Tamar 2

The story of the rape of Tamar, daughter of King David, by Amnon, her half-brother (2 Samuel 13) is told in the wake of the king’s sins of adultery and murder. When Tamar attends Amnon, who feigns illness, he seizes her and rapes her, and then banishes her from the room. The only woman whom we hear voicing resistance to rape, she is silenced in the end by her full brother, Absalom, and lives the rest of her life forlorn in his house. He then enacts vengeance against her rape, murdering Amnon and staging an insurrection against his father, the king. Throughout the account, David is strongly implicated in his daughter rape, passively indulgent of his sons, who mirror and amplify the sins of the father.

Tamar, daughter of King David, is first introduced as the beautiful sister of Absalom (1 Samuel 13:1), the third son born to the king in Hebron; their mother Maacah was David’s third wife, daughter of King Talmai of Geshur (2 Samuel 3:3, 1 Chronicles 3:2). Triangulated between powerful men, Tamar is raped by her half-brother, Amnon, while her father, the king, inadvertently facilitates his daughter’s violation (2 Samuel 13:1-22). Absalom, her full-brother, silences her and later avenges her rape (13:23-38). Though she remains muted and desolate in her brother’s household for the rest of her life, never to marry or bear children, Tamar is the only woman whose voice is heard aloud in protest to rape in the Hebrew Bible.

A Prophecy of Doom

The story of Amnon and Tamar appears in the wake of David’s adultery with Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11). According to Nathan’s prophecy, calamity would rise up against David from within his own household as a consequence of his taking Bathsheba secretly and having Uriah, her husband, slain in battle: the sword would never depart from the kingdom and another man (or “neighbor”) would lie with his women in public (12:9-11). After the death of the unnamed infant son conceived in adultery, the princess Tamar is the next to be struck. While most interpretations surmise that Nathan’s curse refers to Absalom’s sexual conquest of David’s ten concubines on the roof (2 Samuel 16:21-22), the “neighbor” may allude to his own firstborn son, Amnon, who forcibly lies with his half-sister Tamar.

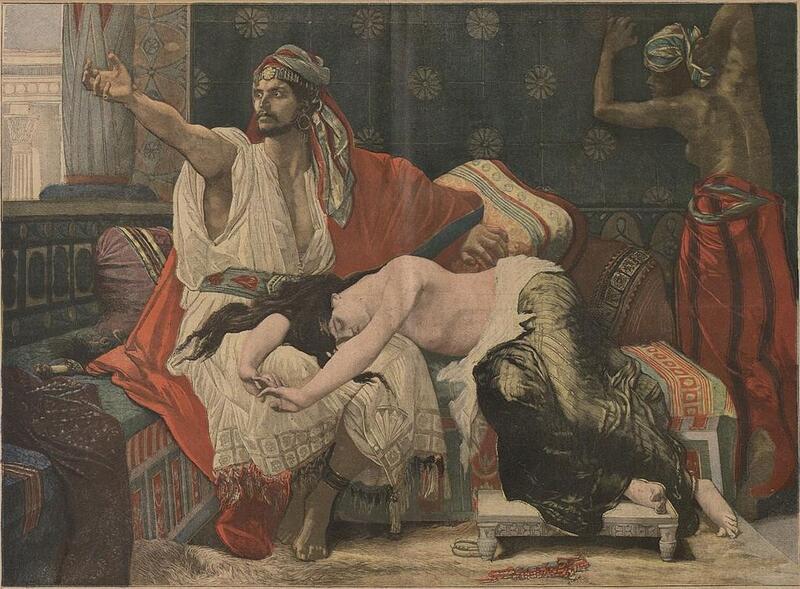

The Rape of Tamar

In all three rape narratives in the Hebrew Bible—the story of Dinah and Shechem (Genesis 34), the concubine of Gibeah (Judges 19), and Amnon and Tamar (2 Samuel 13)—the father is subtly implicated in his daughter’s violation because of his own prior actions. At the outset of this story, Amnon is “sick” with love for Tamar, because “she was a virgin, and it seemed impossible to Amnon to do anything to her” (v. 2). His “wise” or “crafty” friend and cousin Jonadab advises Amnon to feign illness and have the king send Tamar to his sickbed to prepare food in his presence, that he might “see it, and eat it from her hand” (v. 5). Unaware of the plot, David sends Tamar to attend to Amnon. Kneeling before him, she prepares heart-shaped cakes [lbb levivot] before him (vv. 6, 8). Amnon then sends all his servants out, forcibly takes hold of her, and pleads, “Come lie with me, my sister” (v. 11). Yet Tamar, unlike other victims of rape in the Hebrew Bible, is given voice in her resistance:

“No, my brother, do not force me; for such a thing is not done in Israel; do not do this outrage [nevelah]! As for me, where could I carry my shame? And as for you, you would be as one of the scoundrels [nevelim] in Israel. Now therefore, I beg you, speak to the king; for he will not withhold me from you" (2 Samuel 13:12-13).

In a subtle, eloquent play on words, Tamar warns Amnon that if he were to do this “outrage [nevelah]”—a term associated with the collective shame carried by the violated woman’s body (Genesis 34:7, Judges 19:23–24, 20:6, 10)—he would be like one of the “scoundrels [nevelim]” in Israel. Further, despite the incest taboo, Tamar suggests that the King would grant her to Amnon in marriage if he were to ask. Whether she would have been permissible to him as his half-sister is questionable, but at that point her argument seems to arise from sheer desperation. The king is inserted here as an alibi, a bid for time and for the pause of conscience in the violent passion play.

The Rape’s Aftermath

After Tamar is raped, Amnon is seized with hatred for her. “His loathing was even greater than the lust he had felt for her,” and he orders her out with two callous words, “Up, go!” (v. 15). Despite her request not to shame her further in this way (v. 16), he commands his servant to send “this one” out (v. 17). As an object of loathing, the woman is reduced to the demonstrative pronoun “this”; when she ceases to satisfy, she is cast away. In the narrative and in her own plea, Amnon’s banishment is worse than the sexual violation, for Tamar has little recourse as a victim of both rape and later revulsion by the king’s son. According to the law, the one who seduces or rapes a virgin out of wedlock must pay the bride-price and marry her (if the father approves), and he may never divorce her (Exodus 22:16-17, Deuteronomy 22:28-29). While incest may preclude this option, the prince’s loathing of his rape victim (and his father’s indulgence) seals her fate. Amnon has his servant banish Tamar from his chambers and lock the door behind her (v. 17).

In response, Tamar tears the long-sleeved cloak [ketonet passim] characteristic of the virgin daughters of the king (vv. 18-19). The rending of the cloak foreshadows the rent in the fabric of the kingdom. It also resonates with the garment worn by Joseph, also a ketonet passim, so incendiary to sibling rivalry (Genesis 37). Joseph, like Tamar, had been a victim of fraternal violence. He is “disappeared” by his brothers down into the “pit” of slavery in Egypt, while she is “disappeared,” rendered a persona non grata as a consequence of shame.

Tamar’s signs of mourning—ashes on her head, torn garment, and wailing (v. 19)—demonstrate publicly that she has been violated. But Absalom, her full brother, orders her to be silent, suggesting that nothing could be done to restore her honor, and Tamar lives out the rest of her life forlorn in her brother’s house (v. 20). The king, on the other hand, when he hears of the rape, does not punish Amnon, “because he loved him, for he was his firstborn” (2 Samuel 13:21 NRSV, based on the Septuagint, an alternative to the Masoretic text. The father is deeply implicated in both the violation of his daughter and the lack of consequence for his rapist son. The incestuous rape results in fratricide (13:23-38) when, two years later, Absalom has Amnon killed in the context of a sheep-shearing feast to which all the king’s sons are invited. This murder leads to Absalom’s exile and David’s opprobrium, which devolve into insurrection and civil war (chapters 15-18) and ultimately the unraveling of the king’s entire household in fulfillment of Nathan’s prophesy. Tamar is thus both a full-fledged character who speaks and arouses the readers’ sympathies and a symbolic figure, a victim of divine retribution exacted upon her father.

While Absalom’s suppression of his sister’s cries may enable him to plot revenge, it denies her the right to testify to her own violation and reinforces her shame and banishment from the social order. Though she remains desolate in her brother’s household, Tamar is the only woman who voices resistance to sexual violation, and so continues to present a powerful example of protest for women today. She is further granted an after-life, in that Absalom names his beautiful daughter Tamar, presumably after his sister (2 Samuel 14:27).

Bar Efrat, Shimon. Narrative Art in the Bible. Sheffield: Almond Press, 1989.

Fokkelman, Jan. King David, vol. 1 of Narrative Art and Poetry in the Books of Samuel. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1981.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Reading the Women of the Bible. New York: Schocken, 2002.

Polzin, Robert. David and the Deuteronomist. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Scholz, Susanne. Sacred Witness: Rape in the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010.

Trible, Phyllis. Texts of Terror: Literary Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1994.

Van Dijk-Hemmes, Fokkelien. “Tamar and the Limits of Patriarchy: Between Rape and Seduction (2 Samuel 13 and Genesis 38).” In The Double Voice of Her Desire. Leiden: Brill, 2005.