The Immigrant Experience in NYC, 1880-1920 (Module #1)

This module is intended for use before playing the game Jewish Time Jump: New York and can stand alone without the game. It provides context for the Jewish immigrant experience in that period and introduces students to the different types of characters they will be meeting during game play (workers, activists, and manufacturers, to name a few).

Jewish Time Jump: New York lesson plans and activities were developed in partnership with ConverJent: Games for Jewish Learning and made possible with generous support from the Covenant Foundation.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

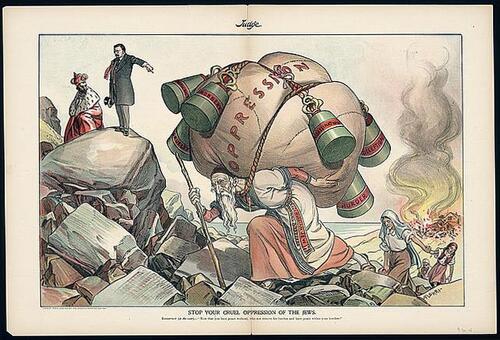

- Individuals flee countries of origin to escape social, economic, religious, and political oppression.

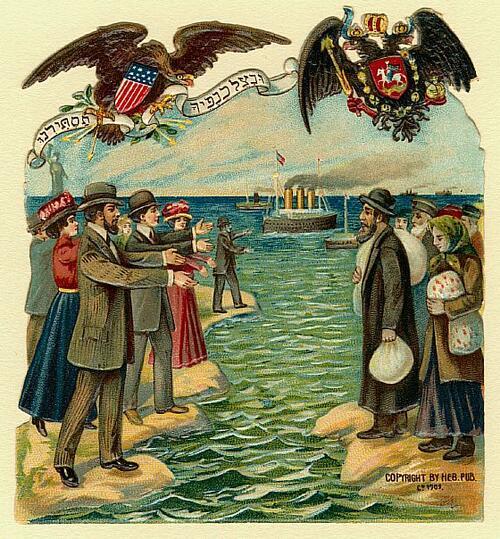

- While some immigrants were able to fulfill their dreams in America, others discovered that the opportunities they were searching for in the United States were not readily and equally available to all immigrants.

- Access to work and a sustainable income were essential for immigrants to lead happy, healthy lives.

Essential Questions

- What motivated Jewish immigrants to move from their home countries to the United States?

- What was it like to be a garment factory worker in early 20th century New York?

- What was it like to be a garment factory owner in early 20th century New York?

- How did employees’ and employers’ experiences differ from one another?

- How did some young immigrants’ experiences differ from the experiences of young Jews today?

- What aspects of work did immigrants find rewarding and what did they find challenging?

Notes to Teacher

Each section of the lesson outline includes instructions for alternate activities to help you adapt the material for students at different reading levels and groups of various sizes. If you have feedback—positive or constructive—after teaching this content, please let us know.

Some educators have requested a timeline of Jewish immigration to include with this activity. We recommend picking a few of the most relevant events from this era to share with your students. This timeline from the American Jewish Archives includes major waves of immigration as well as other important milestones. Another timeline, from the Library of Congress, shows American Jewish events alongside American and World events. Jewish Time Jump focuses on the years 1880–1920.

Handout: Observations and Impressions

Open this section in a new tab to print

This is a handout for teachers to use when teaching Jewish Time Jump: New York, Module 1. Photo Activity Worksheet Module 1 — The Immigrant Experience, Observations and Impressions.

Reflections: Writing Letters Home, The Immigrant Experience

Open this section in a new tab to print

This is a handout for teachers to use when teaching Jewish Time Jump: New York, Module 1.

Compare and Contrast: A Day in the Life of a Teenager, 1909 and 2014

Open this section in a new tab to print

This is a handout for teachers to use when teaching Jewish Time Jump: New York, Module 1.