De facto segregation in the North: Skipwith vs. NYC Board of Education

Investigate the dynamics of segregation in northern schools through a New York City court case ruled on by Judge and Jewish activist Justine Wise Polier.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- Though not written into law as explicitly as in the South, the Northern states of the US also experienced segregation and conflicts over civil rights.

- The court system was an important civil rights battleground.

- Education is a central civil rights issue.

Essential Questions

- What is de facto segregation and where has/does it exist?

- What were the civil rights issues of the North?

- What were some of the central civil rights court cases?

- Who was Justine Wise Polier and what was her role in the Civil Rights Movement?

Materials Required

- Court Timeline Cards (Handouts)

Prior to class, copy the Court Timeline Cards onto card stock and cut them out. If possible, laminate them so you can reuse them in the future. - Yarn or clothesline

- Paper clips or clothes pins

- Introductory Essay

- Document Study: Ruling on Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

- Document Study: Responses to Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

- Large post-its (a different color for each group, if possible)

Notes to Teacher

The document study "Responses to Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education" includes letters that Judge Polier received after her Skipwith decision. Some of these letters were positive and complimentary, others were not. In an effort to represent both sides, we have included a letter from a school teacher in Indianapolis that is quite negative in the way that it refers to African American students. Please be sure to review this letter before teaching the lesson and contextualize it for your students.

De facto segregation in the North: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy, Civil Rights, Unit 2, Lesson 2

Civil Rights and the Courts

In the first half of the 20th century, civil rights were pursued primarily through the court system, as activists, organizations like the NAACP, and lawyers worked to overturn laws that permitted segregation and exclusion based on race. One of the greatest victories was the 1954 Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which overturned the precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that had legalized the doctrine of "separate but equal." "Separate but equal" provided the legal justification for segregation of facilities and services, including the school system. In practice, segregation of the school system in most communities was anything but equal, with the majority of resources going to white schools, which left African American students with access only to an inferior educational system. Moreover, segregation was psychologically harmful to students, cultivating a sense of inferiority in African American children and hampering their educational development.

In Brown v. Board, the Supreme Court unanimously declared segregated schools "inherently unequal" and unconstitutional, but did not order a clear timetable for the implementation of integration. Because some prominent southern politicians did not accept the Brown decision and blocked desegregation, the implementation of Brown led to some of the most vicious and protracted fights in the Civil Rights Movement. Little Rock, Arkansas was the site of the most famous resistance to desegregation, when Governor Orval Faubus called in the Arkansas National Guard to block nine black students from entering Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Unable to enter the school, the Little Rock Nine (as they were called) were harassed by a mob and threatened with lynching. The crisis attracted the attention of the nation, as well as of President Eisenhower, who met with the Governor and warned him not to interfere with the implementation of the Brown ruling. Ultimately, Eisenhower ordered the Army to Little Rock and federalized the Arkansas National Guard to remove them from Governor Faubus's control. By the end of September, the Little Rock Nine were able to enter the school with Army escort, though they suffered verbal and physical abuse from their fellow classmates throughout the tense school year. The following year (1958-59), all of Little Rock's high schools were shut to prevent further desegregation. (Many white students attended private schools that year, whereas most African American students, who did not have that option, lost a year of schooling.)

Segregation in the North

Though segregation was not the law in the northern states, neither were most school systems well integrated. Because school assignment was usually linked to neighborhood, the existence of residential segregation led to de facto segregation of the school system, (meaning they were segregated in reality, but not by law or de jure). Because school budgets were often linked to property taxes, poor neighborhoods tended to have poorer schools with inferior facilities. And the schools with a large non-white population tended to be staffed by inexperienced teachers who did not have seniority to choose a school district with more money and better resources. De facto segregation remained (and, in some places, remains) a common issue in the North, even many years after de jure segregation was outlawed in the South. Since there were no laws involved, de facto segregation was harder to combat, and in some ways more insidious, than de jure segregation.

De facto segregation of schools in the North could be a complicated issue for Jews. Though the majority of northern Jews supported civil rights, they also placed a great deal of emphasis on education and wanted their children to attend the best schools. Therefore, while they believed in integration in theory, Jews sometimes were unwilling to sacrifice their own children's education to that ideal. In addition, many of the white teachers and administrators in urban school systems like New York's were Jewish, so conflicts between the school faculty/administration and students/parents – as in the case of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school crisis in 1968 (see Unit 3 lesson 2) – often pitted Jews against African Americans.

Of course, this was not always the case, as illustrated by Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education – a court case that was decided by a prominent Jewish judge in favor of the black plaintiffs, holding the Board of Education responsible for de facto segregation of the schools.

Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

In 1958 the Skipwith family, which lived in New York City, boycotted their local public school because they felt their daughter was getting an inferior education. This school, like their neighborhood, was mostly black, and the teachers who worked at the school mostly were relatively inexperienced young, white teachers. Since the Skipwiths were not allowed to enroll their daughter in a school in a different neighborhood, the Skipwiths chose not to send their daughter to school at all. As a result, the New York City Board of Education charged the family with neglect. (Other black families in their neighborhood joined them in their boycott.)

The case, Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education, dealt with de facto segregation of the schools and the related issue of residential segregation. The case came before Judge Justine Wise Polier on the Family Court. Her handling of this case helped bring attention to the issue of de facto segregation. Her decision, presented on December 15, 1958, indicated that while the Board of Education was not responsible for de facto segregation, it was at fault for not providing qualified teachers to schools with fewer white students. (The School Board's policy up to this point was to allow teachers to choose their schools and few qualified, experienced teachers chose to work at non-white majority public schools.) Judge Polier went on to say that until the Board of Education rectified the situation, parents could not be punished for boycotting the schools. Each child had the right to a quality education.

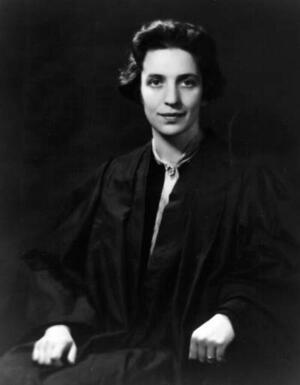

Justine Wise Polier (1903-1987)

Justine Wise Polier was born in 1903 to Rabbi Stephen Wise and Louise Waterman Wise. Her father, a founder of the American Jewish Congress, was a leading advocate of an Israeli state, one of the earliest supporters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and a pro-labor activist. Her mother was a painter, an ardent Zionist, and founder of a Jewish foster care and adoption agency.

As she came of age, Polier grew into the social activism modeled by her parents. While in college, she lived in a settlement house and taught English to immigrants. In her last year in college, she did research on women's workplace injuries and the inadequacy of their workmen's compensation. After college, Polier wanted to experience first-hand the lives of women laborers. Using her mother's maiden name (because her father's pro-labor stance was well known) she got a job in a textile factory, but anti-union spies discovered her identity and she was quickly blacklisted from the factory.

Polier then enrolled in Yale Law School. When a strike broke out at her former workplace, she commuted from Yale to participate in it, giving fiery speeches against the mill's "feudal tyranny" and terrible conditions and helping workers win the right to unionize.

After she graduated from law school, Polier worked for the Workman's Compensation Division in New York, helping to eliminate system-wide corruption and draft new laws. In 1935, she became the first woman judge in New York State, when was appointed to the Domestic Relations Court, where she spent the next thirty-eight years. Polier's most famous and influential decision was the 1958 Skipwith case.

Polier regularly used her position to fight for the poor and disempowered. She tried to implement juvenile justice law as treatment, not punishment, making her court the center of a community network that encompassed psychiatric services, economic aid, teachers, placement agencies, and families. She also fought religious and racial discrimination. At the time, New York relied for social services on private religious agencies, which often denied treatment and foster care to non-white children. No private services at all existed for black Protestant boys. Polier was so appalled that in 1936 she brought twenty cases to the mayor, who sent her to the Episcopalian Mission Society, which agreed to open the Wiltwyck School for boys.

Despite the changes brought by the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, Polier spent her final years as a judge still battling institutional racism. When Polier's attempts to find foster care for Shirley Wilder, an African American girl, were rejected by every agency, she helped initiate a class action suit. Wilder v. Sugarman, begun in 1974, charged public and private foster care agencies with unconstitutionally discriminating on the basis of religion and race. The controversial case spanned more than two decades.

Polier also served as vice-president of the American Jewish Congress and president of its women's division. Together with her husband Shad Polier, she spoke out about the importance of the Jewish community's commitment to civil rights.

Much of Polier's motivation came from her Jewish heritage. For her, to be a Jew meant an unwavering commitment to uphold the rights of all people and a moral obligation to speak out against injustice. She was deeply moved by the Jewish commitment to justice (often defined as a "prophetic tradition" because the biblical prophets were known for condemning rote religious behavior and corruption and for challenging their communities to live justly) and she spoke of this "vital heritage" as the most important guiding force in her life. Polier criticized American Jews for losing themselves in materialism and abandoning their responsibility to justice for "all human beings."

Introduction: Civil Rights Court Cases

- Break your class into small groups (or pairs) and give each group a Court Timeline Card. If you want to get students moving, you could copy the cards onto different colored paper, place them around the room, and ask students to pick them up and then get in line chronologically based on the year of their court case.

- Have each group/pair discuss the case on their Court Timeline Card and consider why their case is important in civil rights history. In deciding why their case is important your students may want to think about the following questions: Did it set a precedent that had an impact on African Americans? Did it change or reverse a precedent that had an impact on African Americans? What effect does this case still have on our lives today, if any?

- Have the groups put their Court Timeline Cards (back) in order, either by lining them up chronologically again, or by clipping the cards with paper clips or clothes pins to a piece of yarn or a clothesline strung in the front of the room. Once the cards are in order, have each group share with the class the following information about their court case: the decision, why it is important, and any Jewish role.

- After your students have returned to their seats, explain that in addition to moments of personal resistance, the earliest work to gain civil rights for African Americans was through the courts.

- Discuss the following questions with your class:

- Why do you think so many of these cases dealt with education? Why is equality of education so important?

- Segregation in public schools and universities in the South was instituted by law. Think about how you have segregation without laws. What are some examples?

- Write the words "de facto segregation" and "de jure segregation" on the board or on chart paper. Define both terms for your class. Have students give some possible examples and list them under the appropriate term.

Text Study: Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

- Explain to your students that as a class we will be examining another very significant civil rights case. As you read the documents and discuss them, think about how this case is similar to and/or different from the cases that are already on our timeline.

- Using the introductory essay, briefly explain the story of the Skipwith case to your students and provide some background on Judge Justine Wise Polier.

- Hand out copies of the document study "Ruling on Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education" to your students. Have a couple of students take turns reading out loud the excerpts from Justine Wise Polier's Skipwith ruling. You may want to stop the student occasionally to clarify terms and make sure your students understand the arguments being made.

- After reading the document, use some of the discussion questions found at the end of the document study "Ruling on Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education" to analyze the ruling with your students. (Be sure to print out an extra copy for yourself, so you can read the questions aloud.)

- When you're ready to move on, tell your students:

After her ruling on the Skipwith case, Justice Polier received many letters about the case from people she knew as well as from strangers. Newspaper columnists also wrote about it. To better understand this case and its impact, we're going to examine some of those letters and articles. - Have your students return to the same groups as at the beginning of class. Provide each group with a copy of the document study "Ruling on Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education," and ask them to review the documents and discuss the questions that follow each document.

- When the groups have finished their discussions, place the Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education timeline card on the timeline. Provide a pad of post-its to each group and have them write their responses to the following questions on separate post-its:

- What do you think is the importance of this case (use similar criteria as in the introduction)?

- What do you think was the Jewish influence on this case, if any?

- Each group should place their post-its on the Skipwith Timeline card as they finish writing them.

- After each group has placed its post-its, you can review them and group similar ideas together. Then share the main points written on the post-its with your class.

Conclusion: De Facto Segregation and You

- To wrap up this lesson, discuss the following questions with your class:

- How do these civil rights cases impact us today?

- Many would argue that de facto segregation in education still exists, even though there are no laws restricting African Americans from living in certain places, as there were at the time of the Skipwith case. What do you think de facto segregation looks like today?

- What are the demographics of your schools – Who is the majority? Who is the minority? (Encourage students to think about factors other than race as well.) How does this impact the school? If the school is not a public school, to what degree do parents choose the school for their children because of who the majority/minority population is?

Ruling on Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

Skipwith v. New York Board of Education Official Ruling excerpt

Excerpts from the official ruling:

Domestic Relations Court of the City of New York, Children’s court Division, New York County. In The Matter of Charlene SKIPWITH, Sheldon Rector, children twelve years of age.

December 15, 1958

JUSTINE WISE POLIER, Justice

…These parents assert, in justification of their refusal to send their children to these schools, that both schools offer educationally inferior opportunities as compared to the opportunities offered in schools of this city whose pupil population in largely white. This inferiority of educational opportunities, they assert, results from two conditions which they allege exist in these schools and for the existence of which conditions they claim the Board of Education is responsible. One of the alleged conditions is de facto racial segregation in these two schools all of whose pupils are either Negro or Puerto Rican. The other alleged concern is the discriminatory teacher staffing of these two schools with personnel having inferior qualifications to those possessed by teachers in junior high schools in New York City, whose pupil population is largely white.

As a consequence of the situation alleged to exist in these two schools, it is claimed that the children attending them are denied equal educational opportunities in violation of ‘equal protection of the laws’ guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States…

As was said in the Report of the Commission on Integration, submitted June 13, 1958:

‘Whether school segregation is the effect of law and custom as it is in the South, or has roots in residential segregation, as in New York City, its defects are inherent and incurable. In education there can be no such thing as ‘separate but equal.’ Educationally, as well as morally and socially, the only remedy for the segregated school is desegregation’...

Where, as here, power and responsibility for teacher assignment rests in the Board of Education, teachers who exercise that power are, in the…words of Mr. Justice Cardozo, ‘not acting in matters of merely private concern like the directors of agents of business corporations. They are acting in matter of public interest, matters immediately connected with the capacity of government to exercise its function.’…

The Board of Education can no more plead not guilty than could the Police Commissioner if he allowed patrolmen to choose not to accept dangerous or unpleasant assignments. No one would suppose that a new Police Commissioner would have performed his duty if he sought to remedy the situation by assigning police rookies to those tasks. Yet, in effect, that is all the Board of Education has done so far, in limiting the exercise of its power of assignment to the assignment of newly licensed teachers to the ‘X’ schools.*…

The courts of this State will not excuse failure of performance of a constitutional duty because the City of New York might be unwilling to pay the bill for the costs of what needs to be done…Nor will they relieve the Board of Education of its duties because of ‘hardship upon the existing teaching force’…

These parents have the constitutionally guaranteed right to elect no education for their children rather than to subject them to discriminatorily inferior education. I am wholly satisfied from their testimony and demeanor that this is not a case where parents have chosen to make such a choice without regard to the welfare of their children...In my judgment, the course upon which they embarked, and which brought them before this Court, was undertaken for the sake of their children and for the tens of thousands of other children like them who have been unfairly deprived of equal education.

The petitions are dismissed.

*From the ruling: “The term ‘X’ school is used to describe a school with a Negro and Puerto Rican population of 85% or more.”

Excerpts from the official ruling: Domestic Relations Court of the City of New York, Children’s court Division, New York County. In The Matter of Charlene SKIPWITH, Sheldon Rector, children twelve years of age. 15 December 1958.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote this document? When? What kind of document is it? For what audience(s) was it intended?

- In the Skipwith case the parents assert that their children's schools offer "inferior educational opportunities." Review the two reasons they give. What do you think of these reasons?

- According to Justice Polier (and Justice Cardozo) what is the difference between how teachers act and how directors of business act? Why is this significant in this case?

- Justice Polier makes a comparison between teachers and patrolmen. Do you agree or disagree with her reasoning? Why?

- The Skipwith case was brought before the court as a child welfare case because the parents were not sending their children to school. According to Justice Polier, these children were not being endangered by their parents' action. What is her argument supporting their actions? Do you agree or disagree with her argument? Why?

- What, if any, connections do you see between the schooling circumstances described in this case and circumstances within your own community?

- Who do you think should be held accountable for students' education in a community? (Refer back to the document for examples and think about your own community: students, parents, teachers, principals, Board of Education, local government, state government, federal government, officials in charge of housing and district lines, courts, community activists, etc.)

Responses to Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

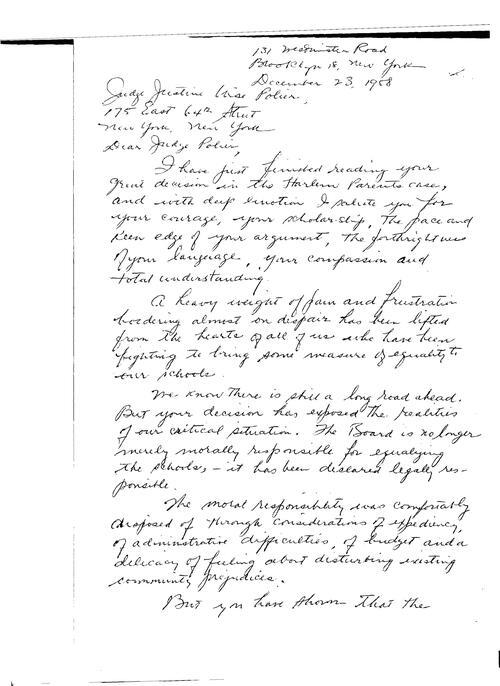

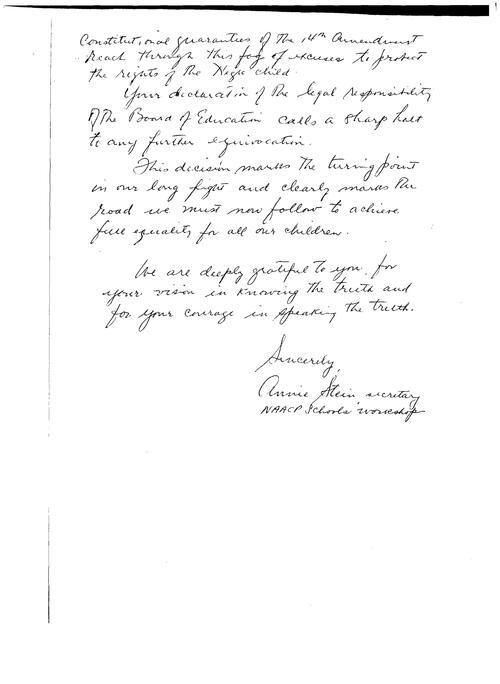

Letter to Justine Wise Polier from Annie Stein, December 23, 1958

Letter To Justine Wise Polier From Annie Stein, December 23, 1958, page 1

Letter To Justine Wise Polier From Annie Stein, December 23, 1958, page 1.

Courtesy of Eleanor Stein.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote this letter? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- Based on her letter, what is Annie Stein's point of view on the Skipwith decision?

- Stein talks about the difference between moral responsibility and legal responsibility in her letter. How are these responsibilities different? Which was the Board of Education missing in her mind? How did this allow them to get around making change? Do you think moral responsibility or legal responsibility is more powerful? Why?

- What did you learn about Annie Stein's background from the document? How, if at all, do you think this background might have informed her point of view? What else do you wish you knew about her?

"Wasting Time"

Another Angle column

Wasting Time

By James L. Hicks

…Last September several courageous Harlem mothers became fed up with paying teachers to warp the brains of their children, and flatly refused to send them to two of these inferior schools…

Once in the courts the mothers and their lawyers conclusively proved what we have been saying, that what they have been saying – that the Board of Education through its school administration, does discriminate against Negro and Puerto Rican children by refusing to give them an adequate supply of good permanent teachers, denying them the facilities afforded white students in so-called white schools and by conducting the Harlem schools in such a manner that the Negro and Puerto Rican child receives not only an inferior education but an inferiority complex as well…

In many respects in this case the New York Board of Education presents a much more bigoted attitude than many of the bigoted white boards of education in the South.

For in the South today even the bigots have accepted the fact that “separate but equal facilities” is a myth (and therefore unconstitutional) and today they are simply waging an all-out fight against integration.

But while Southern bigots have given up on separate but equal long ago, the New York Board is just getting around to losing a fight on the already outlawed doctrine. And despite its loss, it is at this late date considering appealing that loss to a higher court.

The Board thus finds itself belatedly trying to do what the bigots of the South have already found it impossible to do – to find a legal way to commit an illegal act with taxpayers’ money. …

James Hicks, "Wasting Time," Amsterdam News, (New York City, NY.) 3 January 1959.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote this article? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- Based on what you've read, what is his point of view on the Skipwith decision? What matters to him about this case?

- Based on what you know from his article, why does Hicks think that the situation is worse in the North than in the South? Do you agree or disagree with Hicks? Why?

- What do you think the experience of segregation meant to the people who lived in the North and the South? How do you think the lives of African Americans were different?

- What did you learn about James L. Hicks' background from the document and/or from additional reading? How, if at all do you think this background might have informed his point of view? What else do you wish you knew about him?

Letter from Mrs. L.O.K to Justine Wise Polier

Apr. 10, 1959

Judge Justine Wise Polier

Children's Court Division

Domestic Relations Court

New York City.

Dear Judge Polier:

In your article in the U.S. News of Jan. 9, 1959, you state that the best teachers in New York City are being allowed to choose their schools, and that the Negro and Puerto Rican schools are being assigned the weakest teachers.

As a former teacher in the Indianapolis Public schools, as the manager for ten years of 11 units of Negro property and as the wife of an architect who built Negro housing in Indiana, I should like to answer your complaint.

A huge percentage of the Negro pupils now in Northern schools, have come from the South, where segregation has existed for generations. Finding themselves in an integrated society, these formerly stable children, become arrogant and abusive; in other words, they go "haywire". Unfortunately, welfare workers, police and school principals have not cracked down sufficiently on these delinquents. (Could such laxness be due to fear of political retaliation?)

I know definitely of cases where Negro children have kicked, cursed and even threatened women teachers with physical assault; but it does these teachers no good to protest to their principals, for in many cases the principals merely say, "Settle these matters yourself." These teachers feel that they cannot do a good job of teaching under such circumstances; and I, as a former teacher, admire them for refusing to accept positions in Negro neighborhoods. If the Negro parents want better teachers for his neighborhood school, let him discipline his children, but the average Negro parent is apt to cry "Discrimination!" if his children are disciplined. And, I might add, runs to the NAACP with his story.

A stiff backed attitude by society in general would help immensely; for, after all, the whites have some rights, which are now ignored by welfare, church and judiciary groups.

I am particularly bitter today, because I have recently heard from two schools of Negro boys pushing white girls up against walls and fences and passing their hands over their bodies. What is the matter with the old fashioned whipping post?

In Cleveland, O., where I lived for nine years, there was no trouble with Chinese children; is there any reason why the Negro race cannot control its offspring?

As a result of my numerous contacts with Negroes, and as a result of Negro studies while living in four large cities, I am for Segregation with a capital S.

Yours. truly

[Signature]

(Mrs. L.O.) H.V.K.

[name & address redacted]

Indianapolis

Ind.

(Mrs. L.O.) H.V.K to Justice Justine Wise Polier, 10 April 1959, Polier, Justine Wise, 1903-1987. Papers, 1892-1990, Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliff College.

Letter from Justine Wise Polier to Mrs. LOK

May 11, 1959

Mrs. L.O.K

[name and address redacted]

Indianapolis, Ind.

Dear Mrs. K:

I received your letter concerning the report on a decision that I rendered.

My experience throughout over 23 years on the Bench has convinced me that as one comes to know people one cannot put any group in a separate category; that every religious, racial and national group has human beings of every variety among it. The task of America, which is a difficult one, is to evoke the best in each individual so that he or she can become educated in accordance with his ability and make the fullest use of his or her potential.

Certainly the American and religious tradition that all human beings are the children of God and brothers places a heavy obligation on those of us who believe in that ideal to work towards the abolition of the discrimination in our actions and the prejudice in our hearts which is so destructive to not only those who are subjected to it but to those who practice it.

With every good wish,

Sincerely,

Justine Wise Polier

JWP:mo

Justice Justine Wise Polier to (Mrs. L.O.) H.V.K, 10 April 1959, Polier, Justine Wise, 1903-1987. Papers, 1892-1990, Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliff College.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote these letters? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- What are Mrs. L.O.K.'s arguments against integration of schools? What solutions does she suggest?

- What did you learn about Mrs. K.'s background from letter? How do you think her background informed her point of view? What else do you wish you knew about her?

- What is the difference between how Judge Polier views "people" and how Mrs.K. views "people?" How is this difference significant to this case and civil rights in general?

- What did you learn about Judge Polier's background from her letter? How do you think her background informed her point of view in writing this letter? Do you think it also informed the way she ruled in the Skipwith case? If yes, do you think a judge should only take the law and facts in a case into account when making a ruling or should they take other things into account as well?

Dred Scott v. Sanford

Date: 1857

Description:

Dred Scott was a slave from Missouri, who traveled with his master to the free states of Illinois and Wisconsin. When Scott returned to Missouri he sued for his freedom, claiming that since he had lived in free states he was now free.

Decision:

Ten years after Scott first brought his suit, the Supreme Court ruled against him. The majority opinion stated that blacks were not included as "citizens" in the US Constitution and therefore could not claim any of the rights or privileges listed in that document.

Plessy v. Ferguson

Date: 1896

Description:

Homer Plessy, a 30-year-old black man who lived in Louisiana, was arrested for sitting in the White Only car of the East Louisiana Railroad. He went to court, saying that the law that allowed for separate cars for black people and white people violated the fourteenth amendment (which provides for equal protection under the law). The case worked its way from the local level all the way up to the Supreme Court.

Decision:

Each court, including the Supreme Court, found Plessy guilty of not leaving the white car. The majority opinion stated that "A statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races -- a distinction which is founded in the color of the two races, and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color -- has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races..." This came to be known as the "separate but equal" doctrine.

Morgan v. Virginia

Date: 1946

Description:

In July 1944, Irene Morgan was arrested when she refused to yield her seat to a white passenger on a bus from Virginia to Maryland. Morgan was tried and convicted of violating a state segregation ordinance. Her conviction was upheld by the state appellate court. The following year, lawyers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took on Morgan's case. The NAACP argued that statutes requiring segregation on interstate carriers placed an undue burden on interstate commerce and thus violated the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Decision:

In a 7 to 1 ruling on June 3, 1946, the Supreme Court reversed the Virginia appellate court decision, striking down the Virginia law and, by extension, the laws in other states mandating Jim Crow practices on interstate transport.

In April 1947, an interracial group of sixteen people under the auspices of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) engaged in a "Journey of Reconciliation" to call attention to the Court's decision and to force adherence to it. The journey was a precursor to the Freedom Rides of 1961.

Méndez v. Westminster

Date: 1946

Description:

Gonzalo Méndez and his family moved to Westminster in Orange County, CA in 1943. Méndez, a native of Westminster, attempted to enroll his children in the same elementary school that he had attended as a child only to learn that new Jim Crow laws had since been enacted. As Mexican immigration to the United States grew, the Westminster school system ruled that students of Mexican descent must attend a segregated school and were no longer permitted to enroll at Westminster Elementary School. Refusing to abide by the Jim Crow laws, Méndez, along with several other Mexican-American parents and with the help of the League of Latin American Citizens, sued four school districts in Orange County, CA for enforcing segregation. Méndez’s lawyers argued that segregation was illegal under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Decision:

Senior District Judge Paul McCormick ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, rejecting the “separate but equal” doctrine made precedent in the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Orange County schools appealed the decision, but the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously upheld the ruling. In 1947, Earl Warren, then the governor of California, signed the Anderson Bill, thus revoking the state’s segregation statutes. Warren was later appointed as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, where he presided over the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Sweatt v. Painter

Date: 1950

Description:

Herman Marion Sweatt applied to the University of Texas Law School in 1946. Since the University of Texas Law School was only for white students and Herman Sweatt was black, the University denied his application. Sweatt then sued the university, which attempted to set up an equal, but separate program for him and other black law students. The case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court

Decision:

In 1950, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of Herman Marion Sweatt, claiming that the "law school for Negroes" which the University of Texas meant to open would not and could not be equal to the school for white students. There would be inequalities of faculty, library facilities, and course offerings. In addition, just the fact that the black students would be separate from the majority of other law students would do them harm.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents

Date: 1950

Description:

George W. McLaurin applied to the University of Oklahoma's graduate program in education. Since state law mandated segregation in education, the University denied his application. McLaurin brought a suit against the university in Federal court in Oklahoma. The court indicated that the University did have to accept George McLaurin as a student. The University was not entirely comfortable with this decision and tried to segregate McLaurin on campus by making him sit separately in the library, in classes, and in the cafeteria. Because of this treatment, McLaurin appealed his case which then went to the Supreme Court.

Decision:

The Supreme Court found in favor of McLaurin. The majority opinion stated that the treatment that McLaurin received at the University violated the 14th amendment and that since McLaurin could not easily mix with other students the school was preventing him from learning his chosen profession.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

Date: 1954

Description:

In 1951, thirteen black parents living in Topeka, KS, and working with the NAACP tried to enroll their children in the school closest to where they lived, which was a school only for white students. Not surprisingly, they were told that they could not enroll their children in this school. The parents then brought a class action suit against the Topeka Board of Education to try and get it to end its policy of segregated education. The court case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, which issued a decision in 1954.

Decision:

The Supreme Court found in favor of the parents. They stated that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. It is not possible to have "separate but equal" facilities.

Jewish Participation:

In 1950, the American Jewish Committee hired a black psychologist, Kenneth Clark, to study the impact of school segregation on black children. He found that segregated education had a large impact on black children's self-esteem. Clark's research and findings became a major part of the brief prepared by the NAACP in this case.

Boynton v. Virginia

Date: 1960

Description:

In 1958, Bruce Boynton was on his way home to Montgomery, Alabama, when he took a seat and ordered a snack in the white only section of a restaurant at a Trailway bus station during a brief stop in his trip. Since the restaurant was segregated and Bruce Boynton was black, he was asked to move to the colored section of the restaurant. Boynton refused to leave and maintained that since he was an interstate bus passenger he was protected by Federal anti-Segregation laws. The staff at the restaurant called the police and Bruce Boynton was arrested and fined $10.

Decision:

The case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court which ruled, in 1960, that racial segregation in public transportation violated the interstate commerce act.

Loving v. Virginia

Date: 1967

Description:

In 1958, Mildred Jeter, an African American woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, got married in Washington, D.C. They were both residents of Virginia, but had gone to the District of Columbia to get married in order to avoid their state's ban on interracial marriages. After the wedding, they returned to Virginia. They were later arrested in their home and charged with breaking the law. They pled guilty and were sentenced to one year in jail. The American Civil Liberties Union picked up their case and brought it as far as the Supreme Court.

Decision:

The Supreme Court, in an unusual 9-0 decision, overturned the law banning interracial marriages in Virginia, finding it unconstitutional based on the 14th Amendment.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education

Date: 1971

Description:

North Carolina was a comparatively moderate southern state when it came to civil rights and integration, yet by the mid-1960s it had still not successfully integrated all of its schools. One area where schools were still segregated based on neighborhood was Charlotte, NC. In 1965, the NAACP brought a suit against the Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education, calling on them to do more to integrate the schools. A plan to bus students from different neighborhoods in order to better integrate the schools was developed. However, the school board maintained that it was not constitutionally required to make this change.

Decision:

The Supreme Court unanimously supported Swann and the plan to bus students. It stated that when previous plans had failed to resolve the issues of segregation, the local courts did indeed have the power to impose a plan on the school board.

Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

Date: 1958

Description:

De facto

Comes from Latin and means "from the fact." In law cases it is used to refer to situations that exist but that are not mandated by law. It is the opposite of de jure. De facto segregation is segregation that exists, but not based on laws.

De jure

Comes from Latin and means "concerning the law." In law cases it is used to refer to what the law says. De jure segregation is segregation based on actual laws.