Yiddish Literature in the United States

Although the full history of women writing in Yiddish in the United States has yet to be written, these women produced a broad range of texts: passionate and erotic lyrical verse, social realist fiction, affecting descriptions of immigrant life, nostalgic paeans to their Eastern European homes, dirges to those murdered in the Holocaust. These writers were modernists and traditionalists, romantics and realists, prose writers and poets. They represent no single school or line of development, but rather the range of women’s voices contained in Yiddish literature. Interest in women and Yiddish literature can be graced from the early decades of the twentieth century, and in recent decades there has been a turn to translating short stories and novels by women writing in American.

Transgression in Yiddish Women’s Writings

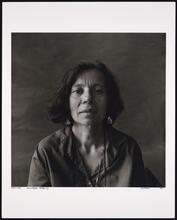

Rosa Lebensboim, known as Anna Margolin in 1903. Critics claim she authored the finest Yiddish poetry of the early twentieth century.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Ikh bin geven a mol a yingling” [I was once a lad] begins a Yiddish poem of the same name. Transgression—the sense of identity as permeable and unfixed—is announced in this line written by Anna Margolin, one of the few American women noted for writing in Yiddish. Yingling is not a word in Yiddish. It is a combination of yingl [boy] and yung [young], with an opaque suffix more familiar in English than Yiddish. In a language whose nouns are gendered, yingl may be either masculine or neuter (just as meydl—girl—is feminine or neuter), signaling at the outset of this poem the problem of claiming any stable rules or essential characteristics governing gender. However, the poem is not only linguistically transgressive. It invokes sexual transgressions as well, suggesting both homosexual and incestuous love and confusing the reader who sees the poet’s feminine name next to the word yingl. This poem, now known primarily in English translation (where yingling may be translated as youth, lad, boy, youngling), begins as though it were looking back, perhaps nostalgically, to the speaker’s youth. This youth could never have been experienced by the poet. Defying space, time, and sexuality, the speaker lays claim to several shifting identities in this twelve-line poem: male, Greek, Roman, Christian, at once a student of Socrates and a libertine. But never a woman or a Jew.

Recent considerations of Yiddish women’s texts privilege Margolin’s iconoclastic voice, seeing in it the tone and role women have assumed in the Yiddish literary tradition. Margolin is an ideal representative of such a voice: the peripatetic divorcée who left her infant son in the custody of his father, took lovers (including the poet Reuben Iceland), wrote under various pseudonyms (her real name was Rosa Lebensboim), wrote prose and essays as well as poetry, was known as an intellectual aggressive woman, and in later years, was a recluse reported to be too despondent to emerge from her apartment.

It is an exaggeration to claim transgression as the identifying characteristic of Yiddish literature by women, but it is an understandable exaggeration that seeks to redress the equally exaggerated, conventional claims that women have been the conservative force in Yiddish life and letters, the mothers holding home and tradition intact even when they have worked outside the home or have been involved in radical politics. Like other Jewish women in America, Yiddish writers have often been understood in terms of these mythic representations. They have been regarded as women who have had to overcome various hardships (poverty, child-rearing responsibilities, immigration) that impeded their writing, or as lonely women unable to find fulfillment in love or family, with neither a room of their own nor even a corner of the kitchen table on which to write.

The Breadth of Yiddish Women’s Writing

Writers of a broad range of texts—passionate and erotic lyrical verse, social realist fiction, affecting descriptions of immigrant life, nostalgic paeans to their Eastern European homes, dirges to those murdered in the Holocaust—these women are more accurately understood as modernists and traditionalists, romantics and realists, prose writers and poets. They represent, in short, no single school or line of development but rather the range of women’s voices contained in Yiddish literature.

The history of women writing Yiddish in the United States has yet to be written. It could be organized chronologically, thematically, or generically. A more controversial and more provocative approach would consider the status of Yiddish in Jewish cultural life and the extent to which Yiddish, the mame-loshn [mother tongue], has been feminized and domesticated. Scholars have launched this work, and it is now possible to list perhaps a hundred women who published prose and poetry in the United States in the last hundred years. Still, the prominent story is one of absence and the lack of basic biographical or bibliographical information about writers—even of the very names of women whose works are yet to be uncovered in the pages of scores of journals and newspapers, or who never found their way into print at all. Some of this is particular to the situation of women in Yiddish letters, but much of it is a reflection of the state of Yiddish literature in America more generally.

Literary History

The women who immigrated to the United States before 1924 (when changes in immigration laws made it harder to enter the country)—including such major writers as Celia Dropkin, Miriam Karpilove, Malke Lee, Anna Margolin, Anna Rapaport, Yente Serdatzky, Fradel Shtok, Malka Heifetz Tussman, Rashelle Veprinski, Hinde Zaretsky—did not conceive of themselves as a literary group. Most immigrant women were educated in Eastern Europe, receiving for the most part a better secular education but a less complete religious education than their brothers. Many became radicals and also began writing in Eastern Europe. If they are known today, it is largely through the efforts of English translators.

An outgrowth of the Haskalah [Jewish Enlightenment], modern secular Yiddish literature began in the mid-nineteenth century, spreading to all the corners of the world to which Eastern European Jews emigrated in the next hundred years. Among its early practitioners there are few well-known names of women, although women had certainly written Yiddish texts since the medieval period. Yiddish literary production in the United States is commonly understood to follow a generational pattern, beginning with the socially conscious poetry and prose of the “proletarian” or “sweatshop” writers of the 1880s–1900s. These primarily socialist writers were followed, in quick succession, by the rhymed and metered verses of Di yunge [The youth] who, in 1907, announced an “art for art’s sake” credo that elevated mood and tone over social relevance. In 1919, the Inzikhistn [Introspectivists] declared that free verse and social realities must be combined, that the poet’s craft required that he [sic] look into the self [in zikh] and thus present a truer image of the psyche and the world. The 1930s were marked by an expansion of socialist and communist journalism and the literature such politics inspired. The Holocaust, the Hitler-Stalin Pact, and the destruction of Eastern European Jewish life led to a more elegiac literature of consolation and mourning. More recent interest in Yiddish has resulted in the emergence of some new writers born in the United States, including women, and Haredim [ultra-Orthodox].

There are several problems with this chronological paradigm, not least the observation that literary epochs in Yiddish last about a decade, often overlap with one another, never correspond to the literary career of any writer, and rarely refer to more than a handful of writers at any period. Moreover, female writers seldom make their way into this schematic account except as the wives or sisters of male writers. Any sense of what constitutes the Yiddish literary canon is contested, but there has been increasing scholarly and popular attention to translating women and to including them in syllabi.

Yiddish Women’s Poetry

Critics have frequently noted that the greatest experiments and accomplishments in Yiddish literature in America took place in poetry rather than prose. Unlike their European and American contemporaries, women writing Yiddish have certainly been more prominent as poets. The reasons for this are social and generic, relying on the status of each genre in Jewish life as well as on the social conditions in which women found themselves. Poetry, some might argue, can sometimes be written despite hectic schedules that include the responsibilities of earning a livelihood and raising a family; the expansive form of the novel requires time and publishing resources rarely available to women. It is, however, difficult to imagine any poet making such an argument. A related explanation has been that, despite their crucial economic roles, Jewish women did not have the kind of grounding in an expansive and cohesive social world that storytelling demands. Religious life may have played a less central role in modern America than in nineteenth-century Eastern Europe, but neither as Jews nor as Americans were women and men similarly rooted. The status conferred by economic success in America, like the earlier status conferred by religious learning, one’s place in the synagogue, or ritual life among Jews, has always figured in masculine terms. The cultural effect of exclusion from these areas needs to be considered in any analysis of women’s literary production in Yiddish. So, too, must the Jewish storytelling tradition, associated as it is with religious learning, A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash and Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.aggadah. Men, in other words, could associate storytelling with tradition; they could tell their stories in the prayer house, between prayers, even as prayers. Women, for the most part, could not, and the different valence of their stories—told primarily in the kitchen, the parlor, or on the front stoop—no doubt affects the way they might have regarded stories and poems.

Yiddish as “Feminine”

Whatever the genre, the status of Yiddish as a literary medium also influenced women’s creative endeavors and the possibilities for publication. In its ongoing struggle for respectability, the mame loshn has had to distinguish itself from the feminized and the matrilineal. This is not to say that Yiddish was ever a “woman’s language,” but rather that it was seen in the context of both Hebrew with its patrilinear religious authority and also as an indigenous national language that carried secular authority. Yiddish was increasingly figured as the language of home in the modern, post- Haskalah period and especially in America. “To be a Jew in the home and a human being in the street,” as the Haskalah enjoined, meant confining the distinctive customs, appearance, and language of the Jew to the home, while appearing and sounding like everyone else in public.

Once Yiddish is identified with the maternal, the familiar, nurturing home, it also becomes, like that home, the place from which one sets forth into the mature world. Even when it was still the language of the Jewish masses, its use was often taken as a sign of their ignorance. Religious texts (the most famous example is the early-seventeenth-century Tsenerene [Hebrew name: ze’enah u-re’enah]) in Yiddish carried subtitles explaining that they were designed for women or ignorant men; Enlightenment writers turned to Yiddish because too few could read their Hebrew texts; in America, Yiddish could be seen as a necessary tool en route to English and acculturation (as suggested by Abraham Cahan and the most important Yiddish daily, the Forverts). Samuel Niger published an often-cited essay in 1913 (“Di Yidishe Literatur un di Lezerin” [Yiddish literature and the female reader]) in which he asserted the significant role of women in Yiddish letters as readers and writers, contrasting it with the role Hebrew assumed for male readers. It was difficult to disassociate Yiddish letters from these disparaging feminized images. Men writing in Yiddish might claim some distance from them, as Sholem Aleichem did when he established a patrilineal Yiddish literary genealogy that began with Mendele Moykher Sforim, whom he called der zeyde [grandfather]. Women could, it seems, primarily serve as a reminder of the limitations associated with Yiddish.

Interest in Yiddish Women Writers

In light of these concerns, the sheer numbers of female authors and their texts should perhaps surprise us more than the dearth of information about them. Interest in women and Yiddish literature, while limited in scope, can be traced from the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1917, M. Bassin’s 500 Yor Yidishe Poezye [Five hundred years of Yiddish poetry] anthologized ninety-five modern poets, the majority of them Americans. His volume included only eight women. In 1928, Ezra Korman’s Yidishe Dikhterins [Yiddish women poets] included the work of seventy poets. This was less than a quarter of the number included in Reyzen’s definitive Leksikon fun der Yidisher Literatur (1928), but Korman’s book was noteworthy both because it was published in the United States and because it focused exclusively on women’s poetry. It also entered into a series of debates about women in Yiddish that were sometimes witty, sometimes vituperative.

Several of the exchanges that represent this debate took place in the pages of the Warsaw journal Literarishe Bleter. In 1927, Melekh Ravitsh published an article whose critical stance can be discerned in its title: “Meydlekh, Froyen, Vayber—Yidishe Dikhterins” [Girls, Women, Ladies—Yiddish Poetesses]. Ravitsh claimed that what could be found in women’s poetry was hysteria, an excess of moralizing, and a lack of energy or new ideas, and that there were no worthy poets among women and there never would be. He was taken to task by two young women, both of whom were Yiddish teachers and were to become among the most noteworthy of the modernist poets in America: Kadya Molodowsky and Malka Heifetz Tussman. The combined presence of Ravitch, the most itinerant of Yiddish writers, Molodowsky, living at the time in Warsaw, and Tussman, then writing from her home in Milwaukee, attests to the international character of Yiddish literature at this time. Writers in America cannot be neatly separated from their peers in Europe since the lines of communication, publication, debate, and migration remained open (at least until the Second World War) in both directions with writers on both continents reading and writing in the same journals.

These debates about the role of women in Yiddish are perhaps best epitomized in two essays, one written in 1915 by the renowned (male) poet Aaron Glants, the other written twenty years later by Kadya Molodowsky, the equally renowned (female) poet. Glants, lamenting the absence of a female presence in Yiddish literature, called for a new era. He claimed that Yiddish literature would stagnate if only men’s voices were heard in it. Based partly on essentialist notions of masculinity and femininity—the latter, predictably, seen as more intuitive and emotive—Glants insisted that the inclusion of women was necessary if Yiddish was to live up to its full cultural potential.

When Kadya Molodowsky turned to the question of women poets, she echoed parts of her earlier argument with Ravitsh and wrote a sarcastic dismissal of the very concept of “women poetesses.” Molodowsky, who had arrived in the United States in 1935, was an acclaimed teacher and writer (of poetry, prose, drama, children’s stories). She was to go on to serve as the editor of Svive (1943–1944, 1960–1974), an important literary-cultural journal. No female cultural figure could boast of such a position, although some had written regular columns in other journals. In 1936, responding to a number of articles and cultural events honoring women writers, she dismissed such events as condescending, another way of marginalizing the work of poets and women. The very concept of the “female poetess” showed a kind of intellectual laziness on the part of critics, an inability to grapple with the real differences among writers, a way of essentializing women’s voices and relegating them to the status of “tsarte, oftmol ekzotishe blumen in literarishn gortn” [dainty, often exotic flowers in the literary garden]. Without referring to her own poetry, but reflecting its themes and tones, Molodowsky dismissed the notion that women were more sensitive than men or more likely to write love poetry. Such beliefs recalled the function of the women’s gallery in synagogues through which women might peer at the public roles men assumed but from which their voices were never to emerge. For all their differences, Glants and Molodowsky were arguing for the same thing: an honorable position for women in the Yiddish literary canon. Increasingly frightening events in Europe—events culminating in the Stalinist purges and the Holocaust—soon overshadowed questions about the role of women in Yiddish.

It would take decades before critics returned to these questions. In 1966, Shmuel Rozhansky published Di Froy in der Yidisher Poezye [The woman in Yiddish poetry] as volume 29 of his Musterverk fun der Yidisher Literatur, a monumental project of canon formation intended to run to one hundred volumes containing representative works of Yiddish literature. Previous volumes had focused on individual authors or a group of two or three, but this one included 136 poets of whom about one-third were women. In 1973, Ber Grin published a series of articles presenting short biographical and bibliographical information about women poets in various countries. Harking back to Korman’s title (which was his own as well) and the significance of that volume, Grin went on to list the names of twenty-four women who constituted a new generation of American Yiddish women writers. He referred to yidishe dikhterins with none of the irony or self-consciousness that Molodowsky’s 1936 essay or the earlier essays by her and Tussman might have encouraged. Grin divided his entries by country, including the biographies of twenty-seven women under the heading “American Yiddish poetesses.”

More recently, however, the story of women in Yiddish literature, like that of Yiddish literature in general, must be understood primarily as one of translation and analytical essays. Still, as Kathryn Hellerstein has noted, few women appear in English anthologies: one out of fourteen writers in Betsky’s Onions, Cucumbers and Plums (1958); twelve out of 141 in Leftwich’s The Golden Peacock (1961); three out of fifty-seven in Lucy Dawidowicz’s The Golden Tradition (1967); one out of eighty-two in Leftwich’s Great Yiddish Writers of the Twentieth Century (1969); six out of fifty-eight in Irving Howe and Eliezer Greenberg’s A Treasury of Yiddish Poetry (1969); one out of seven in Benjamin Harshav’s American Yiddish Poetry (1986); five out of thirty-nine in Howe, [Ruth] Wisse, and Chone Shmeruk’s The Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse (1987).

Hellerstein’s A Question of Tradition (2014), on the other hand, is entirely devoted to women who wrote Yiddish poetry. There are also single-author collections of poetry in translation, including works by Kadya Molodovsky, Celia Dropkin, and Malka Heifetz-Tussman. There has also been a turn to translating short stories and novels by women writing in America. Translations of novels—a genre women were once thought (incorrectly) not to have written—began appearing at the turn of the twenty-first century, including Canadian writer Chava Rosenfarb’s works, a novel by Molodovsky (A Jewish Refugee in New York, 2019), and another by the prolific writer Miriam Karpilove (Diary of a Lonely Girl, 2019). The twenty-first century also saw a growing attention to translating short stories by women, including the works of Rosenfarb, Molodovsky, Yenta Mash, and Blume Lempel, as well as multi-author collections (Beautiful as the Moon, Radiant as the Stars (2003); Arguing With the Storm (2007); The Exile Book of Yiddish Women Writers (2013); Pakn Treger’s Collection of Newly Translated Yiddish Works by Women Writers (2017). Earlier collections include The Tribe of Dina (1986) and Found Treasures (1994).

The significance of the poetry and prose produced by women in Yiddish cannot be understood in terms of these counting exercises, revealing though they may be. Such assessments will emerge only from the ongoing work of translation, criticism, bibliography and, above all, reading.

Glants, A. “Kultur un di Froy” [Culture and women]. Di Fraye Arbeter Shtime (October 30, 1915): 4–5.

Grin, Ber. “Yidishe Dikhterins” [Yiddish poetesses]. Yidishe Kultur (December 1973, January 1974, March 1974, April–May 1974).

Hellerstein, Kathryn. A Question of Tradition: Women Poets in Yiddish, 1586-1987. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “Canon and Gender: Women Poets in Two Modern Yiddish Anthologies.” Shofar 9, no. 4 (Summer 1994): 9–23.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “In Exile in the Mother Tongue: Yiddish and the Woman Poet” In Borders, Boundaries, and Frames, edited by Mae G. Henderson. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Klepfisz, Irena. “Queens of Contradiction: A Feminist Introduction to Yiddish Women Writers.” In Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers, edited by Frieda Forman, Ethel Raicus, Sarah Silberstein Swartz, and Margie Wolfe, 21-62. Toronto: Second Story Press, 1994.

Korman, Ezra. Yidishe dikhterins. Chicago: L.M. Stein, 1928.

Molodowsky, Kadya. “Meydlekh, Froyen, Vayber, un ... Nevue” [Girls, women, wives, and prophecy]. Literarishe Bleter (June 3, 1927), and “A Por Verter vegn Froyen Dikhterins” [A few words about women poets]. Signal 6 (June 1936): 23.

Niger, Samuel “Di Yidishe Literatur un di Lezerin” [Yiddish literature and the female reader]. Der Pinkes (1913).

Norich, Anita. “Jewish Literatures and Feminist Criticism: An Introduction to Gender and Text.” In Gender and Text in Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature, edited by Naomi Sokoloff, Anne Lapidus Lerner, and Anita Norich. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1992.

Pratt, Norma Fain. “Culture and Radical Politics: Yiddish Women Writers, 1890–1940.” American Jewish History 70 (September 1980): 68-91.

Ravitsh, Melekh. “Meydlekh, Froyen, Vayber—Yidishe Dikhterins” [Girls, women, wives—Yiddish poetesses]. Literarishe Bleter (May 27, 1927).

Rozhansky, Shmuel, ed. Di Froy in der Yidisher Poezye [The woman in Yiddish poetry]. Buenos Aires: Ateneo Literario en el IWO, 1966.

Tussman, Malka Heifetz. “An Entfer Melekh Ravitshn af ‘Meydlekh, Froyen, Vayber—Yidishe Dikhterins’” [A response to Melekh Ravitsh]. Cited in Hellerstein, A Question of Tradition, 429.