Karaite Women

The Karaites, a group that follows the Bible more closely and rejects the divinity of the Oral Law that is central to Rabbinite Judaism, observe their own distinct laws, including those for women and family life. Family law and personal status of women are important aspects of both the daily life and the halakhah of Karaite communities. They also have a significant impact on the relationships between Karaite and Rabbanite Jews. Karaite legal sources often deal with rules pertaining to betrothal, marriage, divorce, ritual purity, and incest.

Family law and personal status of women are important aspects of both the daily life and the The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah of Karaite communities. Karaite legal sources often deal with rules pertaining to betrothal, marriage, divorce, ritual purity, and incest. Crucial to the identity and the continuity of Karaite community, these issues had considerable impact on the relationships between Karaites and mainstream Rabbanite Jews. In consequence, they were subjected to sustained polemical discussions and modifications during the emergence and the “golden age” of the movement, between the eighth and the twelfth centuries, in Babylonia, Egypt, and Palestine.

The Karaites

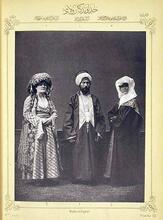

Often defined as a separatist “sect,” Karaism in fact originated as a distinctive religious and intellectual movement inside Judaism itself. It was initiated in eighth-century Babylonia, and medieval Jewish and Arab sources link its origins with a member of the family of Jewish exilarchs, Anan ben David. Some scholars have argued that there exists a direct link between medieval Karaites and some Second Temple Jewish sects, but at present there is not sufficient evidence to ascertain continuity or a direct influence reaching from antiquity. While the movement was first established in Iraq and Persia, some followers of Karaism migrated towards the Mediterranean by the end of the ninth century. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, well-established Karaite communities existed in Egypt, North Africa, and Spain, and also in Palestine where, from the tenth century, Jerusalem became the most influential intellectual center and the seat of the Karaite academy of learning. Simultaneously, Karaite communities spread into Byzantium, reaching Crimea, and later, in the fourteenth century, Lithuania. Today, the most important Karaite community is in Israel, its religious center located in Ramle. This community is composed mainly of Egyptian and Iraqi Karaites. European Karaites still dwell in Lithuania, as well as in Russia, Poland, Western Europe, and the United States.

From the outset, the most essential aspect of Karaite doctrines has concerned the sources and authority of law. According to the principle most clearly formulated by Jacob al-Qirqisani (ninth century) under the partial influence of the Muslim Mu‘tazila school, the binding authority of Karaite laws and customs derives from one of three legal principles: the Bible (the Pentateuch, Prophets, and Hagiographa) (al-nass), the analogy (al-qiyas), and the consensus of the nation as a whole (al-ijma‘) (Kitab al-Anwar II. 18:1). The latter is often identified with “tradition” (naqal) and “inheritance” (wiratha). While the Bible is considered to be of divine origin, the analogy and the consensus (tradition) are of human making. The laws based on any of these principles are equally binding, but their theoretical status is different, in that the laws derived by analogy or consensus cannot overrule or stand in contradiction with the biblical text. This theoretical approach to the sources of halakhah implies that the Karaites rejected the divine origin attributed to the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud and the authority of its sages. This does not mean that the Karaites do not observe non-Biblical laws and customs; in fact many binding Karaite rules, and notably those concerning women (e.g. the marriage contract, Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah) are not mentioned in the Bible, and are clearly identical to the Rabbanite practices recorded in Talmudic and Geonic literature. At the same time, the Karaites rejected the post-Biblical teachings that seem to be in contradiction to the word of the Bible. The Bible itself was interpreted literally, with particular attention to the nuances of the Hebrew language. This interpretation could be highly personal, as every adult (male) Karaite has a duty to study the Bible individually, without relying on any “canonical” corpus of commentaries or authorities. Such freedom was already posited in an apocryphal dictum attributed to Anan ben David: “Search well in the Bible, and do not rely on my opinion.” It requires thorough knowledge of the language of the Bible and its grammar, and also leads inevitably to a multiplicity of interpretations.

The Sources

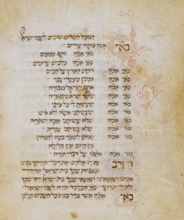

The importance of laws and customs regarding women and their personal status is reflected in Karaite scholarly works and commentaries from the very beginning of the movement. Those aspects in which the Karaites differed from the Rabbanites (such as the permissibility of marriage and the definition of incest) were dealt with in great detail in special sections in early Karaite codes of law, such as the Sefer A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.Mitzvot of Anan ben David (Baghdad, eighth century), the Kitab al-Anwar wal-Maraqib of Jacob al-Qirqisani (Iraq, 937), and the Sefer Mitzvot of Levi ben Yefet (Palestine, early eleventh century). These issues were also mentioned in various works and commentaries by such authors as Benjamin al-Nahawendi (Babylonia, ninth century), Daniel al-Qumisi (Babylonia-Palestine, tenth century), Yefet ben Ali (Babylonia-Palestine, tenth century), and Yusuf al-Basir (Babylonia-Palestine, early eleventh century), and generated a number of dedicated monographs, such as the book on prohibited categories of kinship by Solomon ben David, the Karaite Nasi (Palestine, tenth century), and the Sefer Arayot or Sefer ha-Yashar by Jehoshua ben Jehuda. These two monographs are polemical in nature, and their authors criticized in particular the laws of incest, namely the theory of “chain reaction” or “compounding” (rikkuv), as upheld by earlier Karaite authorities. The topic of incest also received a great deal of attention among later Karaites, for example in Byzantine legal compendia such as Eshkol ha-Kofer by Jehuda Hadassi (twelfth century), Gan Eden by Aharon ben Eliya (fourteenth century), and Aderet Eliyahu by Eliyahu Bashyaci (sixteenth century).

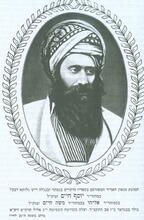

The laws of betrothal and marriage have received less attention, except for the aforementioned later Byzantine authors who also devoted specific sections of their legal compendia to these topics. Nevertheless, most of the early essential rules can be gleaned and reconstructed from various discussions in major codes of law, such as those of Anan ben David (in his discussions on Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).levirate marriage (yibbum)), Benjamin al-Nahawendi, Jacob al-Qirqisani, and Levi ben Yefet. These sources can be complemented by actual legal contracts pertaining to marriage, which have been preserved in the Cairo Place for storing books or ritual objects which have become unusable.Genizah (tenth–twelfth centuries) and in the Abraham Firkovitch (1786–1874) collections in Saint Petersburg (mainly from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries).

Permissibility of Marriage

In order to contract marriage, the parties must be “marriageable,” that is: the partners must be Jewish, the woman must be unmarried, and the parties should not fall into any of the kinship categories prohibited by Karaite law.

1. The parties’ religious affiliation

Marriages with non-Jewish partners are not acceptable for Karaites. Marriages with Rabbanite partners were perfectly legal and commonly practised before the thirteenth century. Medieval Karaism was and saw itself as an integral part of Judaism, and such marriages did not entail any form of “conversion” of any of the parties. Seven marriage contracts involving Karaite and Rabbanite individuals have so far been discovered in the Cairo Genizah. These marriage contracts stipulated the mutual tolerance of those practices in which the Karaites and the Rabbanites differed. These specific stipulations concerned differences in dietary law, such as the Rabbanite husband’s promise not to bring to their house parts of animals authorized by the Rabbanites but forbidden by the Karaite halakhah (the fat tail, the kidneys, the lobe of the liver, the meat of a pregnant animal). Other stipulations concerned the Karaite restrictions on lighting the Sabbath candles and the promise of Rabbanite husbands not to make love to their Karaite wives during Sabbath and festivals—practices strictly forbidden by Karaite law. Due to the calendrical differences, Karaite and Rabbanite festivals did not coincide, and the marriage contracts always included a clause which guaranteed that both parties would be allowed to observe their festivals on their respective dates.

Marriages between Karaite and Rabbanite partners came to a halt when Moses Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon (Rambam), b. Spain, 1138Rambam, 1138–1204) argued that while the Karaite marriage itself was binding, their bill of divorce was invalid (probably because of its formulation in Hebrew). Since the children issued from the second union of a Karaite divorcée would be illegitimate (mamzerim), and since it was not always possible to ascertain that a divorce had not occured in previous generations in a Karaite family, Maimonides decided to consider all Karaites as potential mamzerim, and therefore prohibited for marriage. This prohibition was not universally accepted and remains in debate today in Israel.

2. Polygamy

While the marriage of a woman to more than one man at a time is forbidden, a Karaite man could in principle have more than one wife provided he could fulfill all his duties towards both women. However, the right of the husband to take a second wife could be restricted through the inclusion of a special anti-polygamy clause in the betrothal or marriage contract.

3. Prohibited Categories of Kinship

The prohibited categories of kinship are derived by Karaite authors from all three principles of the Karaite halakhah: the biblical text, the analogy, and the consensus of the community. The most important categories of prohibited relatives are mentioned in Lev. 18:6–18 and 20:14. They are: parents, stepmother, mother-in-law, sister and half-sister, stepsister, grand-daughter, father’s and mother’s sister, wife of father’s brother, daughter-in-law, brother’s wife, stepdaughter and step-grand-daughter, and wife’s sister, even after the first wife’s death or divorce. These categories, some based on consanguinity and others on ties by marriage, are all considered as blood relations and called she’ar basar (“flesh”). Unlike the Rabbanites, who put limits on the use of analogy in the matters of incest, prior to the eleventh century the Karaites used analogy, and analogy upon analogy to the fourth degree in order to derive from these basic categories further forbidden degrees of kinship. These analogical derivations were based on three principles:

- The prohibitions set in the Bible work “upwards” and “downwards” along generations. For example, the prohibition of granddaughters in Lev. 18:10 concerns all the generations of their descendants, and implies the prohibition of grandparents, great-grandparents, etc.

- The prohibitions apply from one gender to the other. When Lev. 18:9 states, for example, that a sister is forbidden to her brother, this implies that also the brother is forbidden to his sister.

- The prohibitions apply across lineages. The biblical “Hence a man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, so that they become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24) was understood literally, and implied that all the members of the wife’s family become automatically the kinsmen of the groom and his family. This widening of the prohibited degrees of kinship by marriage (rikkuv) was practiced from Anan’s times until the second half of the eleventh century.

Other prohibited degrees of kinship derived from other biblical verses, include Benjamin al-Nahawendi’s prohibition (based on Song of Songs 8:1) of the marriage between milk sisters and brothers, i.e. otherwise unrelated individuals who were nursed by the same woman.

This excessive use of analogical derivations from the Bible led in practice to the multiplication of the prohibited categories of kinship. These prohibited categories included three cases in which the Karaite law was in opposition to Rabbanite rules:

- The marriage of a man to his wife’s sister even after the dissolution of the marriage (derived in a different way by Karaite authors from Lev. 18:14 or Lev. 18:18).

- Marriage with one’s niece, based on principles of gender equivalence and continuity along generations. Lev. 18:12-13 contains a prohibition for a man to marry his maternal or paternal aunt, and since it applies to both sexes, it also prohibits a woman’s marrying her paternal or maternal uncle, and effectively the uncle to marry his niece.

- The marriage of two brothers with two sisters, derived either from the literal interpretation of Gen. 2:24 (above), or from Lev. 18:16: “Do not uncover the nakedness of your brother’s wife; it is the nakedness of your brother.” According to the principle of gender equivalence, whoever of his own kin is forbidden to the husband, the corresponding kin of his wife is also forbidden to him. Thus, one’s wife becomes her husband’s brother’s sister, and so does her sister.

This extensive use of analogy widened the circle of consanguinity to such an extent that marriageable partners became increasingly scarce. The rules of rikkuv were finally abolished in the eleventh century through the arguments of Yusuf al-Basir and especially his Jerusalemite disciple, Jehoshua ben Jehuda. Since then, the prohibited kinship degrees (she’ar, “flesh”) have been only those explicitly mentioned in Lev. 18:6–18, their blood relatives (she’ar ha-she’ar “flesh of the flesh”), and those who are derived from them by analogy to the first degree only.

Levirate Marriage

The biblical rules of levirate (the duty of a man to marry the widow of his deceased brother or kinsman) and its possible exemption by Mandated ceremony (Deut. 25:9halizah (Deut. 25:5–10) were compulsory when a childless woman was widowed or when her fiancé died after the betrothal and before the actual marriage. However, the strict incest rules discussed above actually forbade the real brother of the deceased to marry his widow, and the duty of levirate marriage was incumbent upon “permissible” family members (e.g. cousins).

Betrothal

Before the actual marriage, the marriageable partners became engaged to each other in a betrothal ceremony (erusin). The act of betrothal constituted a binding financial engagement, which involved the payment by the fiancé of a part of the marriage payment and his promise to pay the second part of the marriage payment at a later stage. The payment was made to an agent (pakid), who had been previously appointed by the fiancée in court, in the presence of two witnesses. The betrothal, the money transfer, and further guarantees for the period between the betrothal and the marriage itself are recorded in a written document (sefer erus), established before the court and witnesses. If the actual marriage did not take place at the date agreed on, the fiancé was bound to provide for his fiancée’s needs. In case of breach of promise, the fiancé had to release his fiancée with a letter of divorce and also pay a penalty equal to one half of the advance marriage payment.

Marriage

Three elements are essential for contracting a Karaite marriage: marriage payments (mohar), writ (ketubbah) and sexual intercourse (bi’ah). The mohar given by the Karaite groom consists of three distinct payments, all three necessary for the validity of the marriage: the basic marriage payment and the additional marriage payment, which is in turn divided into advance (mukdam) and delayed (me’uhar) portions. The basic marriage payment was given by the groom in its totality on the day of the marriage. Its amount, derived from Ex. 22:16 and Deut. 22:16, was fixed at an early stage of Karaite halakhah to fifty silver coins if the bride was a virgin, and twenty-five silver coins if she was a widow or a divorcée. The amount of the additional marriage payment was not fixed, but negotiated according to the economic capacities of the parties. It was paid in two portions: advance, which was paid in totality at the betrothal, or partly at the betrothal and partly at the marriage itself (together with the basic marriage payment), and delayed, which remained as a debt upon the husband, stipulated in the ketubbah. It was not paid to the woman during the marriage but in the event of its dissolution, and remained a guarantee of the woman’s financial security.

The wife brought into the marriage the dowry or trousseau given to her by her father or his heirs. The dowry legally belonged to the wife, but remained under her husband’s jurisdiction for the duration of the marriage. The husband had full rights to use and enjoy these items of property, but he was also legally liable for them, and had to return them intact (or pay their exact monetary value) upon the eventual dissolution of the marriage.

Inheritance

In Karaite law, the husband is not the automatic heir of his wife. If she dies childless before her husband, her entire dowry must be returned to her father or his heirs, while the husband retains only the delayed portion of the additional marriage payment. If the couple has children, the dowry remains with the husband until his death, when the children inherit it. Among the Karaites, unlike the Rabbanites, daughters have equal rights of inheritance with sons. However, after his wife’s death the widower could remarry and have children by a second wife, who could potentially share the inheritance left by the first wife. To prevent this, a Karaite woman was entitled to issue a special document to ensure that her dowry would be inherited only by her own children. The wife could also enforce the inheritance of her estate by her children from a previous marriage by inserting a special stipulation into her marriage contract.

Divorce

The legal procedure of Karaite divorce, its possible grounds, the instrumental role of the letter of divorce and its consequences are all derived from Deut. 24:1–4: “If a man takes a woman and marries her, and if later she finds no favour in his eyes because he found in her a shameful thing, he will then write for her a letter of divorcement, give it into her hands and send her away from his house. If this woman, after departing his house, marries another man, and if this latter husband hates her too and writes her a letter of divorce, gives it into her hands and sends her away from his house, or if this latter husband dies, her former husband who divorced her cannot take her again to be his wife”. However, the unilateral aspect of the divorce described in the Bible—initiated and carried out exclusively by the husband—was not maintained by the Karaite sages, who strengthened the rights of the woman: in order to divorce his wife, the husband must have solid and sufficient reason to do so, not trivial incidents or disagreements, and the woman’s readiness to discontinue the marriage must be taken into consideration. Some early scholars accepted the woman’s right to initiate the divorce by demanding the courts to coerce her husband to write her a letter of divorce, especially if the husband did not fulfil his three obligations: food, clothes and sexual intercourse, as derived from Ex. 21:11—obligations which he undertook to fulfil in the marriage contract.

From the early eleventh century, the Karaite halakhah introduced a real reinforcement of women’s rights in matters of divorce: divorce by juridical decree. First mentioned by Levi ben Yefet ha-Levi in his Book of Precepts, this practice has been maintained by later Karaites until today and constitutes a distinctive feature of Karaite divorce law. It amounts to the right of the Karaite court to issue a letter of divorce if the husband himself refuses to do so.

Ritual Purity

The rules regulating the behaviour of and towards women during the period of menstruation or after childbirth have been dealt with in great detail by Karaites authorities since Anan ben David. The Karaites obeyed these rules with particular care. The blood of menstruation (Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah), vaginal discharge (zavah), or childbirth (ledah) render the woman unclean. For a prescribed period of time, she may not have sexual intercourse with her husband, nor may she enter places of worship. According to many Karaite authors, she must also refrain from cooking and other domestic chores (although Anan ben David allows her to kindle the fire), and should be almost completely separated from her normal surroundings. The impurity caused by the blood of a menstruating woman can be transferred to any person or objects (bedding, clothing, or seat) in contact with her. After a certain length of time, and according to her condition, she must purify herself by immersion in running water (though not in a ritual bath, as Karaites do not practice the institution of Ritual bathmikveh). Purification is also required for people or objects that she rendered unclean. Although different Karaite authors held various and sometimes divergent opinions about certain aspects of the laws of purity, the basic rules are based on biblical injunction as expressed in Lev. 15:19–29 and Lev. 20:18. A menstruating woman is considered unclean and can transmit the impurity for seven days after the beginning of her menses. Since the ramifications of contact with menstrual blood are important, Karaite authors often deal with the ways of determining the beginning of menstruation. When a woman feels the first blood of menstruation, there is no doubt when the period of seven ritually impure days has begun. But since women often see blood only later, without knowing the precise moment when their menses have begun, Karaite authors advise that a woman should check regularly for blood when the usual time of her menstruation approaches, and in case she does not feel the exact moment, her period of impurity counts from the last time she checked. If she did not check, it counts from the day her menstruation was normally due to begin. The period of seven days of ritual impurity is counted from the moment she sees her blood. If she sees no further blood on the eighth day, she is ritually pure, and permitted to her husband after washing (unlike the period of at least twelve days prescribed by the Rabbanites). If she notices any blood after the seventh day, the woman is considered to have a discharge (zavah). Now, in order to be permitted to her husband, she needs to count seven “clean days” once blood flow has ceased.

The rules concerning a woman after childbirth are based on Lev. 12:1–8. According to the Bible, a woman is unclean for seven days after the birth of a boy and for two weeks after the birth of a girl. In addition, she may not participate in religious life nor may she enter the sanctuary for a further thirty-three days after the birth of a boy and sixty-six after the birth of a girl. According to most Karaite authors, a woman is unclean (and may not engage in sexual intercourse with her husband) just as she is during menstruation, for the full forty days after the birth of a boy and eighty days after the birth of a girl.

In conclusion, while Karaite laws concerning women and their status are mostly similar to those practiced by mainstream Rabbanite Jews, there are several differences which result either from the Karaite reinterpretation of relevant biblical passages or from the influence of Muslim laws and customs. Many of these distinctive features, such as the wife’s right to initiate divorce or the equal rights of daughters and sons to their father’s estate, indicate the high legal and social position of Karaite women in medieval Jewish communities.

Ben-Sasson, Menachem. “Firkovitch’s Second Collection: Remarks on Historical and Halakhic Material” (Hebrew). Jewish Studies 31 (1991): 47–67.

Frank, Daniel. “The Study of Medieval Karaism, 1959–1989.” Bulletin of Judaeo-Greek Studies 6 (1990): 15–23.

Ibid. “The Study of Medieval Karaism, 1989–1999.” In Hebrew Scholarship and the Medieval World, edited by Nicholas De Lange, 3–22. Cambridge: 2001.

Karaites: General History

Ankori, Zvi. Karaites in Byzantium: The Formative Years, 970–1100. New York and Jerusalem: 1959.

Ben-Sasson, Hayyim Hillel. “The Karaite Community of Jerusalem in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries” (Hebrew). Shalem 2 (1976): 1–18.

Ben-Shammai, Haggai. “A Fragment of Daniel al-Qumisi’s Commentary on Daniel as a source for the History of Palestine” (Hebrew). Shalem 3 (1981): 295–307.

Ibid. “The Karaites” (Hebrew). In The History of Jerusalem: The Early Islamic Period (638–1099), edited by Joshua Prawer, 163–178. Jerusalem: 1987.

Brinner, William M. “Karaites of Christendom, Karaites of Islam.” In Essays in Honor of Bernard Lewis, edited by Clifford E. Bosworth et al., 55–73. Princeton: 1989.

El-Kodsi, Mourad. The Karaite Communities in Poland, Lithuania, Russia and Crimea. Lyons, NY: 1993.

Erder, Yoram. “The Karaites’ Sadducee Dilemma.” IOS 14 (1994): 195–226.

Gil, Moshe. The Tustaris: Family and Sect (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1981.

Khan, Geoffrey. The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought. Leiden, Boston, Köln: 2000.

Lasker, Daniel. “Islamic Influences on Karaite Origins.” In Studies in Islamic and Judaic Traditions II, edited by William M. Brinner and S. D. Ricks, 23–47. Atlanta: 1989.

Ibid. “Karaism in Twelfth-Century Spain.” Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy 1 (1992): 179–195.

Ibid. Karaism and Jewish Studies (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 2000.

Mann, Jacob, Texts and Studies in Jewish History and Literature, 2 vols, Cincinnati-Philadelphia: 1931–1935.

Miller, Phillip E. Karaite Separatism in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Joseph Solomon Lutski’s Epistle of Israel’s Deliverance. Cincinnati: 1993.

Nemoy, Leon, Karaite Anthology. New Haven and London: 1952.

Pinsker, Simhah. Likkutei Kadmoniot. Vienna: 1860.

Polliack, Meira R. The Karaite Tradition of Arabic Bible Translation: A Linguistic and Exegetical Study of Karaite Translations of the Pentateuch from the 10th and 11th Centuries. Leiden: 1997.

Schur, Nathan. History of the Karaites. Frankfurt a/Main: 1992.

Szyszman, Simon. Les Karaïtes d’Europe. Uppsala: 1989.

Trevisan-Semi, Emanuela. Les Caraïtes: un autre judaïsme. Paris: 1992.

Karaite Halakhah Concerning Women

Aaron ben Eliya. Gan Eden. Eupatoria: 1864 (edition).

Corinaldi, Michael. “The Problem of Divorce by Judicial Decree in Karaite Halakhah.” Dinei Israel 9 (1979–1980): 101–144.

Ibid. The Personal Status of the Karaites (Hebrew), Jerusalem: 1984.

Ibid. “Karaite Halakhah.” In An Introduction to the History and Sources of Jewish Law, edited by Neil S. Hecht et al., 251–269. Oxford: 1996.

Eliyahu ben Moses Bashyaci. Aderet Eliyahu. Odessa: 1870 (edition princeps Constantinople: 1530).

Firkovitch, Abraham, ed. Aaron ben Joseph’s Mivhar Yesharim, containing Mas’at Binjamin, Benjamin al-Nahawendi’s Book of Legal Decisions, Eupatoria: 1834.

Eisenstein, Judah David. “The Karaite Law of Incest” (Hebrew). Ozar Israel VIII, London: 1935: 143–145.

Friedman, Mordechai A. Jewish Marriage in Palestine: A Cairo Genizah Study. 2 vols, Tel Aviv and New York: 1980–1981.

Ibid. Jewish Polygyny in the Middle Ages: New Documents from the Cairo Genizah (Hebrew). Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: 1986.

Ginzberg, Louis. Ginzei Schechter: Genizah Studies in Memory of Doctor Solomon Schechter, Part II: Geonic and Early Karaite Halakhah (Hebrew). New York: 1929.

Harkavy, Albert E., ed. Sefer Mitzvot le-Anan. Studien und Mittheilungen aus der K. Oeffentlichen Bibliothek zu St. Petersburg, vol. VIII, St. Petersburg: 1903.

Jacob al-Qirqisani. Kitab al-Anwar wal-Maraqib. Code of Karaite Law by Ya‘aqub al-Qirqisani, edited by Leon Nemoy. 5 vols, New York: 1939–1945.

Jehoshua ben Jehuda, ed. Sources for Women and Incest Rules among the Karaites. Part I: Sefer ha-Yashar of Jehoshua ben Jehuda (Hebrew), edited by Isaac Dov Markon. St. Petersburg: 1908.

Jehuda Hadassi. Eshkol ha-Kofer, edition Eupatoria: 1836.

Levi ben Yefet, Book of Precepts, MS Warner 22 and MS I Firkovitch Heb. A. 613.

Nemoy, Leon. “Two controversial points in the Karaite law of incest.” HUCA 49 (1978): 247–265.

Olszowy-Schlanger, Judith. “La lettre de divorce caraïte et sa place dans les relations entre Caraïtes et Rabbanites au moyen 'ge.” REJ 155 (1996): 261–285.

Ibid. Karaite Marriage Documents from the Cairo Genizah. Legal Tradition and Community Life in Mediaeval Egypt and Palestine, Leiden, New York, Köln: 1998.

Revel, Bernard. The Karaite Halakhah and its Relation to Sadducean, Samaritan and Philonian Halakhah. Philadelphia: 1913.

Schechter, Solomon. “Genizah specimens (TS 24.1).” JQR 13 (1900–1901): 218–221.

Ibid. Documents of Jewish Sectaries, vol. II: Fragments of the Book of Commandments by Anan, Cambridge: 1910.

Solomon ben David ben Boaz ha-Nasi, I Firk. MS Heb.-Ar. 3921.