Yiddish: Women's Poetry

Women, the original consumers of traditional Yiddish literature, were central to the development and evolution of literary Yiddish culture. Flourishing in the 1920s, Yiddish women’s poetry began as a bilingual shift from external languages into Yiddish, representing a return to the Jewish cultural fold from circles that had previously distanced themselves. Many women made their entry into Yiddish literature mainly through poetry’s close connection with what was presumed to be “women’s writing.” Yiddish women’s poetry pushed Yiddish literary creativity in all of its major centers, especially New York and Israel. Yiddish poetry was more daring than prose in its search for new forms; it thus afforded women writers broader opportunities to create works in tune with contemporary literary trends.

Women’s poetry in Yiddish first made its presence felt within the wider context of modern Yiddish culture at the end of the second decade of the twentieth century. In 1917–1918 the first poems of Celia Dropkin and Rashelle Veprinsky were published. The poems of Kadya Molodowsky appeared in 1920 in the literary anthology Eygns (volume 2), the most significant contribution to the new center of Yiddish literature that developed in Ukraine. In the same year, the poems of Anna Margolin began to appear in New York, while at the same time the first works of Miriam Ulinover and Rokhl Korn appeared in Eastern Europe. Thus, women’s poetry in Yiddish emerged concurrently in several centers of modern Yiddish culture, becoming one of the outstanding manifestations of its growth and diversity. The appearance of the comprehensive and visually splendid anthology, Yidishe dikhterins (Yiddish women writers, Chicago: 1928), edited by Ezra Korman, served as the most palpable sign of the emergence of women’s Yiddish poetry as a separate literary corpus and generated debate as to its nature and value.

Yiddish Women’s Poetry and Bilingualism

In comparing the early work of women writers in Yiddish with that of their male counterparts at the beginning of the twentieth century and after, one can discern a striking linguistic and cultural characteristic of the women’s writing: Celia Dropkin and Anna Margolin first tried their hand at writing in Russian (their works in this language were not published), while Rokhl Korn published her early writings in Polish, later switching to Yiddish. Malka Heifetz Tussman began writing prose in English almost immediately upon her arrival in the United States and moved to Yiddish on the recommendation of her literary mentor. In the 1920s the poet and writer Fradel Shtok published a work of prose in English, but it was totally ignored. In contrast to the male writers, there are no outstanding instances of women poets whose choice of language oscillated between Yiddish and Hebrew. (Molodowsky’s education apparently afforded her sufficient fluency in Hebrew, but she did not attempt to write in that language.)

These modest displays of bilingualism that mark the early writings of the Yiddish women poets are indicative of the unique cultural world of Jewish women in Eastern Europe, where Yiddish was already facing competition, whether explicit or implicit, from the local vernacular. This factor contributed to the positive reception of women’s poetry in Yiddish, since the critics felt that the very emergence of such a literary corpus was an additional indication of the Jewish renaissance and marked the return to the Jewish cultural fold of circles that had begun to distance themselves from it. For this reason, the initial response of the literary critics to women’s poetry in Yiddish was favorable, albeit based on clear assumptions regarding the desired nature of “women’s writing.”

Expansion from Eastern Europe to Israel and New York

Women’s poetry in the twentieth century was an integral part of Yiddish literary creativity in all of its major centers: Kyiv (Shifre Kholodenko); Warsaw (where Kadya Molodowsky and Rajzel Zychlinski, among others, produced their works); Lodz (Miriam Ulinover, Rikudah Potash); Lviv (Dvoyre Fogel); Montreal (Ida Maze, Rokhl Korn, Chava Rosenfarb); Los Angeles (where Malka Heifetz Tussman and Esther Shumiatcher resided for many years); and Buenos Aires (Sore Birnboym).

A number of women poets played a role in the gradual expansion of the literary center in Israel especially after the establishment of the state: Rikudah Potash, Malka Loker (both of whom immigrated to pre-state Palestine before 1948), Rivka Ben-Hayim Basman, Rokhl Fishman, Shifra Werber, and Hadassa Rubin. But throughout this period the largest center for women poets writing in Yiddish was unquestionably New York City, which left its mark on the literary careers of Fradel Shtok, Bertha Kling, Celia Dropkin, Anna Margolin, and Malka Lee. In addition, other poets who had produced much of their work in Eastern Europe also found their way to New York at various stages in their lives. These included Rosa Gutman-Jasny, Kadya Molodowsky, and Rajzel Zychlinski. The lives of several women writers were spent in a perpetual state of wandering: Rosa Gutman-Jasny, Esther Shumiatcher, and Dore Teitlboym. In only a very few instances is it possible to point to an explicit link between the poets’ place of residence and their writings; in the entire corpus of women’s poetry in Yiddish one can discern the traces of only two clearly defined geographical and cultural realms: the metropolis of New York on the one hand and the varied landscapes of Israel on the other.

Poetry as Women’s Entry into Yiddish Literature

The list of outstanding women poets in Yiddish indicates that, as with the Hebrew literature of the period, women made their entry into Yiddish literature mainly through poetry. Although women made a significant contribution to many genres in Yiddish literature, the close connection between “women’s writing” and “poetry” persisted throughout its history, despite the fact that women writers also spanned the genres in their diversity: Fradel Shtok, who published stories and poems in New York beginning in 1910, collected only her stories into a book, while her poems remained dispersed. The short stories of Celia Dropkin and Rokhl Korn, by contrast, constituted an integral and prominent part of their work, but their poetry nonetheless took pride of place in their body of work as a whole. This was also the case with Kadya Molodowsky, who, along with numerous volumes of poetry, also published a drama in book form (1949), a collection of short stories (1957), and two novels. In this respect, Chava Rosenfarb is the outstanding exception that proves the rule: she began her literary career after the Holocaust by writing poetry, but later devoted herself primarily to prose.

Several possible explanations can be offered for the fact that the majority of women writers in Yiddish chose poetry as their medium of expression: Women faced much greater difficulties than men if they wished to become professional writers, partly because the opportunities for earning a livelihood from Yiddish writing were closely associated with journalism, which was to all intents and purposes the province exclusively of men. But although one can only speculate as to the causes of Yiddish women writers’ distinct preference for poetry in the world of Yiddish culture, there is one striking key effect: in the interwar period, Yiddish poetry was more daring than prose in its search for new forms and its modernistic features; thus, the choice of poetry afforded the women writers broader opportunities to create works more in tune with contemporary literary trends. In terms of prosody, the women poets preferred free verse to the traditional poetic forms. Indeed, there is a noticeable tension in women’s Yiddish poetry between modernism and conventional literary trends—a tension that took on a unique quality in light of the connection between women and the world of Yiddish culture.

Women as Original Consumers of Yiddish Literature

Women were the natural consumers of traditional Yiddish literature; several of its sub-genres, first and foremost the tkhines, were identified almost exclusively with the world of women. This point was elucidated in Samuel Niger’s comprehensive and pioneering study of traditional Yiddish literature, Yiddish Literature and the Female Reader (1913), which offered a reasoned analysis of the special connection between women and Yiddish literature over the centuries. While Niger pointed to those genres in premodern Yiddish literature in which the woman’s voice could be heard either implicitly or explicitly (for example, in several types of folk songs), the very title of his study indicates that in traditional Yiddish literature women were primarily the target audience of literature written by men.

Korman’s aforementioned anthology opened with a section that included the few women poets known to him from the earlier periods of Yiddish literature, thereby creating a sense of traditional depth in women’s poetry in Yiddish that is problematic in view of the fact that modern Yiddish women writers did not make much use of the meager corpus of Old Yiddish literature written by women.

The outstanding embodiment of these aspects of modern women’s poetry in Yiddish was Miryam Ulinover, whose book of poems bore the outspoken title Der bobes oytser (My grandmother’s treasure; Warsaw, 1922). Ulinover also planned to publish an additional book of poetry entitled Shabes (SabbathShabbat), but her plans never came to fruition. Her work is situated at that rare juncture between women’s poetry in Yiddish and the world of Orthodoxy seeking its way into the realm of belles lettres.

Poetic Rejection of Jewish Femininity and Womanhood

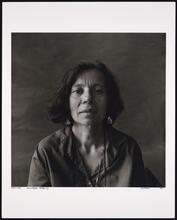

Most of the major women poets in Yiddish, however, advocated a different spiritual stance: There were those who bitterly contested the traditional Jewish world and the status of women within it, such as Kadya Molodowsky in her series of poems entitled “Froyenlider” in her first book, Khezhvndike nekht (Nights of Heshvan, 1927). Others sought to create a poetic persona that challenged conventional ideas. Some of the outstanding works of Celia Dropkin aimed to counter the accepted notion that women’s poetry in Yiddish must express a state of submissive womanhood. The collection of poems by Anna Margolin, Lider (1929), opens with a poem in which the speaker declares that he/she is a non-Jewish man, a pagan, hedonist and homosexual, thereby defying the expectation that women’s poetry in Yiddish should have a distinctive Jewish and feminine character. Margolin also violated the convention that women poets should primarily emphasize their feminine family background, which was characteristic of the world of Jewish culture; in several of her poems, the speaker implicitly negates accepted gender and cultural divisions.

The poetry of Anna Margolin, almost all of which is collected in her only volume of poetry, contains both confessional poems in the first person and the subtle shaping of a personal drama, both a pronounced empathy toward the characters in her poetic world and a distanced, ostensibly dispassionate, portrayal of them. The central characters in several of her poems wear a kind of mask, intended to conceal their inner essence and endow them with a foreign, even exotic, quality. Woman as an enigmatic icon that possesses the power of attraction is a central presence in her poems. In this way too, Margolin breaks with the convention that women’s poetry is supposed to be a tender, intimate discourse.

Contemporary Yiddish criticism indeed fostered the expectation that women’s poetry in Yiddish should serve, first and foremost, as an expression of the supposed “uniqueness” of the feminine experience, in which prominence would be given to eros and love. These implicit expectations were bolstered by the fact that the Yiddish literary establishment—namely, the editors of periodicals and literary critics—was comprised almost entirely of males. This feature of modern Yiddish culture is also apparent in the volumes of poetry published by the women poets; thus, for example, Miriam Ulinover’s book opens with an introduction by David Frischmann, while Itzik Manger wrote the introduction to the first book by Rajzel Zychlinski (1936), in which he writes that “the mother and child are the central figures in her genuinely feminine poetry.” The literary critics tended to compare the women poets with one another and it was only on very rare occasions that they placed the work of a Yiddish woman poet within the context of male writers. Several of the women poets in fact expressed their feeling that this was tantamount to establishing a literary “ghetto”—an approach against which they rebelled.

Thematic Evolution into Epic Narrative Poetry

The above list of women poets in Yiddish, which includes only the best known or most significant among them, is intended to illustrate the scope and diversity of the entire corpus. Obviously, their oeuvre cannot be circumscribed by rigid definitions, but there are certain common elements shared by most of the works. A recurring form in women’s poetry in Yiddish was the short lyric poem presenting an intimate confession centered on the inner world of the speaker and the manifest subjectivity with which she perceives external reality, in particular its immediate, sensory dimensions.

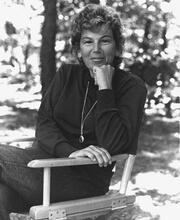

However, a number of women poets also wrote long epic narrative poems; the most prominent among these was Kadya Molodowsky. As early as her first book, she preferred the genre of the long poetic sequence with a loose connection between its components. Later she published the poem “Freydke” (1935), which presents—in a terse language replete with irony—a portrait of the world of Jewish workers drifting between Warsaw and Paris. In its atmosphere the poem is consistent with the poet’s radical ideology at this time and it ranks among the striking examples of the broadening of the thematic range of women’s poetry in Yiddish. In Molodowsky’s case, it should be noted that this entailed relegating to the background the personal world of women that formed the core of her first book. The connection between a bitter, detached epic tone and lyric empathy also marks the first book she published in the United States, In land fun mayn gebeyn (In the country of my bones, 1937), the individual poems of which create a tenuous chronological/biographical continuum that opens in Europe and concludes in the New Country. The desire to combine a lyric tone with narrative elements was successfully realized in that body of work which earned Molodowsky her greatest fame—her children’s poetry, written primarily in the period when the poet was living in Warsaw and working as a teacher of Yiddish in secular schools. These poems also won great acclaim in their Hebrew translation.

The thematic evolution that characterized Molodowsky’s work also marked that of other women writers of poetry in Yiddish, those who began to write in Poland in the 1920s and 1930s and enjoyed long creative careers, either because they left their homeland before the Holocaust (like Rikudah Potash, who immigrated to pre-state Palestine in 1934) or spent the war years in the Soviet Union (Rokhl Korn and Rajzel Zychlinski). For the most part, there is no discernible common thread linking these women writers. The early writings of Rokhl Korn bear the imprint of rural life and an unmediated connection with nature, which is portrayed as essentially positive but is accompanied by elements of violence, destruction and madness. By contrast, the first book of Rikudah Potash, Vint oyf klavishn (The Wind on the Piano Keys, 1934), stresses alienated, cosmopolitan urban existence, while the poems devoted to the landscapes of Poland are accorded only secondary importance. Following her immigration to Palestine, Potash’s poems underwent an interesting shift: she began to focus on ancient Canaanite motifs, which were a novelty in Yiddish poetry.

These changes are indicative of the thematic diversity that characterizes women’s poetry in Yiddish, which refuses to be shackled by binding definitions of any sort. Nevertheless, one can say that the tendency to limit itself to the private world of the (female) narrator, which typified the genre from its inception, resulted in a prosaic tone and a search for the exact poetic expression, even if it at times lacked color and the richness of cultural allusions.

Legacy of Yiddish Women’s Poetry on Yiddish Culture

However, in the best of women’s Yiddish poetry these qualities increased the propensity for startling, original, enigmatic imagery and distanced it from the use of trite, hackneyed idioms. Rajzel Zychlinski’s early works fashioned a world that was both limited and focused—that was cut off, in most instances, from any known historical or social framework, thus creating an implied sense of marginality. In her later poems, some of which were written in the urban setting of New York, this isolation is stressed to the point of placing the poet in a constant state of spiritual exile. The poems of Dvoyre Fogel, who wrote in the 1920s and 1930s and perished in the Holocaust, make frequent use of terms from the realms of painting, sculpture, engineering and architecture to create a world in which heightened visual awareness is intended to reinforce the sense of alienation and the escape to a false, melodramatic existence. The predominance of urban scenes in her writing (which includes numerous poems set in Paris) gives it an aura of cosmopolitan estrangement far removed from the mood of intimate domesticity.

Malka Heifetz Tussman’s first book of poems (1949) challenged two of the prevailing assumptions regarding women’s poetry in Yiddish. Despite the prevalence of free verse in her work, as befits a woman poet who profoundly absorbed the features of contemporary American poetry, she also tried her hand at intricate traditional poetic forms such as triolets and the crown of sonnets. Her language also reveals a surprising swing between colloquial everyday language and rarer terms that create a baroque style. The scope of these stylistic options narrowed in her later works, but did not disappear altogether: Tranquil memorial poems appear alongside rare but conspicuous examples of intellectual contemplation filled with striking paradoxes.

A tendency toward incisive, paradoxical language is a major characteristic of the work of Rokhl Fishman, the only Yiddish woman poet of stature to be born in the United States, although her writing career is associated with her A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz life in Israel. Her biting, elliptical language presents alternating states of conflict and conciliation between the primal forces of nature and the poet. She is conscious of the anarchic urges and suppressed violence within her and breaks with convention out of a fundamental sense of emotional and intellectual rebellion. The major manifestation of this rebellion is her longing to fuse with nature in a process of frenzied dynamism that never achieves a harmonious resolution.

The heightened presence of the forces of nature in Fishman’s poetry also serves to demonstrate the “Israeliness” of her existence. This was the point of departure for virtually all the Yiddish women poets who made their home in Israel, although the unique aspects of their geographical and cultural setting became blurred over time. A stylized view of external reality serves as the wellspring of Rivka Basman’s poetic world. Her impressions are presented in her poetry after they undergo a process of abstraction and generalization, whose source is her will to discover emotional forces capable of withstanding the ravages of time.

The literary output of modern Yiddish women poets should be read against the background of all the possible implications of culture, ideology and gender as shown in their work. Then it will be possible to understand this crucial chapter of modern Yiddish culture in all its fascinating manifestations.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “A Question of Tradition: Women Poets in Yiddish.” In Handbook of American Jewish Literature, edited by Lewis Fried, 195–237. New York: 1988.

Idem. “Songs of Herself.” Studies in American Jewish Literature 9 (1990): 138–149.

Klepfisz, Irena. “Queens of Contradiction: A Feminist Introduction to Yiddish Women Writers.” In Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers, edited by Frieda Forman et al., 21–62. Toronto: 1995.

Margolin, Anna. Poems. With an introduction by Abraham Novershtern. Jerusalem: 1991.

Molodowsky, Kadya. Paper Bridges: Selected Poems. Translated, introduced and edited by Kathryn Hellerstein. Detroit: 1999.

Niger, Samuel. “Yiddish Literature and the Female Reader.” In Studies in the History of Yiddish Literature (Yiddish). New York: 1959 (abridged English translation in: Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing, edited by Judith R. Baskin. Detroit: 1994).

Pratt, Norma Fain. “Culture and Radical Politics: Yiddish Women Writers, 1890–1940.” American Jewish History 70 (1980): 68–90 (this article is also included in Judith R. Baskin’s book).

Sokoloff, Naomi B., Anne Lapidus Lerner, and Anita Norich, eds. Gender and Text in Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature. New York: 1992.