedom, equality, brotherhood on which the greatness of America—my America?—is built? … In that moment, … Zionism reached out to me and took my hand.” Sampter expressed similar sentiments in her poetry, and other American Jewish women—both foreign- and native-born—shared their vision. Eastern European native Golda Meir, informed by the tenets and visions of Labor Zionism, left America to join Kibbutz Merhavyah in 1921. Twenty-five-year-old American-born Hannah Hoffman, the daughter of a New Jersey Conservative rabbi and a graduate of Smith College, traveled to Palestine in 1925 over the objections of her family and became a pioneer at Tel Joseph; when asked to explain what motivated her decision to become perhaps the first native American haluzah [female pioneer] in Palestine, she stated, “It was a question of youth, an American tradition, one hundred percent pure American tradition. I felt that I was a Pioneer. The early settlers went West to build up the country—I would go to Palestine. I see many things similar in the thoughts and traditions of America and Israel. Pioneerism and interest in the Bible influenced me to come to Palestine.”

By the 1930s, the integral role that women had come to occupy in American Zionism was assured. The impact Zionism had upon the lives of these women, young and old alike catapulted such women as Shoshana Cardin into positions of prominence in American Jewish life. The role these women had come to play in the life of the American movement is captured in the memoirs of former New York congresswoman Bella Abzug, who recalled that in 1932, “When I was twelve, I joined Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir [the Young Guard], a Zionist Youth Organization. From then on, I was an enthusiastic Zionist who dreamed of working in a kibbutz, helping to build a Jewish national home in what was then called Palestine. Dressed in brown uniforms and ties, my friends and I rode the subways and stood in the cold on street corners, collecting pennies for our cause. It was my first venture into political campaigning, and also my first experience as a leader.”

Jewish women were active participants in American Zionism from the earliest years of the movement on these shores. From the time of Emma Lazarus, women expressed the greatest yearnings of the movement, and others such as Hannah Hoffman and Jessie Sampter participated in and described the pioneering dimensions of the Zionist cause. These women moved fluidly between private and public life, and they placed areas of great concern to their own lives as American Jewish women onto the Zionist public and political agenda. Informed by Jewish and American values, and conscious of their place as women in society, they often made their greatest contributions to the Zionist cause through gender-specific Zionist organizations, and the political success they enjoyed through these organizations frequently allowed them to bend the public course of American Zionism to their wills and voices. At the same time, figures ranging from Henrietta Szold and Minette Baum through Mary Ann Stein, president of the New Israel Fund in the 1990s, occupied leadership positions in general Zionist organizations as well. The full story of how American women participated in and shaped the American contours of Zionism has yet to be told.