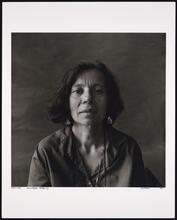

Kadya Molodowsky

Kadya Molodowsky was a major figure in the Yiddish literary scene in Warsaw (from the 1920s through 1935) and in New York (from 1935 until her death in 1975). A teacher in the Yiddish schools in Warsaw as a young woman, she was best known for her children's poems. In the United States, she wrote for the Yiddish press and founded and edited a journal, Sviva (Surroundings), which she published for three decades. Living in Israel (1948-52), she founded and edited a journal, Heym. She published six major books of poems (1927-1965), novels, short stories, plays, and essays. Recurrent themes in her work include the lives of Jewish women and girls, Jewish tradition in the face of modernity, Israel, and the Holocaust.

And why should this blood without blemish

Be my conscience, like a silken thread

Bound upon my brain,

And my life, a page plucked from a holy book,

The first line torn?

These lines, from Kadya Molodowsky’s 1927 sequence “Froyen-Lider” [Women-poems], pose a crucial question: How can a Yiddish woman writer reconcile her art with Judaism’s definition of a woman’s role? Molodowsky’s answer to that question in her poems, children’s poems, novels, short stories, essays, plays, autobiography, and journalism, published between 1927 and 1974, evolved into even broader questions about the very survival of Jews in the modern world.

Family and Education

Kadya Molodowsky was born in the (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetl Bereza Kartuska, White Russia, located within the czarist Russian province of Grodino (now the Belarus Oblast’ of Brest), on May 10, 1894. The second of four children, Kadya had an older sister, Lena, and two younger siblings, a sister, Dora (Dobe), and a brother, Leybl. Her father, Isaac, a learned Jew who taught Hebrew and Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Gemara [commentary on the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah] to young boys in heder [elementary Jewish school], was also an adherent of the Enlightenment and an admirer of Moses Montefiore and Theodor Herzl. Her mother, Itke (the daughter of Kadish Katz/Kaplan, for whom Kadya was named), ran a dry-goods shop and later opened a factory for making rye kvass.

Molodowsky was taught to read Yiddish by her paternal grandmother, Bobe Shifre. Her father instructed her in the study of the Hebrew Pentateuch and also hired various Russian tutors to teach her Russian language, geography, philosophy, and world history. Such an education, especially the instruction in Hebrew, was highly unusual for a girl in the shtetl, and according to her niece and nephew, Edith Schwartz and Ben Litman, Kadya was better educated than either of her sisters.

At seventeen, Molodowsky passed the high school graduation exams in Libave. She tutored students in Bereza until her eighteenth birthday, when she obtained her teaching certificate. From 1911 to 1913, she taught in Sherpetz and in Bialystok, where her mother’s sister lived and where she joined a Hebrew-language revivalist group. From 1913 to 1914, she studied under Yehiel Halperin in Warsaw to earn qualification for teaching Hebrew to children. At the start of World War I, Molodowsky worked in Warsaw at a day-home for displaced Jewish children, sponsored by her teacher Yehiel Halperin. Between 1914 and 1916, she worked at teaching and day-home jobs in such towns as Poltave and in such cities as Rommy and Saratov on the Volga. From the summer of 1916 until 1917, Molodowsky taught kindergarten and studied elementary education in Odessa, where Halperin had moved his Hebrew course to escape the war front.

Early Poetry and Teaching

In 1917, after the Bolshevik Revolution, Molodowsky attempted to return to her parents in Bereza but was halted in Kiev. There, she worked as a private tutor and in a home for Jewish children displaced by the pogroms in the Ukraine. In 1920, having survived the Kiev pogrom, she published her first poem in Eygns (Authenticity), a journal of avant-garde poetry founded by David Bergelson. In Kiev, she met Simkhe Lev, a young scholar and teacher originally from the shtetl of Lekhevitsh. They married in the winter of 1921. The couple settled in Warsaw until 1935, except for a period around 1923, when they worked at a children’s home sponsored by the Joint Distribution Committee in Brest-Litovsk.

In Warsaw, Molodowsky taught in two schools: by day in the elementary school of the Central Yiddish School Organization (known by its acronym, TSHISHO), and in the evenings at a Jewish community school. She was active in the Yiddish Writers Union at Tlomatske Street 13, where she met other writers from Warsaw, Vilna, and America.

In 1927, Molodowsky published her first book of poetry, Kheshvendike Nekht (Nights of Heshvan), under the imprint of a prestigious Vilna and Warsaw Yiddish publisher, B. Kletskin. The book’s narrator, a woman in her thirties, moves through the landscape of Jewish eastern Europe. Molodowsky contrasts the narrator’s modernity with the roles decreed by the Jewish tradition for women, according to law, custom, or history. Kheshvendike Nekht received approximately twenty reviews in the Yiddish press, nearly all laudatory.

Deeply aware of the poverty in which many of her students lived, Molodowsky wrote poems for and about them. Her second book, Geyen Shikhelekh Avek: Mayselekh (Little shoes go away: Tales), published in Warsaw in 1930, was awarded a prize by the Warsaw Jewish Community and the Yiddish Pen Club.

Molodowsky’s third book of poems, Dzshike Gas (Dzshike Street), published in 1933 by the press of the leading Warsaw literary journal, Literarishe Bleter, was reviewed negatively on political grounds for being too “aesthetic.” Her fourth book, Freydke (1935), features a sixteen-part narrative poem about a heroic Jewish working-class woman.

Immigration to the United States and Mature Writing

In 1929, Molodowsky joined Simkhe Lev, her husband, in Paris while he studied at the Sorbonne; in 1931, the couple returned to Warsaw in an economically troubled and anti-Semitic Poland. In 1935, Molodowsky was invited to the United States to give a reading tour and to launch a children’s magazine in Yiddish. She stayed, settling in New York City, and was able to bring her husband there in July 1938. Her fifth book, In Land fun Mayn Gebeyn (In the country of my bones, 1937), contains fragmented poems that represent an internalization of her exile.

Molodowsky’s literary endeavors then branched out in several directions. In 1938, she published a new edition of her children’s poems, Afn Barg (On the mountain), and a children’s play, Ale Fenster tsu der Zun (All Windows Face the Sun) appeared in Warsaw in 1938. In 1942, she published Fun Lublin Biz Nyu-York: Togbukh fun Rivke Zilberg (From Lublin to New York: Diary of Rivke Zilberg), a novel about a young immigrant woman.

Fearful for her brother, his wife Lola, and their baby daughter, as well as other family in Nazi-occupied Poland in 1944, Molodowsky put aside her editorship of the literary journal Svive (Surroundings), which she had cofounded in 1943 with another recent immigrant from Warsaw, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and published seven issues. In these years, she began to write the poems of Der Melekh Dovid Aleyn Iz Geblibn (Only King David remained, 1946), a book comprised of many khurbn-lider (poems of the Destruction) that draw upon traditional Jewish literary responses to catastrophe and are some of her best poems. After the war, Molodowsky, her father, and her sisters learned that Leybl died trying to escape from a communist concentration camp near Bialystok in 1942 or 1943, and that Lola and their daughter had been murdered by the Nazis.

In 1945, another edition of Molodowsky’s children’s poems, Yidishe Kinder (Jewish children), was published in New York. That same year, a book of her children’s poems in Hebrew translations by Lea Goldberg, Nathan Alterman, Fanya Bergshteyn, Avraham Levinson, and Yakov Faykhman appeared in Tel Aviv. She published a long poem, Donna Gracia Mendes; a second play, Nokhn Got fun Midbar (After the God of the desert, 1949), which was produced in Buenos Aires, Chicago and in Israel; and a chapbook of poems, In Yerushalayim Kumen Malokhim (In Jerusalem, angels come, 1952). According to biographer Zelda Kahan Newman, Molodowsky rewrote her novel Fun Lublin Biz Nyu-York: Togbukh fun Rivke Zilberg (From Lublin to New York: Diary of Rivke Zilberg) as a play, A Hoyz Oyf Grand Strit (A House on Grand Street), which, although never published, was produced at the President Theater on Broadway in October 1953. From 1954 to 1956, Molodowsky wrote a series of columns on great Jewish women for the Yiddish daily Forverts, using Rivke Zilberg, the name of the novel’s protagonist, as a pseudonym, or, as Anita Norich argues, an authorial persona. In addition, a book of essays, Af di Vegn fun Tsion (On the roads of Zion), and a collection of short stories, A Shtub mit Zibn Fentster (A house with seven windows), both appeared in New York in 1957. In 1962, Molodowsky edited an anthology, Lider fun Khurbm (Poems of the Holocaust. In 1960, she revived the literary journal Svive, which she published through 1974.

From 1948 through 1952, Molodowsky and Simkhe Lev lived in Tel Aviv. There, Molodowsky edited a Yiddish journal for pioneer women, Heym (Home), which portrayed life in Israel. She also began work on a novel, Baym Toyer: Roman fun dem Lebn in Yisroel (At the gate: Novel about life in Israel), which was not published until 1967. At the end of this period, she began to write her autobiography, Fun Mayn Elter-zeydns Yerushe (From my great-grandfather’s inheritance), which appeared serially in Svive between March 1965 and April 1974.

Published in Buenos Aires in 1965, Molodowsky’s last book of poems, Likht fun Dornboym (Lights of the thorn bush), includes dramatic monologues in the voices of legendary personae from Jewish and non-Jewish traditions and contemporary characters. The book concludes with a section of poems on Israel from the 1950s, which, like the ending of her autobiography, express Molodowsky’s Zionism.

In Tel Aviv, in 1971, Molodowsky received the Itzik Manger Prize, the most prestigious award in the world of Yiddish letters, for her achievement in poetry. After the death of her husband, Simkhe Lev, in 1974, she moved to a nursing home in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, near the family of her sister Dora Litman. There, Kadya Molodowsky died, on March 23, 1975.

The Poet and Her Poetry

Session on "Queer Dreams of Jewish Women's Poetry" for the Jewish Women's Archive's Global Day of Learning, in celebration of the launch of the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, June 28, 2021. Featuring Zohar Weiman-Kelman in conversation with Judith Rosenbaum.

For nearly 50 years, from 1927 through 1974, Kadya Molodowsky published prolifically and continuously in all genres—poetry, fiction, drama, essays, memoir, journalism. The poems she wrote for children throughout her life became classics in Yiddish schools in Poland and North America, and in Hebrew translation in Israel, where they are still read and sung by young children. She founded and edited two journals, in Tel Aviv and in New York, and saw her plays produced on stage. A woman of letters in every sense, Molodowsky influenced Yiddish literature in Poland, Israel, and the United States. She sustained a focus on girls and women as subjects, readers, and creators of literature and culture throughout her writings, from her early poem sequences, the tkhine-invoking “Froyen-Lider” [Women-poems] and the labor study of “Oreme Vayber” (Poor Women)”; through children’s poems, such as “Olke,” a girl who escapes poverty by reading; her political poems, “Dzshike Gas” (Dzshike Street), “Mayn papirene brik” (My Paper Bridge), and “Freydke”; and her late poems, such as “Dos Gezang fun Shabes” (The Sabbath Song), “Der Vint iz Alt Gevorn” (The Wind Has Grown Old), and “Oyf der Papirene Brik” (On the Paper Bridge). Only a few among her khurbnlider (poems of the Destruction), speak with a markedly female persona, such as “Mayne kinder” (My Children), yet Molodowsky’s great poems that lament the losses and rebuke God, most famously, “Eyl Khanun” (Merciful God), transform the male-intoned Jewish tradition with the authoritative voice of a woman.

Selected Works

In Yiddish:

A Shtub mit Zibn Fentster. New York: Farlag Matones, 1957.

Af di Vegn fun Tsion. New York: Pinchas Gingold Farlag of the National Committee of the Jewish Folk Schools, 1957.

Ale Fentster tsu der Zun: Shpil in Elef Bilder. Warsaw: Literarishe Bleter, 1938.

Baym Toyer, roman. New York: CYCO, 1967.

Der Melekh Dovid Aleyn Iz Geblibn. New York: Farlag Papirene Brik, 1946.

Dzshike Gas: Lider. 1933; 2nd ed. Warsaw: Literarishe Bleter, 1936.

Freydke: Lider, 1935; 2nd ed., Warsaw: Literarishe Bleter, 1936.

Fun Lublin biz Nyu-York: Togbukh fun Rivke Zilberg. New York: Farlag Papirene Brik, 1942.

In Land fun Mayn Gebeyn: Lider. Chicago: L. M. Stein,1937.

In Yerushalyim Kumen Malokhim: Lider. New York: Farlag Papirene Brik, 1952.

Kheshvendike Nekht: Lider. Vilna: B. Kletskin,1927.

Lider fun Khurbn: Antologye, ed. Tel Aviv: Farlag I. L. Peretz,1962.

Likht fun Dornboym: Lider un Poeme. Buenos Aires: Poaley Tsion Histadrut,1965.

Martsepanes: Mayselekh un Lider far Kinder. New York: Bildungs-Komitet fun Arbeter Ring un CYCO, 1970.

Mayn Elterzeydns Yerushe. Svive. March 1965–April 1974.

Mayselekh. Warsaw: Yidishe Shul Organizatsye in Poyln, 1930.

“Meydlekh, froyen, vayber, un...nevue.” Literarishe Bleter 4, no. 22 (June 3, 1927): 416.

Nokhn Got fun Midbar: Drame. New York: Farlag Papirene Brik, 1949.

Svive, ed, (1943–1944; 1955–1974).

Yidishe Kinder: Mayselekh. New York: Tsentral-Komitet fun di Yidishe Folks-shuln in di Fareynikte Shtatn un Kanade, 1945.

In Translation:

A Jewish Refugee in New York: Rivke Zilberg’s Journal: A Novel by Kadya Molodowsky. Translated by Anita Norich. Bloomington, Indiana: 2019.

Lelot Ḥeshvan: shirim (Heshvan nights: poems). Translation into Hebrew. Supplementary texts by Amir Shomroni. Edited by Abraham Nowersztern. Berak, Israel: Hakibbutz Hame’uhad and Beit Shalom ‘Alekhem, 2017.

Paper Bridges: Selected Poems of Kadya Molodowsky. Translated, edited, introduced by Kathryn Hellerstein. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999.

Pithu et Hasha’ar: Shirei Yeladim. Hebrew translations by Nathan Alterman, Lea Goldberg, Fanya Bergshteyn, Avraham Levinson (1979).

Gonshor, Anna Fishman. “Kadye Molodowsky in Literarishe bleter, 1925-1935: Annotated Bibliography.” M.A. thesis, McGill University, Montreal, 1997.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. A Question of Tradition: Women Poets in Yiddish, 1586-1987. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2014.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “Hebraisms as Metaphor in Kadya Molodowsky’s Froyen-Lider I.” In The Uses of Adversity: Failure and Accommodation in Reader Response, edited by Ellen Spolsky, 143-152. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1990.

Hellerstein, Kathryn.“In Exile in the Mother Tongue: Yiddish and the Woman Poet.” In Borders, Boundaries, and Frames: Essays in Cultural Criticism and Cultural Studies (Essays from the English Institute), edited by Mae G. Henderson. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “Kadya Molodowsky’s Froyen-Lider: A Reading.” AJS Review 13, nos. 1–2 (1988): 47–79.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “A Question of Tradition: Women Poets in Yiddish.” In Handbook of American-Jewish Literature: An Analytical Guide to Topics, Themes, and Sources, edited by Lewis Fried, 195-237. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “The Subordination of Prayer to Narrative in Modern Yiddish Poems.” In Parable and Story as Sources of Jewish and Christian Theology, edited by Clemens Thoma and Michael Wyschogrod, 205-236. Lucerne: Paulist Press, 1989.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “A Yiddish Poet’s Response to the Khurbm: Kadya Molodowsky in America.” Translated into Hebrew by Shalom Luria. Chulyot: Journal of Yiddish Research 3 (Spring 1996): 235–253.

Howe, Irving, Ruth R. Wisse, and Khone Shmeruk, eds. The Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse. New York: Viking, 1987.

Klepfisz, Irena. “Di Mames, dos Loshn/The Mothers, the Language: Feminism, Yidishkayt, and the Politics of Memory.” Bridges 4, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 1994): 12–47.

Newman, Zelda Kahan. Kadya Molodowsky: the Life of a Yiddish Woman Writer. Washington, DC: Academica Press, 2018.

Newman, Zelda Kahan. “The Correspondence Between Kadya Molodowsky and Rokhl Korn. Women in Judaism 8, no. 1(Spring 2011): 1-26.

Peczenik, F. “Encountering the Matriarchy: Kadye Molodowsky’s Women Songs.” Yiddish 7, nos. 2–3 (1988): 170–173.

Pratt, Norma Fain. “Culture and Radical Politics: Yiddish Women Writers in America, 1890–1940.” In Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing, edited by Judith R. Baskin, 111-135. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994.

Weiman-Kelman, Zohar. Queer Expectations: A Genealogy of Jewish Women's Poetry. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2018.

Zucker, Sheva. “Kadye Molodowsky’s ‘Froyen Lider.’” Yiddish 9, no. 2 (1994): 44–51.