Civil Disobedience: Freedom Rides

Discover the story of one young Jewish Freedom Rider and Gandhi's principles of civil disobedience, and prepare your own civil disobedience training video.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- Civil disobedience was an important tool of the Civil Rights Movement.

- "Ordinary" people can effect change.

Essential Questions

- What is civil disobedience and how was it practiced in the Civil Rights Movement?

- What led young people to participate in the Civil Rights Movements and what sacrifices did they make?

Materials Required

- Chalk board, white board, or chart paper

- Copies of Scenario Worksheet

- Gandhi's Rules of Civil Disobedience (ideally copied on the reverse side of the Scenario Worksheet)

- Copies of Document Study

- Excerpts from Boston Globe articles on Judy Frieze's experience as a Freedom Rider

- Scanned copy of one of the original Boston Globe articles on Judith Frieze's experience as a Freedom Rider (part 2 of 8)

- Optional: video camera

- Optional: computer with wireless access, speakers, and projector, or Smart Board

- Poster board or construction paper

- Art supplies

Notes to Teacher

This lesson plan centers on the story of one Jewish Freedom Rider, and includes articles and video of her story. If there are Freedom Riders living in your community, you may want to invite one of them to speak in your class or ask students to conduct video or audio interviews with them.

Civil Disobedience and the Freedom Rides: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy, Civil Rights, Unit 2, Lesson 3

One of the ways African American communities fought legal segregation was through direct action protests, such as boycotts, sit-ins, and mass civil disobedience. The tactic of non-violence civil disobedience in the Civil Rights Movement was deeply influenced by the model of Mohandas Gandhi, an Indian lawyer who became a spiritual leader and led a successful nonviolent resistance movement against British colonial power in India. Gandhi's approach of non-violent civil disobedience involved provoking authorities by breaking the law peacefully, to force those in power to acknowledge existing injustice and bring it to an end. For its followers, this strategy involved a willingness to suffer and sacrifice oneself.

In 1960, black college students used non-violent civil disobedience to fight against segregation in restaurants and other public places. On February 1, four black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat down at the whites-only lunch counter in Woolworth's and politely ordered some food. As expected, they were refused service, but they remained sitting at the counter until the store closed. The next day, they were joined by more than two dozen supporters. On day three, 63 of the 66 lunch counter seats were filled by students. By the end of the week, hundreds of black students and a few white supporters filled the lunch counters at Woolworth's and another store down the street.

The sit-ins attracted national attention, and city officials tried to end the confrontation by negotiating an end to the protests. But white community leaders were unwilling to change the segregation laws, so in April, students began the sit-ins again. After the mass arrest of student protestors on the charge of trespassing, the African American community organized a boycott of targeted stores. When the merchants felt the economic impact of the boycott, they relented, and on July 25, 1960, African Americans were served their first meal at Woolworth's.

The success of the Greensboro sit-ins led to a wave of similar protests across the South. More than 70,000 people – mostly black students, joined by some white allies – participated in sit-ins over the next year and a half, with more than 3,000 arrested for their actions.

Like the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides of 1961 were designed to provoke arrests, though in this case to prompt the Justice Department to enforce already existing laws banning segregation in interstate travel and terminal accommodations. These were not the first Freedom Rides. In 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), an organization devoted to interracial, nonviolent direct action led by the African American pacifist Bayard Rustin, co-sponsored a bus ride through the South with the Christian pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation, to test compliance with 1946 Morgan v. Virginia decision that prohibited segregation on interstate buses. Those first Freedom Riders were arrested in North Carolina when they refused to leave the bus. In 1961, James Farmer – one of CORE's founders and its national director – decided to hold another interracial Freedom Ride, with support from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (founded in 1957 by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, founded in 1909).

The Freedom Ride began in Washington DC in May, with two interracial groups traveling on public buses headed toward Alabama and Mississippi. (John Lewis, who appears in Unit 2 lesson 7 and Unit 3 lesson 5, was among those on the first buses of Freedom Riders.) They faced only isolated harassment until they reached Anniston, Alabama, where an angry mob attacked one bus, breaking windows, slashing its tires, and throwing a firebomb through the window. The mob violently beat the Freedom Riders with iron bars and clubs while the bus burned. The second bus was also brutally attacked in Anniston. Violence followed both buses to Birmingham, where a mob beat the Freedom Riders while the police and the FBI watched and did nothing. No bus would take the remaining Freedom Riders on to Montgomery, so they flew to New Orleans on a special flight arranged by the Justice Department.

The CORE-sponsored Freedom Ride disbanded, but SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, founded in 1960) took up the project, gathering new volunteers to continue the rides. A new group of Freedom Riders, students from Nashville led by Diane Nash -- a young African American woman -- gathered in Birmingham and departed for Montgomery on May 20. The Montgomery bus station, which initially seemed deserted, filled with a huge mob when the passengers got off the bus. Several Freedom Riders were severely injured, as were journalists and observers. The mob violence and indifference of the Alabama police attracted negative international press for the Kennedy Administration. In response, Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent 400 U.S. marshals to prevent further mob violence, and called for a cooling off period, but civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King, James Farmer and SNCC leaders insisted that the Freedom Rides would continue. So Robert Kennedy brokered a compromise agreement: if the Freedom Riders were allowed to pass safely through Mississippi, the federal government would not interfere with their arrest in Jackson.

At this point, the Freedom Riders developed a new strategy: fill the jails. They called on civil rights activists to join them on the Freedom Rides, and buses from all over the country headed South carrying activists committed to challenging segregation. Over the course of the summer, more than 300 Freedom Riders were arrested in Jackson, where they refused bail and instead filled the jails, often facing beatings, harassment, and deplorable conditions. More than half of the white Freedom Riders were Jewish.

Judith Frieze, a recent graduate of Smith College, was among those white northerners and many Jews who joined the Freedom Rides in the summer of 1961. Arrested in Jackson, she spent six weeks in a maximum security prison. Upon her release, she documented her experience in an 8-part series of articles published in the Boston Globe.

Eventually, the Freedom Rides succeeded in their mission: by the end of 1962, the Justice Department pressed the Interstate Commerce Commission to issue clear rules prohibiting segregation in interstate travel. The experience revealed the hesitancy of the federal government to enforce the law of the land and the intransigence of white resistance to desegregation. But it also strengthened SNCC, whose leadership at a crucial moment of the Freedom Rides led to the project's success and taught these young civil rights activists about the central role of politics, and the importance of appealing to the pragmatism of politicians -- even the President -- in the fight for civil rights.

Introduction: Civil Disobedience

- Write the words "Civil Disobedience" on the chalk board, white board, or a piece of chart paper.

- Distribute copies of the Scenario Worksheet to your students. Have a couple of students read the scenarios out loud. When all three scenarios have been shared, ask your students:

- Which of these scenarios is an example of civil disobedience?

- Once the correct scenario has been chosen, ask your students: Based on this example, how would you define civil disobedience? Write the responses on the chalk board, white board, or a piece of chart paper under the words "Civil Disobedience." After as many students have had a chance to respond as possible, add anything to the class definition that you feel may be missing.

- Explain that civil disobedience, as a philosophy, was first described and used by Henry David Thoreau in America in 1849. Since then it has been used by those fighting for their rights and national independence throughout the world. A few examples include: Mahatma Gandhi's fight for Indian independence from Great Britain and the fight to end Apartheid in South Africa. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a proponent of civil disobedience, and it was used throughout the American Civil Rights Movement. Emphasize that non-violence was a central component of civil disobedience and a challenging one for civil rights activists, who were often brutally attacked and beaten.

- Have your students turn over their Scenario Worksheet and review together [lightbox:11802]Gandhi's Rules for Civil Disobedience[/lightbox]. Explain that Gandhi developed certain rules of civil disobedience during his fight for Indian independence. Civil disobedience as practiced by King and his followers followed similar rules.

- Ask your students:

- What are some examples of civil disobedience from the Civil Rights Movement?

(Possible responses might include: sit-ins at lunch counters, refusing to move from a seat in the white section/black section of a bus, a peaceful march, a bus boycott, etc.) You may want to write your students' responses on the chalk board, white board, or chart paper. - How do you think you might respond if you were participating in an act of civil disobedience and someone taunted or cursed you?

- How do you think you might respond if you were participating in an act of civil disobedience and someone attacked you physically?

- What issues would you be willing to engage in civil disobedience for?

- What are some examples of civil disobedience from the Civil Rights Movement?

- Explain that responding to violence with non-violence required a lot of training and self-discipline.

Document Study: Judith Frieze, Freedom Rider

- Tell your students:

Today we're going to learn about a young woman, just a few years older than you, who took part in the civil disobedience of the Civil Rights Movement by volunteering for a project called the Freedom Rides. - Distribute copies of the Document Study to your students. Have a student read the introductory paragraph about Judith Frieze and the Freedom Rides. You may also want to review some of the information from the introductory essay with your students, so that they understand the context for Frieze's stories. Be sure to define any terms your students may not be familiar with.

- Break your class into small groups and have them read the excerpts from The Boston Globe on Document Study #1 out loud. Each group should choose one of Frieze's statements that stands out to them as being the most significant part of her experience.

- Have your students come back together as a class and share the statements they chose.

- Using the questions on the Document Study, discuss The Boston Globe articles with your students.

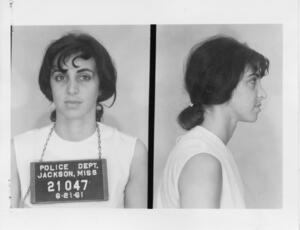

- While you're discussing the articles, you may want to project the "mug shot" taken of Judith Frieze when she was arrested during the Freedom Ride, which appears at the beginning of this lesson.

- Let your students know that Judith Frieze – now Judith Frieze Wright – told JWA in a 2010 conversation about the Boston Globe articles that she was not happy with the articles when they came out – she felt they were too "fluffy," highlighting details like conditions in the prison rather than the important civil rights issues at stake. Frieze later returned South to work for a year as a civil rights activist.

- Optional: Play the video clip of Judith Frieze Wright. Introduce the video by explaining: The Jewish Women's Archive (the creators of this lesson) invited Judith Frieze Wright to be interviewed at their 2010 Institute for Educators. We're going to watch a portion of that interview in which she reflects back on her experience as a Freedom Rider, from the perspective of 49 years later.

- After watching the video as a class, ask students to turn to the person next to them to talk about what they thought of Wright’s reflections, using the provided discussion questions as a guide.

Civil Disobedience Training Video

- This activity is designed as an in-class video project. If you do not have access to video equipment, the activity may also be done as a series of skits presented at the end of class.

- Remind your students that in The Boston Globe articles, Judith Frieze talks about certain things the volunteers were told in preparation for their Freedom Ride; this included what to do if they were met by an angry mob, what would happen if they were arrested, and how to carry out civil disobedience. Other activists have described similar "training" before an event, which often included a review of civil disobedience philosophy and rules as well as practical advice, such as "I don't want to be killed because you decided to throw a brick."

- Explain that in the 1960s, civil rights "training" was informal and done in person. In our modern, tech-savvy world, such "training" might involve a "training video" prepared by professional civil disobedience instructors. Today, our class is going to make such a "training video."

- In order to make the "video," take your students through the following steps:

- As a class, choose a type of civil disobedience action (you may want to refer to the list of examples from the beginning of class).

- Break your class into small groups. Each group will be responsible for developing and acting out a section of the video. Sections might include: Titles (responsible for checking with the different groups and developing appropriate title signs); The reason for our action (choose the cause you're fighting for. It could be something in your local news. You could make a list as a class and then vote on a cause. Your cause may also become obvious as you choose a type of civil disobedience action); Civil Disobedience rules and philosophy; What to expect at the action; What to expect if you're arrested (the arrest experience and time in prison); Reflections by activists from previous events. (Depending on your class size and time, you may want to add sections, delete sections, or combine sections.)

- Instruct your students to use the information gathered from the Introduction and Text Study to develop their section of the video. Provide time for the groups to develop their ideas and practice their part of the "training video."

- If you have access to video equipment, film each group individually, and show the whole video at the end of class or at the beginning of the next class. OR If you do not have access to video equipment, have all the groups perform their "skits" for the rest of the class.

Optional Assignment: Personal Sacrifice

- This assignment can be done in the classroom or as a homework assignment.

- Have your students write a 1-2 page essay describing ideals in their world that they feel are so important they would be willing to make the kinds of sacrifices that Judith Frieze and other Freedom Riders made (i.e. getting arrested, temporary loss of freedom to come and go as they please, or doing with less food, money, luxuries.)

- When the essays are done, you may want to have a few students read theirs out loud or post some on a bulletin board in your classroom or a school corridor.

Excerpts from Judith Frieze articles on Freedom Ride to Jackson, MS

Context

In 1961, Judith Frieze, a recent graduate of Smith College, joined African American and white volunteers on a Freedom Ride to Jackson, Mississippi. Their purpose was to test Boynton v. Virginia, a Supreme Court case ordering the integration of restaurants and waiting rooms in bus terminals serving interstate bus routes. Frieze was arrested and held in jail for six weeks for her act of conscience, as were many Freedom Riders. After her release, The Boston Globe ran a series of articles, written in Frieze’s voice by a reporter who had interviewed her. Below are excerpts from those articles, grouped thematically rather than presented in the order they were printed. (The themes at the top of each section were added by the Jewish Women’s Archive.) Note that some of the text in the original articles was printed in bold type, and has been reproduced that way below.

Excerpts from the Boston Globe series "The Judith Frieze Story"

Purpose of Judith Frieze's participation in the Freedom Rides

PURPOSE:

All of a sudden I was tired of talking. I had reached the point when I wanted to do something about this. I felt like the only way that I could make my principles meaningful was by involving myself.

It seemed necessary to close that gap between what I was saying and what I was doing.

I wrote to CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and volunteered to participate in a Freedom Ride.

- Boston Globe, July 30, 1961

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “My Ordeal in Dixie Penitentiary,” Boston Globe, 30 July 1961, p.1.

Preparation for Judith Frieze's participation in the Freedom Rides

PREPARATION:

There were nine of us on that Freedom Ride – three white girls and one white man, one Negro woman and four Negro men…

A Negro boxer from Chicago was with us. It often amazed me that he, a fighter, could maintain the non-violent behavior of a Freedom Rider.

- Boston Globe, July 30, 1961

We were not supposed to strike back if we were attacked.

The men were told to form a ring around the women, and we were instructed to try and protect Mr. Schwartzchild.

The crowd is most likely to be angry with a white man, Wyatt said.

Secondly, they would vent their feelings against the Negro man.

We white girls were the least likely to be attacked.

- Boston Globe, July 31, 1961

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “My Ordeal in Dixie Penitentiary,” Boston Globe, 30 July 1961, p.1.

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “The Came the Moment I’d Feared,” Boston Globe, 31 July 1961, p. 1.

The "Crime"

THE "CRIME":

The arrest of Miss Frieze and her eight companions brought to 140 the number of arrests during the 29-day siege of Jackson. The nine new riders were ordered arrested by Capt J.L. Ray after they entered the all-white waiting room and then failed to obey officers’ orders to move on. The only white man in the group, Henry Schwarzchild of Chicago, asked for permission to get a cup of coffee in the lunchroom and Ray told him to move on.

“I believe I have a right to get a cup of coffee,” Schwarzchild replied, and Ray told him that he was under arrest. Less than 10 minutes later the terminal was cleared of the nine riders.

- Boston Globe, July 22, 1961

“Then you are all under arrest,” he said.

A wave of relief spread over me.

I had looked forward to, and yet feared, this

moment. At last it had come and I was glad.

The police officers took our names and we were taken to city jail.

We had our moment of triumph, however, for we integrated the patrol wagon on the way – our whole group traveled together.

- Boston Globe, July 31, 1961

"Newton Girl Jailed in Mississippi with Eight Freedom Riders", Boston Globe, 22 June, 1961, p. 24.

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “The Came the Moment I’d Feared,” Boston Globe, 31 July 1961, p. 1.

Judith Frieze's experience in prison

PRISON LIFE:

My home for the next three days was a cubicle, approximately 13 feet by 15 feet. It was meant to house four prisoners. There were 20 of us….

Although there was a shower in the back of the cell and we could shower every day, I felt dirty every minute I was there.

We each received a clean sheet as we entered the cell, and that was all.

The linen was grey with filth, outmatched, perhaps, only by the mattress.

And there were plenty of them. The cell had four cots in it, each topped with a scrawny, filthy mattress. We put the three largest girls on three of the cots and two of the little girls on the

remaining one.

The rest of us—the 15 medium-size girls—slept on mattresses on the floor. We lined them up, side by side, and allotted two mattresses to every three people.

- Boston Globe, July 31, 1961

The food was horrible…

A typical breakfast in a Southern prison consisted of black, watery coffee, biscuits and molasses, and always grits – a dish which my Southern friends told me was ordinarily quite tasty, but prison style, it was horrible…

Lunch and supper were usually quite similar, only supper was colder.

We had beans – every imaginable variety – crumbly corn bread and tap water, if we were thirsty.

- Boston Globe, August 1, 1961

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “The Came the Moment I’d Feared,” Boston Globe, 31 July 1961, p. 1.

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “My Diary Eluded the Jailers,” Boston Globe, 1 August 1961, p. 1.

The Freedom Riders community in Hinds County Jail

PRISON LIFE - COMMUNITY:

The days in Hinds County Jail passed quickly, for we had devised ways to keep ourselves busy.

Each morning one of my cellmates gave ballet lessons. She had been a ballerina before going on the Freedom Ride…

We had mental exercise, too, in those early prison days.

Elizabeth Wyckoff, or Betty, as we called her, gave us Greek lessons during the day. She had been a classics professor at Bryn Mawr and Mount Holyoke Colleges.

We spent most of our time, however, getting to know each other.

At first we knew our new Negro friends by voice only. We had no way of seeing them. [They were in other cells since the jail was segregated.]

But dipping into our pool of contraband articles, we came up with a compact mirror. Now we could see each other. By holding the mirror out in the hallway between the two cells, those in one cell could see into the next.

In this way, we were able to “introduce” ourselves to each other.

- Boston Globe, August 2, 1961

Each evening we would “broadcast” a radio program.

One girl would play the role of announcer, another was in charge of commercials – we advertised those items found necessary around the cell, like toothpowder and “super-fatted lanolated soap.” The rest of us would deliver news bulletins, sing, tell jokes or act out original skits.

Most of the talent was amateurish, but several of the girls had excellent voices and we enjoyed listening to them.

- Boston Globe, August 5, 1961

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “Success Gave Us Courage to Endure Jail,” Boston Globe, 2 August 1961, p. 8

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “’Hate Letters’ Accuse Us, Jailers Intimidate Us,” Boston Globe, August 5 1961, p.8.

Judith Frieze reflects on her Freedom Ride experiences

ON REFLECTION:

[On July 23, 1961, Judith Frieze was bonded out of prison due to ill health. In the last of the Boston Globe articles, she reflects on her experience.] Now that I have the time to think about my past month, I have thied ta [sic] analyze the lessons I have learned.

There has never been any question as to whether the ordeal was worth it. I believed in a cause—integration—and I have done something about my belief. I have tried to make my beliefs meaningful; I have not merely talked about them.

I endured my prison sentence, and found it almost bearable because I was fighting for a cause in which I believed. And others were fighting with me.

- Boston Globe, August 6, 1961

Judith Frieze as told to Lois Daniels, “But Segregation’s My Business, Too,” Boston Globe, 6 August 1961, p. 8.

Discussion Questions

- Review who wrote these articles and when. For what purpose and what audience did she write them?

- What happened to Judith Frieze and the other volunteers during Freedom Ride? (Describe it in your own words.)

- What are Judith's stated reasons for taking part in the Freedom Ride? What do you think may have been some of Judith's unstated reasons for taking part in the Freedom Ride?

- What kind of preparation did the Freedom Riders get before taking part in this event? Why do you think such preparation was provided? Are there other kinds of preparations that you think might have been helpful, given what we know about Judith Frieze's experiences?

- Reread section B above. What do you think of the ranking – 1) white man, 2) black man, 3) white woman – as the most likely order for violent attack? Why do you think this would be true?

- How difficult and/or easy do you think Judith Frieze found non-violence or civil disobedience? What evidence do you have? How do you think you might have reacted if you had been in Judith's shoes?

- Based on these excerpts, what was life like in prison for Judith Frieze and the other female Freedom Riders? What sacrifices did they make? What do you think they gained? (for themselves, for others) How did they form a community?

- In the last of The Boston Globe articles, Judith Frieze says, "I endured my prison sentence, and found it almost bearable because I was fighting for a cause in which I believed. And others were fighting with me." How do group acts of civil disobedience like Freedom Ride differ from moments of personal resistance? What role do you think community played in activists' motivation for getting involved and ability to stay committed throughout the Civil Rights Movement?

- We know that Judith Frieze was Jewish. Although she does not mention any Jewish values as motivation for what she did, can you think of any that might fit this situation? Do you think it's significant that she does not mention her Jewishness in any way in relation to this event? Why or why not? What role does your Jewish identity play in the issues you're concerned about or act upon?

Front page story

A number of the Boston Globe articles about Judith Frieze's experience as a Freedom Rider were front page stories, including "Then Came the Moment I Feared," which can be seen in this newspaper clipping scanned from the microfilm. Frieze describes her arrest in this article (part II of the series).

Interview with Judith Frieze Wright

Context

In this video clip from July 2010, Judith Frieze Wright reflects back on her experience as a Freedom Rider in the summer of July 1961 and why she got involved with the Civil Rights Movement. Wright was interviewed by Oral Historian Jayne Guberman as part of JWA's 2010 Institute for Educators.

Judith Frieze Wright Interview, July 27, 2010

Judith Frieze Wright discusses her participation in the the Civil Rights Movement in an excerpt of an interview with Jayne Guberman, part of JWA's Institute for Educators, July 27, 2010.

Courtesy of Lynn Weissman.

Video Dicussion Questions

- What, if any, differences did you notice in how Judith Frieze Wright described her experience as a Freedom Rider in the video versus in the articles written at the time?

- Wright says that it was not only her commitment to justice that drove her to join the Freedom Rides, but also her desire for adventure. What do you think about that statement?

- Were there any other comments in the video clip that stood out to you? Which one(s) and why?

Scenario Worksheet

Scenario #1

Bob was laid off from his job several months ago when business fell off and his employer felt the need to cut back on their staffing. He, his wife, and two children have depleted their savings. Although Bob is getting some money from unemployment, it is not enough to pay his rent and provide food for his family. One day, after being turned down for yet another job, Bob passes a house where he notices that the front door is not completely closed. There are no cars in the driveway and it appears as if no one is home. Looking around to make sure that no one sees him, Bob slips into the house. Once inside, he is able to locate a few small valuable items including: cash, some jewelry, an mp3 player, and a laptop computer. He stashes these items in the backpack he is carrying and leaves. He hopes that he can get cash for them at the pawn broker's shop in his neighborhood.

Scenario #2

Sally is a sophomore at City University, which is a short subway ride from her house. She feels fortunate that she can attend this quality institution for a cost that she and her parents can afford, and has dreams of graduating and getting a good paying job in the field she's studying. Recently though, the administration has been talking about raising tuition by several thousand dollars. Sally knows that she and many of her friends would no longer be able to afford to go to City University if this happens, and that might mean the end of their dreams for the future. That's why Sally is joining a group of students who are going to go and sit in the Dean's office until the Dean and other administration officials will listen to the students' concerns. About 150 students show up and sit on the floor, on chairs, even on the tops of desks, making it pretty much impossible for the Dean and his staff to get any work done. The students are asked to leave, but they keep sitting quietly where they are. Finally, campus security is called, and Sally and her friends are dragged out of the Dean's office and arrested. Sally isn't happy about having a police record, but she believes that it was important for City University's administration to know how the students felt about the proposed changes.

Scenario #3

Sarah just graduated from college, and knows a number of young men who have gone off to fight in her country's war overseas. She hates to think of them being injured or killed at war, especially since it's a war that she believes her country should never have gotten involved in. Other people in her city feel the same way and have organized a march through downtown and past some government buildings. The march starts out calmly, with the anti-war protesters chanting some slogans and carrying signs. As the anti-war protesters pass their half-way point, some on-lookers begin yelling at them, calling them unpatriotic, and cursing them. Then one of the marchers picks up a stone and throws it at the on-lookers. Soon bottles, rocks, and punches are being thrown. By the time the police break up the rally, some people need to be sent to the hospital, some people are arrested, and local business owners are cleaning up broken glass from their stores.

Gandhi's Rules of Civil Disobedience

- Harbor no anger, but suffer the anger of the opponent.

- Do not submit to any order given in anger, even though severe punishment is threatened for disobeying.

- Refrain from insults and swearing.

- Protect opponents from insult or attack, even at the risk of life.

- Do not resist arrest nor the attachment of property, unless holding property as a trustee.

- Refuse to surrender any property held in trust at the risk of life.

- If taken prisoner, behave in an exemplary manner.

- As a member of the satyagraha (civil disobedience) unit, obey the orders of satyagraha leaders, and resign from the unit in the event of serious disagreement.

Gandhi’s Code of Discipline. www.uwosh.edu/faculty_staff/barnhill/ES_375/gandhi_rules.html. July 29, 2009

CORE

The Congress of Racial Equality was founded in 1942 and played a major role in the Civil Rights Movement, organizing many projects including Freedom Ride and Freedom Summer. CORE focused on interracial, nonviolent direct action.

SNCC

(Pronounced "snick") The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was founded at Shaw University in North Carolina in 1960. SNCC played a major role in the Civil Rights Movement, organizing and participating in many projects including Freedom Ride, Freedom Summer, and the March on Washington. SNCC focused on issues including desegregation of public facilities and voter registration using techniques of grassroots organizing and civil disobedience.

Civil Disobedience

The refusal to obey the laws, commands, or demands of a government or occupying power without using violence. It is usually a means to change unjust laws, rules or practices. The philosophy of civil disobedience was first outlined by Henry David Thoreau in an essay of the same name in 1849. Since then it has been used the world over.

Freedom Ride

During the summer of 1961, CORE and SNCC organized African American and White volunteers, mostly college students, to ride buses from the North into the South to test Boynton v. Virginia, a 1960 Supreme Court case that called for the desegregation of bus terminals served by interstate bus routes, which was not being enforced. The "Freedom Riders," as they were called, sat together – blacks and whites – on buses and, when they arrived at the segregated bus terminals, tried to desegregate them by sitting in mixed-race groups in the waiting rooms. They often faced angry, violent mobs in the bus stations. Approximately 2/3 of the white Freedom Ride volunteers were Jewish. These rides put enough pressure on the Interstate Commerce Commission that by September 1961 they were working on complying with Boynton vs. Virginia, which ruled that racial segregation on public transportation was illegal.

Electronic Archives of the Sovereignty Commission, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The Electronic Archives of the Sovereignty Commission, Mississippi Department of Archives and History: mdah.state.ms.us/arrec/digital_archives/sovcom/. An extensive online collection of photographs and other documents from Mississippi's official counter civil rights agency, 1956-1973. Browse the photography collection (scroll down), use the keyword search, or enter the name of a freedom rider to find his/her mug shot, articles that mention that individual, and any other related materials.

Freedom Riders, a film by Stanley Nelson

Freedom Riders, a PBS American Experience documentary by Stanley Nelson, features extensive archival photographs and footage as well as recent interviews with riders, government officials, and journalists. It focuses on the leaders of the Freedom Rides, who faced tremendous violence, including the bombing of one of the first buses and brutal mob attacks. The trailer and excerpts from the film are available on the film's website at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/freedomriders/watch. The film will premiere on PBS in May 2011. (More about the film and interviews with the filmmaker and two Freedom Riders can be found in a video segment from Democracy Now.) Facing History and Ourselves has developed a study guide for the film, which you can download at http://www.facinghistory.org/freedomriders.

Mississippi Freedom 50th

The website of the Mississippi Freedom 50th, a weeklong series of events to mark the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, features a post about a Jewish Freedom Rider, Henry Schwarzschild, who in quoted describing how his Jewishness motivated his participation. The website also includes a video trailer that provides an overview of the Freeom Rides.

Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. A thorough study of the Freedom Rides.

Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders

Etheridge, Eric. Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders. Atlas, 2008. A coffee table size book containing large images of Freedom Rider mugshots as well as recent photographs of select riders.

The King Center - Kingian Principles of Nonviolence

Kingian Principles of Nonviolence from The King Center, dedicated to the advancement of the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Judy and her husband Frank 'Sib" are wonderful people, my family and I am very blessed to have met them back in 1964 during the civil right era and we will always be eternally graful to them!!

I used the PBS film on Freedom Riders for this lesson. The segment titled "The Strategy" was particularly helpful. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americ...

I feel like we are missing something in this lesson. What do we do when you feel the "laws " such as segregation are wrong. How far are the students willing to go to right a wrong. This is a good lesson to teach about bystanders. Research shows that individuals are less likely to step up..civil disobedience ..when they are in a group than when they are by themselves for they feel someone else will step up. I would like to see some emphasis on " doing the right thing" even when others do not. There are written laws such as segregation and there are unwritten laws of segregation such as bullying.

It is important to stress what life was like then and not to make judgements based on our experiences of 2012. Today, it is not unusual for kids to talk back to parents, teachers or any authority. Back then, it was not acceptable to speak up r even travel alone as a woman.