Q & A with Photographer Dana Stirling

JWA talks with photographer Dana Stirling about her new book, Why Am I Sad, her passion for film photography, and the importance of speaking openly about our mental health struggles.

JWA: Tell us more about your new photography book, Why Am I Sad. What was your inspiration for the project, and how did you select the images for it?

Dana Stirling: In many ways, this book and project have been evolving for years. My work has always been a continuum—open-ended and non-linear. It doesn’t conform to a traditional narrative with a clear beginning or end. Family dynamics, identity, and my challenges with belonging have always been central themes in my photography, so this project felt like a natural progression.

I’ve been fortunate to achieve meaningful milestones in my career, but like many artists, I’ve also faced struggles—both in my professional life and with my mental health. Growing up with a mother who suffers from clinical depression profoundly shaped who I am. Photography became my way of coping and processing these emotions from an early age. However, navigating this connection hasn’t always been easy. There were times when I felt too sad to photograph, which in turn made me anxious about not creating art. This anxiety deepened my depression, creating a difficult cycle to break.

In 2019, my husband, Yoav, and I took our first trip to the West Coast. The landscape was breathtakingly beautiful and unlike anything I had experienced in New York. One moment in particular stood out: a scene with vibrant purple flowers surrounding a red driveway hazard reflector. I photographed it because I found it both ironically beautiful and deeply moving. That moment reignited my passion for photography, reminding me why I fell in love with it in the first place. It sparked a renewed sense of purpose and inspired me to reflect on my complex relationship with photography and the emotions tied to it.

This led me to an open-ended question: Why am I sad? It’s not an easy question, and perhaps it’s impossible to fully answer, but it became the core of what I was feeling. The more I allowed myself to speak openly about my struggles and let my photography guide me through these emotions, the clearer the project became. That moment marked the true beginning of this journey.

Curating the images for the book was a challenging process. Some photographs didn’t make it into the final edit—not because they lacked value but because they didn’t align with the specific narrative I wanted to convey. Choosing what to include ultimately came down to the flow of the story, the constraints of the book format, and the message I wanted the viewer to experience. However, I don’t see these “left behind” images as discarded. They remain part of this ongoing exploration and may find their place in the future as the project continues to grow and evolve.

JWA: What draws you to photography— particularly film photography—as a means of expression?

DS: Growing up, I was mesmerized by my grandfather’s talent for drawing. He would sit and effortlessly sketch black-and-white pencil drawings of animals that were both intricate and beautiful. I admired him deeply for that creativity, and I often wished I could possess that same artistic gift. But drawing wasn’t my talent. I spent years trying to find my creative voice, growing up in the shadow of his artistry. I tried to fit myself into boxes I thought made sense for me—like writing—but it never felt right. I wasn’t good at it, and more importantly, it wasn’t my passion.

In hindsight, I think I always had an innate connection to photography, even if I didn’t realize it at the time. Both my father and grandfather shared photography as a hobby back in their days in London. My grandfather documented life with his camera, and my father enjoyed the darkroom. Perhaps this shared interest was quietly passed down to me, waiting to surface.

I first discovered photography as a fun little pastime, taking photos of friends and experimenting with still life around my home. It felt comforting and personal. As I delved deeper, learning the technical aspects of photography and upgrading to a better camera, I realized how much I enjoyed the process. Eventually, I decided to take it more seriously and pursued an undergraduate degree in photography to develop my skills professionally.

During the first year of my BA program, we were only allowed to use black-and-white film. We had to learn to shoot, develop, and print our images—a process that was both challenging and transformative. This experience was foundational, teaching me the importance of composition, as well as the intricate relationship between light and shadow. It shaped how I see the world through a camera.

The real turning point for me came when we were finally allowed to work with color. I fell in love with it—especially with analog film. It felt like coming home, as though the medium was an extension of who I am. Film photography holds a magic that I haven’t found anywhere else. There’s something profound about looking through a viewfinder, seeing the world framed through that glass. It’s now an integral part of my process, and I can’t imagine creating images any other way.

JWA: What do you hope readers and viewers will understand about you and mental health in general when they encounter your work?

DS: Most importantly, I want people to see that it’s okay to talk about these things. Growing up, shame was deeply embedded in my family dynamic. You never discussed your struggles, and you certainly didn’t share them with anyone outside the home. Keeping everything private, almost like a family secret, became the root of many personal challenges I faced and, I believe, shaped the way my family functioned as a whole. For me, learning to step away from that ingrained sense of shame and guilt has been a liberating and eye-opening experience. Through my work, I hope to create a space where people feel comfortable engaging with heavy and uncomfortable topics in a way that still feels positive and meaningful.

This book and my work are not meant to be a definitive representation of what depression is or how it looks. Mental health is an incredibly personal experience, and it manifests differently for everyone. What I’m offering is a glimpse into how it feels through my eyes—through the lens of my own life, shaped by a family heritage marked by depression. My work reflects the interplay between sadness and moments of humor and beauty, as well as the weight of isolation, loneliness, and burden.

I hope viewers see themselves in these images and objects—recognizing their own stories and emotions alongside mine. Ultimately, I want this project to inspire people to share more openly about their struggles, to feel less alone, and to find beauty in the complexities of their experiences.

JWA: You write in the book about your mother’s clinical depression and how it shaped your childhood. As a first-generation child of immigrants, do you find that other cultures have a different approach to understanding mental health than they do in the United States?

DS: In many ways, I’ve felt like an immigrant my entire life. My parents moved from London to Jerusalem in 1988, and I was born there in 1989. Even though Jerusalem was my birthplace, I always felt like an outsider. Our home was distinctly British—my parents spoke English and broken Hebrew, and we held onto traditions and habits that set us apart from the Israeli culture around us. I felt different because our food, language, and way of life didn’t match those of my peers. Then, years later, when I moved to the US, I became an immigrant once again. This sense of navigating between cultures has been a constant in my life.

Living within these cultural intersections made me realize that, no matter where you are, fear of judgment is universal. People hesitate to share their struggles, worried about what others might think. Would they be judged? Would opportunities be taken away? Would they be seen as less capable or less qualified? While I can’t speak for everyone or any culture as a whole, my experience has shown me that these fears often keep people from having honest conversations about mental health.

In the post-pandemic world, I’ve seen a noticeable shift in how mental health is discussed. There’s a growing awareness that mental health challenges are widespread and that people can still lead successful, fulfilling lives while managing these struggles. The more these conversations happen, the more we can chip away at the stigma and shame surrounding mental health. I wish these open discussions and resources had been available to me as a teenager when I desperately needed them. By fostering dialogue and understanding now, I hope to contribute to a world where people feel supported and empowered to seek the help they need.

JWA: What's a common misconception about depression and mental health that you’d like to see change?

One common misconception about depression and mental health is that it looks the same for everyone or that it’s always visibly apparent. People often assume that if someone is depressed, they’ll appear sad, withdrawn, or struggling outwardly. But the reality is far more complex. Depression can manifest in many ways—it’s not always about crying or staying in bed. It can also look like someone showing up to work, socializing, and even achieving success while carrying an immense internal weight.

I think this misunderstanding often leads to judgment or dismissal of people’s struggles. It creates a culture where individuals feel pressured to prove their pain or justify their need for support, which only deepens the sense of isolation.Through my work, I aim to highlight that mental health experiences are deeply personal and multifaceted. Depression can coexist with humor, beauty, and moments of joy. It’s not a one-size-fits-all experience. I hope we can move toward a more compassionate understanding—one where we don’t expect people to fit a stereotype of mental illness, but instead offer space for them to share their unique journey.

This idea is at the heart of the book cover, designed by Elisha Zepeda. The cover features something seemingly simple—a happy face sticker—but with a powerful twist: it’s torn and flipped upside down, transforming it into a sad face. To me, this symbolizes the duality of emotions—that behind every happy face, there’s often a trace of sadness. They coexist, intertwined, and both are equally valid and important.

We live in a world where we often feel compelled to put on a brave face, masking the weight of our internal struggles. But this doesn’t mean those struggles disappear—they stay with us, shaping who we are. This cover encapsulates that truth, encouraging us to embrace the full spectrum of our emotions. It’s a reminder that it’s okay to carry both joy and sadness with us, as long as we allow ourselves to be open and honest about what we’re feeling.

JWA: Do you have a favorite image in the book or an image that was particularly meaningful for you to capture?

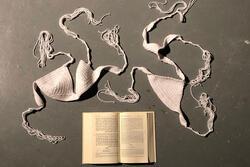

DS: In addition to the photo mentioned earlier, there’s another image I took —a toy deer lying upside down on a shelf. Even though this photo was created years before this project took shape, it remains one of my favorite and most significant images. On the day I captured it, I was feeling deeply lost and overwhelmed, unable to process my emotions. At that moment, I turned to photography, instinctively picking up my camera to photograph something—anything—that caught my eye.

I came across this small, toy deer and decided to photograph it. I placed it upside down because that pose perfectly reflected how I felt inside: disoriented, vulnerable, and broken. To me, this image is a self-portrait. It was a moment of clarity where I truly understood the power of photography, especially still life photography, as a way to channel and express emotions that words could not convey.

Still life photography often goes unappreciated because it speaks in symbols and metaphors, requiring viewers to pause, look deeply, and decode the layers of meaning embedded in everyday objects. In today’s fast-paced world, this act of slowing down and engaging thoughtfully can feel like a challenge, but for me, it’s the very reason I’m drawn to still life. It holds a unique power—enigmatic on one hand, yet profoundly universal on the other.

This image might not be a traditional self-portrait, but it represents me as an artist and as a person. It’s a distilled version of my inner world, and it reflects the essence of how I use photography to document my emotions and navigate my experiences.

JWA: In 2014, you co-founded the photography magazine Float with the aim of creating a community of both established and emerging photographers. What has that community meant to you?

DS: Float was created by my husband, Yoav Friedlander, and me in 2014. Our goal was to establish a space for photography that was open-minded, inclusive, and supportive—a platform that could genuinely nurture fellow artists and peers. Over the years, we’ve been honored to collaborate with so many talented artists, sharing their work and fostering a community of like-minded individuals united by a shared passion for art and photography.

Our mission has always been to create a platform that embraces diverse perspectives, voices, and visions, offering something meaningful for everyone. Whether through our online presence, exhibitions, or printed publications, we strive to build connections and make art accessible and engaging for as many people as possible.

For me, this community is more than just a network of artists—it’s been a true source of support and friendship. I firmly believe in the power of artists helping artists. When we uplift and celebrate one another, we all grow stronger. I don’t believe in keeping resources or knowledge to myself; the more we share, the more we all benefit. By fostering collaboration and celebrating each other’s successes, we create a healthy and vibrant dynamic that allows art to thrive.